It does sometimes seem like our early 20th century ancestors had a knack for coming up with particularly extravagant new ways to torture themselves. An electric bath? Sounds pretty awful, doesn’t it? Fortunately it didn’t exactly involve mixing a bubble bath with electricity and taking a dip after a long day. In fact, this turn of the century invention really isn’t all that far from what we know as the modern day sun bed. Yes, the very same instrument we’re still torturing ourselves with more than 100 years later…

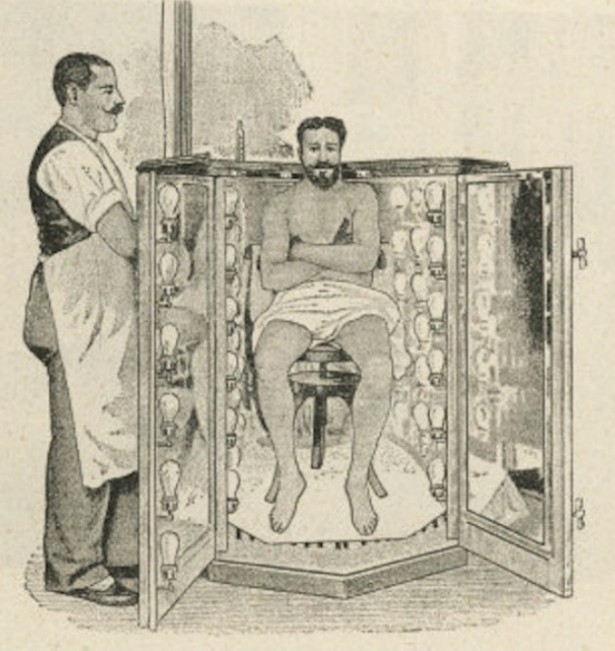

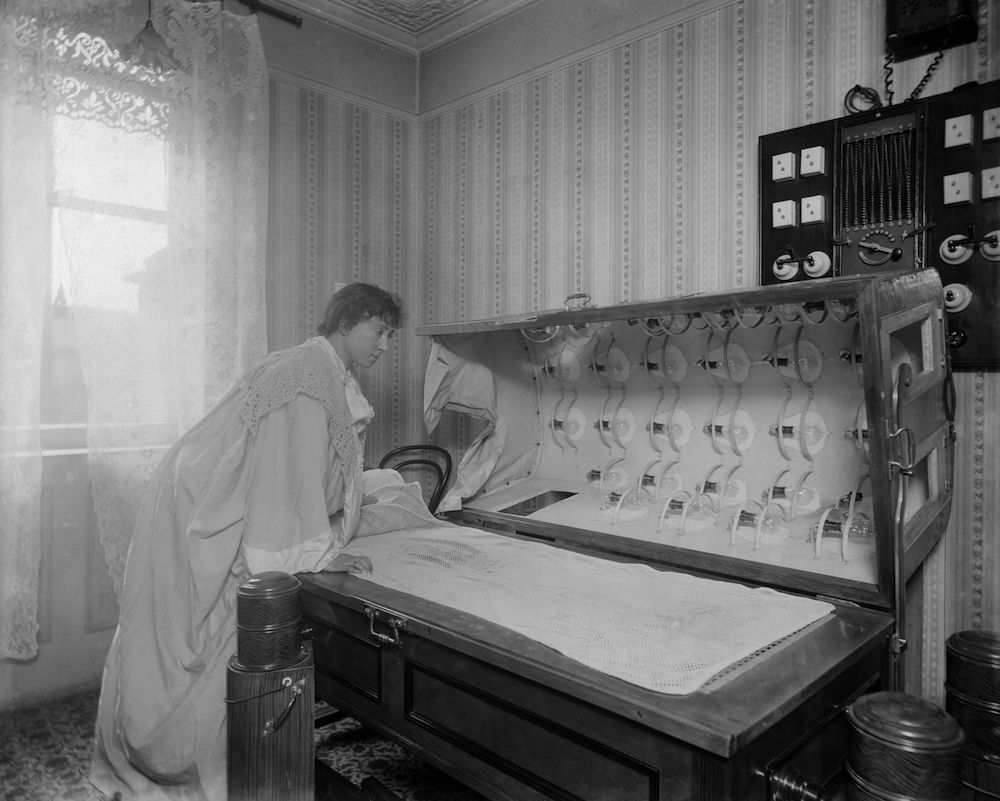

Used primarily for medical reasons, light therapy became popular particularly in Europe at the dawn of the 20th century until the late 1940s. Just like the sun bed industry today, people could either buy these oversized units for their own own or simply pop into a local “Light Care” institute. Hospitals also began opening departments that offered electric baths as a free service to treat acute and chronic diseases.

