The stony gaze of the statue upon his executor says it all. Most of the bronze “men” that once watched over Parisian streets and public squares of the French Third Republic met a most undignified end many years ago, snatched from their pedestals and erased from the history books. During the Nazi occupation of France in World War II, the co-operating Vichy government ordered the removal and destruction of all metal monuments and statues for the purpose of remelting, unless considered to be of “historical or artistic interest” to the new regime. In other words, sculptures that symbolised democracy, liberal policies, progression, the avant-garde and generally anything that might have offended the Germans, was deemed “ugly” and radical and sent straight to a hellish grave of twisted metal and fallen statues.

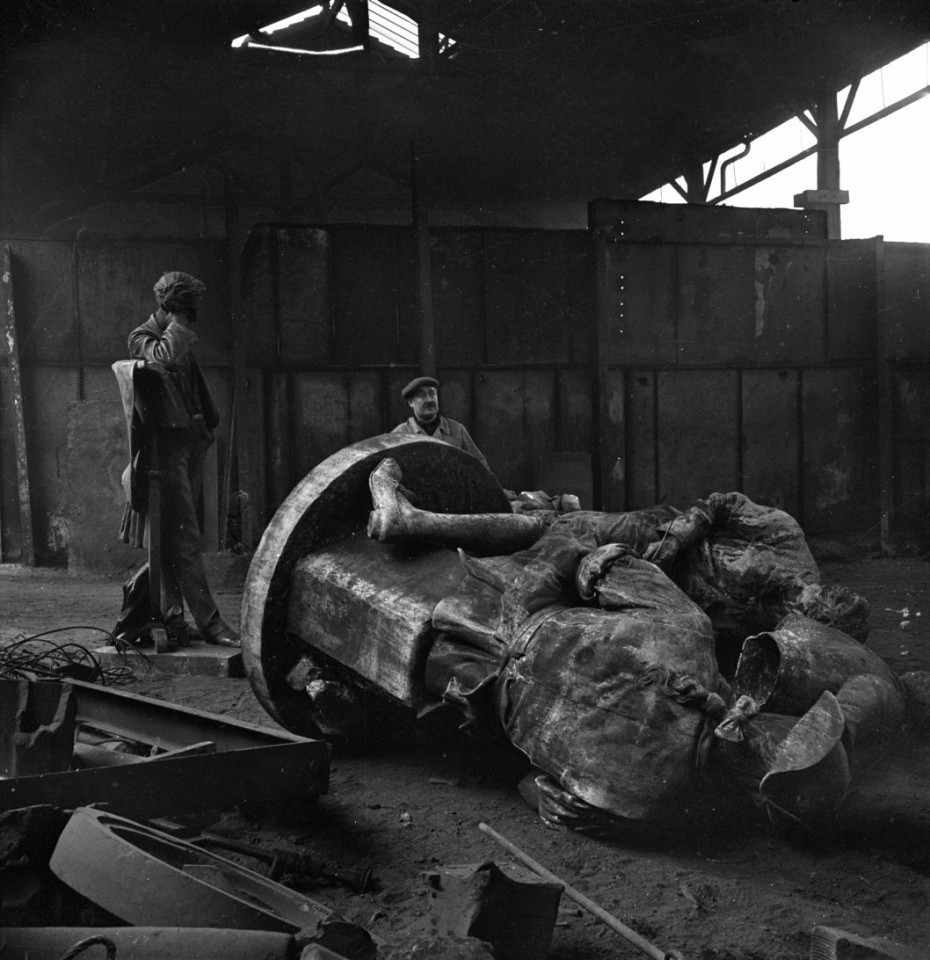

At a scrap metal warehouse previously location at 112 Avenue du Général Michel Bizot in Paris’ 12th arrondissement, the surrealist photographer Pierre Jahan clandestinely captured many of the noble sculptures in their final moments before being melted down. His remarkable photographs were later published in a book La Mort et les Statues (Death and the Statues) combined with John Cocteau’s commentary.

