Some thirty thousand people visit the Notre Dame de Paris everyday, but little-known to tourists or even to the Parisians that pass by it on their daily commute, there was once a much more popular yet sinister attraction that shared a backyard with the historic cathedral, capable of luring up to 40,000 visitors in a single day. That attraction was the Paris Morgue.

There aren’t many other ways to describe the Paris Morgue during the 19th century other than as a place of entertainment, for Parisians and tourists alike.

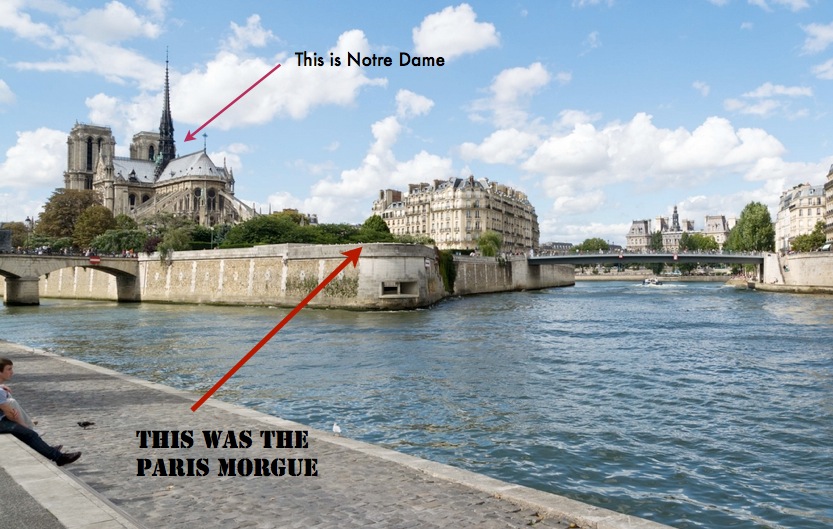

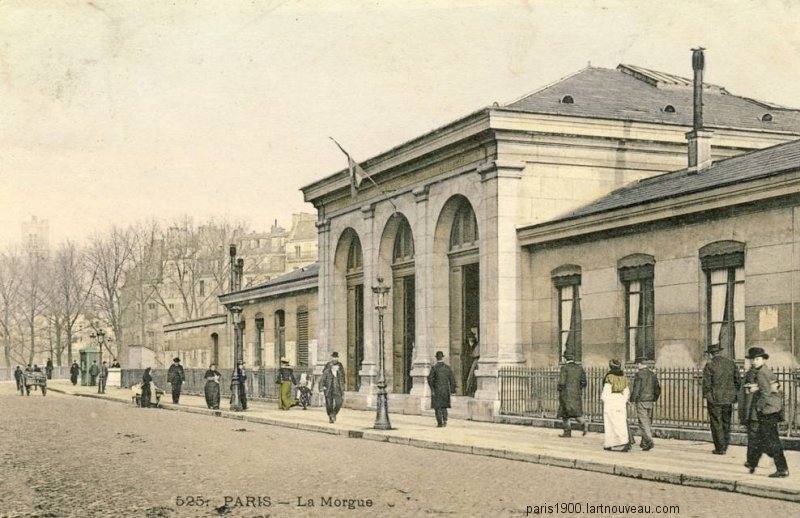

Conveniently located behind the Notre Dame on the southern tip of the Ile de la Cité, built in 1864, the original purpose of the morgue was of course not to attract tourism but to identify unknown bodies found in the city; many that had been fished out of the Seine or suicides that no one had reported missing.

Conveniently located behind the Notre Dame on the southern tip of the Ile de la Cité, built in 1864, the original purpose of the morgue was of course not to attract tourism but to identify unknown bodies found in the city; many that had been fished out of the Seine or suicides that no one had reported missing.

Find the Paris morgue print on Madame Talbot.

