In the furthest corner of the Vincennes woods of Paris, lies the remains of what was once a public exhibition to promote French colonialism over 100 years ago and what we can only refer to today as the equivalent of a human zoo.

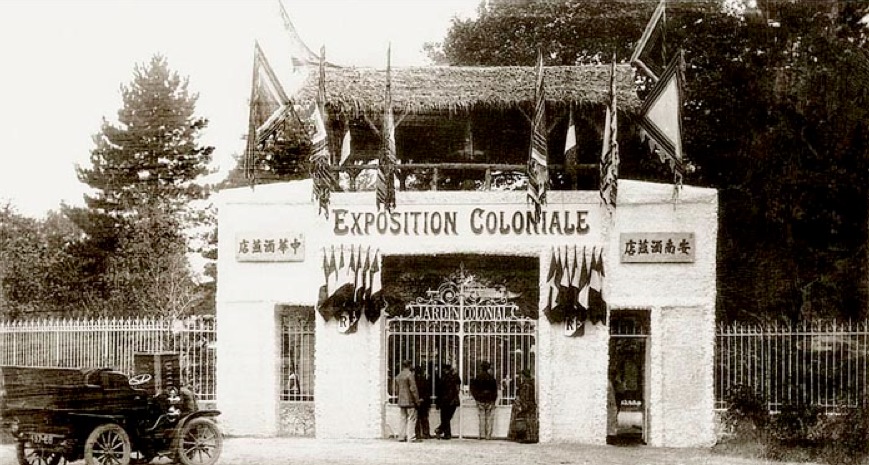

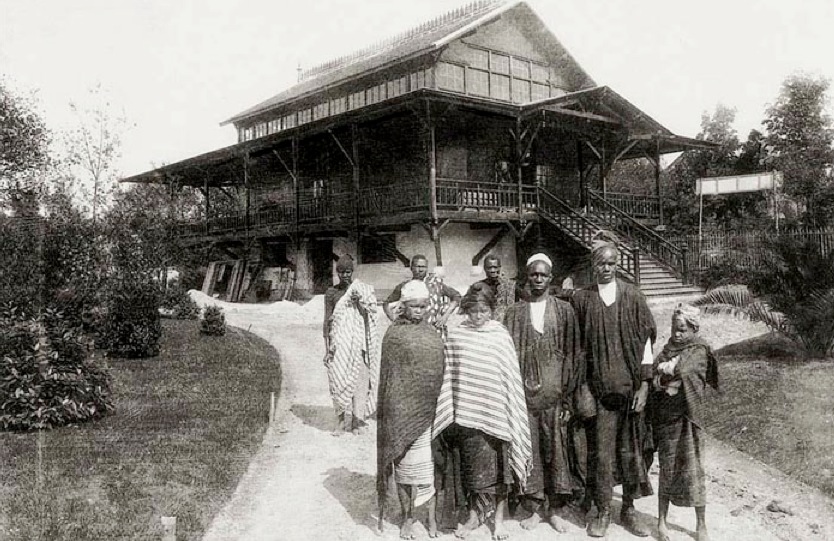

In 1907, six different villages were built in the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale, representing all the corners of the French colonial empire at the time– Madagascar, Indochine, Sudan, Congo, Tunisia and Morocco. The villages and their pavillions were built to recreate the life and culture as it was in their original habitats. This included mimicking the architecture, importing the agriculture and appallingly, inhabiting the replica houses with people, brought to Paris from the faraway territories.

The human inhabitants of the ‘exhibition’ were observed by over one million curious visitors from May until October 1907 when it ended. It it estimated that between 1870 up until the 1930s, more than one and a half a billion people visited various exhibits around the world featuring human inhabitants.

In 1906, this Congolese replica “factory” was built in Marseille as part of a colonial exposition. Congolese families were also brought over to work in the factory. In February 2004 its remains were burnt down.

Today, the Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale is treated as a stain on France’s history. Kept out of sight behind rusty padlocked gates for most of the 20th century, the buildings are abandoned and decaying, and the rare exotic plantations have long disappeared.