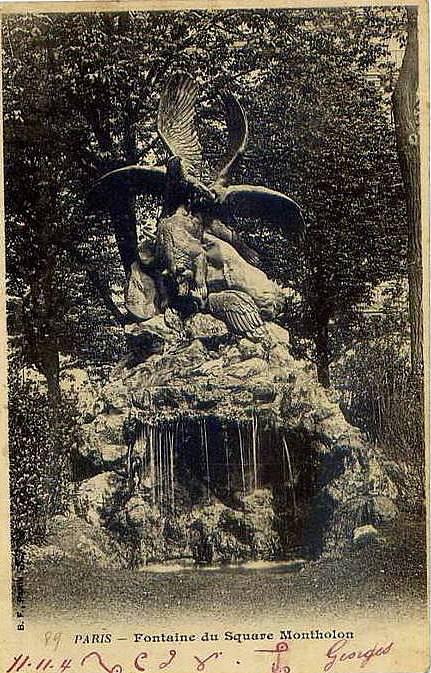

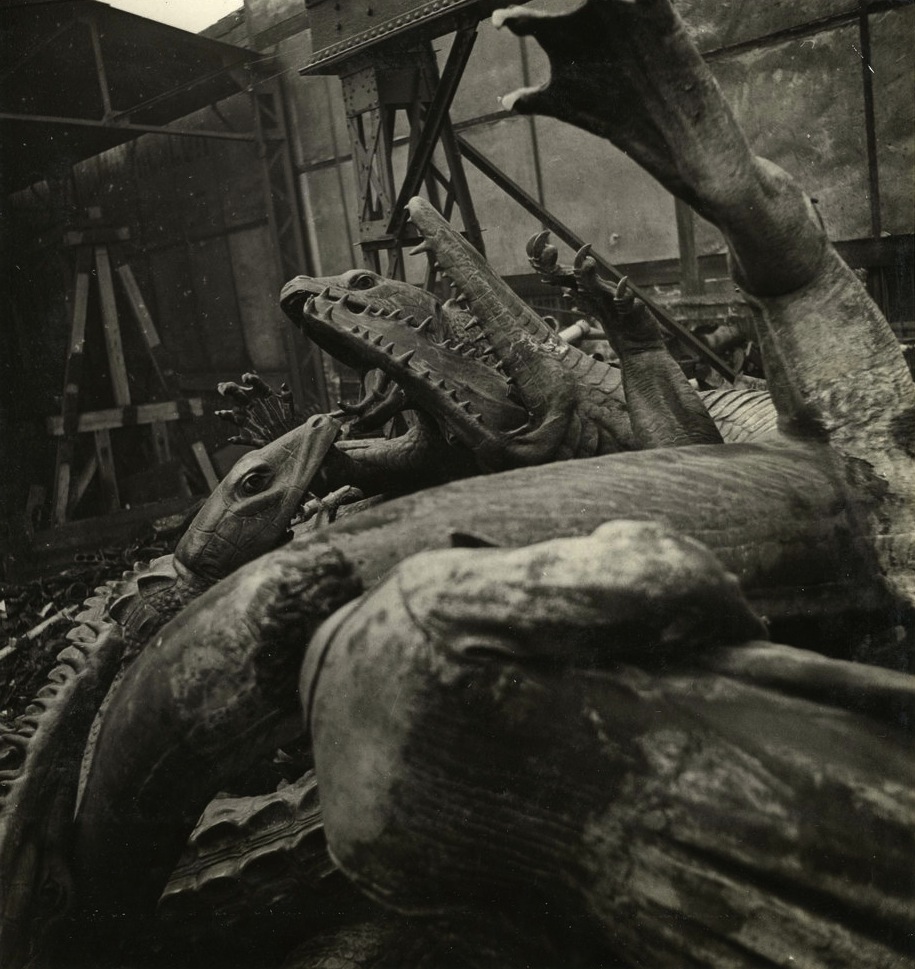

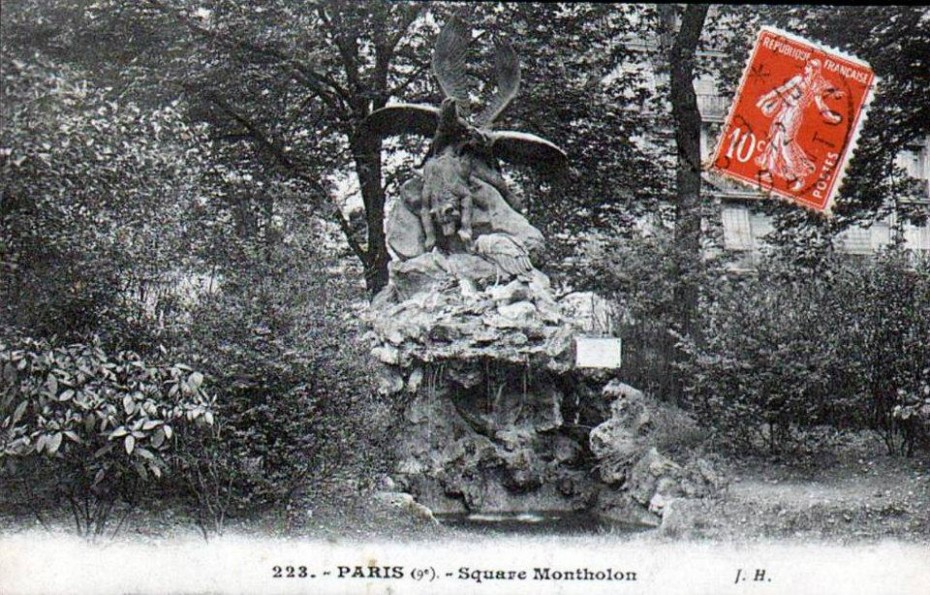

At the scrapyard, the large sculpture awaiting its fate, “The Bear, the Eagle and the Vulture”, which once stood at the fountain of Square Montholon in the 9th arrondissement of Paris, pictured below ↓