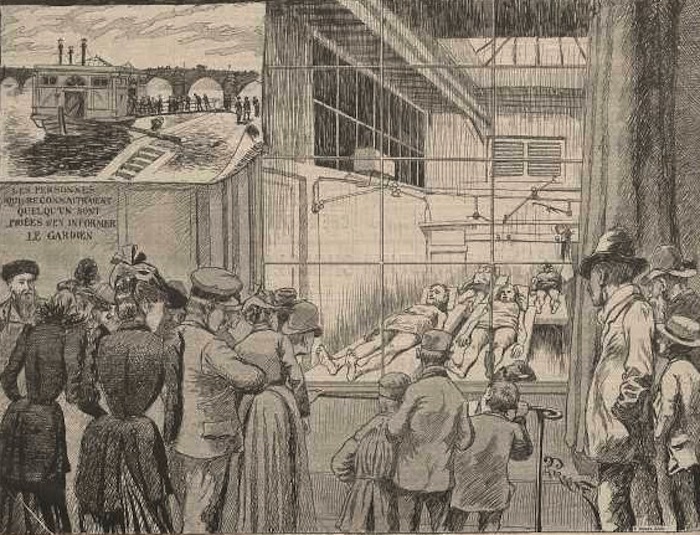

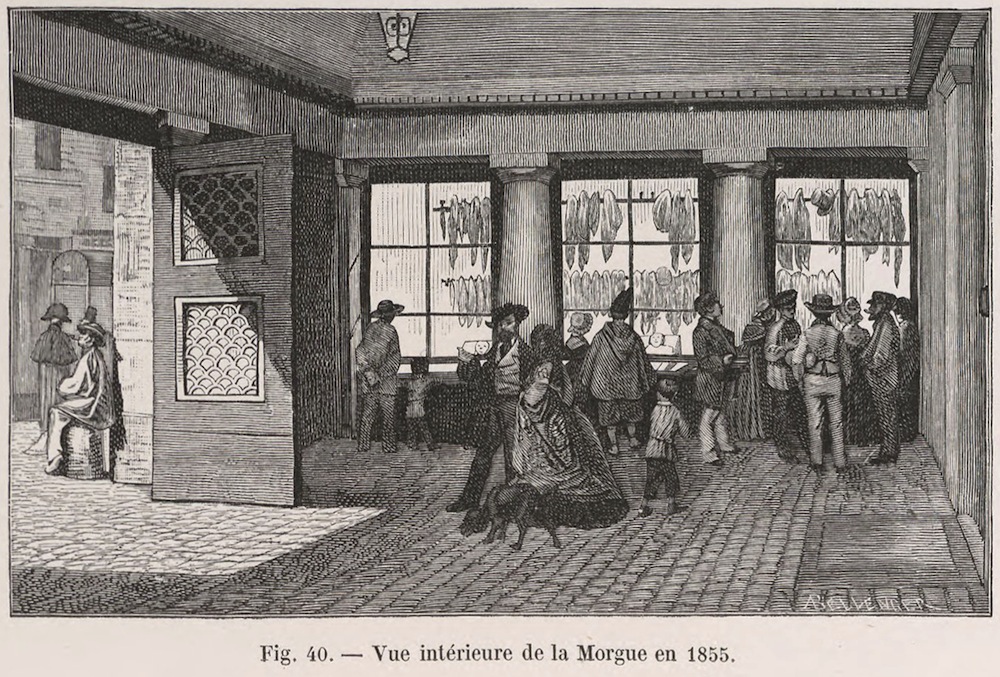

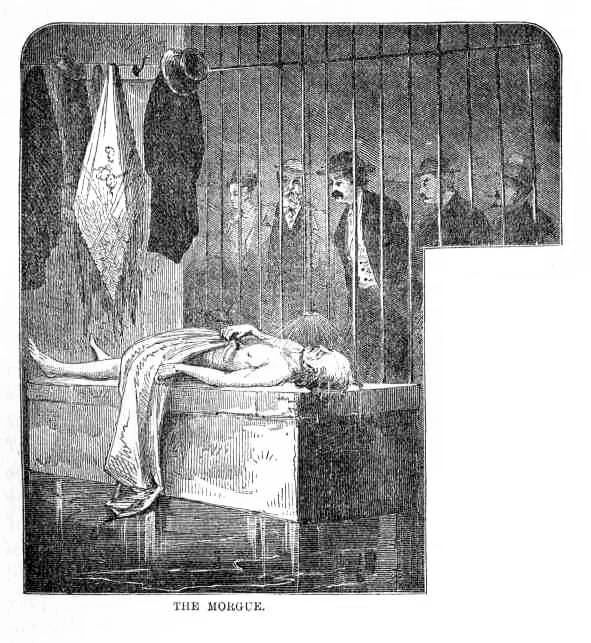

Their unfortunate remains were displayed on slanted marble tables behind glass, inviting friends and families to claim the deceased. Word of the morbid (and free) exhibition of dead bodies quickly spread, and soon the morgue became a fixture on the Parisian social circuit, enticing the curiosity of men, women, even children from all social backgrounds, who would visit regularly, filing past the grisly display, providing themselves with at least a week’s worth of fresh gossip on the possible identities of the corpses and causes of death.

Outside on the Quai de l’Archevêché, street vendors catered to the crowds that flocked to the morgue, peddling cookies, gingerbread, coconut slices and other touristy fairground treats of the era.

“There are few people having visited paris who do not know the Morgue”, wrote Parisian social commentator Hughes Leroux in 1888. Listed in practically every guidebook to the city, a fixture of Thomas Cook’s tours to Paris, and a “part of every conscientious provincial’s first visit to the capital”, the Morgue had both regulars and large crowds of as many as 40,000 on its big days. Despite its location in the shadows of Notre-Dame, its