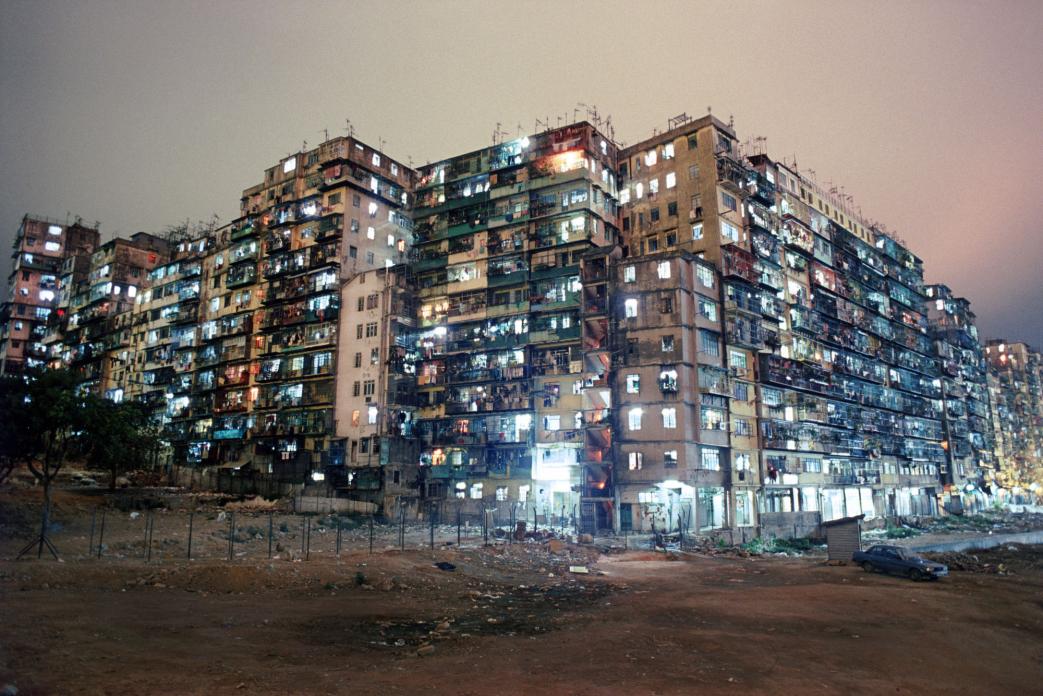

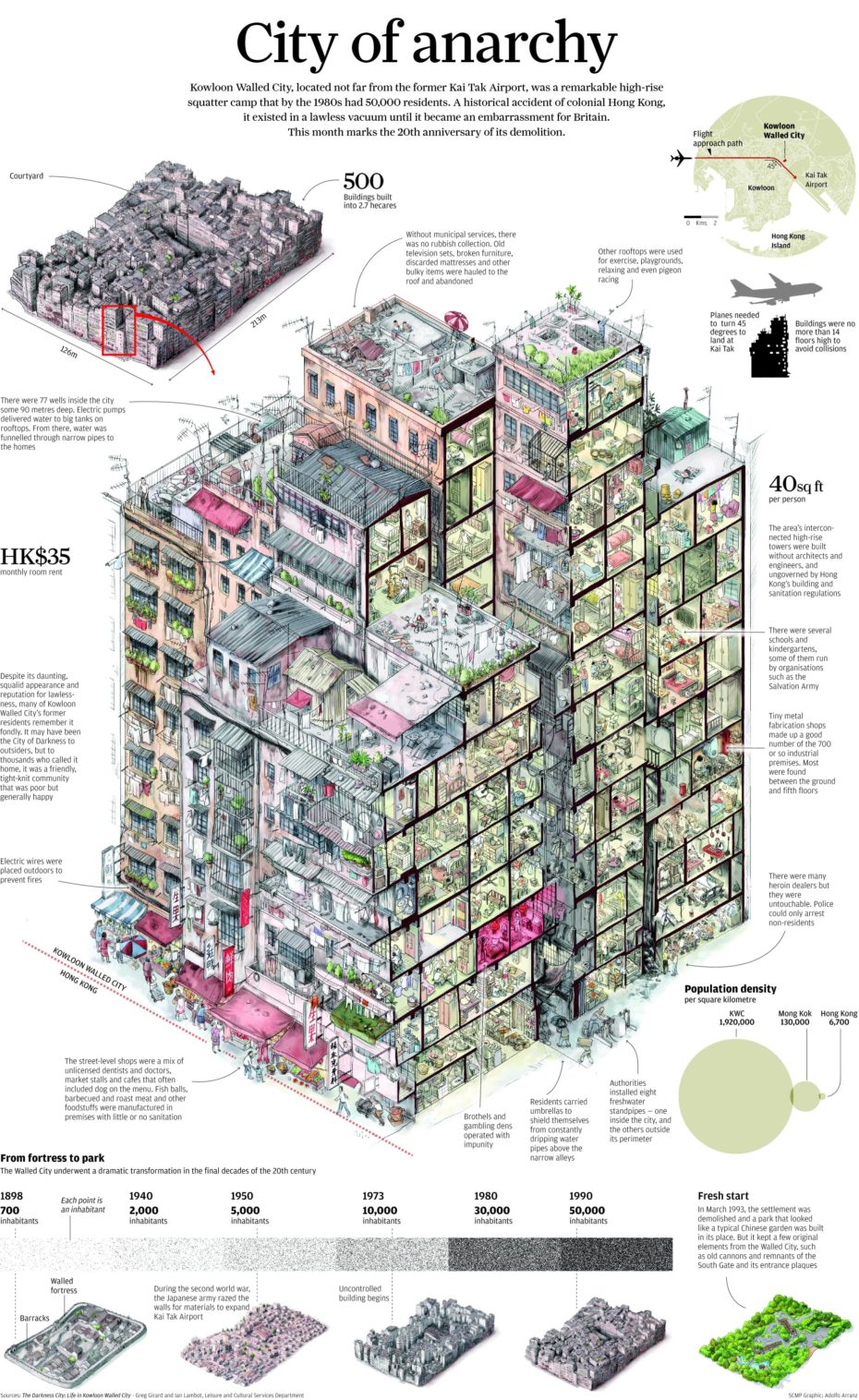

It was the most densely populated place on Earth for most of the 20th century, where a room cost the equivalent of US$6 per month in high rise buildings that belonged to no country. In this urban enclave, “a historical accident”, law had no place. Drug dealers, pimps and prostitutes lived and worked alongside kindergartens, and residents walked the narrow alleys with umbrellas to shield themselves from the endless, constant dripping of makeshift water pipes above.

Ungoverned and unregulated, Kowloon Walled City was for so many years, a stain on the urban fabric of British colonial Hong Kong. It has now been over 20 years since the city was finally demolished and a fascinating and detailed info-graphic shows what life was like inside the city of darkness… (click to enlarge)

“There was a place near an airport, Kowloon, when Hong Kong wasn’t China, but there had been a mistake, a long time ago, and that place, very small, many people, it still belonged to China. So there was no law there.”

– William Gibson, Idoru

The history of the Kowloon Walled City can be traced back as far as the Song Dynasty (960–1279), when it was used as an outpost for managing the trade of salt, but it wasn’t until the British colonists came knocking that Kowloon would become associated with anarchy and lawlessness. By the 19th century it was a walled military fort which the Chinese decided to hold onto after Hong Kong Island was ceded to Britain in 1842– or as William Gibson puts it plainly, ‘when Hong Kong wasn’t China‘. It was China’s way of keeping an eye on the British (much to their annoyance) from a very convenient location, right in the middle of the newly colonized territory.

Kowloon ‘Walled’ City lost its wall during the Second World War when Japan invaded and razed the walls for materials to expand the nearby airport. When Japan surrendered, claims of sovereignty over Kowloon finally came to a head between the Chinese and the British. Perhaps to avoid triggering yet another conflict in the wake of a world war, both countries wiped their hands of the burgeoning territory.

