I wasn’t exactly expecting the world when I was emailed by a local record collector urging me to visit an endangered private music museum in Paris at the foot of Montmartre. The Phono Museum? Never heard of it. Within my network of vinyl fanatic friends and small museum hunters, surely we would have come across such a place before if it was any good. Oh, how wrong one can be…

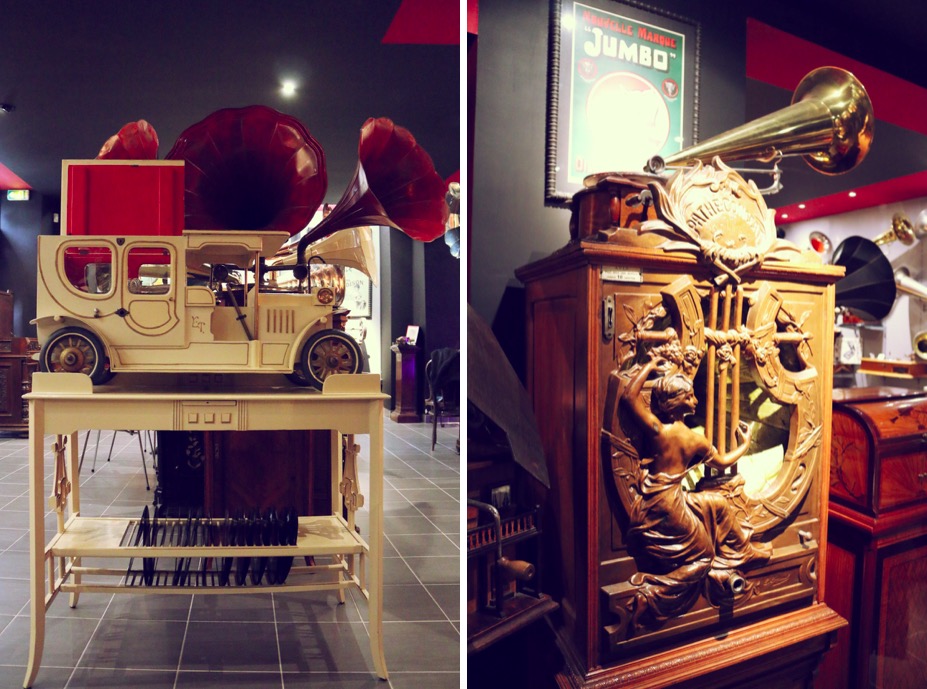

Hidden in plain sight in the shadow of the Moulin Rouge is without a doubt one of the most fascinating treasure troves this city has to offer. The Phono Museum is what I imagine a music lover’s dream looks like. And when I stepped inside, my jaw hit the floor. So many questions. Who collected all this stuff? Shouldn’t those antique gramophones be behind glass? How can this place be in danger of closing down? And wait just a damn minute, is that a Swiss chalet dollhouse doubling as a record player?

You can still play music on that?

That’s the thing about the Phono Museum. Every last machine in this place works as well as the day it was sold.

From the art nouveau Pathé juke box, an old Parisian restaurant’s motor car gramophone (the vinyl goes in the back seat), to the kid’s wind-up record players– everything still plays music.

