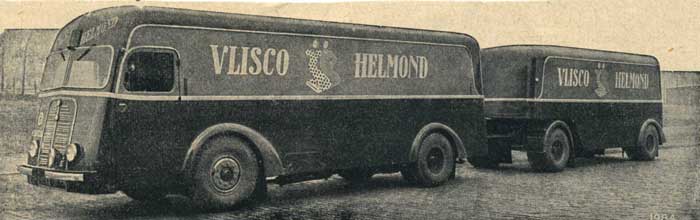

A small town factory in the Netherlands might not seem like the obvious birthplace for African haute couture. Helmond is a place most people (Dutch or African) wouldn’t be able to point out on a map and yet, this unassuming little town is where one of the most iconic fashion brands of West and Central Africa was created. As the main supplier of fashion prints to nearly half a continent, the textile company has continued to dominate that fashion scene there for almost 170 years. How’d that happen? Rooted in European colonialism and a testament to African ingenuity, creativity, and cultural pride; it’s a surprising story…

Vlisco hadn’t meant to become the main supplier of wax print fashion fabrics to West and Central Africa. In fact it’s almost by accident that they did. They originally had their eye on an entirely different market– Indonesia.

Vlisco hadn’t meant to become the main supplier of wax print fashion fabrics to West and Central Africa. In fact it’s almost by accident that they did. They originally had their eye on an entirely different market– Indonesia.

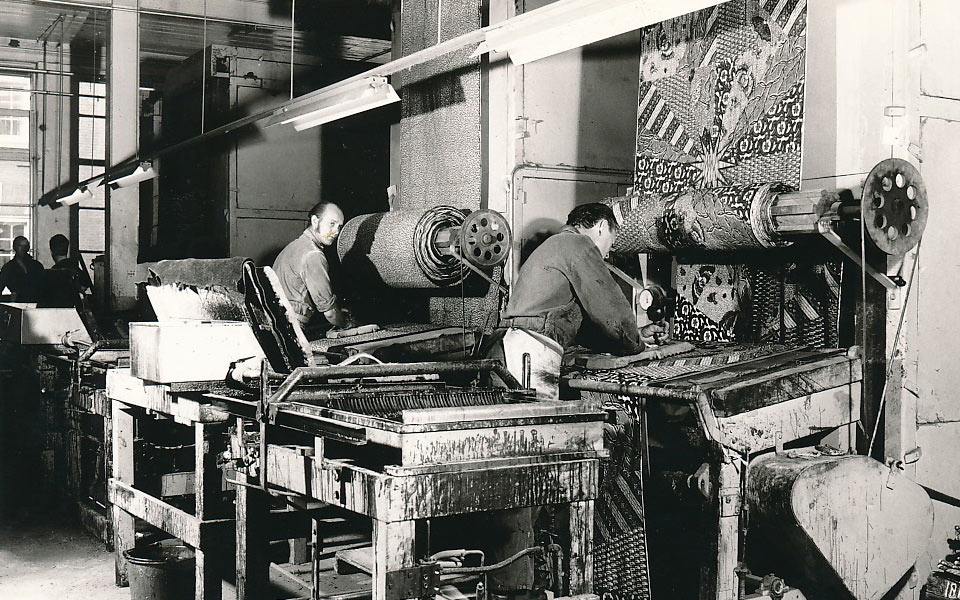

We go all the way back to 1864, when Amsterdam entrepreneur Pieter Fentener van Vlissingen took over a small textile-press company in Helmond. Pieter’s uncle, who worked in the former Dutch East Indian colonies, convinced his nephew to produce a knock-off version of a traditional Indonesian textile known as Batik.

