The briefcase was found three decades after the affair took place, abandoned in a German apartment and later sold at auction. The contents of the suitcase, an extraordinary collection of materials that chronicled the adulterous relationship between a businessman and his secretary in the late 1960s and 70s.

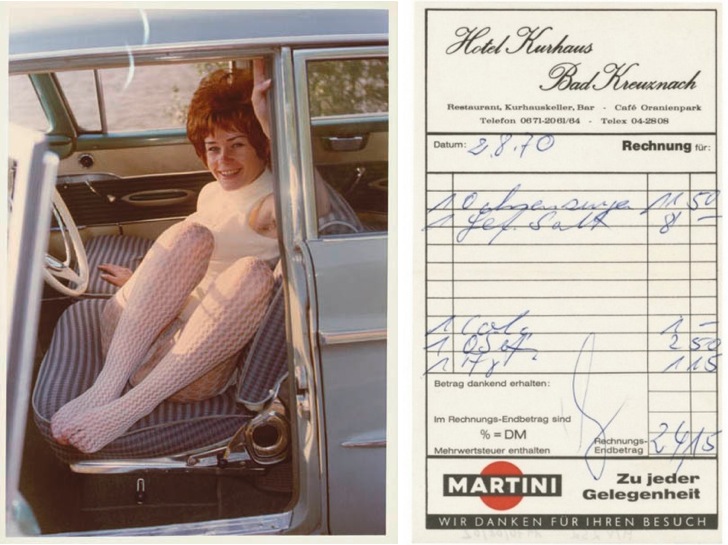

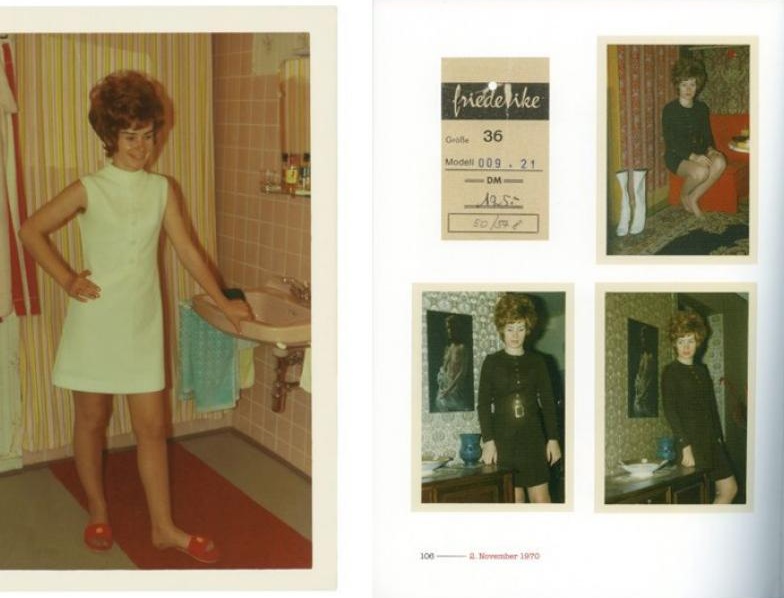

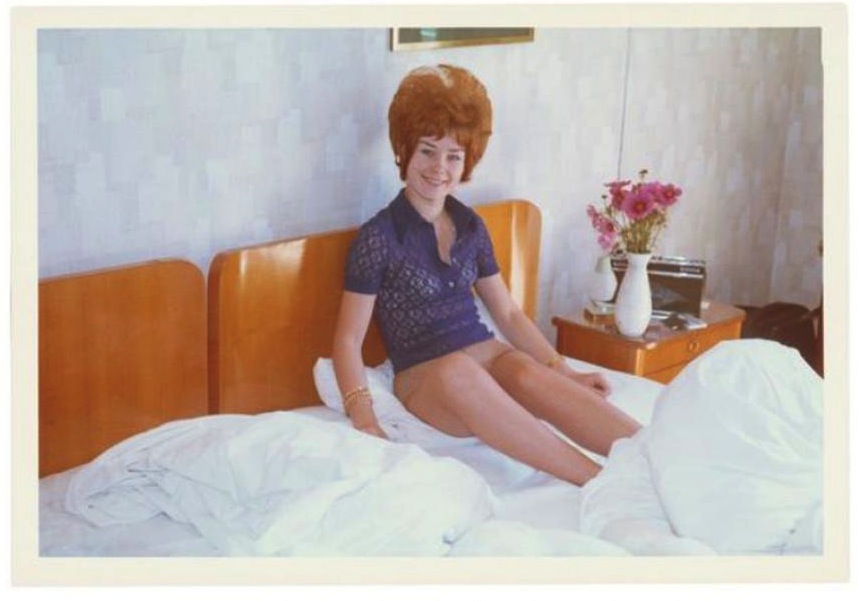

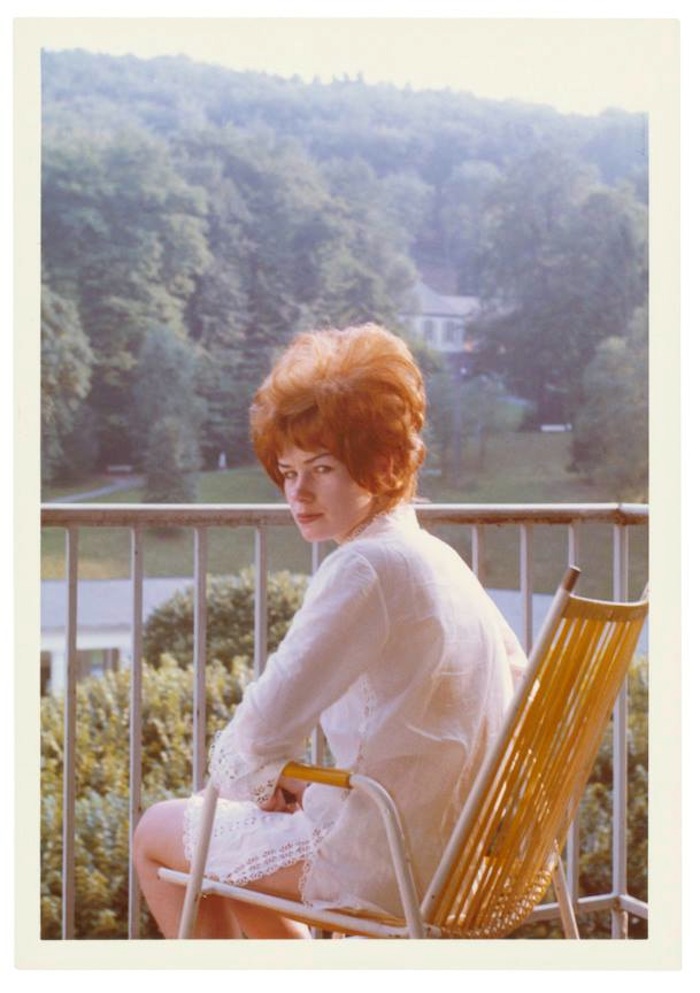

Exposed to our own voyeurism, a recent exhibition in New York invited the curious to discover an archive consisting of hundreds of photographs of the same woman, identified only as “Margret S,” posing in hotel rooms and enjoying secret getaways.

Her illusive lover and man behind the camera, is married Cologne businessman and construction company owner, Günter K. He is 39 when the affair begins in May 1969, and Margret is 24, also married.