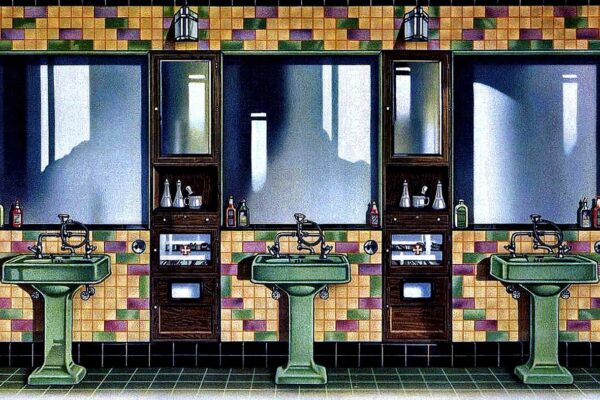

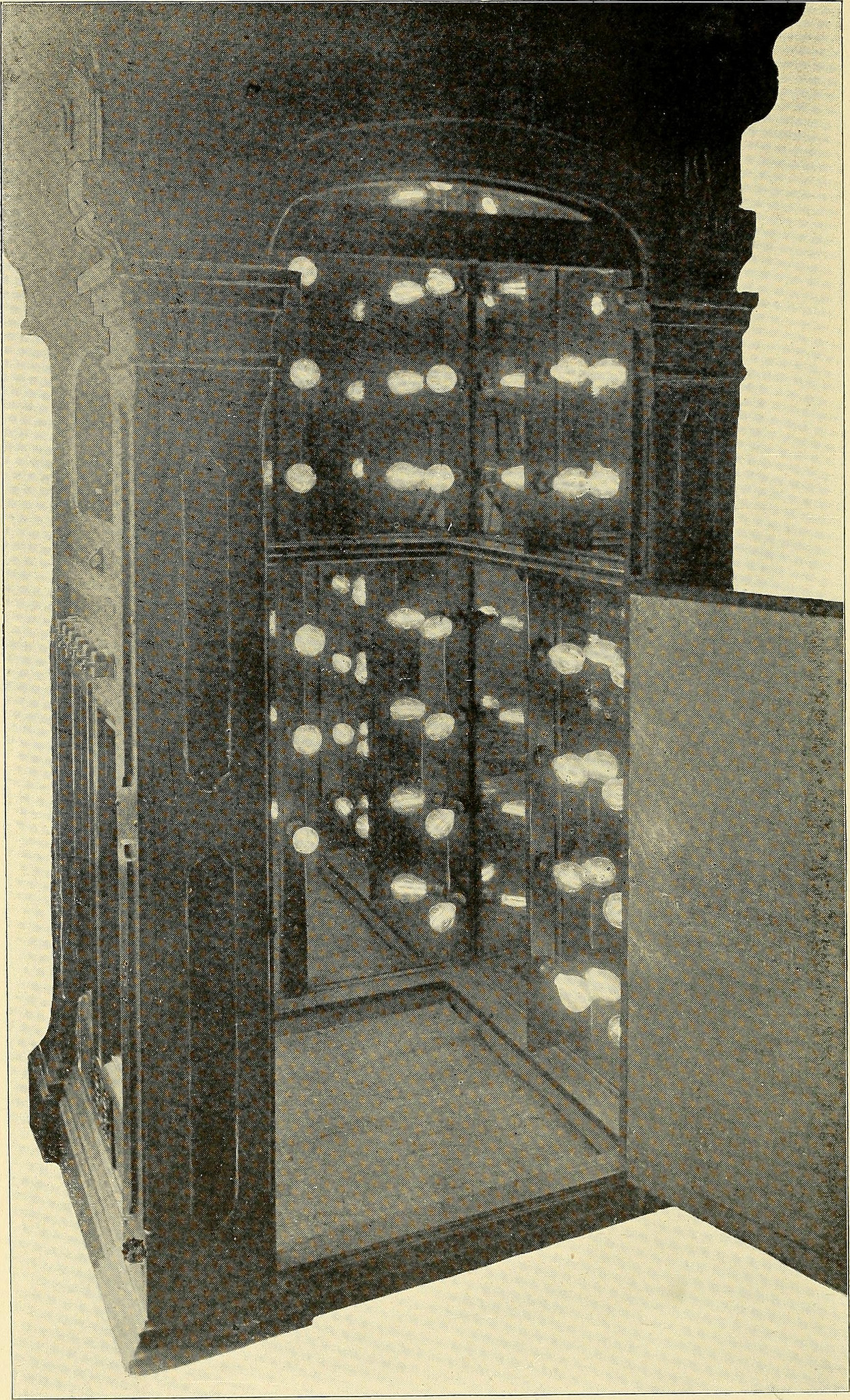

↑ This is the electric bath aboard the Titanic in 1912.

