At lunchtime, the women had to be separated in the cafeteria because everything they touched turned yellow. They were called the “Canary Girls” because of their bright yellow skin and green or ginger-coloured hair. With the nation’s men at war and male labour in short supply, Britain’s women had been recruited to ramp up production ammunition and were paid on average less than half of what the men were paid. By the end of the war, roughly 80% of the weaponry used by the British army was being made by women who were in fact paying very dearly to “do their bit”.

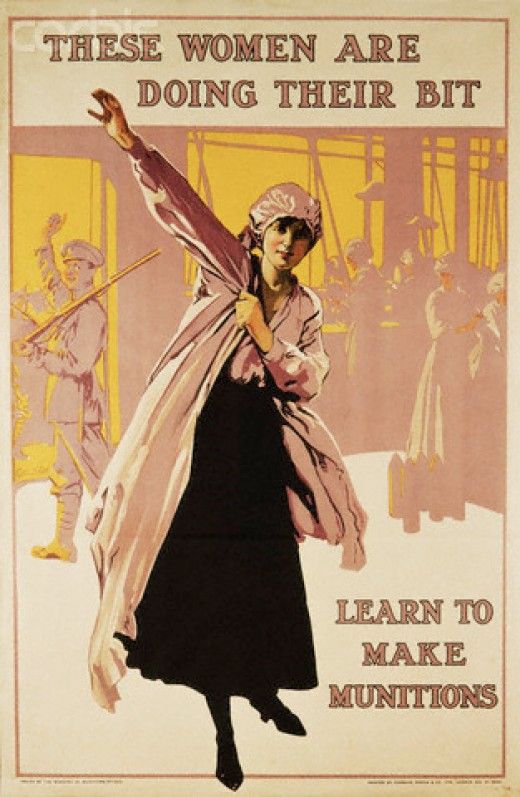

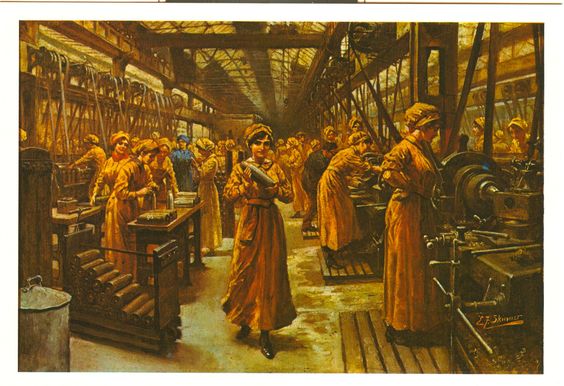

They had gone from working as housemaids, cooks and nannies to being employed in munitions factories where became known as munitionettes. They performed both heavy-duty and delicate tasks that require more skill than brute force; handling detonators and explosives, machining shell cases etc.

But the women also worked with hazardous chemicals on a daily basis without adequate protection, such as trinitrotoluene (TNT). Prolonged exposure to the sulfuric acid caused depigmentation, turning their skin yellow. It was believed that the canary with blue eyes were particularly adept calibration work.

Other strange symptoms included hair turning green or falling out altogether, chest pain, breast deformation, weakening of the immune system, vomiting, anemia, migraines and fertility problems. Cases were even reported of munitionettes giving birth to yellow children. One “baby canary” whose mother worked in a munitions factory in Banbury, remembered that in her town, most children were simply born that way. Doctors said that only time would fade the discolouration.

Image via “Nice Girls and Rude Girls: Women Workers in World War I” by Deborah Thom.

Pictured above is an advertisement for Oatine Face Cream, a product which was marketed specifically to Canary Girls. Notice the 155-mm shells scattered about on the ground.

TNT poisoning became such a common problem that it was frequently mentioned in early 20th century medical journals. They stated that only 24% of the workers (male and female) showed no symptons of TNT poisoning (based on blood tests).

A short story based on the lives of munitions workers in WWI by Jess Milton

The body’s reaction to to the TNT usually began with sneezing fits, a bad cough, severe sore throat and profound digestive woes. Some women said the worst of it was the constant metallic taste in their mouth. While some simply couldn’t tolerate it, most munitionettes only left after their health failed.

But turning yellow, falling ill from the poisons lurking in the air and unfair pay weren’t the only concerns for these women. The risk of exploitation was actually much less than the explosion. Blasts occurred relatively frequently and were another ever-present hazard. The explosives the munitionettes were working with ignited on several occasions, injuring or killing the workers.

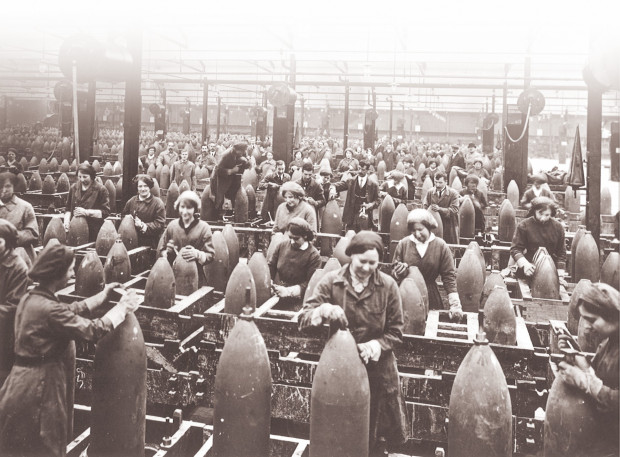

The deadliest blast occured in 1918 when an explosion at the National Shell Filling Factory, Chilwell killed over 130 workers– the biggest loss of life during a single explosion during the First World War and Britain’s worst ever disaster involving an explosion to date. Amazingly it was a tragedy that was kept secret at the time.

Munition workers at the National Shell Filling Factory, Chilwell

On average, two munitionettes died a week, but the government took great care to hide these realities, for one reason or another. There were German spies in London keen to use such information to their advantage. With color photography still a novel invention and the nature of the story, I had a hard time finding any ghoulish images of yellow-tinted women you’re probably curious to see.

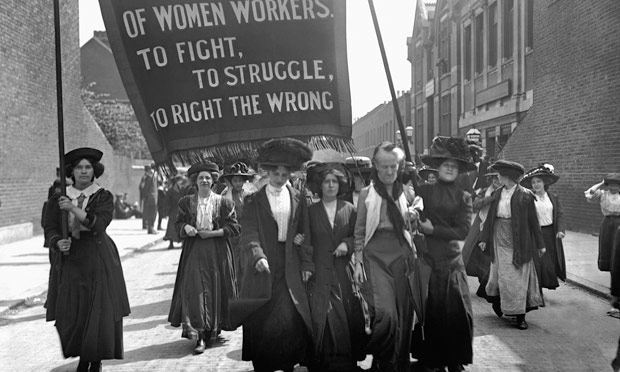

On another note, it’s perhaps just a coincidence then that this all happened the very same year that women (over the age of 30) were finally given the right to vote for the first time in Britain.