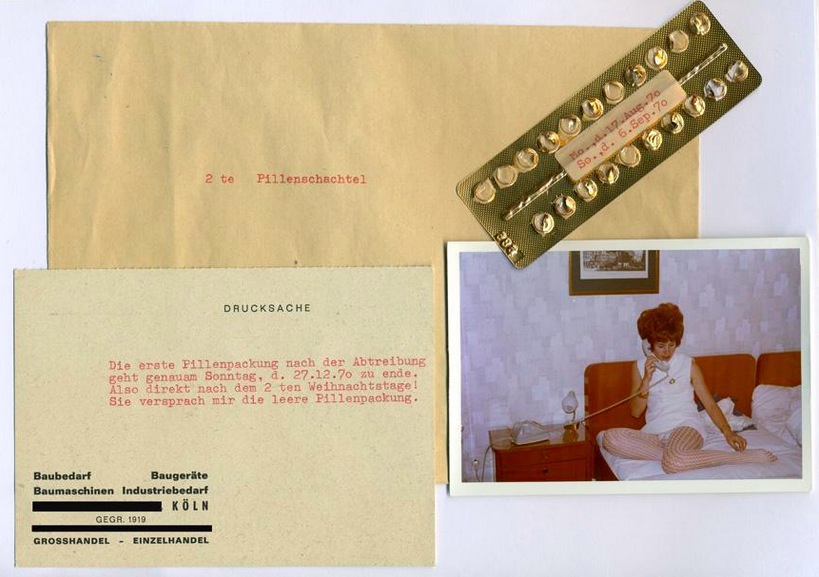

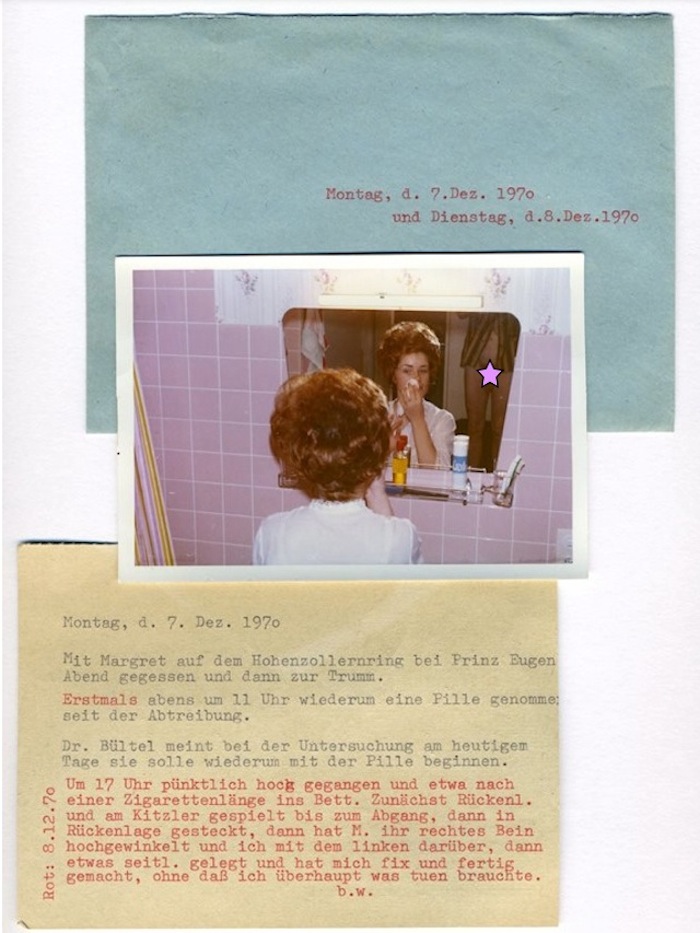

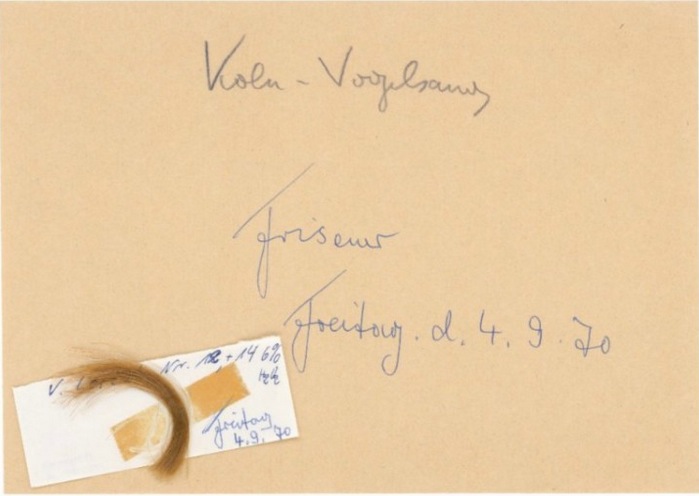

We know this because Günter meticulously documented the affair like a compulsive accountant. Not only did he endlessly photograph Margret, but he took detailed notes of the affair, written with a typewriter and inscribed with dates like they were official records.

He kept receipts from hotels, restaurants, casinos, spas and shopping sprees, as well as travel documents, theatre tickets and even held on to empty contraception packets and had samples of Margret’s hair.