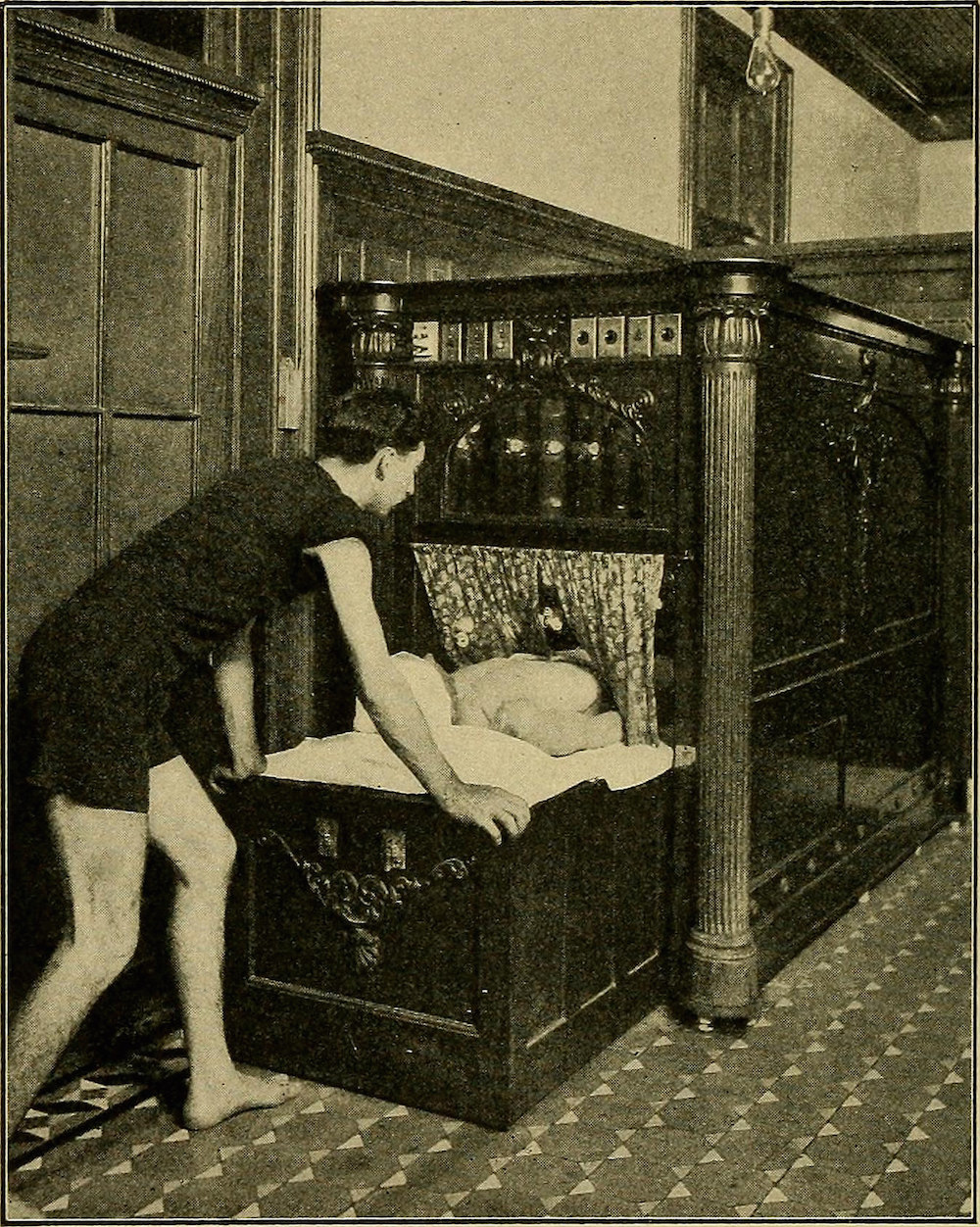

An antique electric bath at the Kellogg Discovery centre in Michigan

This electric bath was made by Harvey Kellogg– yep, the very same guy that invented Corn Flakes. The New York Times actually credited Harvey with inventing the electric bath, soon after his friend Thomas Edison had perfected the lightbulb.

From the late 1870s, Kellogg ran a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan which focused on using holistic methods, but was also full of inventions that promised health and wellness. In a book he wrote on the subject in 1910, Harvey wrote:

From the late 1870s, Kellogg ran a sanitarium in Battle Creek, Michigan which focused on using holistic methods, but was also full of inventions that promised health and wellness. In a book he wrote on the subject in 1910, Harvey wrote:

“The electric-light bath prolonged to the extent of producing vigorous perspiration should be employed two or three times a week. Tanning the whole surface of the body means of the arc light will be an excellent means of improving the patient’s general vital condition.”

So just to clarify, the same guy who invented Corn Flakes invented the tanning bed. Huh.

And speaking of Corn Flakes– an interesting if not slightly disturbing side note on how Kellogg invented them:

The American medical doctor and strong advocate of vegetarianism strongly believed that masturbation was the worst evil one could commit and often referred to it as “self-abuse”. He insisted that diet played a huge role in masturbation and that a bland diet would decrease excitability and prevent masturbation. Thus, Harvey Kellogg, leader of the anti-masturbation movement (and future inventor of the tanning bed), invented Corn Flakes breakfast cereal in 1878. He hoped that feeding children his plain cereal every morning would help to combat the urges of “self-abuse”.

The American medical doctor and strong advocate of vegetarianism strongly believed that masturbation was the worst evil one could commit and often referred to it as “self-abuse”. He insisted that diet played a huge role in masturbation and that a bland diet would decrease excitability and prevent masturbation. Thus, Harvey Kellogg, leader of the anti-masturbation movement (and future inventor of the tanning bed), invented Corn Flakes breakfast cereal in 1878. He hoped that feeding children his plain cereal every morning would help to combat the urges of “self-abuse”.

Enjoying a bowl of Corn Flakes will never be the same again.