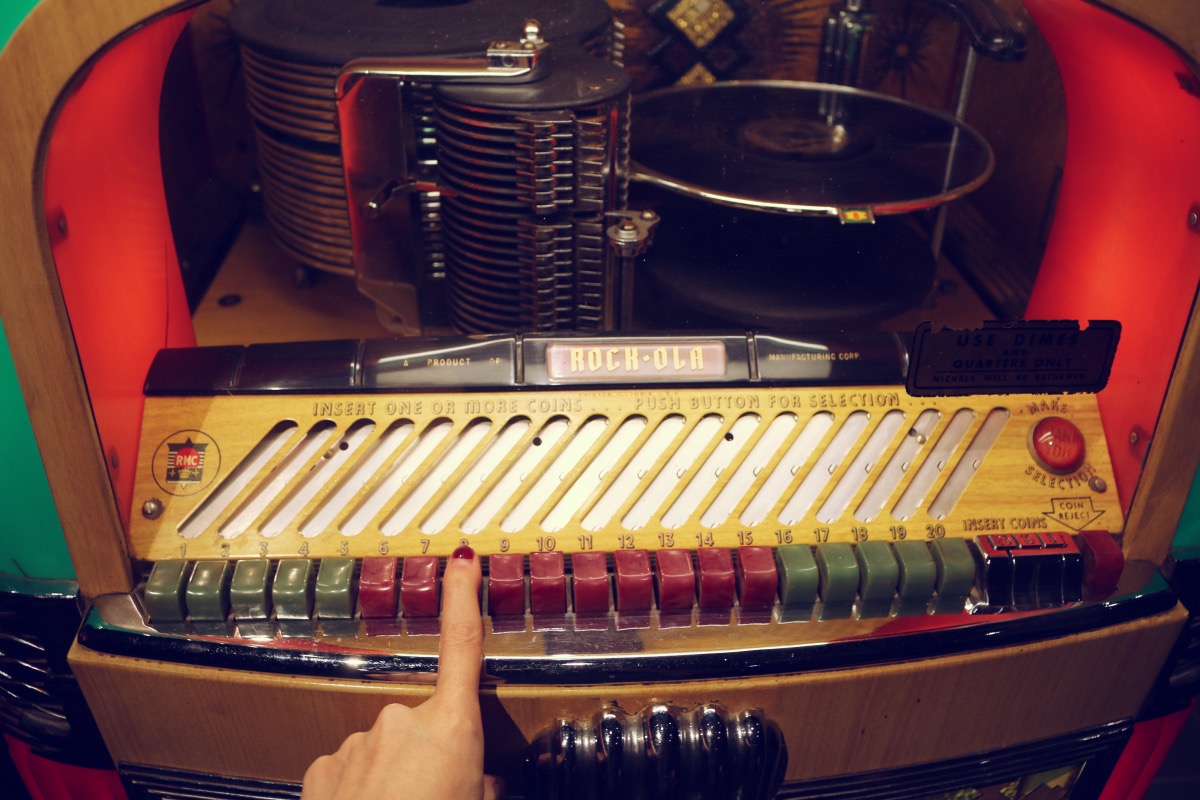

Just pick any phonograph in the museum’s endless collection and have a listen to the sound of a bygone era. Most of the machines actually have the very same music and vinyls they were found with, like this jukebox bought at auction along with the previous owner’s old favourite tunes still in the playlist.

You want to have a look inside the juke box? No problem! Have a poke around its belly…