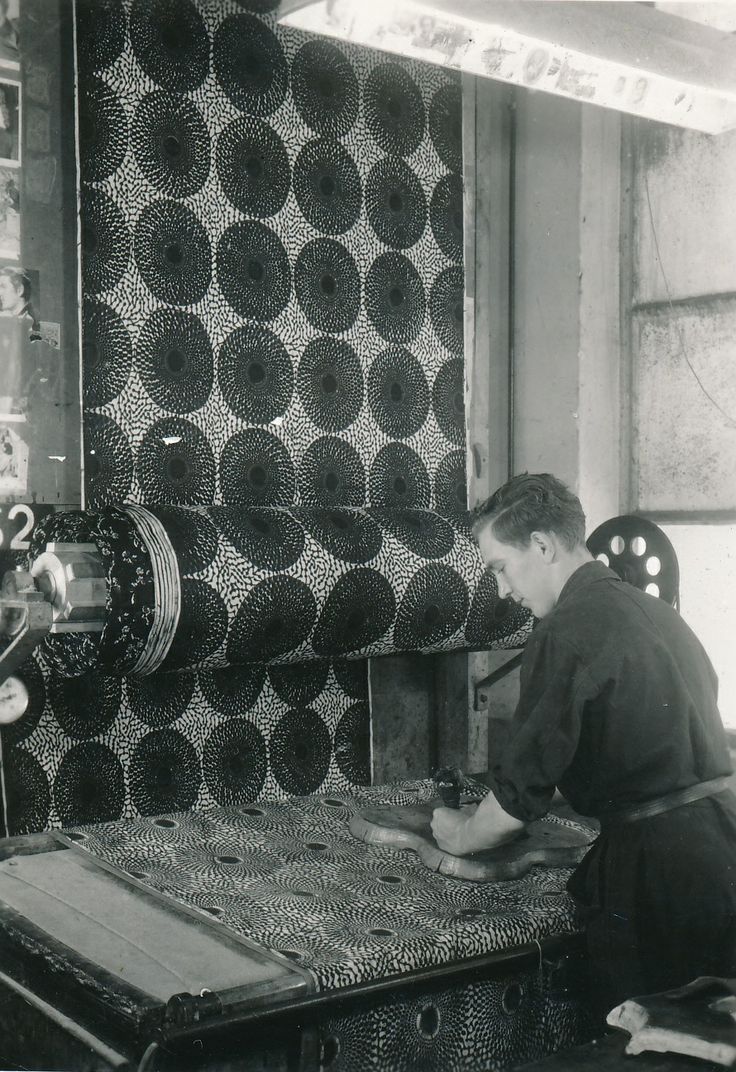

The ancient Batik technique of wax-resist dyeing applied to whole cloth takes a long time to produce, but Pieter and his uncle used a few tricks to mass produce their Batik fabrics, which they thought would sell well in the Dutch East Indies.

Indonesians were unimpressed however – it may have been cheaper than the handcrafted original, but it also looked like it. The mass-producing aggravated the craquelé-effect, which was seen as an imperfection.

