Modern Man is Afraid of Dandyism. Except for a few…

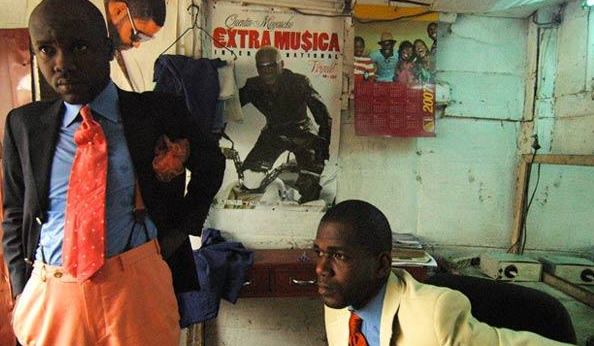

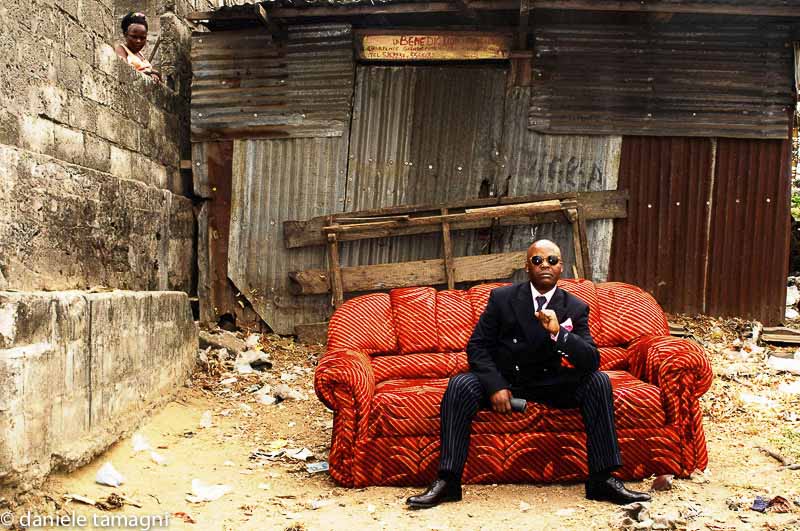

When you think of silk handkerchiefs, pink corduroys, tweed and double-breasted tailoring, would you associate such a style of dress with some of the poorest slums of Africa?

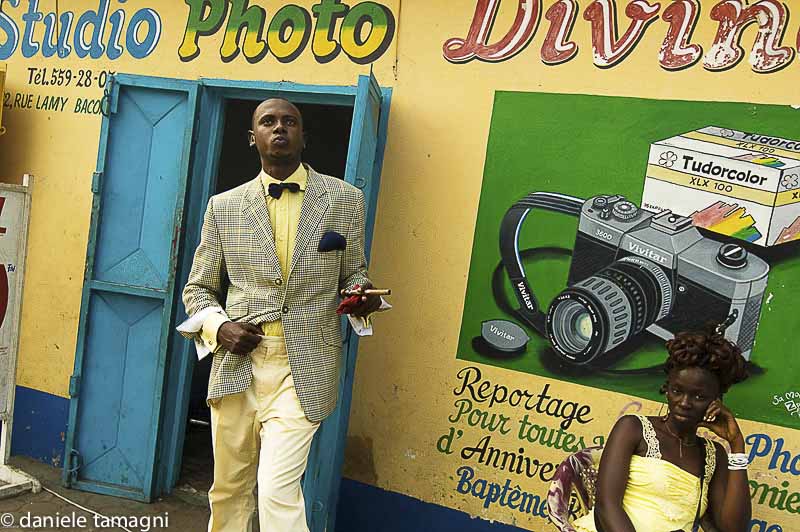

What you’re looking at is the phenomenon of Sapeurs, a subculture of extraordinarily dressed dandies from the Congo. In the midst of their war-torn slums, these men dress in tailored suits, elegantly smoke on their pipes and stroll the impoverished streets in immaculate footwear.

Dandyism or sapologie in this case, is not a fashion trend. In some of the farthest corners of the earth where true dandyism exists, it serves as something closer to a religion; a code of living.