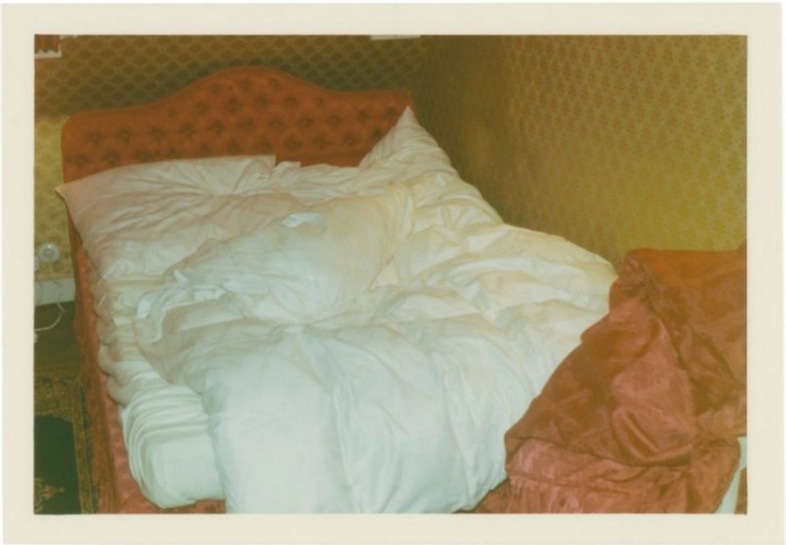

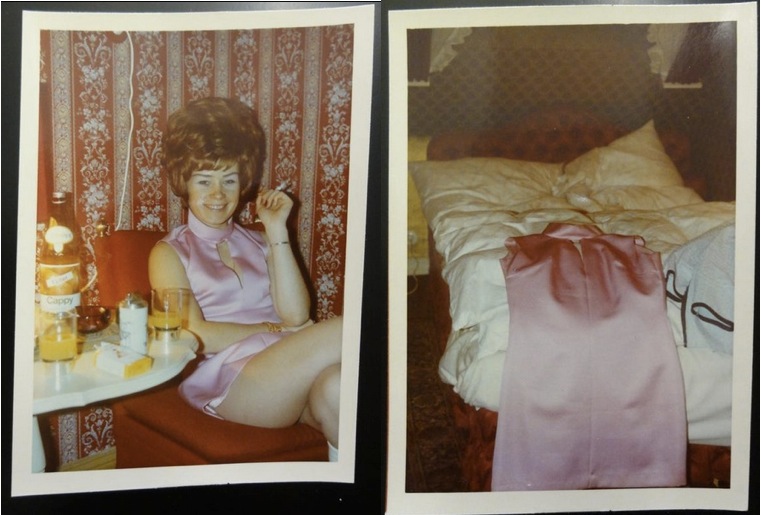

“The couple go on ‘business trips’ in Günter’s Opel Kapitän,” observes curator Veir Loers in his introduction to the original exhibition of ‘Margret’ in Austria. “Then the trysts begin to take place in an attic flat in Günter’s store building … Margret prepares roulades and redfish filets with cucumber salad. They drink Cappy (orange juice) with a green shot (Escorial, strong liquor) and watch “colourful television.” Margret dresses for him in the clothes he has bought her.”

Where most adulterers would go out of their way to cover their tracks, Günther essentially publicised his affair and produced all the evidence a jaded wife could ever need.

Indeed, his notes reveal that his wife Leni is aware of the affair but chooses to endure the humiliation. In one of the first long notes, typed on a page from a calendar, Günther describes a confrontation between Margret and his wife:

[Roughly translated from German]

Monday 7.9.1970: At lunch Leni (Günthers wife) says to Margret: Madame, you are a lesser character, you are disrupting a good marriage.

Tuesday 8.9.1970: Around 10 a clock Margret says to me: You let this insult from your wife against me pass? No more sex, you can jump on your own wife. Whatever you do, you are not allowed to jump on me anymore.

Later, my wife has to apologize to her at lunch on 8.9.1970.

That afternoon they go upstairs again to make love and the note ends with:

Devil salad is eaten. Everything is okay again.

The affair takes place at the dawn of the sexual revolution and yet old conventions prevail. One only hopes he didn’t type up his reports in the living room accompanied by his wife. Or would it even make a difference?

“He, the perfect lover, in truth is a macho man who wants to have everything under control”, concludes curator Veit Loers, who was first to exhibit the archives. “She [Margret] enjoys his attention, his generosity, is happy to let herself be manipulated, is jealous, becomes pregnant despite the pills, and has an illegal abortion − for the third time in her young life.

As the voyeur, we find ourselves in an even more conflicted space as the obsessive nature of the relationship becomes increasingly obvious.

