The term war hero doesn’t usually bring to mind images of it-girls or front page glamour shots…

But the ladies of the female section of the British Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) singlehandedly transformed the idea of what it meant to be a war hero. They were the glamour girls of the Second World War, but they were also unapologetic pioneers of female aviation and equal pay. Together, they became the first women to receive equal pay to their male counterparts.

The ATA was founded in 1938 to employ British civilian or former military pilots who weren’t fit to as fighter or bomber pilots in case of war. They would work as ferry pilots and deliver military airplanes from factories to the RAF (Royal Air Force) at the front lines.

Aviation had been the high-end leisurely sport of the interwar period and as such there were many trained commercial and civilian pilots around…amongst them some inspirational women.

Amy Johnson

The most popular aviatrix at the time (and would-be ATA girl) was Amy Johnson. She was the first woman to fly solo from Britain to Australia and broke several flying records during the 1930s, including the fastest flight from Britain to Moscow and Britain to Japan.

She was the poster girl of female aviation in interwar Britain (she tragically died in service of the ATA in 1941).

“Wendy” – Audrey Sale Barker

Another notorious future ATA pilot was Audrey Sale Barker (nicknamed Wendy after Peter Pan’s flying friend), who once flew her and a friend to South Africa to enjoy a winter holiday. They crashed and weren’t expected to have survived, until a Masai warrior showed up with a polite note written in lipstick asking to please come and fetch them.

Pauline Gower

But it was Pauline Gower, daughter of MP Robert Gower, who cleared the pathway for women in the ATA.

Pauline was an incredibly talented and experienced flyer. Before the war, she ran a joy-riding plane service that offered 5-minute plane rides to civilians and she was a commissioner in the Civil Air Guard. She carried a commercial “B” license (the third woman in the world to do so) and had over 2,000 hours of experience to her name, having safely flown and landed over 30,000 passengers. She convinced the higher ups at the ATA that they needed a female section of ferry pilots, and that she should be the one to establish it.

Gower (right) and her ATA pilots (c) CEB

The ATA initially asked Gower to set up a team of eight women pilots – a number that had come down from 15 after male members had protested the idea. They would transport Tiger Moths from factories outside London to Scotland and Northern England during winter. It was a thankless job that no one else was willing to take on. But these women took to it without hesitation.

Far more than men, women were required to have at least 500 hours of flying experience and they were only allowed to fly light training aircraft.

The idea of a woman flying an airplane was still something ludicrous to most men (and women) of the time. The male editor of aviating magazine Aeroplane, pretty much summed up the ruling sentiment when he wrote:

“We quite agree … that there are millions of women in the country who could do useful jobs in war. But the trouble is that so many of them insist on wanting to do jobs which they are quite incapable of doing. The menace is the woman who thinks that she ought to be flying in a high-speed bomber when she really has not the intelligence to scrub the floor of a hospital properly, or who wants to nose around as an Air Raid Warden and yet can’t cook her husband’s dinner.”

I imagine Pauline Gower responding to that with a heartfelt “Poppycock!”

She and her first eight pilots – Winifred Crossley, Margaret Cunnison, Margaret Fairweather, Mona Friedlander, Joan Hughes (the youngest pilot at 17 years old), Gabrielle Patterson, Rosemary Rees, and Marion Wilberforce – were dead set on proving the skeptics and haters wrong.

Pauline Gower with the original eight

And boy did they! Not only did the female A.T.A. section grow from 8 to 166, but they also went from solely flying Tiger Moths to flying 147 types of aircraft, including four-engine bombers that even intimidated male pilots.

Mary Wilkins Ellis, one of the later A.T.A. girls, said: “It was all so delightful, flying airplanes. I loved flying the fast and furious ones. I also liked flying the bombers.”

As trained pilots became scarce and military factories turned out more and more aircraft, the ATA designed its own training program. Girls from all walks of life – some of whom weren’t even old enough to drive cars – were admitted and trained at flying aircraft. They came with all kinds of different backgrounds: there were socialites, working girls, a skiing instructor, ballet dancer, mothers, a grandmother, a stunt-pilot, mathematician, architect, typist, actress, mapmaker and more.