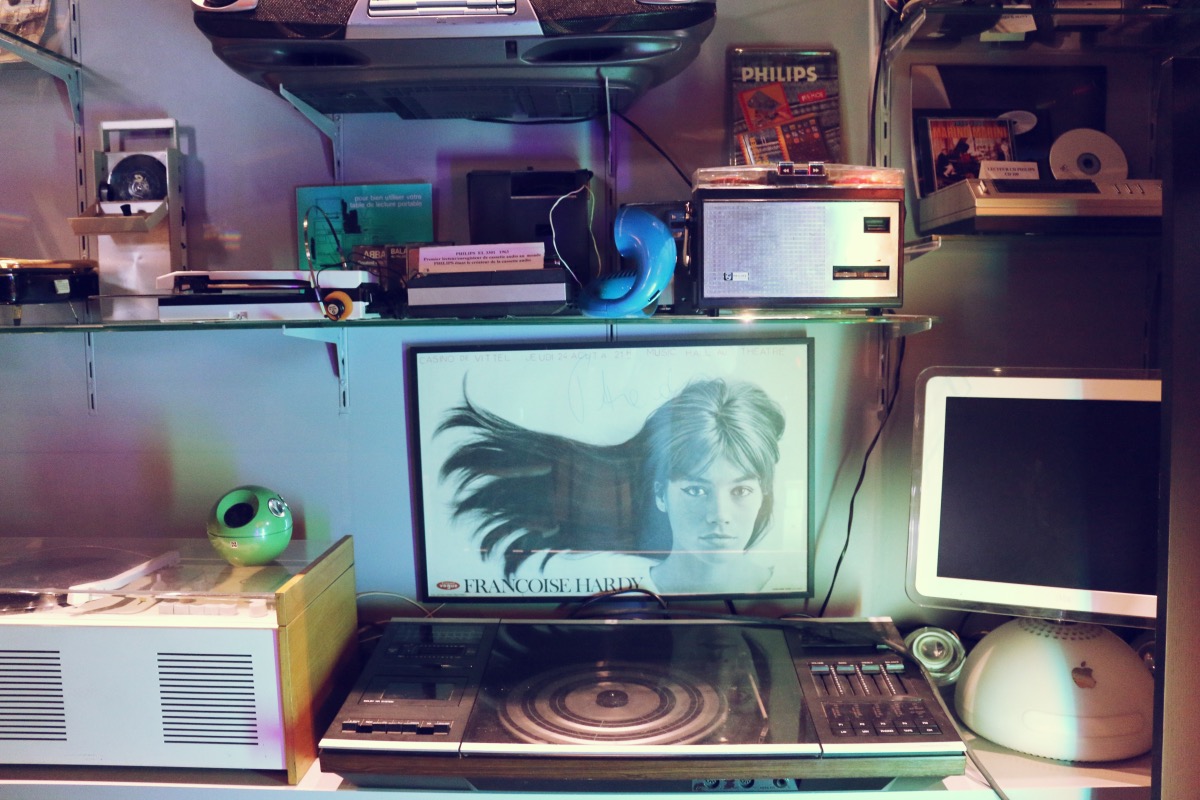

There’s 140 years of recorded sound history stuffed inside this Aladdin’s cave and no outmoded format has been forgotten from the timeline. I think my favourite model might have been this bistro table moonlighting as a gramophone ↓

“The sound would have been at the same level as the diners, to be enjoyed as intended, not the way they blast music out of ceiling speakers in restaurants these days,” explains Jalal Aro. That’s the owner, the guy who collected it all, who knows the story and inner-workings of every last musical gadget in this place…

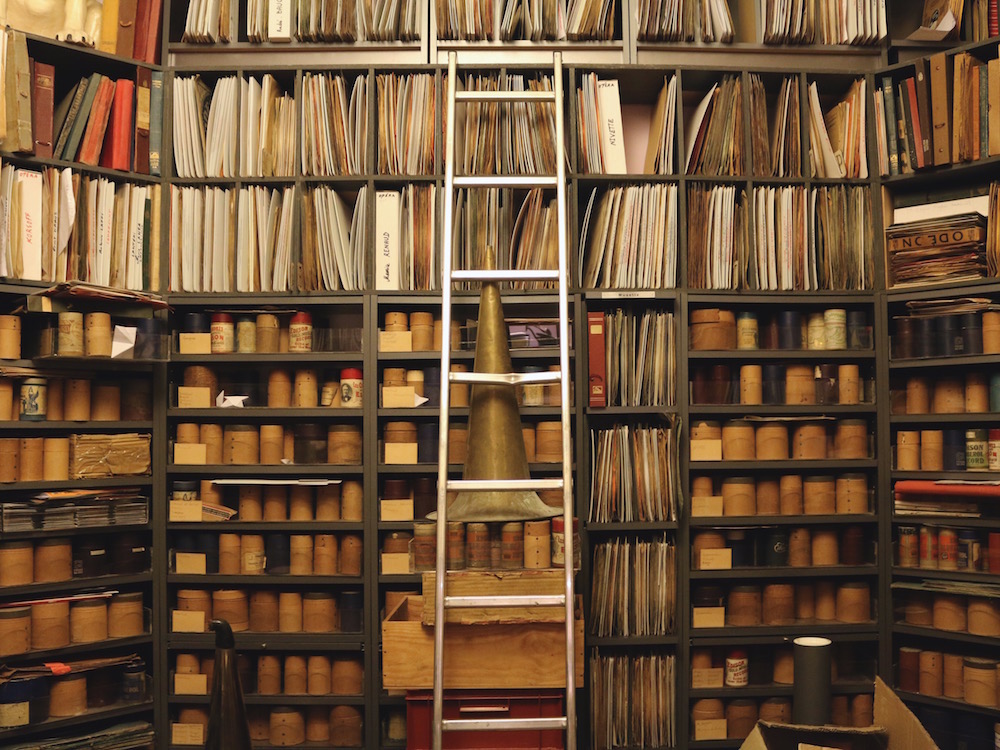

How did one person accumulate all this stuff? “Oh there’s much more that’s not even on display.” Jalal developed a knack for convincing landlords to lend him extra storage space over the years to hold his ever-growing collection.

