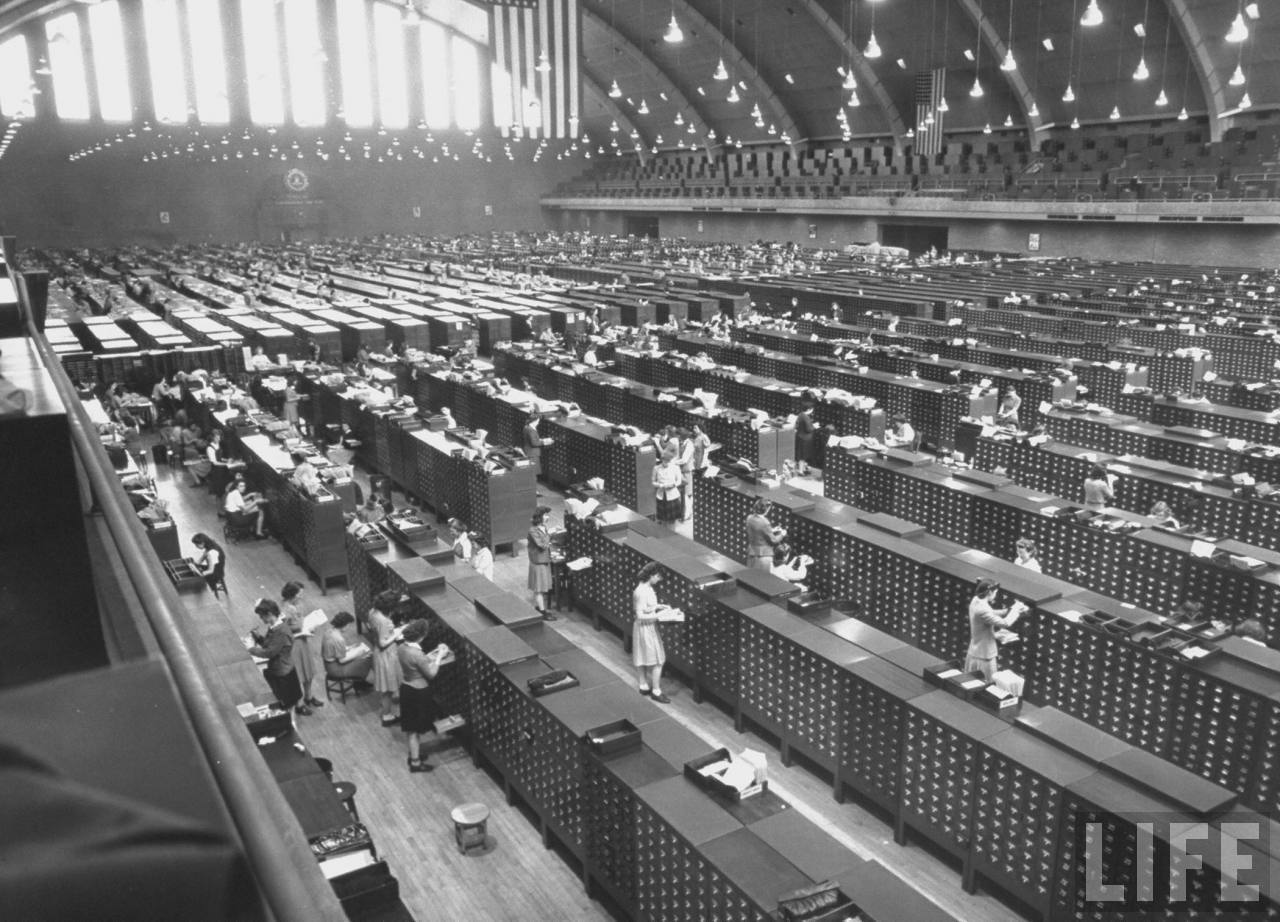

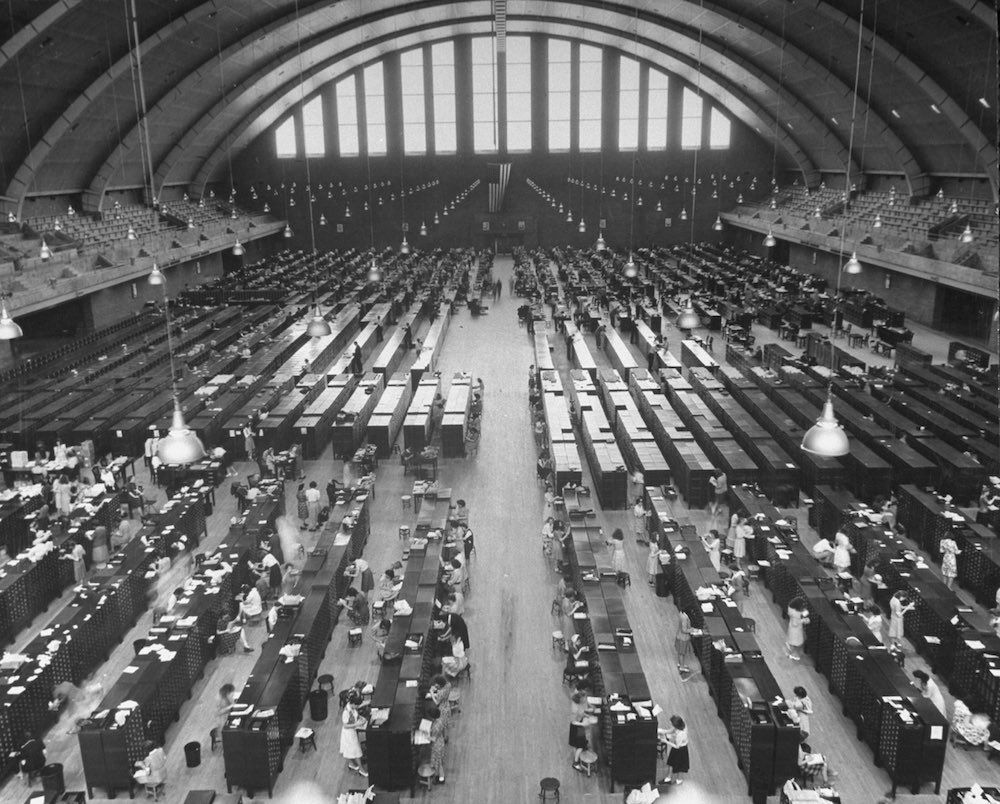

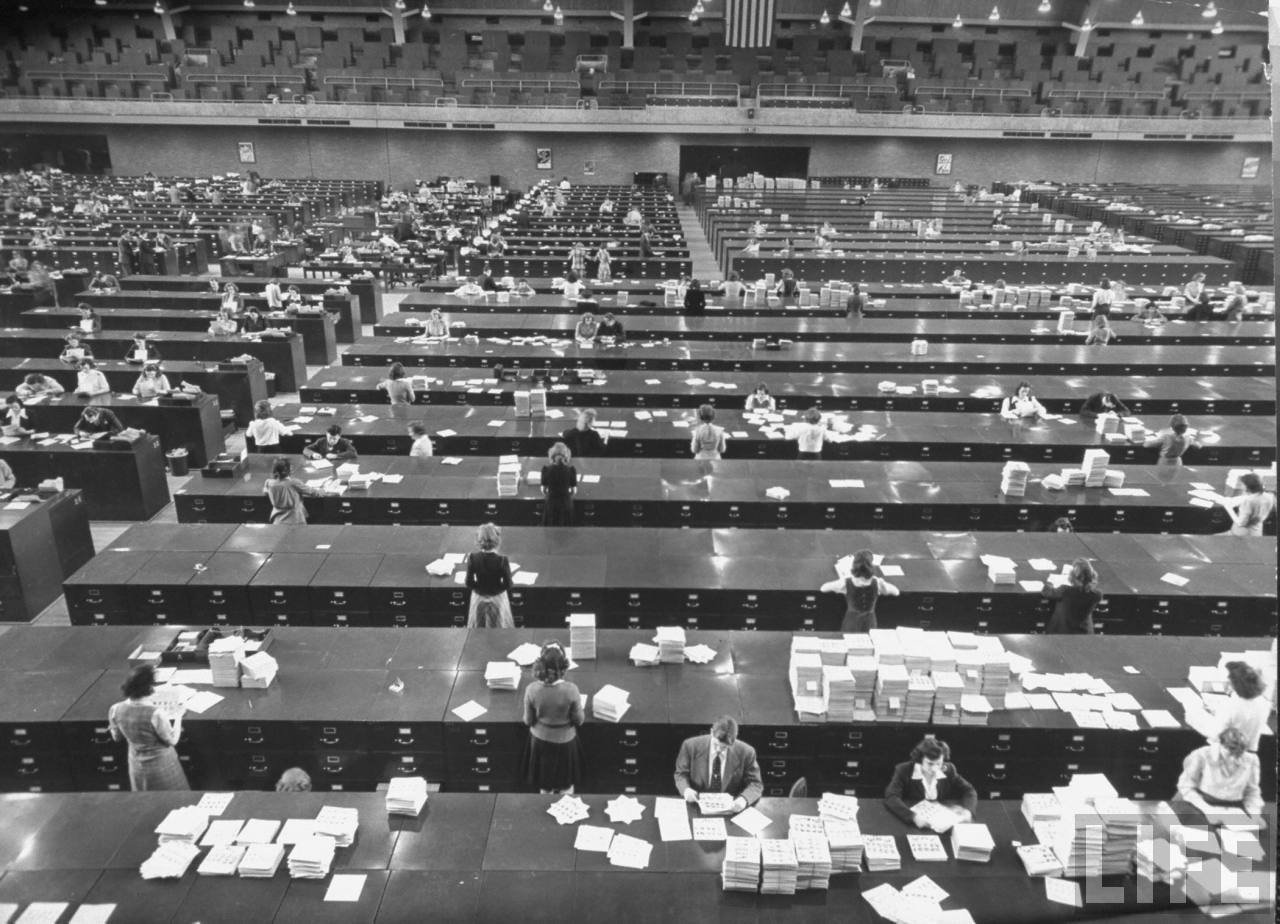

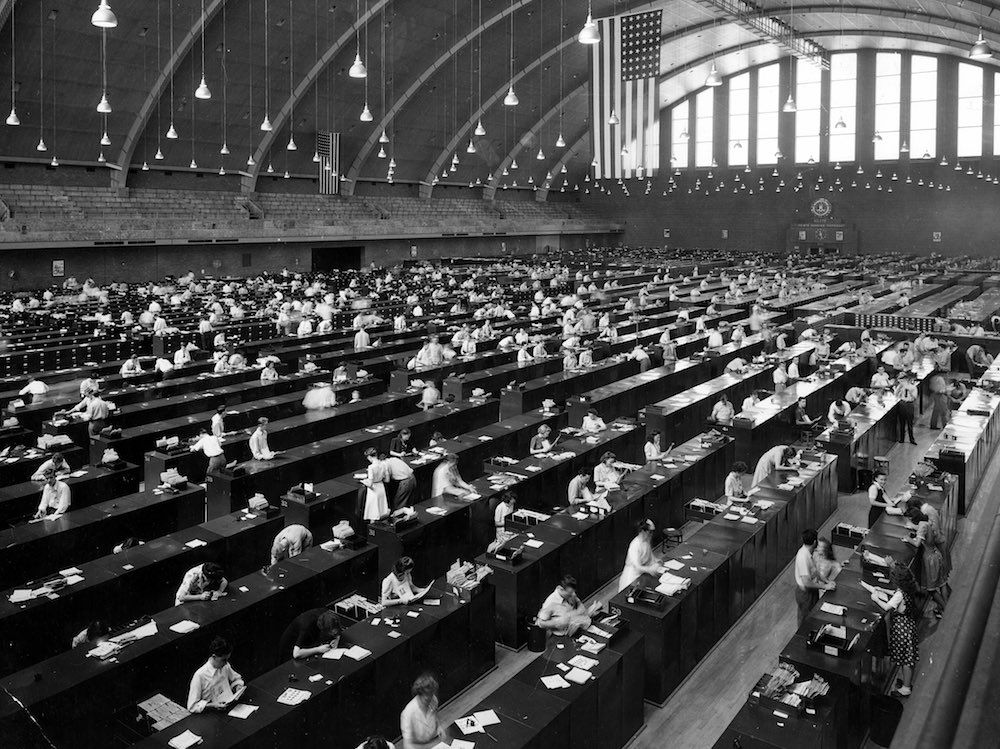

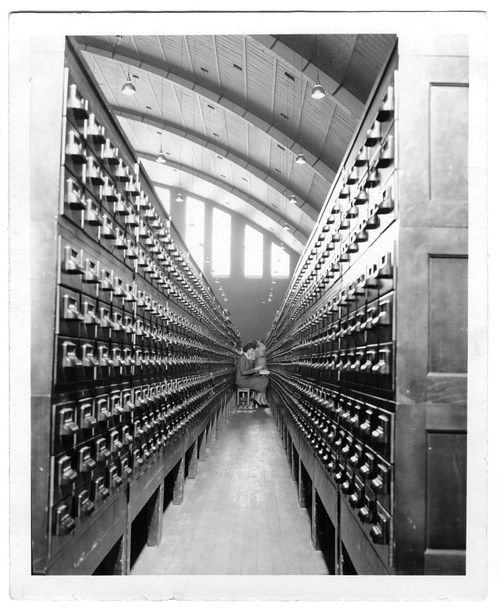

Before the FBI went digital, it looked a little more like a giant stock warehouse for Amazon.com. In the 1920s, the bureau was only employing 25 workers to classify around 800,000 print cards, but by 1943, there were more than 20,000 employees sorting through 70 million fingerprints. At the height of wartime, the archives were so overwhelmed that the FBI eventually moved into an 8,000 square foot facility in the National Guard Armory in Washington D.C. They called it the Fingerprint Factory.

Photos by George Skadding for Life magazine (c) Getty Images

With the war came new responsibilities for the FBI. No longer was it only investigating domestic crimes committed in the United States, the bureau was now tracking suspected spies, gathering information abroad, pursuing draft dodgers, tracking immigrants and even their own personnel who could be potential saboteurs. There were fingerprint cards for members of the armed forces, US foreign agents, war-material manufacturers and even all the government girls who were working amongst the labyrinthine archive of cards themselves. Everyone needed background checks. Agents looked into nearly 20,000 reports of sabotage during the war, of which they found 2,282 actual attempts.

Crime was increasing on the home front too as wartime made an ideal opportunity for defrauding the government and stealing from its vast military supplies.