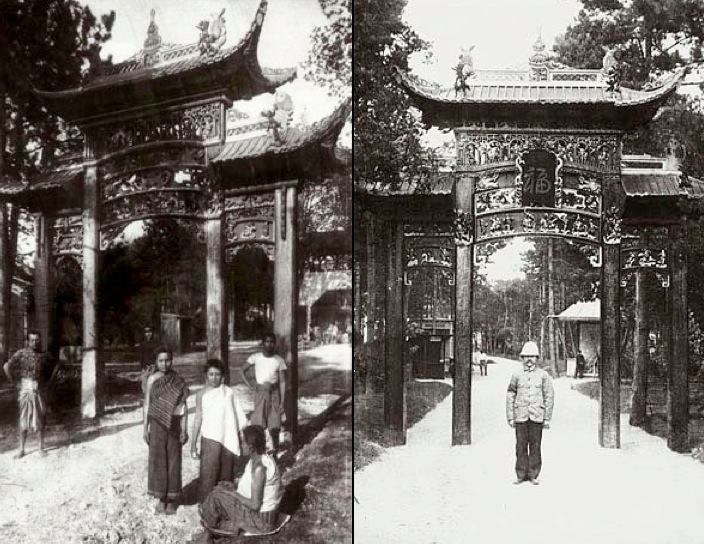

In 2006 the public was granted access to the gardens but few people actually visit at all. The entrance is marked by a 10 ft Asian inspired portico of rotting wood and faded red paint that stands like the ghost of a slain gatekeeper. Visitors can instantly feel a sense of anxiety upon entering and quickly develop an understanding that this is not a place that the French are proud of. A hundred years on and there’s still an eerie presence of ladies clutching sun parasols and men in bowler hats arriving, eager to see the show on the other side of this now crumbling colonnade.

Only some of the pathways remain clear of overtaking nature and they all lead to various vandalized monuments, condemned houses with danger signs and abandoned paraphernalia that you can’t make any sense of.

A doorway to one of the houses at the Indonesian pavillion

The Moroccan pavillion

I sneaked over a fence into this eerie structure hidden at the back of the park, a workshop where scientists and students came to study tropical wood brought back from the colonies.

More than thirty-five thousand men, women and children left their homelands during the high noon of Imperialist Europe and took part in ‘exotic spectacles’ held in major cities like Paris, London and Berlin. Entire families recruited from the colonies were placed in replicas of their villages, given mock traditional costumes and paid to put on a show for spectators. An opportunity to demonstrate the power of the West over its colonies, the expositions became a regular part of international trade fairs and encouraged a taste for exoticism and remote travel.

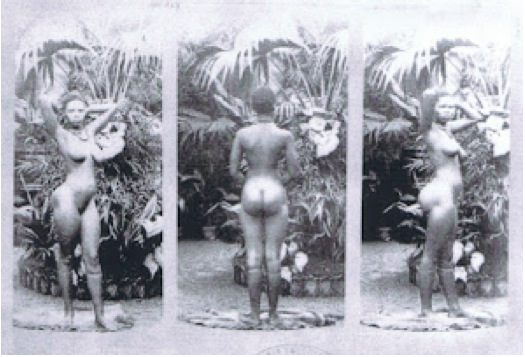

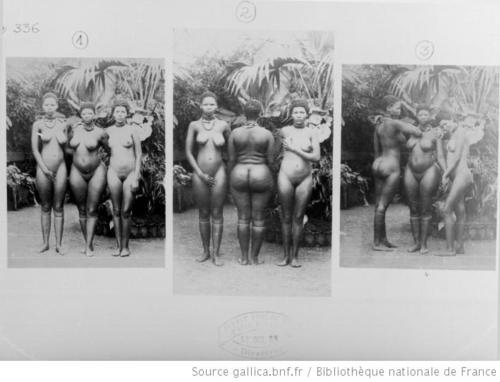

Europeans gawked at bare-breasted African women and were entertained by re-enactments of “primitive life” in the colonies. Here, anthropologists and researchers could observe whole villages of tribespeople and gather physical evidence for their theories on racial superiority.

The Tunisian pavilion.

While the villagers had come to Paris of their own free will and were paid to be on display, they were equally oppressed, exploited and degraded. The distinction between person and specimen was blurred. They were not guests here. They were nameless faces on the other side of a barrier.

When the Exposition Tropicale ended its four month run in October 1907, it is unknown how many of the participants returned home safely. Villagers were enticed by lecherous agents or even mislead by their own village chiefs into joining circus-like troupes that toured internationally. From Marseille to New York, their vulnerability in a capitalist world was exploited every step of the way.

Some would eventually find their way home after a few years, but others would never make it. If they didn’t fall victim to diseases unknown to them; smallpox, measles, tuberculosis; they would die of adversity in an alien world.

There are rumors that one building, the Indochine pavillion, will be refurbished to function as a small museum and research centre. It may be an intelligent solution to a touchy subject. If the French government destroyed the gardens, there would be accusations of trying to cover up the past. If they were fully restored, it might be construed as a commemoration to a France’s once very sinister use of power.

And so the garden remains, hauntingly beautiful; a neglected embarrassment.

Gardeners stopped coming a long time ago. Wild and verdant, mutations of untamed tropical plants plucked from their homelands are left to fester in a junkyard of French colonial history. They are the ghosts of this purgatory, waiting for a ticket home.