During one of their “business trips”, Günther makes a list of all the times they made love….

Wednesday 12 Aug. 1970: 17 18.15 1x

Beginning of her period (tampon) Initiation party anyways.

Tuesday 18 Aug. 1970: 15.15 -15. 20.

Yellow chair in front of the aquarium (sitting) 1x

Wednesday 2 Sept. 1970: 17. 05-18.00 1x

With beautiful music, resting afterwards

As the affair progresses, his descriptions get longer, become more bold and explicit.

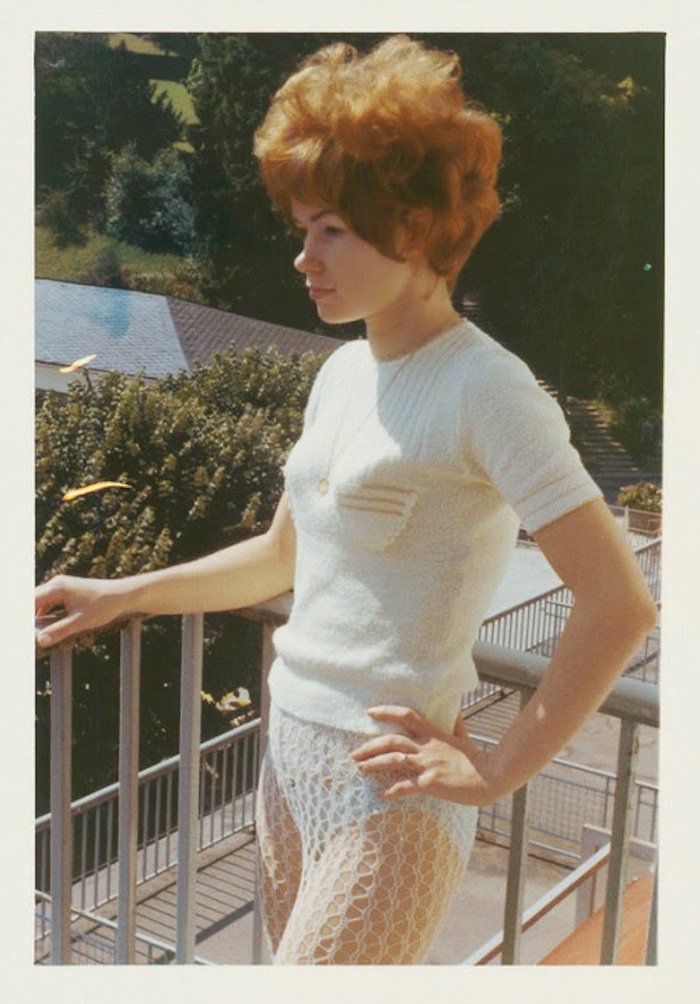

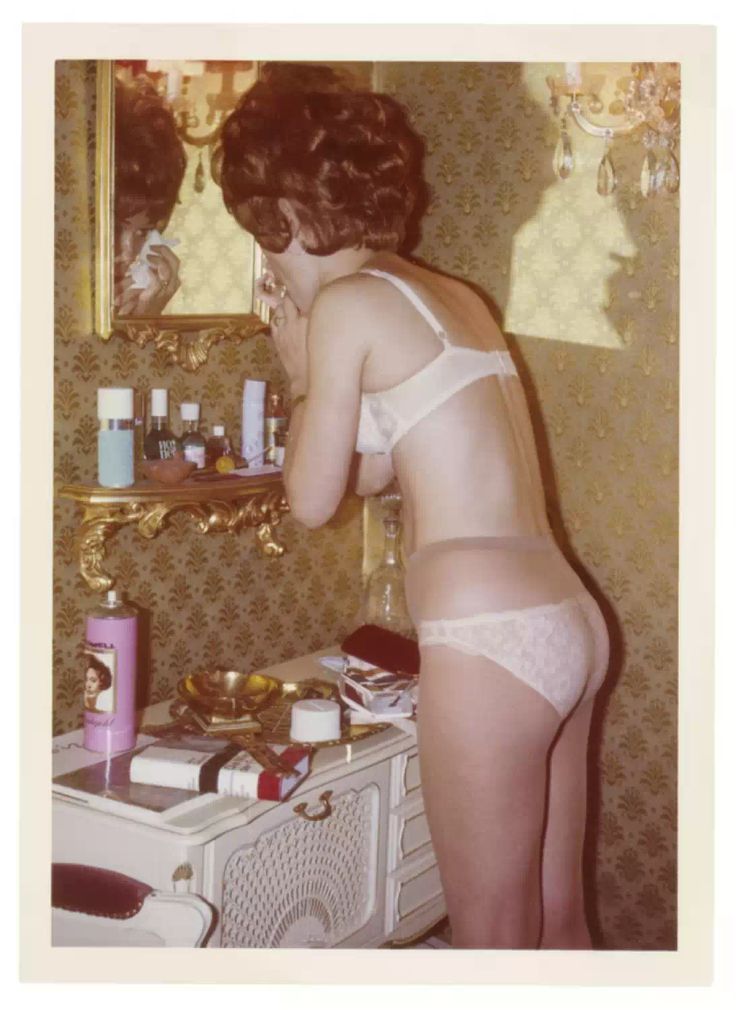

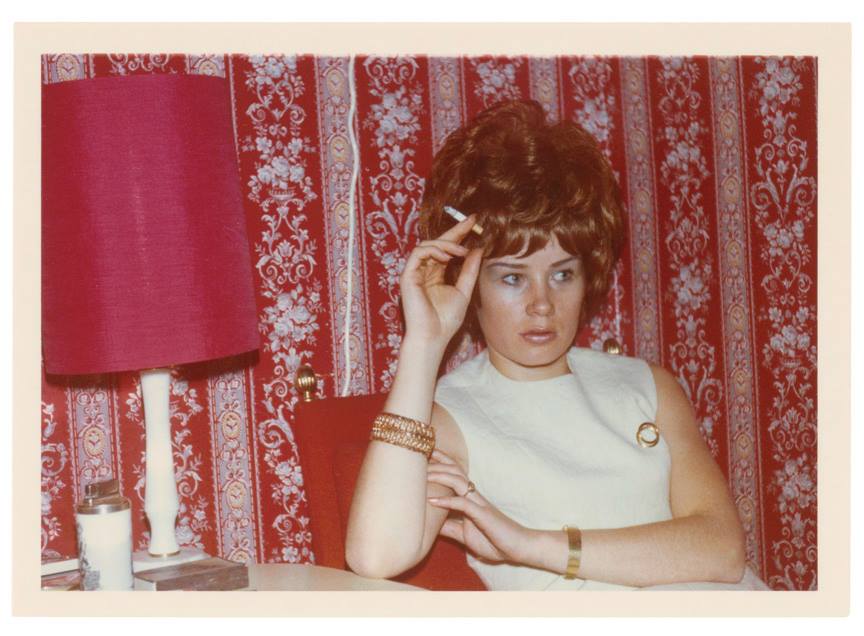

From the earlier black & white photos to later ones, we also observe Günther’s apparent transformation of his secretary from a shy, simple, mousy-haired girl to a modern, sophisticated woman with a fiery red high-maintenance beehive do.

She loses the glasses and starts smoking. He buys her pink satin dresses, jewellery and lingerie and photographs it all.

The relationship appears to come to an end just before Christmas in 1970 when reports and photographs of Margret begin to break off. According to Günther’s notes, she tells him that “after Christmas the f***ing will be over and you will not dance at two weddings anymore.”

He gets involved with other women at the request of Margret who wants him to go on dates with other women, presumably to quell suspicion from her own husband.

There is Giesela, who Günther describes as “sexually starving”, and Ursula, a “big and skinny” 21 year-old who “looks really good. White boots, green dress, black hair.” Günther reveals Margret’s subsequent panicked jealousy, begging him not to fall in love with Ursula. He also mentions that despite him still being involved with Ursula, Margret fights with her husband and asks for a divorce.

His last note is a long description of him and Margret making love. The story is left unfinished, fragmented, there can be no real happy ending.

And the questions linger. What makes a man document his affair so meticulously? Did he want to preserve the relationship to relive it later? Was this industrial businessman searching for a creative platform to express his love? Or merely the confirmation of his control over the situation, as he mastered the art of adultery?

The book ‘Margret: Chronik einer Affare – Mai 1969 bis Dezember 1970’, published in German in 2012 is now out-of-print. The White Columns Gallery exhibition in New York was the first presentation of ‘Margret’ in a non-German speaking context.