The law calling for the destruction of the statues came in October of 1941. The French had signed the armistice with Germany in 1940 following a decision by the cabinet, dissolving the French Third Republic and establishing an authoritarian regime which moved the governmental seat from Paris to the small spa town of Vichy. The agreement allowed the Nazis to keep two million French soldiers in Germany as prisoners, forced labourers and as hostages to ensure the Vichy government would reduce its military forces and pay a heavy tribute in gold, food, and supplies to Germany.

On the other end of the bargain, France would get to keep its Navy and colonial empire under French control, avoiding a full German occupation and maintaining a certain degree of French independence and integrity (even though by 1942, the free zones were also occupied by Germany, ending any semblance of independence).

The new French government reversed many liberal policies, calling for a “National Regeneration”. The independence of women was reversed, conservative Catholicism, anti-Semitism and Anglophobia became prominent, Paris lost its avant-garde status in European art and culture and the media was tightly controlled. While the French government remained in existence, it was very aware that it had to please Germany.

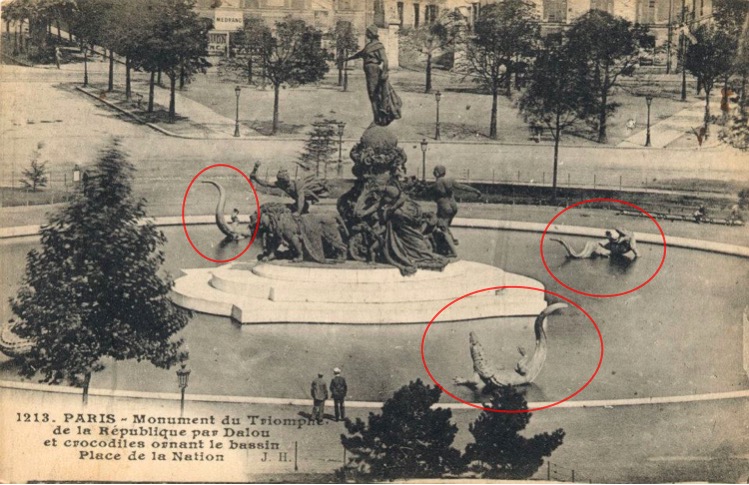

These menacing lizards and alligators had once surrounded the grand fountain at Place de la Nation and symbolised the enemies of democracy.

↓

Thanks to many protests, Jules Dalou’s “Triumph of the Republic” was only temporarily dismantled, but the alligators never found their way back from the scrapyard.

↓

When the Nazis threatened with their plan to recover the bells of all French churches for metal recycling, the Vichy government feared an intensified and problematic resistance to the occupation. So they gave in and offered an alternative. Throughout France during the Second World War, 17,000 statues, both commemorative and decorative, disappeared.

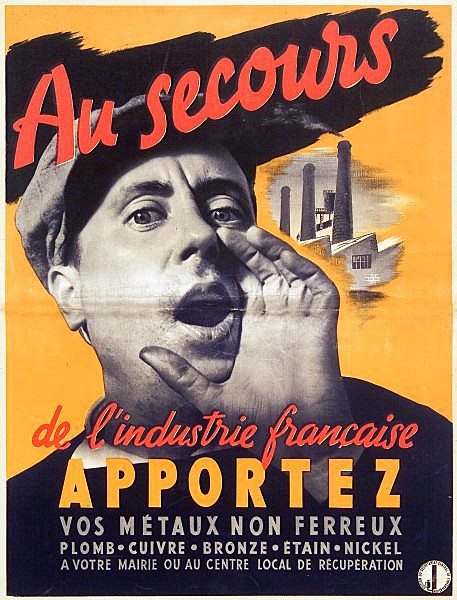

The Vichy government used propaganda to claim the statues were being reduced to their material dimensions for the needs of national agriculture and industry.

In actual fact, much of the non-ferrous metal contributed to German weapons production. Some of it was even used to make copies of famous French works for the Nazis and sent to the Parisian studio of Arno Brecker, the German sculptor best known for his public works in Nazi Germany.

