Beachfront properties custom-built for movie stars and the Hollywood elite, panoramic views from the sand dunes stretching as far as Malibu, developed as “an isolated playground for the wealthy”– Surfridge, California was once one of the most coveted neighborhoods in Los Angeles. Today, it looks like this…

(c) Eyetwist on Flickr

(c) Houze on Flickr

(c) Cinemafia

The old street lights strangely still light up each night, but the residents they once shined for are long gone. Like a post-apocalyptic experiment, behind a barbed-wire fence, weeds are thriving through the cracks, overtaking the streets still lined with their iconic Hollywood palm trees à la Beverly Hills along the sidewalks. What’s left of demolished property walls can be found hidden behind thick bushes and disconnected power lines lie in the sun like scorched black worms.

(c) Atomic on Flickr

“Everybody who sees it now asks the same question: What the hell happened here?” says Duke Dukesherer, a business executive and member of the LA Historical Society who has written a book about Surfridge’s history, “It was paradise when I was a kid.”

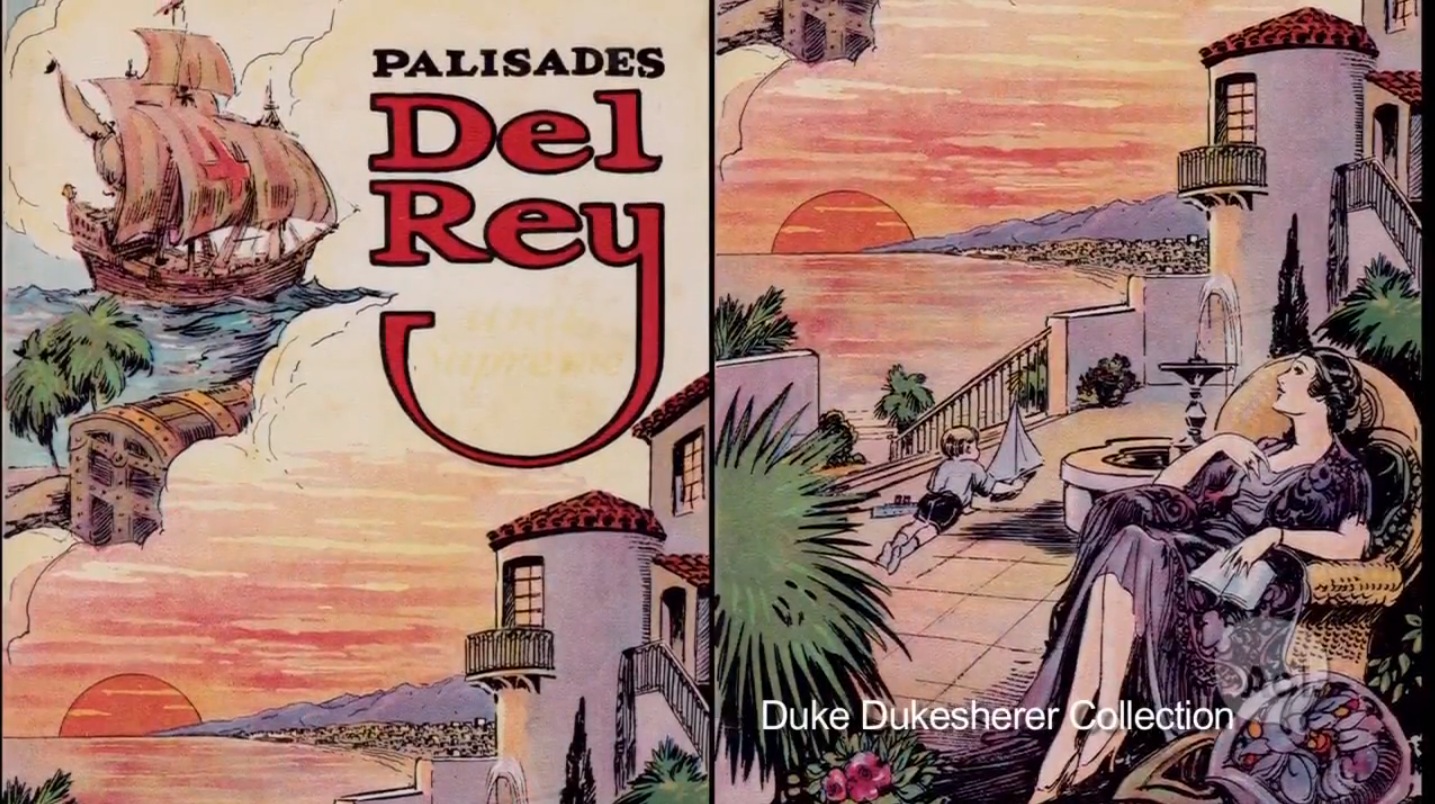

In the 1920s and 30s, Surfridge was developed as an idyllic beachside community in a district of Los Angeles known then as Palisades Del Rey (Playa del Rey) and billed as “The Last of the Beaches”.

The Great Depression had initially stalled the project, but by the 1930s, the lots were snatched up by an expanding upper middle class and the Hollywood elite, including director Cecil B. Demille. It was comprised of over 800 homes, mansions and cottages alike, on 470 acres, and there was a small airfield nearby which opened in the late 20s where local residents could enjoy the occasional propellor plane air show.

By the early 1970s, all 800 homes had been ‘removed’ and that ‘little airfield’ was fast-becoming one of the busiest airports in the world– LAX.

“If you lived in Surfridge prior to the late 1950s, you had to raise your voice a bit when having a conversation. After the jets came, you had to literally stop talking when they took off,” remembers Duke. By the end of World War II, commercial flights in and out of Los Angeles were fairly frequent and flying low, right over Surfridge. Most residents tolerated the propellor planes but when the Jet Age arrived, the residents lost the battle and the dream of Surfridge was over.

After a decade of the town’s complaints, anger and lawsuits, residents found themselves being forced out of their homes on grounds of health and safety hazards. The shattering jet noise was cited as a gross zoning violation and the idyllic beachfront cottages and houses were suddenly condemned properties. Offered only a fraction of what their properties would be worth today by the government, some home owners tried to stay, but after the fourth and final round of forced condemnations by the City of Los Angeles and LAX, eventually all houses were either demolished or ‘removed’ from the area. Surfridge was wiped off the map and suddenly became one of the most expensive pieces of barren land in the country.

Below: (c) Google, (c) Bryan Reynolds

Deserted Surfridge land plots, just west of the LAX runways

Sea view of Surfbridge, which lay at lay at an elevation of 135 feet (41 m)

The Los Angeles Times recently reported that a $3-million plan to fix what many see as an eyesore has been approved by the California Coastal Commission. LAX airport will be footing the bill.

“Some streets, curbs, sidewalks, home foundations and utilities visible to neighboring homeowners will be removed. Six acres will be reseeded with native plants — sagebrush and goldenbush, primrose, poppies and salt grass among them — that will return this sliver of dunes back to where it was a century ago,” writes LA times reporter Mike Anton.

(c) Stonebird on Flickr

But to say Surfridge is completely void of residents today wouldn’t be entirely true. The area is now a federally protected habitat for the endangered El Segundo blue butterfly. The species is now flourishing thanks to the 200-acre butterfly preserve and more than 125,000 new butterflies take flight each summer. Managed by the city of Los Angeles, the area has been reintroduced to its native buckwheat plant, where the El Segundo butterflies feed and lay their eggs. And they don’t seem to mind the noise.