deliberately undramatic facade and its seemingly somber subject matter, the Morgue was “one of the most popular sights in Paris. The identification of dead bodies was turned into a show. This was public voyeurism– flânerie in the service of the state; it was”part of the cataloged curiosities of things to see, under the same heading as the Eiffel Tower and the Catacombs.”

–Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siecle Paris, by Vanessa R. Schwartz.

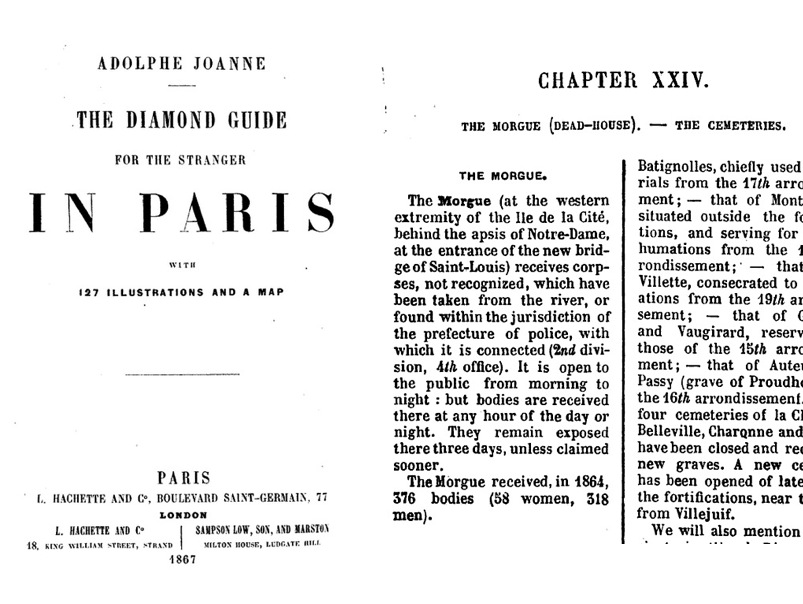

Indeed, the Paris Morgue was listed in many of the top travel guidebooks for Paris. Charles Dickens was known to be a frequent visitor and describes the Paris Morgue in several of his journals as an “old acquaintance”, and “a strange sight, which I have contemplated many a time during the last dozen years”.

Here is a scanned copy of the The Diamond Guide to Paris, from 1867:

Of the three large doors at the front, the middle one remained shut and visitors filed through, entering at the left and exiting at the right, prompting the Morgue’s registrar to comment that it was nothing more than an ‘entresort’ (a carnival atrraction one paid to see by walking through a barrack and gaping at the sight within)– Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siecle Paris, by Vanessa R. Schwart.