He’s the guy that Woody Allen and Quentin Tarantino come to when they need vintage music props. You can spot some of the Phono Museum’s pieces in Midnight in Paris or Inglorious Bastards. He’s a passionate collector and self-taught specialist in talking machines and old records, and he wants to share it all.

Jalal has so many back-stories, not just about the things you see in his museum, but about the neighbourhood that nurtured African American musicians between world wars and legitimised jazz for the rest of the world. “You see that hotel?” he points to the building with the art deco detailing just across the street. “Josephine Baker and Maurice Chevalier performed at the opening.” These are the kind of historical anecdotes that can be easily forgotten if not repeated by people like Jalal. It’s how a once revered building becomes just another cheap hotel on the boulevard; how a neighbourhood loses its soul if you look the other way for too long.

With an infectious laugh, his old-school cool cat style– the leather jacket, flat cap, and the best sideburns I’ve seen since Starsky & Hutch– Jalal is one of those memorable characters that make up what I like to call the “Humans of Montmartre”. And I believe it’s the appreciation of these nostalgic characters and the survival of their eccentric establishments that will keep the true spirit of Montmartre and bygone Paris alive.

At the back of the Phono Museum is the record store Jalal opened in 2004, the Phonogalerie, filled with rare recordings, antique gramophones and and original artwork for sale.

Did I not mention the art?

Not a single one of these centrepieces is a reproduction. Jalal only buys music memorabilia if it’s “one of five original edition posters” or “one of only ten paintings known to exist today”. Many of them have been professionally restored, which requires a technique that actually involves washing the paper.

Jalal’s collection of phonograph cyclinders (the earliest commercial medium for recording and reproducing sound) is nothing to sniff at. In fact I wonder if he ever actually counted them all whether he might find he has one of the largest collections going.

There are so many, he’ll occasionally break one deliberately just to show young visitors who have never come across them before, just how fragile they are…

One of the rewards for donors helping the museum to stay open, Jalal tells me, will be to make a record on a phonograph cylinder at the museum, as in the earliest years of recorded sound, and take it home.

I was having such a good time that I’d almost forgotten about that, or just didn’t want to bring it up. This place might be closing down.

The private museum cannot survive on admission fees alone. After a heavy investment in the preparation of the museum prior to opening in order to be up to code, the association now finds itself in debt to its landlords. Request for funding from the City of Paris to assist in the operation of the museum has unfortunately been met with no response up to now. And at this point Jalal is at risk of losing the lease, which would mean the immediate closure of the museum.

If the Phono Museum succeeds in crowdfunding and saving itself from inevitable closure, it has big plans, including building an in-house recording booth, a space dedicated to researching public music archives, organising vintage dance classes, temporary exhibitions, musical festivals and more. But not before they pay off the debt, hire a full-time employee and finance the installation of exterior signage for it to be less “hidden in plain sight” and get more butts inside the museum.

If you want to help, awesome! Just think of it as your museum entry fee, which comes complimentary with any donation of just €10 or more. Other rewards include access to the museum out of hours, an original etched label French Pathé record, an invitation to a local tour of recorded music history in Paris or a training workshop on the operation of phonographic records and cylinders. Find out how/ what’s involved when you make a donation here.

The bright young Parisian record collector, Thomas Henry, who urged me to visit in the first place, is responsible for getting Jalal and the Phono Museum set up on the easy-to-use crowdfunding platform, Ulele. Of course all this history is priceless, but it won’t be worth anything if the future generation doesn’t take an interest in preserving. So I’d like to thank Thomas for opening my eyes to such a place.

Instead of borrowing props from here, they should be making movies about it.

Stay tuned on their FB page and in the meantime, tell your friends, send word to music lovers across the world. Save the Phono Museum!!

UPDATE

It is my absolute pleasure to confirm the Phono Museum’s crowdfunding project has been a success! You can still contribute until midnight tonight to give them a little extra boost in making sure the museum stays open. And if you’re in Paris tonight, there’s a museum open night to celebrate until the clock strikes twelve. 10 Rue Lallier, 75009 Paris.

Hungry for more Paris? The updated edition of Don’t Be a Tourist in Paris is now available. Or become a MessyNessy Keyholder to gain access to our Travel eBook library and a direct line to our Keyholder Travel Concierge to plan your perfect trip. Need help planning a weekend in France? Need some restaurant recommendations for a remote village in the North Pole? We’re here to help.