In 1858, on the prospect of building a tunnel that would link up Britain and France under the channel, the British prime minister asked, “Why shorten a distance we already find too short?”

The idea was allegedly first brought to the table by Napoleon Bonaparte himself, after a French engineer, Albert Mathieu, had approached him with a proposal to build a sub-sea tunnel, lit by oil lamps and designed for horse-drawn carriages.

Over in London however, the idea was not so welcome. Despite a brief peace treaty in 1802 during the Great French Wars that called for an end to hostilities between the two nations, Napoleon wasn’t popular with the British. Only a year later, France was once again preparing for war with England and the vision of the channel tunnel was thwarted, believed to be just another part of Napoleon’s plan to invade Britain.

Sixty years later, pilot tunnels were being dug at both sides of the channel. They made it about 6,000 feet in on either end before the entire project was abandoned again in 1882, pressured by British political and press campaigns claiming the tunnel would compromise Britain’s national defences. The original early works of this abandoned construction were encountered almost a century later during another failed effort to revive the project in 1974.

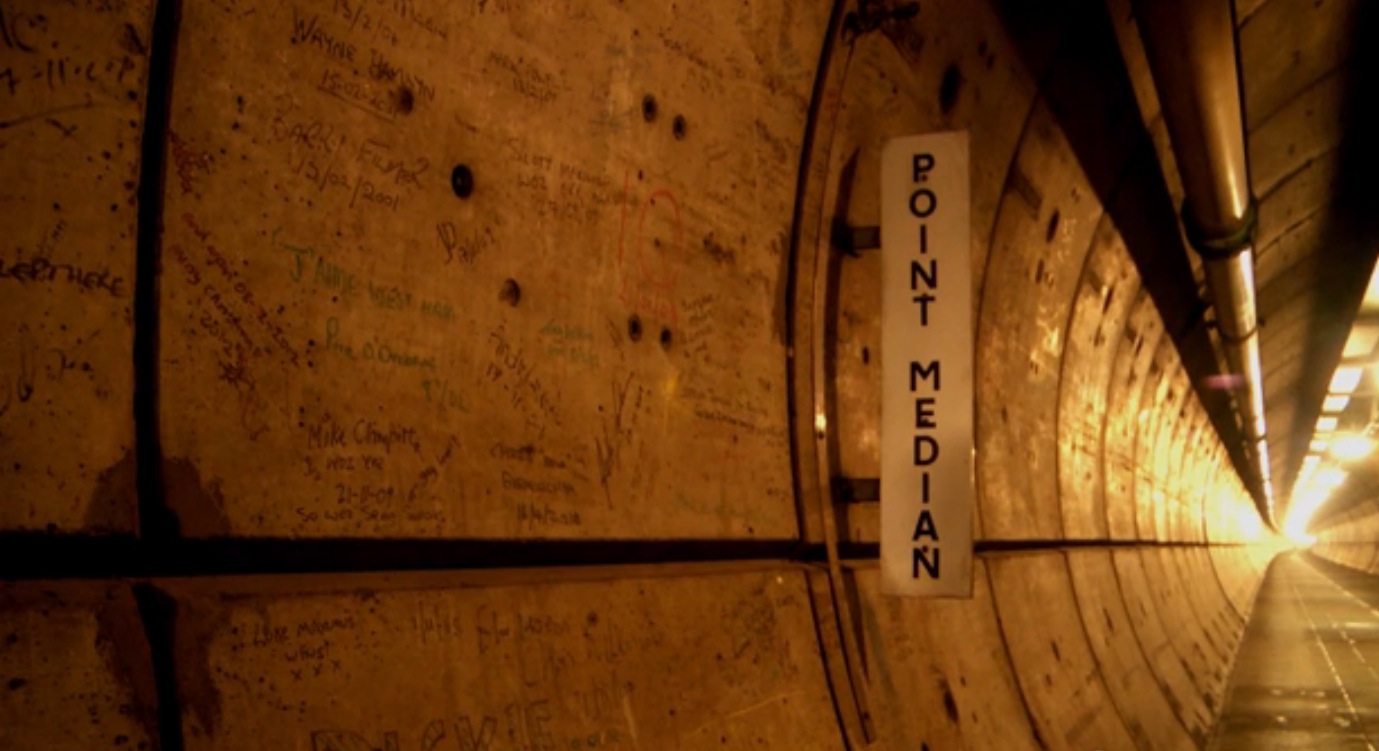

You could say the Eurotunnel has been in the works for more than two centuries, stalled again and again by various political or financial spanners thrown into the works. As a result, it’s a bit of a patchwork of failed and revived attempts. Courtesy of the Telegraph, Eurotunnel spokesman John Keefe gives us a glimpse of this patchwork as he takes us on a tour through the service tunnel, first dug in the 1870s, rarely seen by the public.

“This is a really unique environment, I don’t think there is anywhere else like it in the world, there’s no other tunnel that creates such a link between an island nation and a continent.”