It’s at times of great inhumanity that you can find the greatest examples of humanity, if you look closely enough. During WW2, the Warsaw Zoo provided shelter to over 200 Jews who sought refuge from the horrors of the Holocaust. Several families were hosted in the residential villa of the zoo’s owners, and temporary hiding-places were created in empty animal-shelters. This relatively unknown WW2 history has been carefully recollected by the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, and I feel it is a story worth sharing again here.

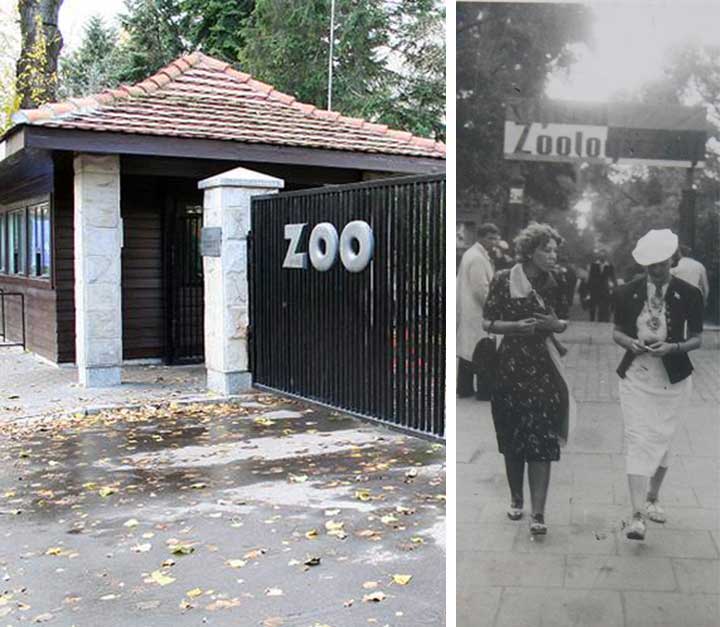

It all starts with Jan Żabiński and his wife Antonina. Jan became director of the Warsaw zoological garden in 1929, when the zoo had already evolved from a traveling animal exhibition in 1871 to a thriving zoological garden at the right bank of the Vistula River, where it is currently still located.