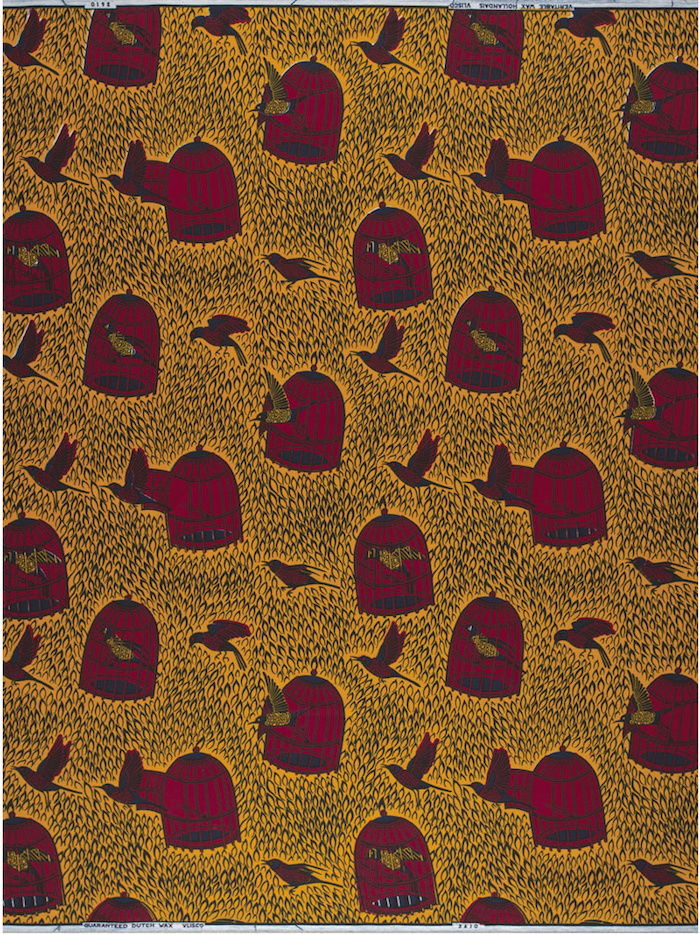

West and Central African buyers preferred these imperfections however, because it meant that no one piece of fabric was the same. Moreover, the double-sided printing was perfect for traditional wrapped fashion styles.

Ships transporting Vlisco products to Indonesia had already been making stops around Africa to trade some of the fabric for food and other essentials for the travel ahead. There, the wax print fabrics were not a cheap copy of a local original, but a unique luxury item that today has come be referred to as the “Chanel of Africa”.

Having failed to make a mark in Indonesia, Vlisco was quick to move in on the African market potential, changing their product to satisfy local requests for bold colors and prints and becoming the first Dutch fabric factory to hire their own design team in 1894.

By 1930, Vlisco was one of the top luxury fashion brands in West and Central Africa, and they currently distribute to a 400 million market spread out primarily over the Ivory Coast, Nigeria, Togo, Benin, Ghana, and Congo.

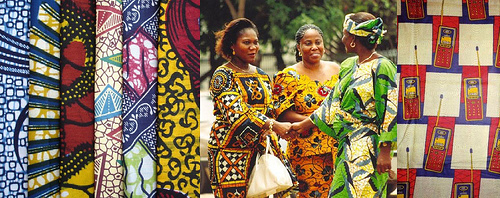

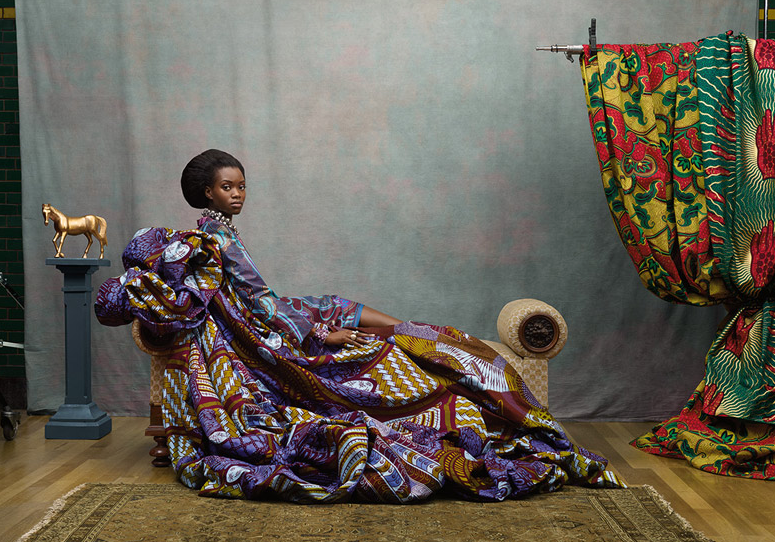

But while it was Coco who put haute couture in Chanel, it is the African ladies who put high fashion into Vlisco. Celebrating individuality through fashion, they take the fabrics to local designers and dressmakers to create their own uniquely personal couture.

But while it was Coco who put haute couture in Chanel, it is the African ladies who put high fashion into Vlisco. Celebrating individuality through fashion, they take the fabrics to local designers and dressmakers to create their own uniquely personal couture.

And these outfits don’t just celebrate the women’s individual style. The fabrics themselves are assigned names and meaning to communicate information about the women that wear them – meanings that are not assigned as a marketing trick by the producers, but that are created by the women who sell and wear the fabrics.

