Guest Article by Chicago Sun Times columnist, Neil Steinberg

Chicago is justly famous for its architecture. Birthplace of the skyscraper, home to the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere (still, the emotion-driven claim by New York’s One World Trade Center, based on the dodge of calling an antenna a spire, is easily dismissed) Chicago offers a panorama of architectural marvels. So many icons that you usually have to live here before you start noticing structures that are not famous and important, but merely intriguing and fun. Such as the charming little fake buildings that electrical company Commonwealth Edison puts up to camouflage its substations.

It can take a while, walking past, until you realize that the front doors don’t open. Or what look like windows are actually louvers. What is that? you wonder.

And what is it doing there?

The most noteworthy, a faux Georgian mansion in the River North area of downtown, was designed by perhaps the city’s most famous living architect, Stanley Tigerman, former director of the School of Architecture at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

“The building is somewhat tongue-in-cheek , a bit of a joke,” said Tigerman, who had first designed a restaurant just west of the site. “The Hard Rock Cafe: fake stucco, fake Georgian, nothing real about it. Then they came to me and wanted me to do the ComEd substation next door, but to be contextual, to relate it to this ersatz piece of junk.”

So rather than construct a bogus building based on a fake, albeit one he designed, Tigerman cut the other direction.

“I decided to go absolutely hard core, as classically designed as I could, done authentically Georgian,” he said. “The brick bonding is English cross bond, the one Mies van der Rohe used whenever he used brick. It’s very expensive to to lay bricks that way, but it makes the walls sturdy and impervious to cracking. I knew the building would never receive any maintenance, so the idea was to do as good a building as I could.”

He also had to take into account the building’s true purpose — so if you look closely, what seem to be windows are actually vents, to help cool the 138 kV electrical transmission equipment inside.

This is basically what a substation looks like unmasked:

(Substations are used to shift electrical current from high voltage to levels usable by customers, containing circuit breakers, transformers and other apparatus).

Nor is Tigerman the only architect of note to do a Chicago substation. Holabird & Root, which created such deco gems as the Palmolive Building, with its distinctive beacon, and the Chicago Board of Trade, topped with its stainless steel Ceres sculpture, also designed the ComEd substation across Dearborn from Daley Plaza, in the heart of downtown, an enigmatic structure with an enormous black doorway but no door, topped by a lintel carving that gives away the game.

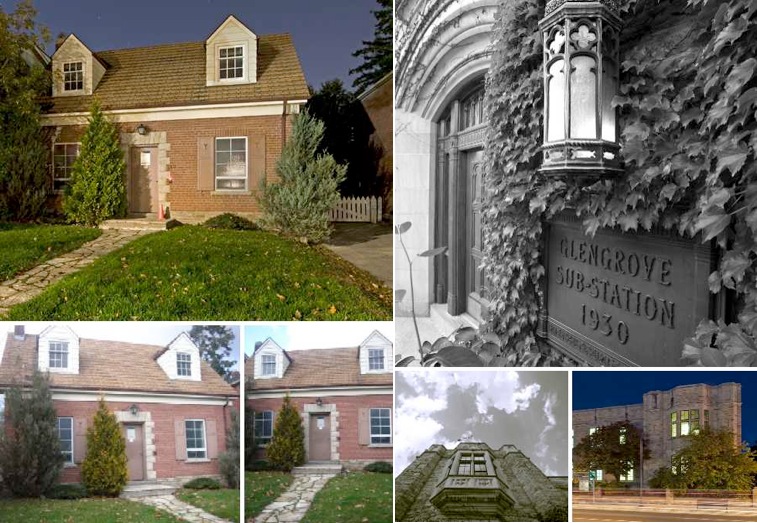

Other cities also apply unexpected artistry to hiding their electrical infrastructure. In Anaheim, California, a community park was built over a substation. Toronto Hydro is even more energetic, disguising its substations as tract homes and office buildings.

(images of Glengrove substation and Salt Boxes in Toronto via WebUrbanist by BlogTO / Alice in Search of a City /PhotoSensitive / BlogTO)

Disguising the substations serves a dual purpose. While primarily to help blend the otherwise unsightly electrical equipment into their neighboring communities, they also help protect what’s inside by hiding it. With copper selling at $3.20 a pound, thieves have been known to break into the unmanned substations and steal the copper from live electrical equipment, as dangerous as that is. But that isn’t a problem if the would-be robbers don’t know the equipment is there, hiding in plain sight.

About this contributor

Neil Steinberg is a daily news columnist at the Chicago Sun-Times.

Neil Steinberg is a daily news columnist at the Chicago Sun-Times.

He blogs at everygoddamnday.com, and his latest book, “You Were Never in Chicago,” was published by the University of Chicago Press last year.”

Find Neil’s blog here.