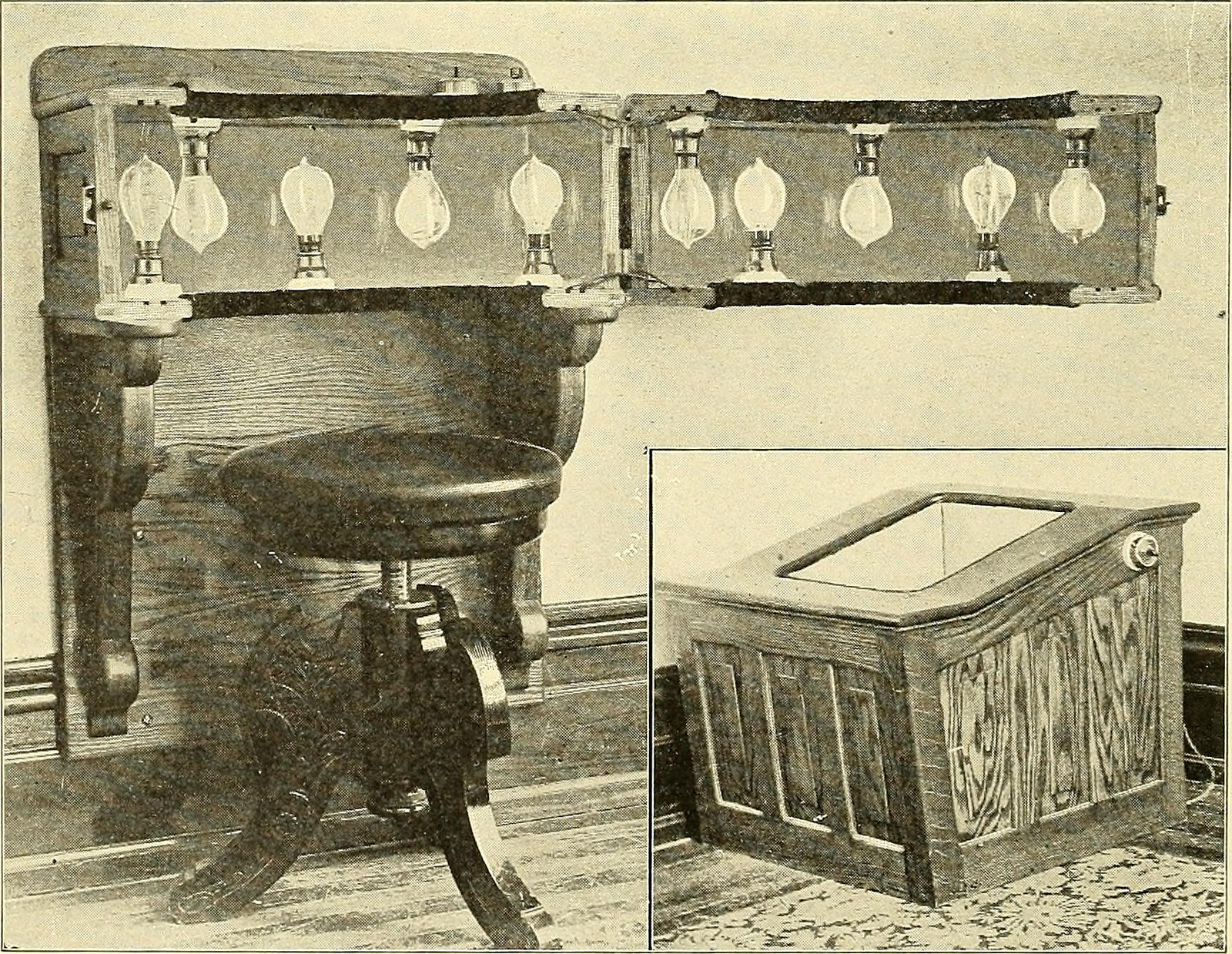

So did these electric baths, that apparently came in a wide range of shapes and sizes, actually treat illness?

Natural or artificially-produced sunlight, used all over the body or just locally on a specific area such as a wound, was understood to be a powerful natural regenerative agent. In the 1890s, ultra-violet was “discovered to have a powerful anti-bacterial action” and in 1903 a Dane, Neils Finsen, was awarded the Nobel Prize for his work in treating skin tuberculosis with ultra-violet light.