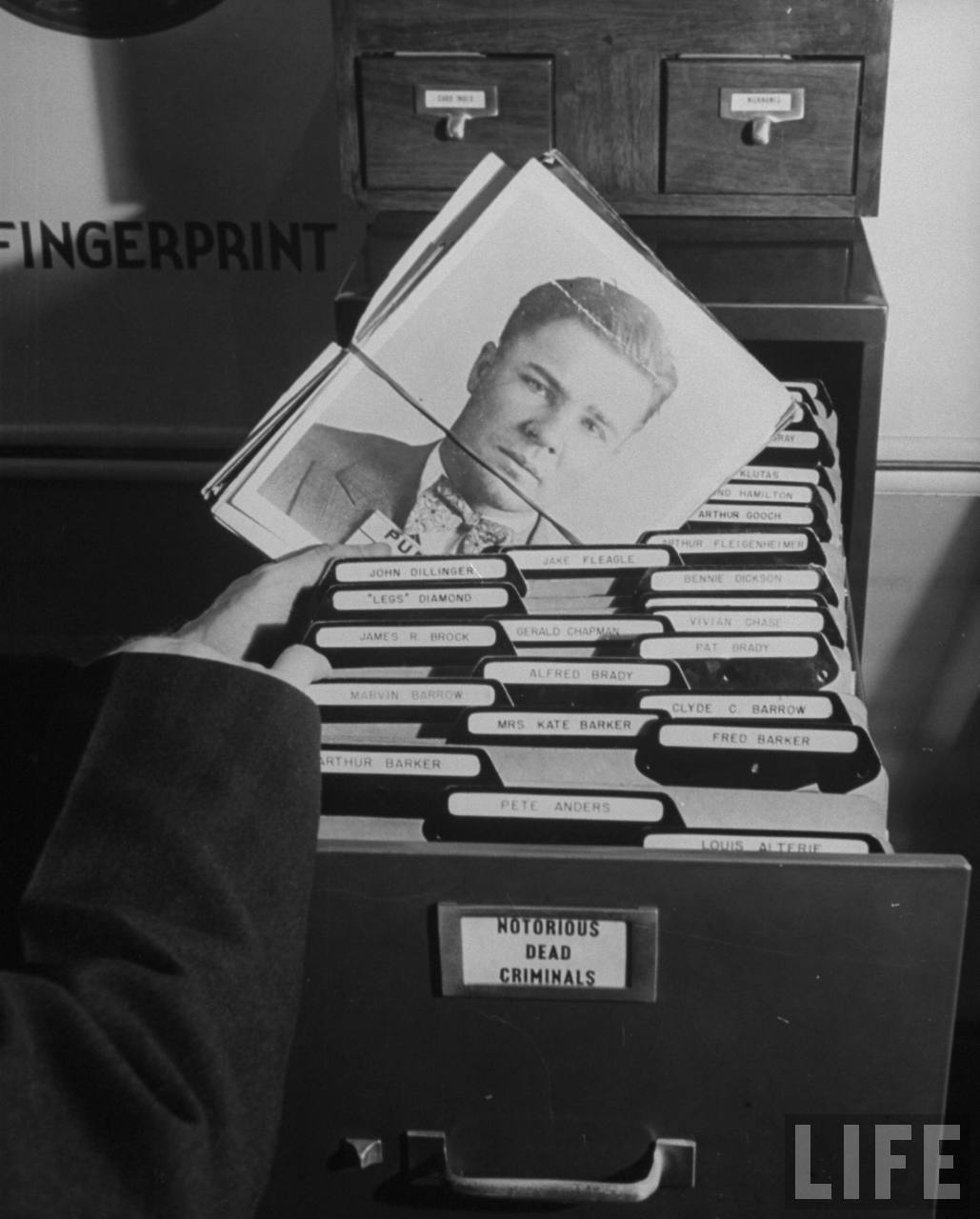

Yes, the FBI had an actual file called “Notorious Dead Criminals”.