The fallen monument to Claude Chappe, French engineer and inventor of the first practical telecommunications system of the industrial age, telegraphy, making him the first telecom mogul with his “mechanical internet”. Sculpted by Emile Louis Macé.

↓

Claude Chappe’s statue as it was at the junction of Rue du Bac, Boulevard Raspail and Saint Germain in the 7th arrondissement.

A crushed statue of the Marquis de Condorcet, French philosopher, mathematician, and early political scientist who unlike many of his contemporaries, advocated a liberal economy, free and equal public instruction, equal rights for women and people of all races. His ideas and writings were said to embody the ideals of the Age of Enlightenment and rationalism, and remain influential to this day.

↓

The Marquis de Condorcet’s statue as it was at the centre of a prominent public place on the Quai Malaquais along the Seine.

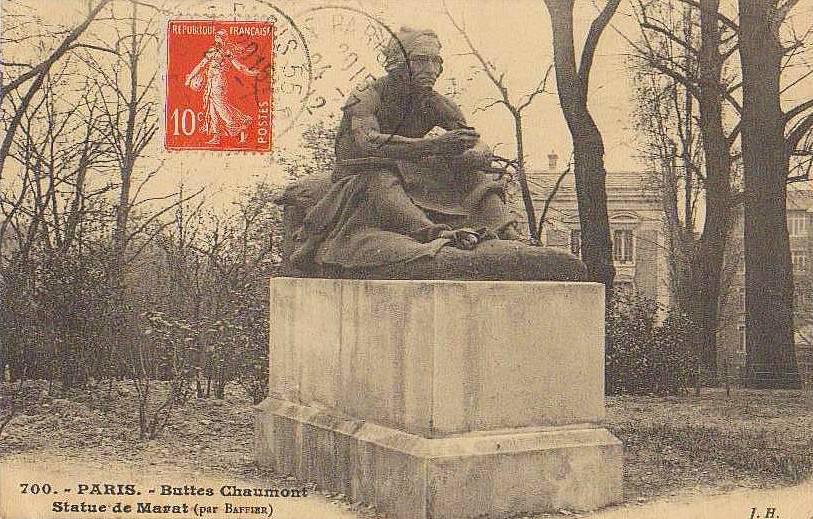

The decapitated statue head of Jean-Paul Marat, a physician, political theorist and scientist best known for his career in France as a radical journalist and politician during the French Revolution and his advocacy of basic human rights for the poorest members of society.

↓

Jean Paul Marat’s full statue as it once stood in Paris’ popular Parc des Buttes Chaumont.

A close-up of the fountain statue of “The Bear, the Eagle and the Vulture”

↓

Pictured as it was in the Square Montholon.

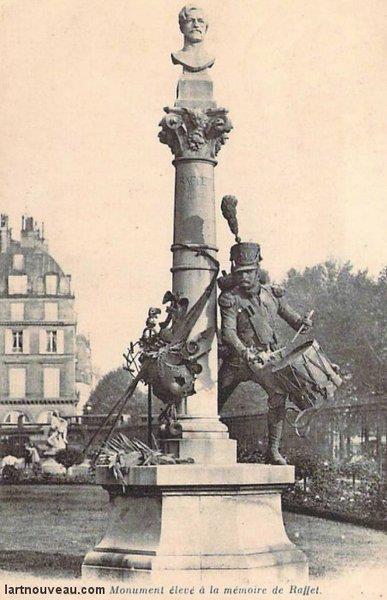

The leg and drum of the statue of Auguste Raffet, a French illustrator and retrospective painter of the Empire.

↓

The statue as it was in the gardens of the Palais du Louvre. The stone pedestal also disappeared.

Only the statues of “indisputable national glories” were spared, such as those of Joan of Arc, Henry IV, Louis XIV and Napoleon Bonaparte. Statues of Saints and Queens and Kings were also left alone.

Voltaire, Rousseau, Condorcet, Marat, Camille Desmoulins, Gambetta, Victor Hugo, Etienne Dolet, the Chevalier de la Barre, Ledru-Rollin, and Emile Zola all went to the foundry.

It’s often assumed that Paris made a lucky escape during the invasions and cultural purges of World War II for the most part, but Pierre Jahan’s haunting photographs reveal a somewhat forgotten loss for the city during one of the darkest chapters in French history. As much as one tries to remind themselves that the statues are only lifeless, metallic structures, the images are a distressing portrait of violence and vandalism and remain tragic symbols for the real victims of war.

La Mort et les Statues (Death and the Statues), Pierre Jahan photos via here.