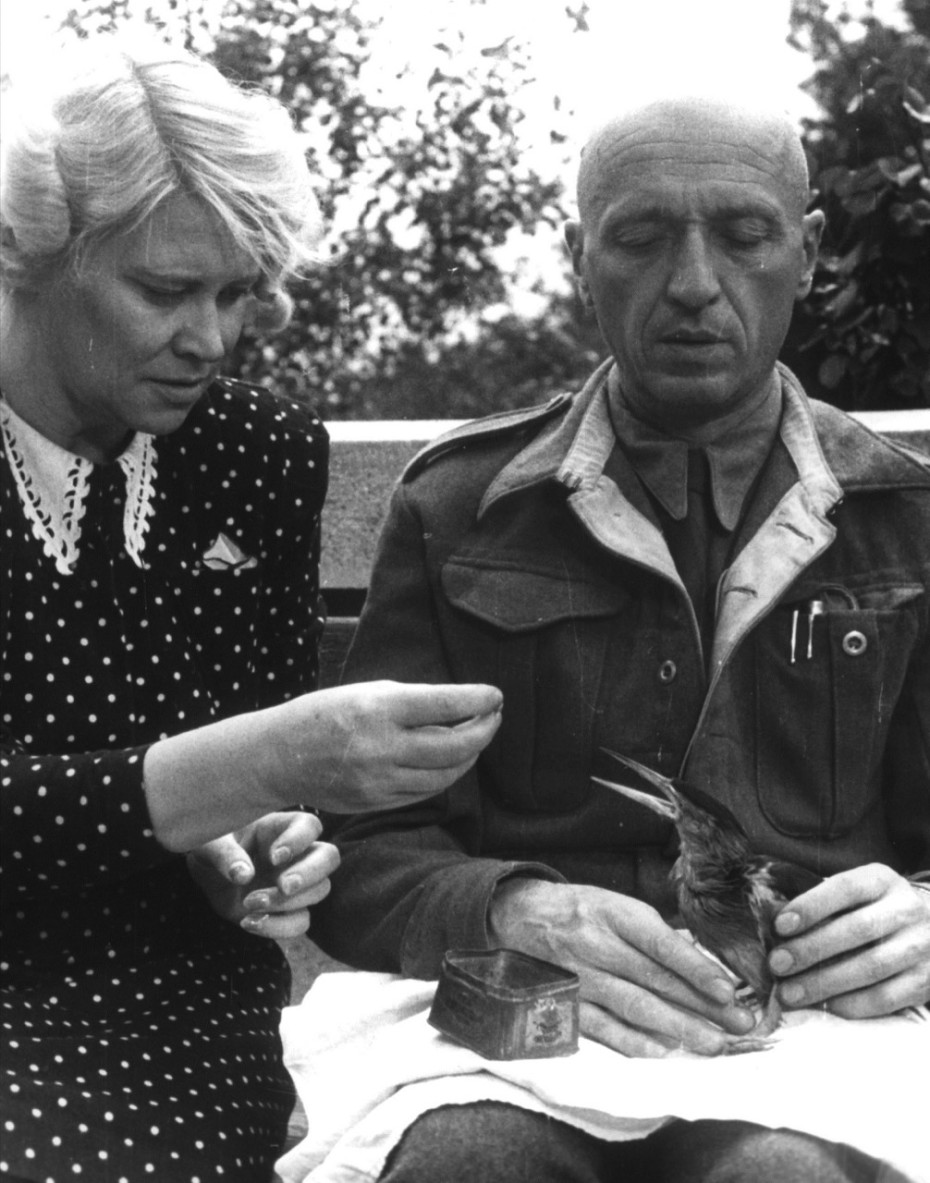

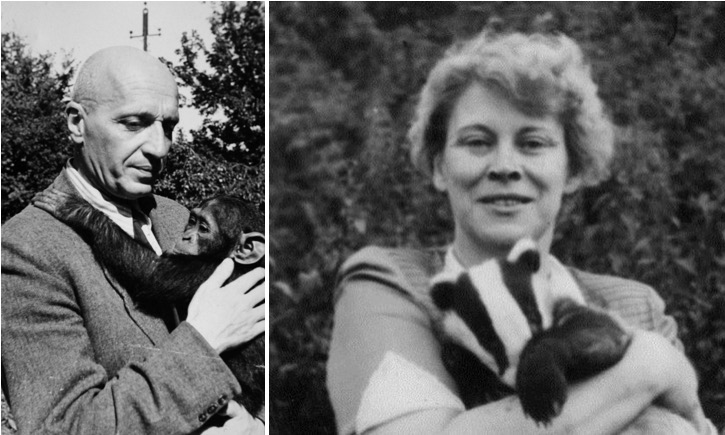

Antonina and Jan Żabiński

Antonina and Jan Żabiński

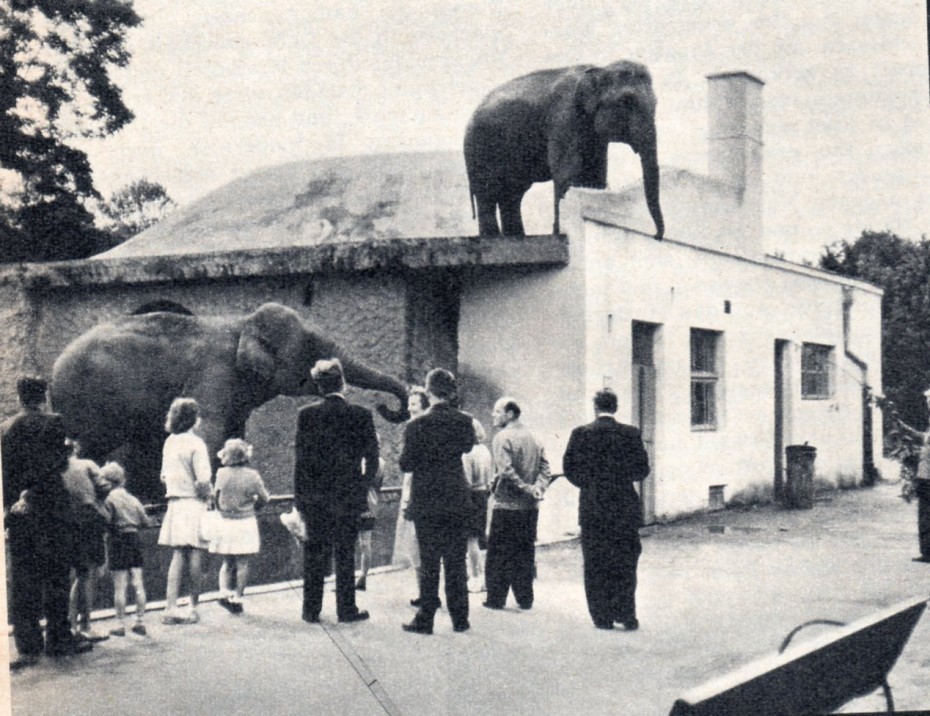

The zoo’s large collection of exotic animals and successful breeding program attracted visitors from all over the country. Especially when, in 1937, the zoo introduced the first Polish-born elephant – Tuzinka.

Tuzinka and caretaker

Jan and Antonina were great lovers of art as well as animals: Jan had studied drawing at the School of Fine Arts and worked as a researcher at the Warsaw University of Life Sciences, at the Department of Zoology and Animal Physiology. Antonina was an archivist at the same department, which is where they met.

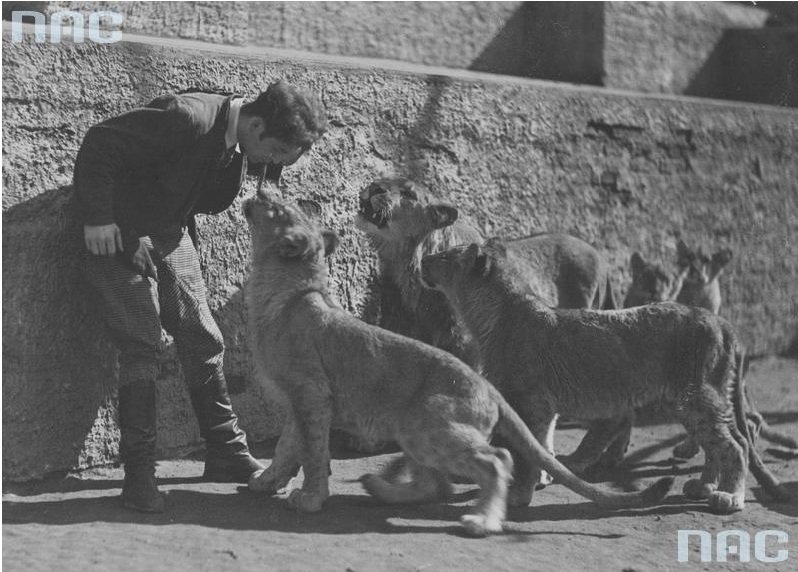

K. Lasocki painting lions at the Warsaw ZOO, 1937. (C): National Digital Archive

The zoo’s owners kept in close touch with the local creative community. They opened the zoo up to many artist and musicians, who would come there to work, get inspired, or give concerts in the open air. The colorful guests and the social activism of the Jan and Antonina, soon earned their residential villa the nickname “the house under a wacky star.”

Jan and Antonia regularly nursed several injured and sick animals to health in the privacy of their own home, including lynxes, a badger, a muskrat, cockatoos, piglets, and more. Jan used to say about this: “It is not enough to research animals at a safe distance – you need to live with them to truly understand their habits and psychology.”

The zoo was thriving right up until the Second World War, when the German army invaded Poland in 1939. The bombing of Warsaw on September 1 also hit the zoo, killing many animals and urging Jan Żabiński to kill off all the predatory animals that might escape and roam the streets in subsequent bombings.

Bombed Elephant Shelter (c) Warsaw Zoological Garden

The remaining animals faced a sorry fate: the German army organized a spontaneous hunt at the zoo, shooting any animal they deemed “not valuable.” Those animals that were considered “valuable” were captured and transported to the Schorfheide reserve, close to Berlin, at the border with Poland. (As it happens, Nazi’s regularly used this nature reserve as a private hunting ground). Tuzinka the elephant was taken to the zoo in Köningsberg.

Adolf Hitler and Hermann Göring at the Schorfheide Reserve

The animals that were left after all this became a food source for Warsaw locals and the army during the siege of the city. It was horrible for the Żabińskis to witness and decide on the death of their beloved animals, but the war left them little choice. Antonina Żabińska wrote of this time in her memoires: “There was this gloomy, dead calm everywhere, and I kept telling myself that it is not the dream of death and extinction, but merely ‘winter sleep’.”

