This weekend I spent Friday night with le boyfriend doing what any normal girl likes to do: scoping out derelict buildings. We were having a drink on the Seine in the 13th arrondissement when he remembered there was an enormous old building in the neighborhood infamously occupied by squatters. Off we went.

And there it was, smack in the middle of a modernized area in Paris, surrounded by contemporary glass apartment blocks and shiny new developments; defiant and fantastic. Hard to reach places were covered in impressive graffiti, or more appropriately in this case, street art, and a large water tower soared above our heads.

As we circled the building looking for a way in, we noticed lights in windows were lit and someone was even hosting a little soiree in the leafy courtyard over the fence.

The next morning I had a Google.

The building is called Les Frigos, literally meaning ‘the fridges’ and it was once an ice, essentially a giant refrigerator– which explains the water tower. Nearly 100 years old and covering 43,000 square feet, it was formerly owned by the SNCF rail company. In the 1980s a number of artists began squatting in the abandoned factory and it quickly became synonymous with art and rebellious spirit amongst the neighboring residents living in the gleaming new apartments that surrounded the property. At the same time, authorities were working to expel the tenants. After many years of failing to vacate the vagabonds, the Paris city hall finally bought the building to ensure that the artists could stay and create.

Having won the right to freely occupy the building they had broken into years ago, the residents formed an organization under the adopted name of “Les Frigos“, and today over 200 artists work and live in this multi-story building. And members are quick to point out that despite appearances, they are not squatters.

Certain technicalities in French law however say differently…

“Once a squat gets renovated, the law stipulates that you are not allowed to use the place as living premises, just use it as work space,” says Julien de Casabianca, the founder of Le Laboratoire de Création (laboratoiredelacreation.org), another renovated squat that popped up on the posh rue St.-Honoré. “Of course, no one ever lives there officially, but the reality is often quite different. Squatting, legalized or not, is a lifestyle.” [NYT]

Although we weren’t able to find our way in on that Friday night, there are ways. Officially, the public cannot stroll in as it pleases but the ateliers and workshops hold regular events and open days and locals will assure you it’s usually fine to show up and ask a resident for a tour. (Just flash a wink and a smile).

The Parisian art scene toay is infamous for being an impossible one to break into as an artist. The residents of ‘Les Frigos’ may not have made it through the front door of the Louvre but over time they have become accepted as an important part of the cultural life of the 13th district. You could even say they’ve slipped into the art world through the back door.

And they’re not the only ones. It turns out art ‘squats’, legalized and yet-to-be-legalized have been popping up all over town for a while now.

Even more central is 59 Rivoli (59 rue de Rivoli) next to Pont Neuf, where over thirty artists occupy a grand Haussmann era building previously owned by the Credit Lyonnais bank. How did they get there? After moving in as squatters in 1999, a group of bohemian young artists began decorating the facade with their avant-garde art, causing a bit of a stir and attracting quite the crowd– locals and tourists alike.

Once again, it was the Paris city hall that stepped in and bought the building for 10 million euros, renovated it over three years and reopened it as a legitimate studio space for artists also known as the ‘Aftersquat’. With art being a billion dollar business, why not invest in some home-grown talent?

Following the example of 59 Rivoli, several more abandoned and squatted spaces were bought and renovated as legitimate workshops, complete with fancy websites and an even fancier following.

The city hall began striking deals with selected squatters allowing them to stay in residence for a rent prices as low as 1 euro per day on the condition that they continue to produce their art work and give the public access to see it.

Only in Paris!

It would seem that there’s a very good reason every artist dreams of moving to Paris– and it’s not just the scenery…

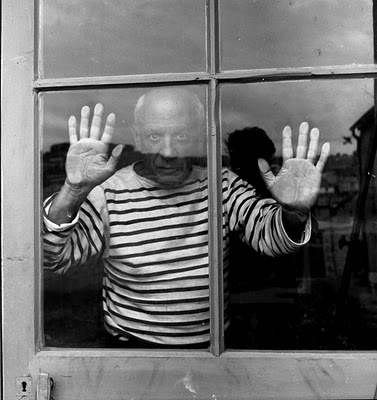

It took me a minute there to realize that ‘art squats’ are in fact a key part of Parisian history and its bohemian culture. Picasso’s Bateau-Lavoir, the infamous artists’ residence in Montmartre where he first discussed Cubism and painted Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon was indeed, a squat.

The Point Éphémère, a former factory on the Canal Saint Martin, today a trendy café, bar, exhibition space, concert venue, favorite hipster hangout and one of the most innovative cultural projects in the city right now– also started out as a squat in the 80s.

“This doesn’t mean that every squat is wonderful, but some obviously become part of a city heritage and must be preserved,” says Paris’ deputy mayor for culture, Mr. Girard. [NYT]

In a city where rent is going in one direction and one direction only– up; the bohemians are still able to survive and in many cases, get a better deal than most.

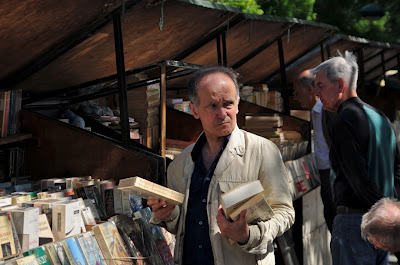

Take Paris’ Seine-side freewheeling booksellers known as the bouquinistes; where Hemingway and other great creatives of the Belle Epoque once browsed for a literary fix. As part of the French effort to preserve and encourage cultural heritage, all 200+ bouquinistes are today 100% free and exempt from paying taxes.

The mayor’s office even makes it a priority that the bouquinistes stay solvent. Back in the 18th century however, the bouquinistes would have been regularly chased across bridges and along the Seine by established bookshop owners who were losing business to the illegitimate sellers.

What would a romantic stroll along the Seine be today if the city hadn’t decided to help it’s squatting booksellers?!

What would the art world be if Paris had not become Picasso’s patron at a time when he was burning his own drawings to keep his fire burning in the winter?

Hungry for more Paris? The updated edition of Don’t Be a Tourist in Paris is now available.

Or become a MessyNessy Keyholder to gain access to our Travel eBook library and a direct line to our Keyholder Travel Concierge to plan your perfect trip. Need help planning a weekend in France? Need some restaurant recommendations for a remote village in the North Pole? We’re here to help.