Local saleswomen attributed names and stories to the fabrics (which are only given numbers by the factory) to promote and better sell their product. They gave the prints local and cultural meaning, truly embedding the brand into the local culture. But the meaning given to some prints also provided a way for the wearer to communicate something about herself.

A century ago, this was a way to circumvent illiteracy and the lack of women’s freedom to speak out, but today these fabrics can still send some pretty powerful messages – some of which express more than a little bit of girl power!

From the 300.000 prints that the Vlisco archive holds, a few continue to be bestsellers…

One of those is the print below, titled “Si tu sors, je sors” translating to “if you go, I go.” Wearing this print tells men that “if you think marriage is something you can take and leave as you please, I will do the same.”

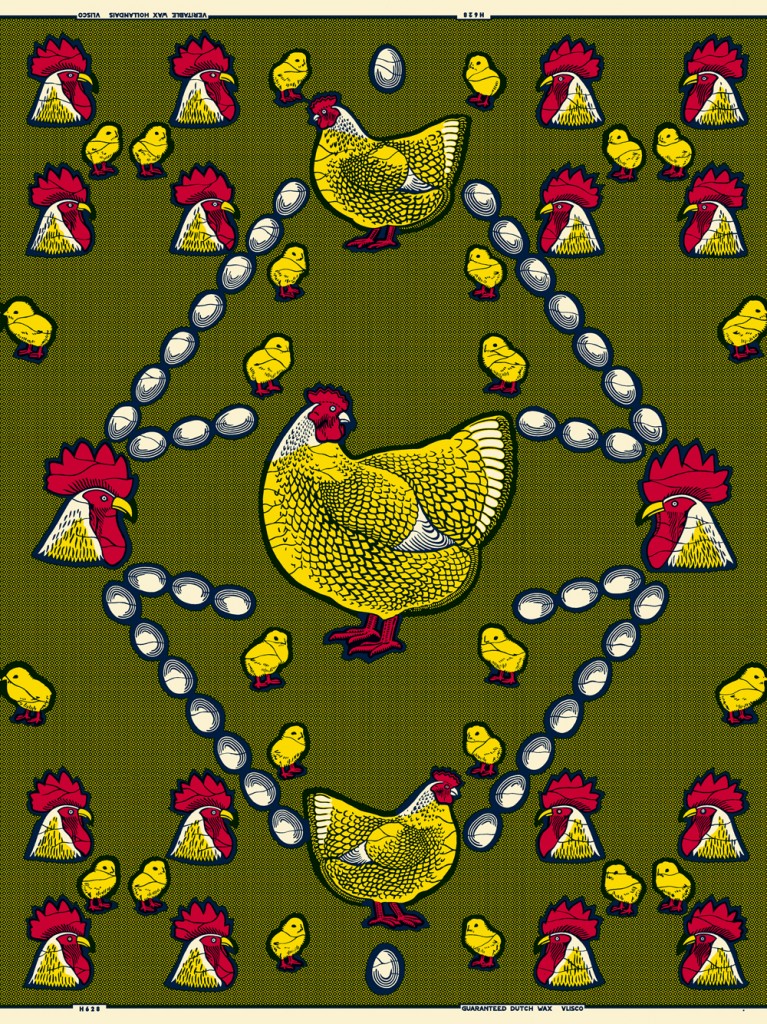

Another print, with a chicken, chicks, and a headless rooster – nicknamed “La Famille”- hints that the wearer may have a husband, but that she’s the true center (or head) of the family (or in some regions, that he’s physically useless…)