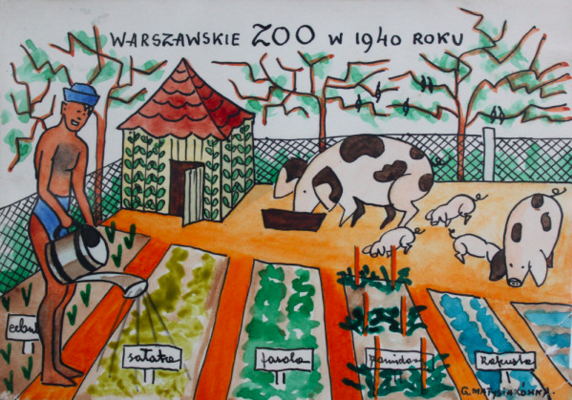

Child’s drawing of the Zoo in 1940 (c) Warsaw Zoological Garden

But all the misfortune did not stop Jan and Antonina from fighting back and using their position to help others.

Jan Żabiński had been involved in subversive activism before the war and continued this after Germany had besieged Poland. The German army had appointed him superintendent of Warsaw’s public parks, which provided him with a perfect opportunity to aid the Jewish community.

Jan talked the army into allowing him access into the Jewish ghettos to seemingly take care of the greenery there – of which there practically was none. The situation in the ghettos was dire – between 1940 and mid-1942, over 83,000 people died of starvation and disease. Not to mention the deportations and the killing of Jews inside the ghettos themselves.

Jan used his access to the ghettos as an opportunity to stay connected with his Jewish friends and colleagues, bringing them food and messages. He began breeding pigs in the abandoned zoo and smuggled the meat into the ghetto-walls.

He also provided several people with false documents and organised hideouts on the “Aryan” side of the city. The now empty cages of the zoo were used as temporary shelter for people until they could leave for other arranged hideouts.

Jan, Antonina, and their son Ryszard also opened up their own home to Jewish individuals and families seeking a place to hide – they never turned anybody down.

The Żabiński villa, still open to the public today

Jan would find people in need and bring them to the zoo, Antonina and Ryszard would provide food and other necessities.

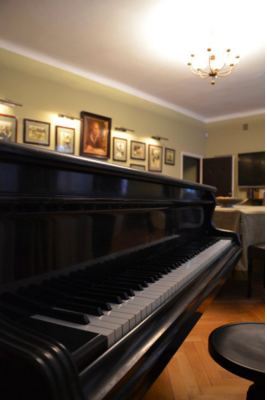

Those hiding inside the house could move around as they pleased. But when danger approached, they were alarmed by Antonina, who would play “Go, go to Crete!” from Offenbach’s La belle Hélène operetta on the grand piano (pictured left in the Żabiński living room).

This would give their guests time to run to hideouts in the attic, a built-in wardrobe, or to leave through a secret tunnel that led from the basement out into the garden. They were also given nicknames – the names of animals – to avoid suspicion from outsiders. The Kenigswein family was nicknamed the squirrels, as a failed attempt to dye their hair blond made them all bright gingers. Another Jewishman taking refuge there, Maurycy Paweł Fraenkel, was called the hamster, as he’d often curl up in a nook with the pet-hamster, reading books.

The secret tunnel to the garden (C) POLIN Museum, Klara Jackl

Some of the Żabińskis guests were strangers who had sought out their help, and others were long-time friends. Magdalena Gross, for example, (pictured below) had been a good friend of the Żabińskis for many years. She was a sculptor who had been in a creative crisis until she visited the zoo and went from sculpting humans to sculpting animals.

Magdalena found shelter in the villa before being taken to the Warsaw ghettos. Antonina called her “the Starling,” and wrote in her memoires that Magdalena always remained graceful and strong; “She would whistle, as starlings do, at her plight.” She was taken to a different hiding place when zoo-employees became aware of her presence in the villa and the risk of being given away became too large.