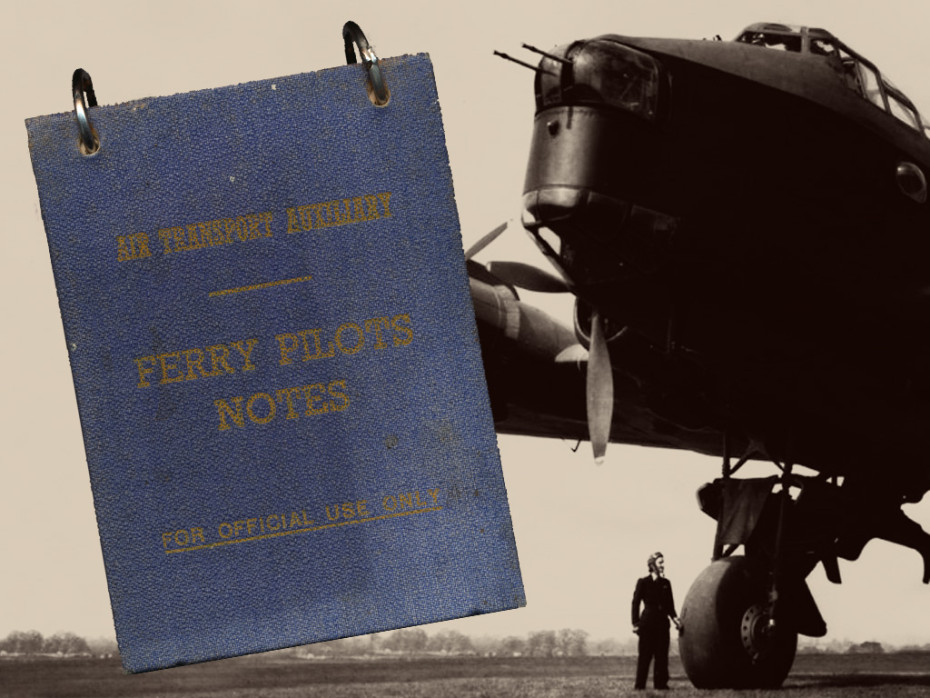

These women regularly flew several airplanes a day, and often they had never trained in the type they were about to pilot. All they had to guide them was a Ferry Note Book that enlisted all the specifics to each aircraft.

But there was one airplane that was loved by all ATA girls: the Spitfire. Light to the touch and incredibly sensitive, they quickly christened it the ultimate ladies plane. But that didn’t mean it was an easy aircraft to fly.

A Supermarine Spitfire fighter plane (AP Photo), a fleet pictured below.

A.T.A. girl Freydis Sharland recalls: “Gosh, it felt like someone had kicked me in the rear end and the next thing I knew was at a thousand feet! It was unlike anything we’d ever flown.”

There were some that preferred flying different aircraft: Margaret Frost claims she only liked the Tiger Moths. Annette Hill remembers being nicknamed “the Barracuda queen.”

But whatever type of aircraft they flew, it was never really safe. The cloudy British weather could be traitorous, especially while flying above the hilly landscape.

Pilots faced hypothermia and they had to navigate the balloon barrages – blimps tethered with metal cables meant to damage enemy aircraft in case of an air raid. On top of that, they flew without radios or ammunition and had to navigate their routes by eye, using only landmarks on the ground.

Many ATA members, male and female, lost friends and colleagues. In total, one in ten ATA pilots did not survive. On top of that, there were the casualties at the front. But despite the relentless death toll of the war, the girls always felt they had to continue their work without repine.

The hardships of the war did not stop the A.T.A. girls from enjoying their newfound freedom however. Some of the girls would travel to London every chance they got to meet bachelors and/or party the night away.

They’d work 12 days at an end and have two days off – those were to be enjoyed. Most ATA girls were young and clueless about boys and despite having many escorts, their encounters were innocent. But there were also those who vowed to sleep with every soldier they could lay there hands on.

ATA girls were incredibly popular and their uniform – dark blue skirt or trousers, a forage cap, black tie and single breasted jacket with an ATA insignia and gold threaded wings – were unlike anything most men (and women) had ever seen.

Leader of the it-girls, Diana Barnato Walker, would often head to London in the evenings, take the first morning train back to the ferry pool and get back to work. She was known to fix her lipstick before landing, never wanting to look anything but picture perfect.

Diana Barnato Walker

The British press was all over the ATA girls. They graced the covers of magazines and were the topic of many a wartime newspaper article or television item.

In an iconic cover of the Picture Post, Argentinian born Maureen Dunlop poses as a professional pinup girl. But according to her, she wasn’t interested in attention or glamour. In fact, the iconic picture was taken while she politely told the press she didn’t have time for them and brushed her hair out of her face to get on with work.