Address: Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale, 45 bis Avenue de la Belle Gabrielle, 75012 Paris. RER station: Nogent-sur-Marne

Sarah’s Story: A Colonial Showpiece

The primitiveness of putting the ‘primitive’ on display began during the modern period when explorers like Columbus and Vespucci lured natives back to Europe from their homelands. To prove the discovery of exotic lands, the natives were flaunted and paraded like trophies. But what began as curious awe deteriorated into an era of racial superiority and the invention of the savage.

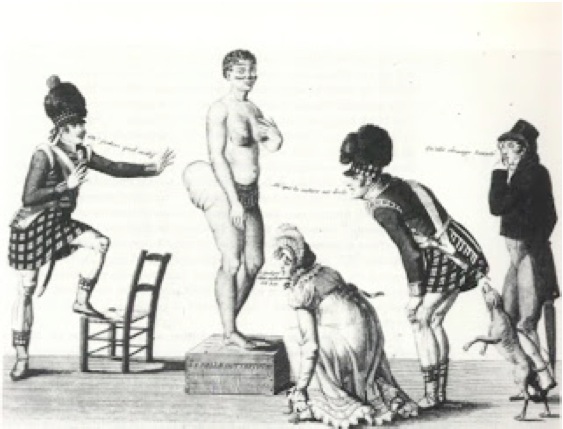

A 20 year-old girl from South Africa known as Sarah “Saartjie” Baartman would be emblematic of the dark era that gave rise to the popularity of human zoos. She was recruited by an exotic animal-dealer on location in Cape Town and traveled to London in 1810 to take part in an exhibition. The young woman went willingly under the pretense that she would find wealth and fame. Exhibitors were looking for certain qualities in their ‘exotic’ recruits that either coincided with the European beauty ideal or offered unexpected novelty. Sarah had a genetic characteristic known as steatopygia; a protuberant buttocks and elongated labia.

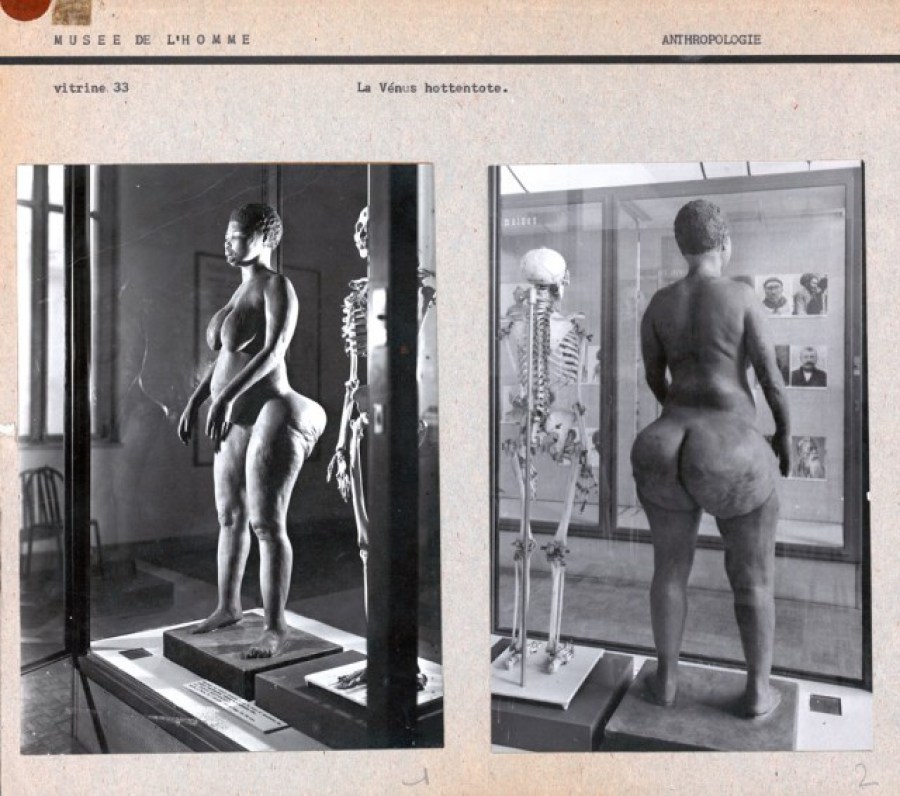

She found herself being exhibited in cages at sideshow attractions dressed in tight-fitting clothing that violated any cultural norms of decency at the time. A few years later she came to Paris where racial anthropologists poked and prodded and made their theories. Sarah eventually turned to prostitution to support herself and drank heavily. She had been in Europe for only four years.

When she died in poverty, Sarah’s skeleton, sexual organs and brain were put on display at the Museum of Mankind in Paris where they remained until 1974. In 2002, President Nelson Mandela formally requested the repatriation of her remains. Nearly two hundred years after she had stood on deck and watched her world disappear behind her, Sarah Baartman finally went home, where the air smelled of buchu and mint, and the veld called out her name.

Additional images via Les Expositions universelles de Paris, Invisible Paris, Shane Lynam and Olivier Aubert