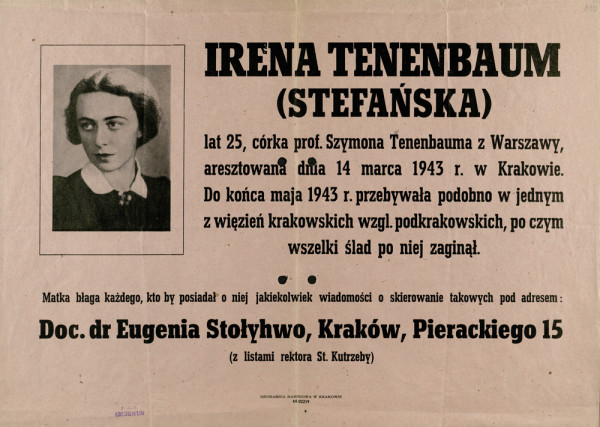

Szymon Tenenbaum and his daughter Irena (c) Museum and Institute of Zoology

Another friend of the family was Szymon Tenenbaum, a passionate entomologist who had traveled the world and even continued to collect bugs while in the Jewish ghetto. He had been in contact with Jan before the war and had left his collection of 300 glass boxes in the Żabińskis’ care. Unfortunately, Szymon’s friends could not convince him to leave the ghetto and go into hiding, even though they made many efforts to get him out. When Szymon passed away in the ghetto in November 1941, the Żabińskis worried about his wife Eleonora and his daughter Irena (pictured above with her father), and they offered them shelter at the villa until they found a safer spot.

Notice of the Tenenbaums’ missing daughter (C) Museum and Institute of Zoology

Unfortunately, Irena had already fled to Krakow, but fell into the hands of the Gestapo. Eleonora was casually led out of the ghetto by the hand of Jan Żabiński and spent several weeks at their villa until she found a hiding place elsewhere. She attempted to find her daughter after the war, but to no avail.

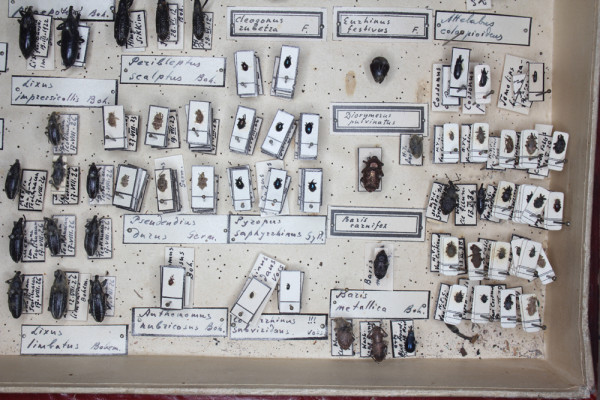

Szymon’s entomological collection survived the occupation and the Warsaw Uprising, hidden away in the Zoological Museum. His collection and writings are currently being analyzed and digitalized. His wife Eleonora wrote in 1945, “I am so happy that the collection was not lost! Each day I witnessed his Sisyphean labor, I helped him count his wee coleopterans. I refused to believe that all that was wasted.”

During the war, Jan Żabiński was active in the underground Armia Krajowa (Home Army) and took part in the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. He was arrested and taken away to a German prison camp. During this time, Antonina continued her husband’s efforts and provided care for the Jews left in the city’s ruins. Fortunately, Jan survived and was able to witness the official reopening of the zoo in 1949 – eventually reaching the ripe old age of 77.

Feeding the Hippo’s in the newly re-opened zoo, 1950 (C) Warsaw Zoological Garden

Jan and Antonio Żabiński have both been honored as “Righteous Amongst the Nations” during a 1968 tree planting ceremony at Israel’s first official Holocaust victims’ memorial, Yad Vashem.

In a report to the Jewish Historical Institue, Jan Żabiński wrote, “I am a Pole and a democrat. My deeds were and still are the effect of a certain frame of mind acquired during my progressive-humanistic upbringing and education at the Kreczmar’s Gymnasium. I tried to analyze the roots of hostility towards Jews many times, and yet I have not found any, aside from those factitiously conceived”.