It was open everyday from dawn until 6pm; a three story box of icy cold air on the larger of the two islands in the centre of Paris. To delay decomposition of the bodies, cold water was dripped continuously from overhead taps, the victims’ clothes and belongings hung on pegs behind them.

This short story by Arthur Mark Cummings for the Harvard Crimson gives a vivid idea of a typical visit to the morgue…

Brutal, gashed, and swollen faces; wide gaping mouths, which opened for the last time to utter the death-shriek, dead, sodden eyes, ghastly smiles, faces of men and faces of women, faces of the young and faces of the old; faces which Dante, groping among the damned, might have dragged from hideous, steaming depths of Lethean mud, and flung forth to front the unwilling eye of day– such is the sight which greets the visitor upon his entrance to the Paris Morgue. Some of the corpses had been in the water a day, some a week, some-nobody knew how long. Some were clothed, some were naked; some lacked an arm or leg or head, some lacked everything except a single leg or arm, which came up in the net of some fisherman, with a few rags of cloth clinging to it. We sicken at the fearful list. Let us press on into the interior of the building.

Men are crowding and elbowing each other; old hags are pointing toward the glass, and croaking to one another; pretty women are gazing with white faces of pity, but with none the less thirsty greediness, upon some fascinating spectacle; little children are being held aloft in strong arms, that they too may see the dreadful thing, and they do see, and they toss their tiny, wavering arms aloft and crow right gleefully.

The objects of Interest are four corpses, which are lying upon iron frameworks behind the glass … One is an old woman … another is a young girl, who is dressed in silk and whose dark hair is still coiled neatly … She bears no wound, but upon the small, coquettish face is stamped such a look of horror as it might well break a mother’s heart to gaze upon. A middle aged man, short, thick-set and resolute looking, has dropped dead in the street, and the gendarmes have brought the nameless body here. Unnamed and unknown, he will lie in the public pits of Pere Lachaise.

In 1907, the morgue finally closed to the public, out of concern for morality. Upon its closure, newspaper columns lost their visual auxiliary for the popular reports on horrible accidents and sensational crimes. One journalist complained:

“The Morgue has been the first this year among theaters to announce its closing. As for the spectators, they have no right to say anything because they didn’t pay. There were no subscribers, only regulars, because the show was always free. It was the first free theater for the people. And they tell us it’s being canceled. People, the hour of social justice has not yet arrived.”

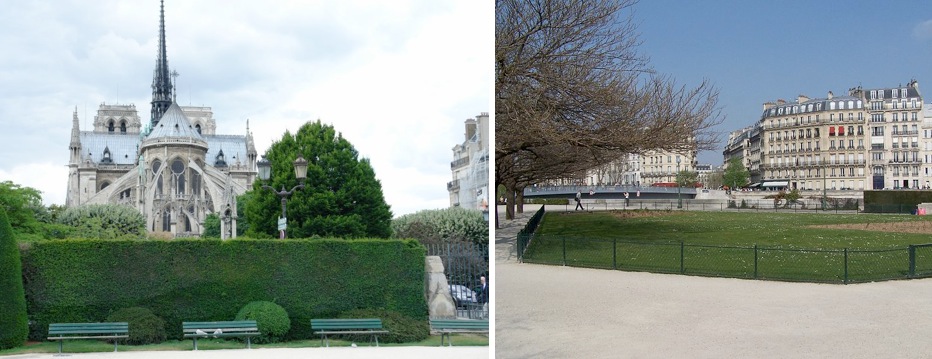

A morgue with a view …

Today, in the exact spot where the Paris morgue was located from 1867-1907, stands a public garden, “Square de l’Ile de France”, with a memorial to the WWII Nazi deportation. Access to the garden where the morbid attraction once lured visitors away from Notre Dame is located at 1 Quai de l’Archevêché, just a few feet from where tourists traditionally take a romantic pause to attach their “love padlocks” on the bridge, blissfully unaware of the dark history behind this scenic Parisian spot.