The Story of Sapeurism

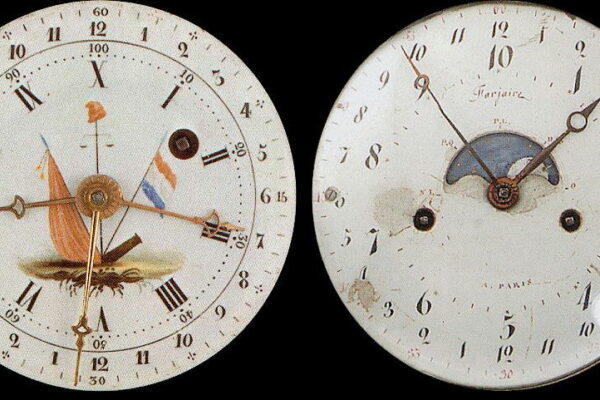

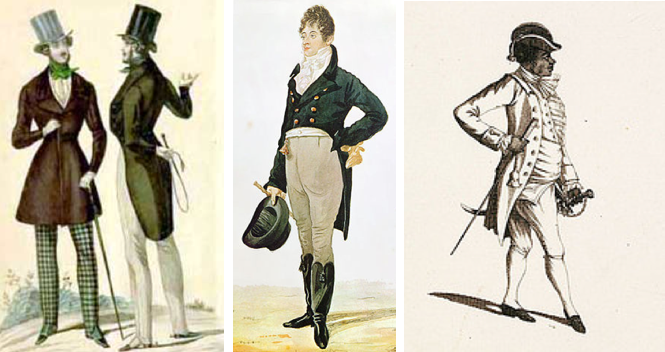

Records of African dandy men go back as far as the 18th century when enslaved Africans were given extravagant and elegant costumes by their European masters to effectively ‘fit in’ with their luxurious surroundings. By the time the slave trade was abolished, liberated Africans had already begun to create their own unique dandy style, in some cases, doing it better than the Europeans had ever done it. A dandy, who was self-made, often strove to imitate an aristocratic lifestyle despite coming from a middle-class background.

The little-known subculture of the Congo Sapeurs comes from la SAPE, short for Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes, or the Society of Tastemakers and Elegant People. The first ‘icon’ or ‘Grand Sapeur’ was André Matsoua, an influential Congolese religious and political figure who in 1922, returned from Paris, to the amazement of his traditional African countrymen, dressed entirely in elegant French clothing.

SAPE as the Congolese (and now you) know it, was not officially born until an emerging pop star in the late 1960s sparked somewhat of a style revolution. Papa Wemba, known as La Pape* de la Sape (pope of Sape) had an incurable fever for French fashion after multiple trips to Paris for his gigs. Under the strict Mobutu regime, freshly liberated from Belgium, any association with Western culture in Congo was severely frowned upon. Papa Wemba’s defiance became a symbolic gesture in the midst of economic deprivation and political dictatorship. Papa Wemba even established his own village that upheld a set of moral codes with emphasis on high standards of personal cleanliness, hygiene and smart dress among Congolese youths regardless of societal differences.

The Code of Sapologie

A sapeur must have sartorial know-how. Socks should be a certain height, a maximum of three colors can be used in one outfit and an attention to detail is required, such as leaving the bottom cuff button of a suit jacket undone (tell-tale difference between an off-the-rack suit and a tailored one is buttonholes that you can actually undo). They consider their style as an art form– the art of being a gentleman. Of course many books will tell you being a gentleman is not just about being a sharp dresser, it is also about impeccable manners.

Despite most having witnessed first-hand the brutality and horror of three civil wars, a sapeur is known as a non-violent person, respectful and considerate towards others. One of their mottos include, “Let’s drop the weapons, let us work and dress elegantly”. Most are Catholic and attend church regularly. A drug habit does not an elegant lifestyle make; sapeurs observe a drug-free, generally conservative existence.

What’s Wrong With this Picture?

I know you’ve been thinking it– here comes the reality. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the average annual income is about US$100, among the lowest in the world, according to the World Bank. In case you were wondering whether there might be a very reasonably priced tailor living somewhere in the area, you should know that a sapeur is likely to spend as much on an imported Italian-made suit jacket as he is on a house in the Congo’s capital Kinshasa.

I read about one Congolese sapeur who worked eight months at his part-time job just to earn enough for a single outfit, one of 30 he owns, so he never has to be seen wearing the same outfit twice in one month. The reality of his situation is very inconsistent with the image he likes to project. He leaves his ex-girlfriend to support their 5-year-old son and still lives with his parents in a tiny room with a mattress.

Over twenty-five years after La Sape was born, the movement is morphing more and more into a craze for expensive French and Italian designer labels. Many of today’s younger followers of SAPE wear color-blinding outfits that costs upwards of $10,000 and attend weekly ‘throw downs’, competing to see who’s wearing the most expensive designer labels. They also happen to barely make a living out of the rubble that remains in their war-torn hometowns.

Before visas became difficult to get, some would travel to Europe to buy clothing to sell back home. Some rely on Congolese shoplifting gangs in Brussels and Paris to send them the latest designer suits, many have spent time in jail and some simply piece together outfits by borrowing. The Sapeurs dream of making it to Paris– what they see as the ‘promise land’ of haute ‘sapeurism’. Even Papa Wembe ended up in jail for attempting to smuggle two-hundred illegal immigrants into France, attempting to pass them off them as members of his band. Those that do make it to Paris mostly end up in the ghettos, far removed from their ‘Parisian dream’, washing dishes or in some extreme cases, selling themselves into male prostitution.

It would appear, never was there a more appropriate context for the expression, ‘fashion victim’. Older members of the SAPE have expressed regret for the example they have set for the younger generations, admitting ‘it was like a drug’.

But is it all that different from some of the extremities of our own fashion industry of the modern western world?

Long-live Sapeurism?