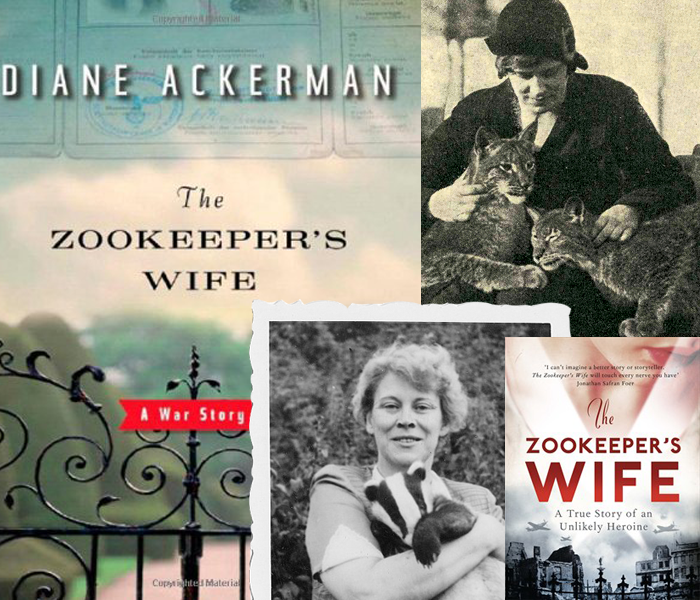

American author Diane Ackerman published a book about the Żabiński family in 2007, titled The Zookeeper’s Wife and inspired by Antonina’s diaries. The book was made into a movie with Jessica Chastain in the role of Antonina and Johan Heldenbergh:

Jessica Chastain and Johan Heldenbergh preparing their roles for The Zookeeper’s Wife

Watch the trailer for the film, which came out in 2017, below:

I think this story, both dreadful for its staging in history and awe-inspiring in its display of true benevolence, is an illustrative reminder that there’s no excuse to turn away those in need when they require it, even when circumstances are dire.

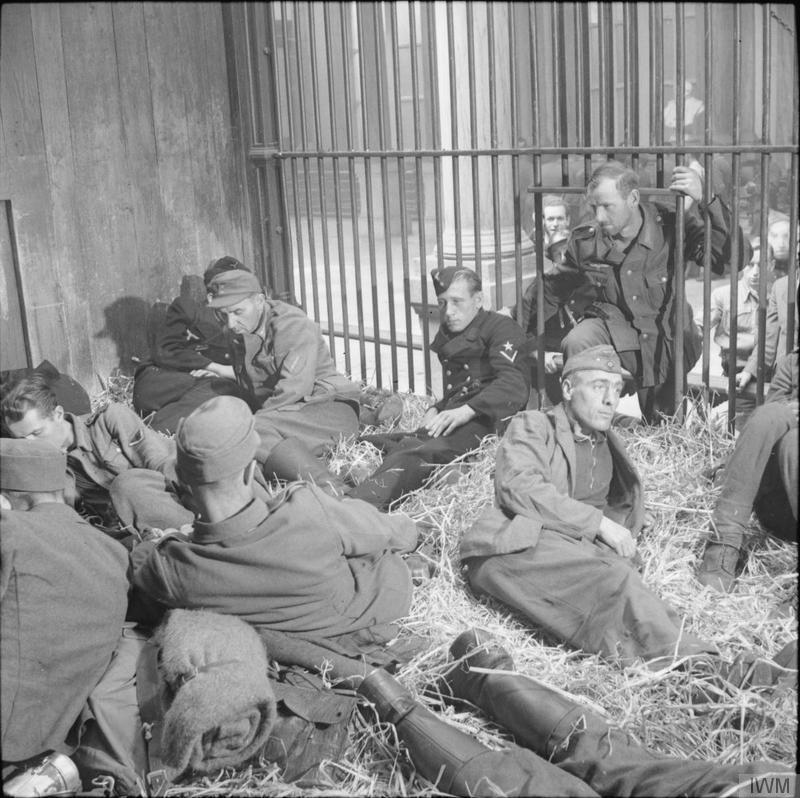

And as a reminder that karma is no nice lady, these are two photographs of German prisoners of war caged in the Antwerp Zoo…

Inge Oosterhoff is a Dutch graduate of North American Studies, currently living in the Netherlands. With a love for the odd and the unexpected she is on a never-ending search for new stories, new people and the very best coffee in the world.

Inge Oosterhoff is a Dutch graduate of North American Studies, currently living in the Netherlands. With a love for the odd and the unexpected she is on a never-ending search for new stories, new people and the very best coffee in the world.