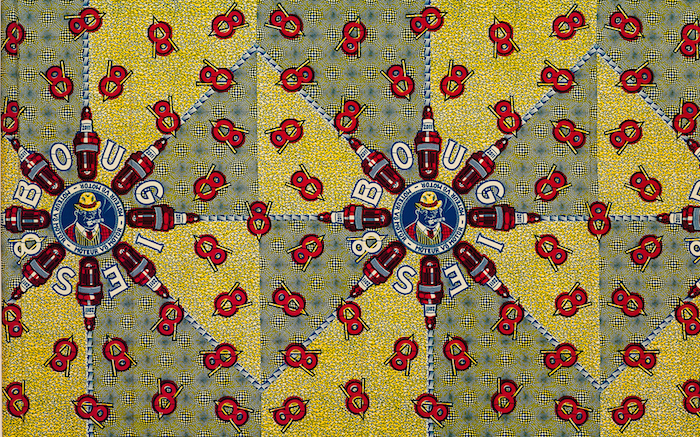

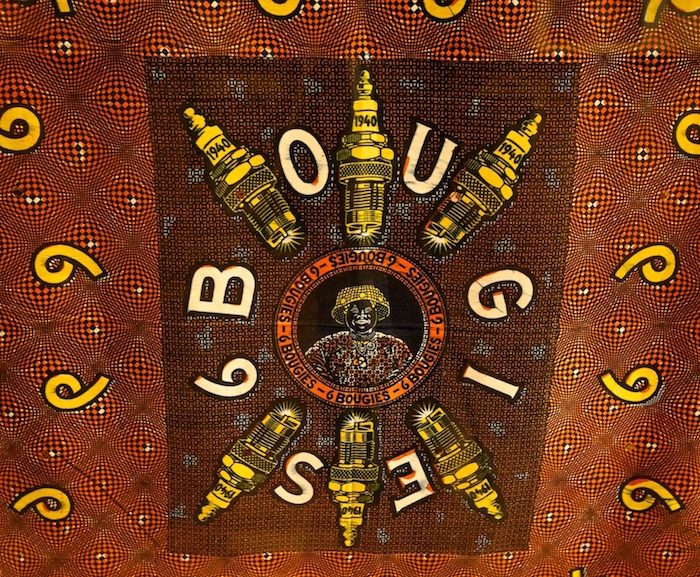

A print designed in 1940 called Six Bougies, changed meaning over time. At first, it signaled economic prosperity, as the owner demonstrated that he or she could afford a six cilinder car. But the print eventually took on a quite different meaning: that the woman wearing had the umph to handle six men – a meaning repurposed for the next generation design of Eight Bougies…

A woman who takes special pride in her education might wear a print called “ABC” which features chalkboards, measuring sticks and books.

Meaning of Vlisco fabrics is also locally decided. This fan print, for example, signifies in some parts of West-Africa that the wearer can dance the cha cha cha.