Clinics offering sun therapy began popping up in the Swiss Alps and around Europe to treat patients with TB, wheeling them out onto large sundecks for long periods of the day. Major hospitals began using ‘sun-lamps’ to treat circulatory diseases, anaemia, varicose veins, heart disease and degenerative disorders. In the early 1940s, Doctor Emmitt Knott began administering light to the whole body by irradiating a small volume of blood. He found it made a dramatic impact in the treatment of sepsis, polio and herpes. By 1947, “somewhere in the region of 80 000 patients had been treated with reported success rates of 50-80%”.

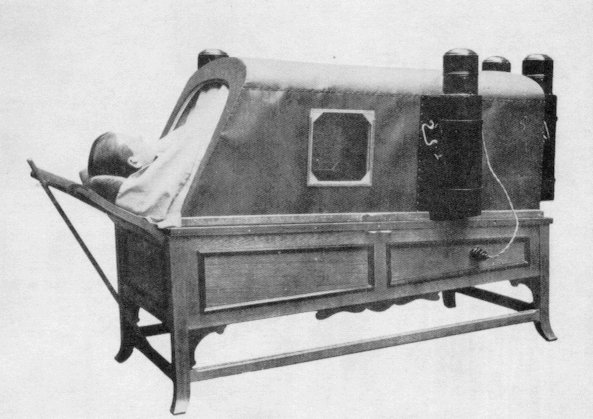

Electric Light Bath Cabinet, at the Kellogg Discovery Center

The light therapy business was booming. The special lamps and devices for the electric bath was a fast-growing market. But even back in the 1920s, at its height of acceptance in the medical community, there were reports that ultraviolet light could cause skin cancer.

While a craze of ultraviolet overexposure was having a potentially fatal effect on the public, only a handful of anxious physicians were willing to investigate the booming business.

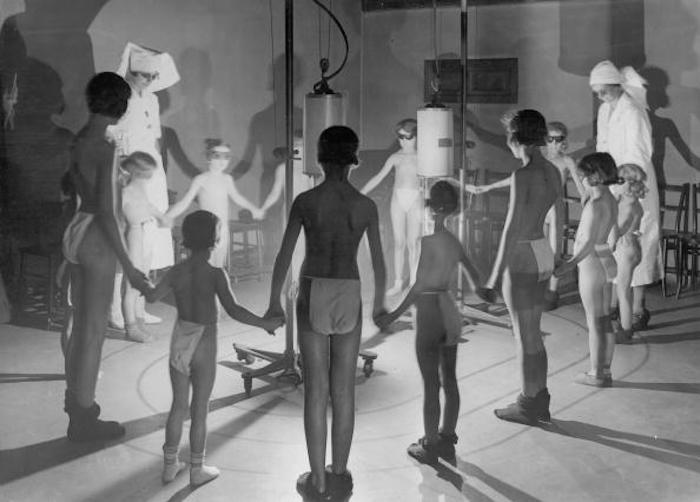

One such physician was Dora Colebrook, who was particularly interested in studying the medical community’s obsession with using light therapy in the treatment of ‘weedy’ or ‘sickly’ children and varicose ulcers. She went as far as conducting a study on 287 schoolchildren (unbelievably, with their parental consent).

Miriam Price Coleman day nursery, 1938 (c) Fox & Getty

She was unable to find any beneficial effects of light therapy, detecting no change in weight, height or duration of colds and no improvement in minor infections, nor their overall wellbeing.

The Institution of Radiotherapy, 1934

Colebrook’s unwelcome study was not surprisingly opposed by the medical community, claiming her ‘scientific’ method was “no match for the accumulated experience and wisdom of eminent physicians”. Even the press got involved, and newspapers such as the Times and the Guardian wrote critical editorials in the 1920s of her study, arguing that “the long and distinguished pedigree of light therapy proved its value”.

I remember quite recently in fact, my own father telling me that his doctor had recommended occasional visits to the sun bed to help with his symptoms of fatigue, just as they used sun lamps in hospitals of the 1930s to treat anaemia. Tanning salons still pepper the local high street– so just how far have we really come from an era of doctors recommending ultraviolet exposure and Victorian electric baths?!