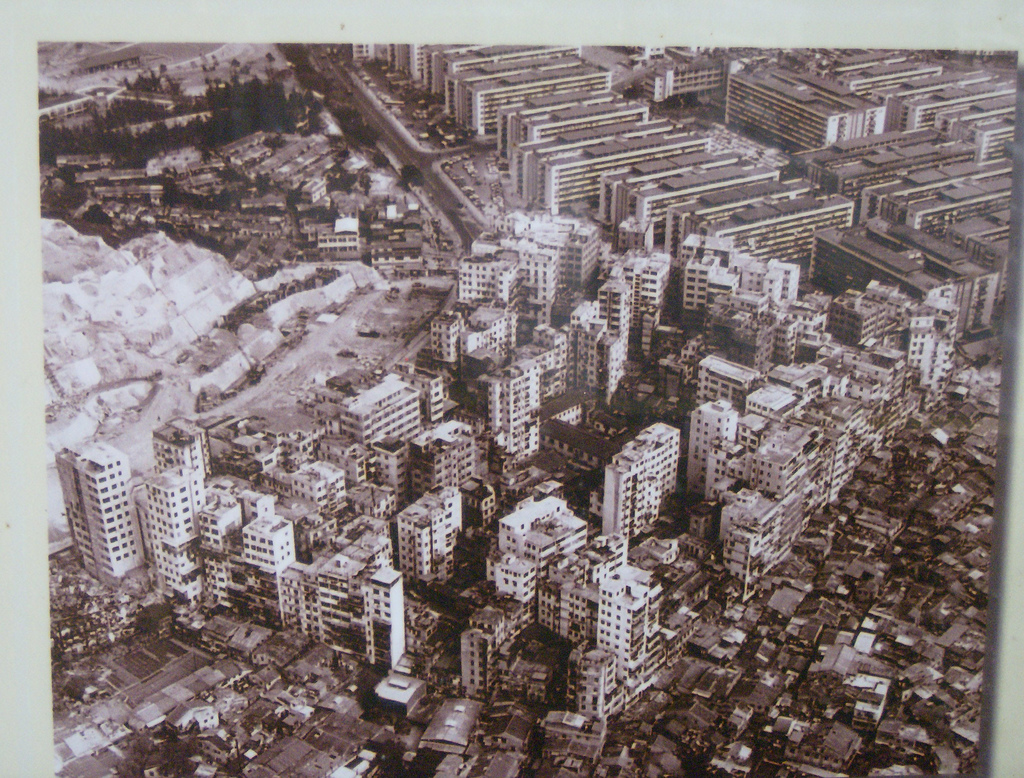

And then came the refugees, the squatters, the outlaws. The uncontrolled building of 300 interconnected towers crammed into a seven-acre plot of land had begun and by 1990, Kowloon was home to more than 50,000 inhabitants. Author William Gibson continues with his notes on the city:

“An outlaw place. And more and more people crowded in; they built it up, higher. No rules, just building, just people living. Police wouldn’t go there. Drugs and whores and gambling. But people living, too. Factories, restaurants. A city. No laws.”

A 1989 Germany documentary takes us on a fascinating tour of the city:

In the 1980s, photographer Greg Girard documented Kowloon Walled City…

Full photostory here

Despite earning its Cantonese nickname, “City of Darkness”, amazingly, many of Kowloon’s residents liked living there. And even with its lack of basic amenities such as sanitation, safety and even sunlight, it’s reported that many have fond memories of the friendly tight-knit community that was “poor but happy”.

“People who lived there were always loyal to each other. In the Walled City, the sunshine always followed the rain,” a former resident told the South China Morning Post.

But as the community began to fascinate architects, photographers and eventually the media, the embarrassment of such living conditions could no longer be tolerated. The site was raised and HK$ 2.7 billion was spent on relocating its residents.

Today all that remains of Kowloon is a bronze small-scale model of the labyrinth in the middle a public park where it once stood.

This isn’t to say places like Kowloon Walled City no longer exist in Hong Kong….

A Modern-day Kowloon: Chungking Mansions

A citadel known as the Chungking Mansions is often compared to Kowloon Walled City for its unusual atmosphere, where some 5,000 people from at least 129 different countries are living, working (and lurking) in relative lawlessness….

The Economist decribes the atmosphere at Chungking Mansions in 2011:

“Teeming, crumbling and motley in the extreme, it is a structure to attract or repel the people of Hong Kong […] Pushtun touts, Nigerians slinging fake Rolexes and a flock of Indian prostitutes in garish saris congregate at its maw. Inside, a glittering and stinking confusion of shops, food stalls and dormitories is piled on itself in an impossible jumble—17 storeys high and covering most of a city block. Is it even a building?”

Dubbed a “Ghetto at the Centre of the World” by anthropologist Gordon Matthews, Chungking was built in 1961 supposedly as a residential building, but today contains more than 90 low-budget hotels, as well as countless curry restaurants, African bistros, mobile phone shops, sari stores, and foreign exchange offices. A tight gathering place for many ethnic minorities in the city, journalist Peter Shadbolt of CNN called it the “unofficial African quarter of Hong Kong.”

In its darkest days during the 80s and 90s, Chungking Mansions was an squalid centre for drugs, gangs and criminal activity, and yet recently, it was elected as the “Best Example of Globalization in Action” by TIME Magazine and has become somewhat of a Hong Kong legend with adventurous tourists. The Lonely Planet guides features Chungking Mansions as 17th out of the 1010 things to do in Hong Kong, and lists it as second out of the 157 architectural and cultural sites in Asia.

A living hell? Or a limbo filling the gap between different economies, where ethnic minorities and asylum workers can hold more cash in their hands at one time than some might have held in their entire lives…