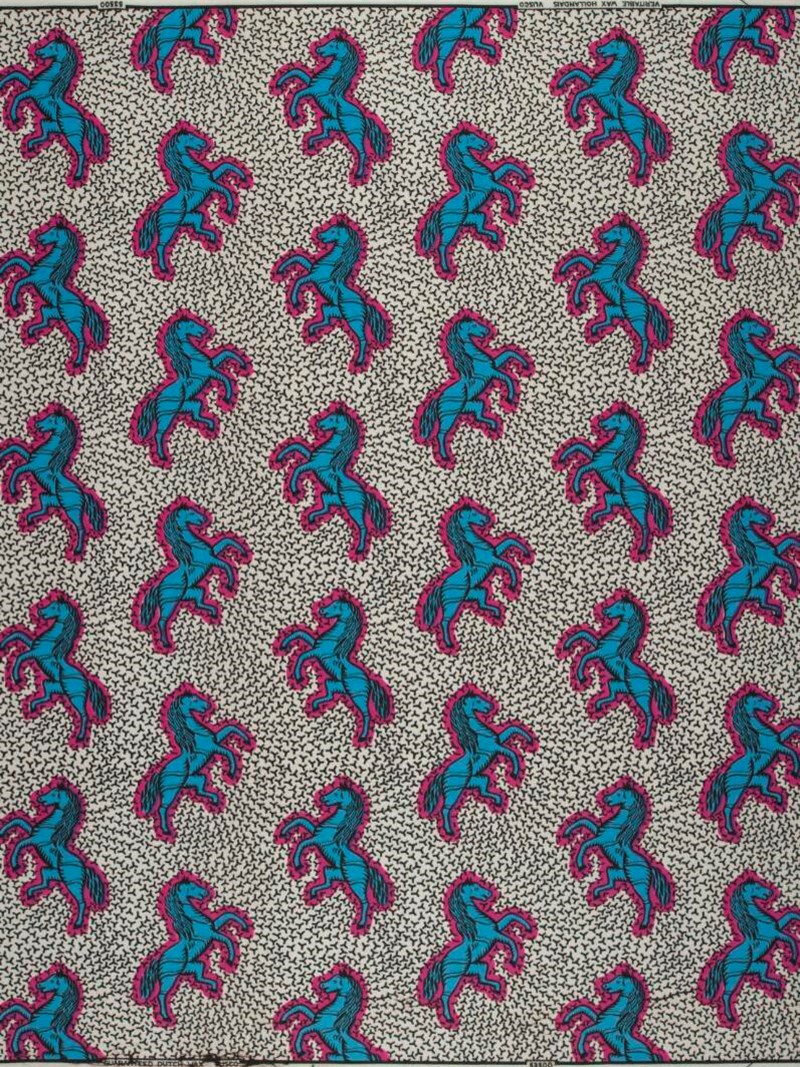

The design of a rearing horse is traditionally worn by Igbo women in Nigeria at the women’s meeting in August. In the Ivory Coast, it is called “Je cours plus vite que ma rivale” (I run faster than my rival) and signifies the rivalry between wives – the horses symbolizing horses in race.

New prints also take on meaning through current events, or are worn to remember moments of national pride. The fabric called “Michelle Obama’s Handbag” was given this name after Michelle Obama visited Ghana. Not that the print was modeled after the handbag worn by the first lady, but the national pride of having the Obama’s visit influenced the meaning of the print.

The print below is most popular in Ghana and is nicknamed Kofi Annan’s Brain – a name it received to honor the speech that the Ghanaian diplomat gave in New York City on the day the new print was launched.

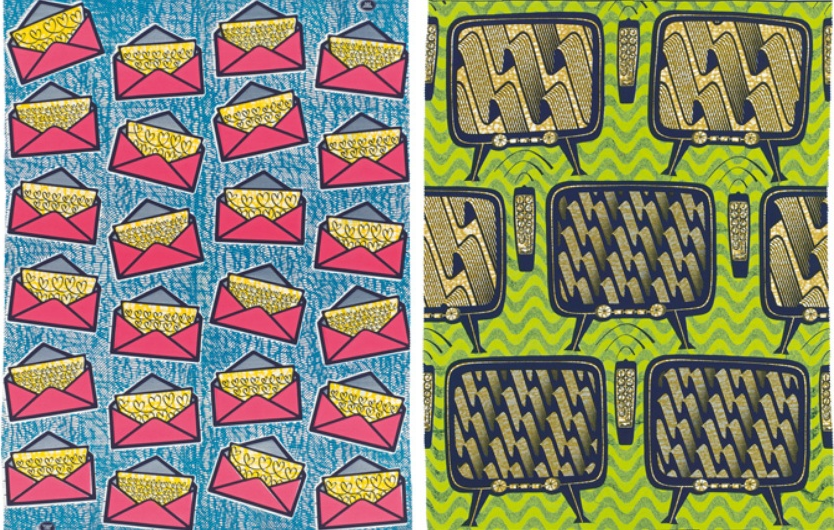

And you can always wear the colorful fabrics to showcase your profession, preferences, income, or hobbies, with prints ranging from ipods and laptops to televisions, cameras, high heels, roller skates, busses, clocks and more.

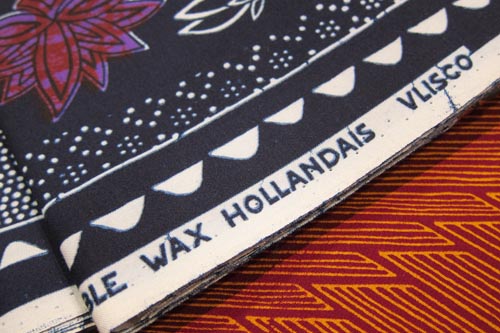

Quite ironically, Vlisco – having started out as a producer of cheap copies of Batik – was almost done in by cheap copies from Asia that flooded the market in the 1990s. Some ladies purposely left the edge of the fabric with the printed “Guaranteed Dutch Wax Vlisco” exposed in their dresses, to show that they were wearing the original.