Maureen Dunlop Picture Post Cover

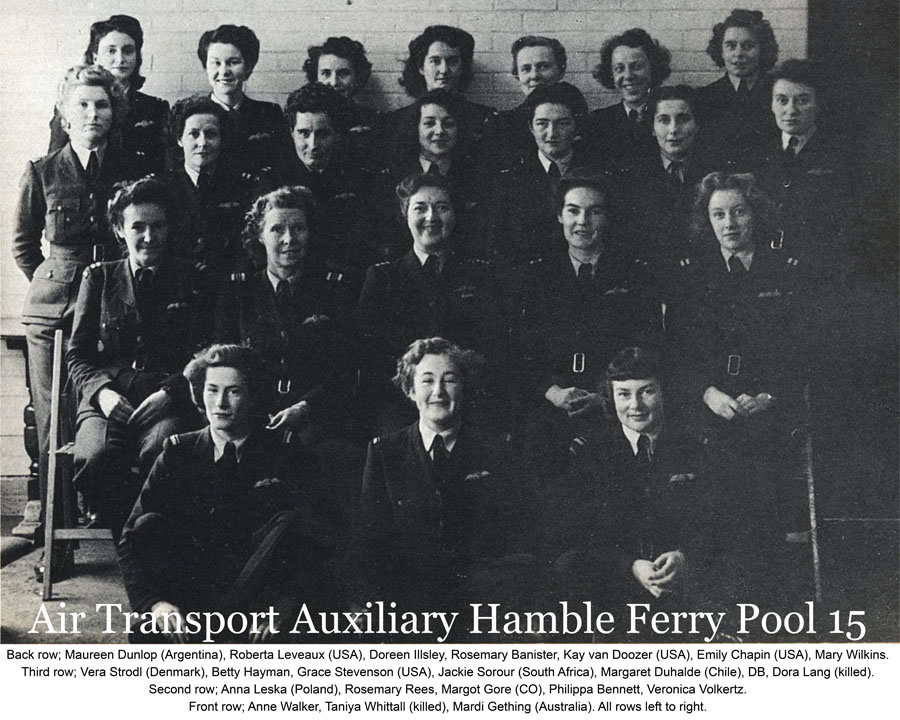

Maureen wasn’t the only foreign pilot in the ATA. Women from all over the world flocked to Britain to contribute to the war effort while enjoying the freedom of flying aircraft. Some of them came all the way from New Zealand and paid their own fare to the U.K. to do so. Others came from Chili, Poland, Canada, South Africa, the Netherlands and elsewhere.

Polish pilots Anna Leska, Jadwiga Pilsudska and Stefania Wojtulanis

Polish Pilot Stefania Wojtulanis

Chilian Pilot Margot Duhald

One of the more colorful characters to join the ATA from abroad was Jackie Cochran (pictured). She was an American born in poverty who married a billionaire and became a millionaire in her own right by launching a highly successful make-up chain. She was a huge fan of aviation and a truly pioneering aviatrix – often forgotten next to Amelia Earhart.

Cochran Hanging out with Male Pilots

As the war raged and more and more pilots were needed, Jackie Cochran joined the ATA with 25 American women. They would regularly bump heads with the Brits, who according to them were stuffy – and the Brits had a hard time getting used to the American’s informality. But no one was as verbal and informal as Jackie. Roberta Leveaux, one of the American pilots, says they were simultaneously “in awe of her and kind of embarrassed by her.”

The Brits meeting the Americans – obviously over a cuppa.

After a few months of observing how the Brits did it, Cochran flew back to America and established her own version of the ATA there.

In 1942 there were two women-only ferry pools: Hamble and White Waltham. According to Joy Lofthouse, the waiting rooms there would have made a fine television show. When the weather was cloudy (which was often) the girls would have to wait until the air cleared. There’d be women playing pool, bridge, backgammon, doing yoga and chattering in all different kinds of languages.

But they’d have to be ready to take off at any given moment. Even if that meant wiping off their wet nail polish.

The women worked just as hard as the men, but were paid over 20% less. This was something that Pauline Gower was unwilling to accept.

A charming and well-respected woman who always knew to ask the right questions to the right people, she instructed a female Tory MP friend to ask the aviation minister in the commons if it was “the case that henceforth women pilots will be paid the same as men.” She let him know that if the answer would be no, she wouldn’t stand for it. And so the answer was yes.

Female ATA pilots were the first ever to receive equal pay for equal work in British history.

But the bias of male colleagues was harder to overcome. Some flat out refused to fly with or be trained by women pilots.

Mary Wilkins Ellis (pictured above) remembers one incident where she delivered a Wellington bomber and everyone stood around waiting. When she asked if she’d be taken to the control, they said they were waiting for the pilot. When she told them that she was the pilot, they didn’t believe that a little girl like her would be capable of flying a bomber and they searched the cockpit – only to be shut down by the fact that there was no one else there.

During the war, the ATA delivered over 308,000 aircraft of 140 types to the R.A.F., playing a fundamental role in the war effort.

Unfortunately, the end of the war also meant the end of newfound freedom for most women ATA pilots. The female ATA section dissolved quickly after the war and only a few continued to be successful in their piloting career. They continuously faced resistance from their male counterparts and even the former ATA pilot who became the first female commercial pilot, Jackie Sorour, was only allowed to fly from Bristol to the Channel Islands and was continuously mistaken for a stewardess.

To most ATA girls, their short time as ferry pilots could be described as the best time of their lives.

ATA pilot Joy Lofthouse; then ↑ and now ↓

Some were unwilling to say goodbye to the life they experienced: Joy Lofthouse recently flew a Spitfire again at age 92. She said of her years with the ATA: “I was so wicked, I never wanted to war to end, so I could go on and on and on!”

Inge Oosterhoff is a Dutch graduate of North American Studies, currently living in the Netherlands. With a love for the odd and the unexpected she is on a never-ending search for new stories, new people and the very best coffee in the world.

Inge Oosterhoff is a Dutch graduate of North American Studies, currently living in the Netherlands. With a love for the odd and the unexpected she is on a never-ending search for new stories, new people and the very best coffee in the world.