To save itself from going bankrupt from cheap competition, Vlisco was bought by British investment group Actis, and set up an elaborate new business plan to relaunch itself from fabric factory to a full-fledged fashion brand.

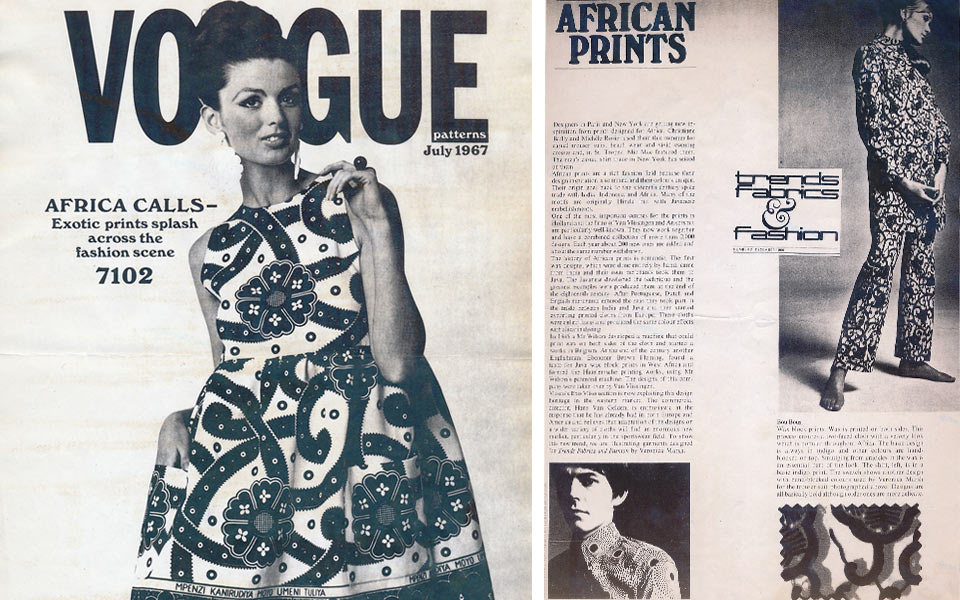

This included luxurious inspirational fashion shoots, launching new prints each season, increased on-the-ground production and promotion, local fashion shows, and more – an approach that saw Vlisco’s profit rise with almost 50 percent from 2010 to 2012.

In recent years, Vlisco has emphasized its high end market position by collaborating with young fashion designers (including myself when I still studied fashion design ⇒). Their fabrics have also featured in collections by established fashion designers like Junya Watanabe, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Dries van Noten.

Vlisco exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in Arnhem, 2012.

Vlisco also began catering to the Western market, currently working on a ready-to-wear collection and launching recent collaboration projects with Adidas, Eastpak, and Woolrich.

Parka’s by Woolrich and Vlisco

But Vlisco has also been putting more effort into honouring the ways in which their West- and Central-African costumers have embraced the brand for almost 170 years.

Vlisco recently launched multiple online oral history projects, setting out to collect stories about the local meaning given to their fabrics, the way their product has played a role in the lives of African women over generations and honoring the way local sales(wo)men have embraced, sold, and promoted their fabrics. You can find more on these projects here. The fashionable African youth is digging it too, creating their own fashion take on the fabrics that have been worn by many generations before them.

Inge Oosterhoff is a Dutch graduate of North American Studies, currently living in the Netherlands. With a love for the odd and the unexpected she is on a never-ending search for new stories, new people and the very best coffee in the world.

Inge Oosterhoff is a Dutch graduate of North American Studies, currently living in the Netherlands. With a love for the odd and the unexpected she is on a never-ending search for new stories, new people and the very best coffee in the world.