Photos by George Skadding for Life magazine (c) Getty Images

Photos by George Skadding for Life magazine (c) Getty Images

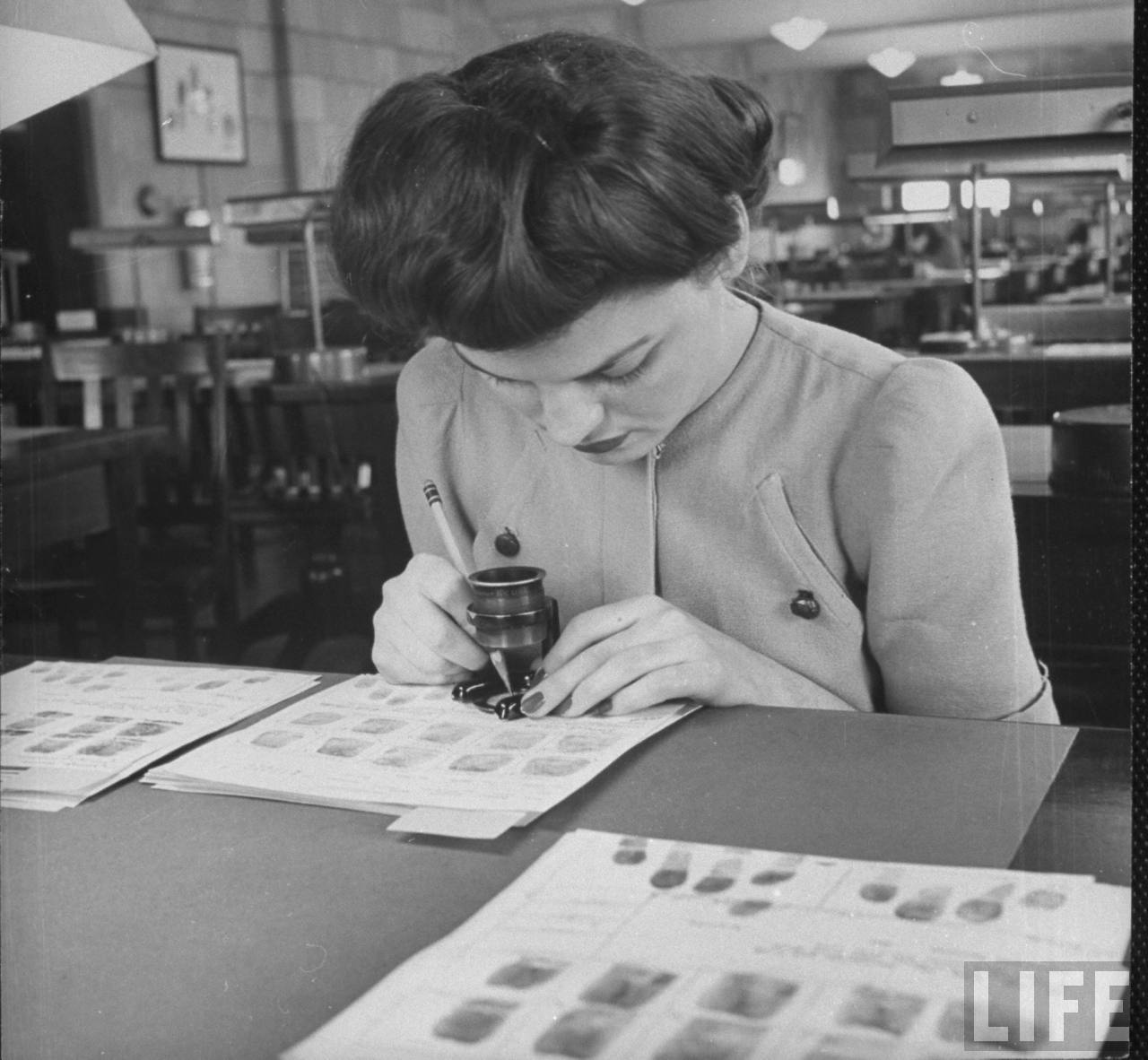

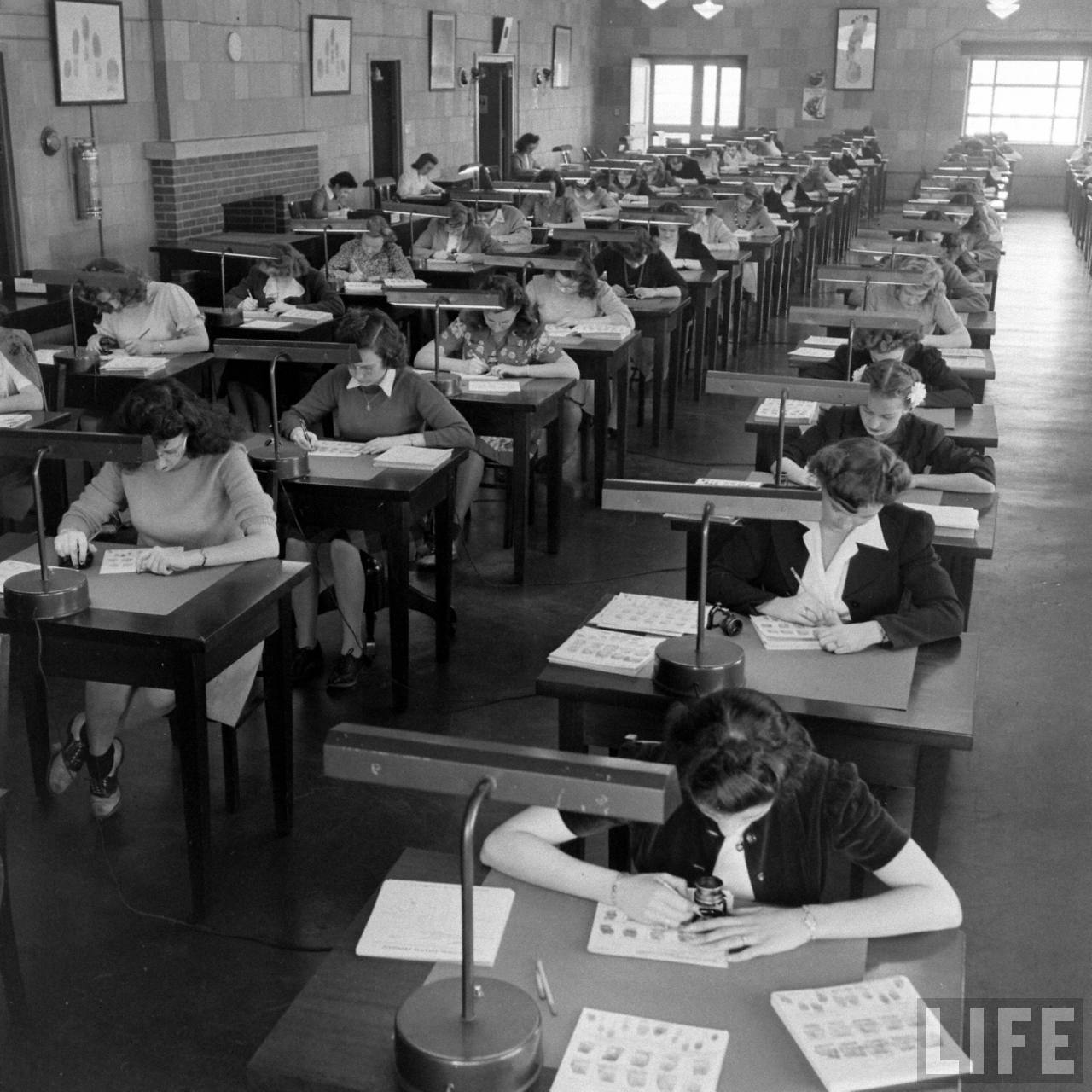

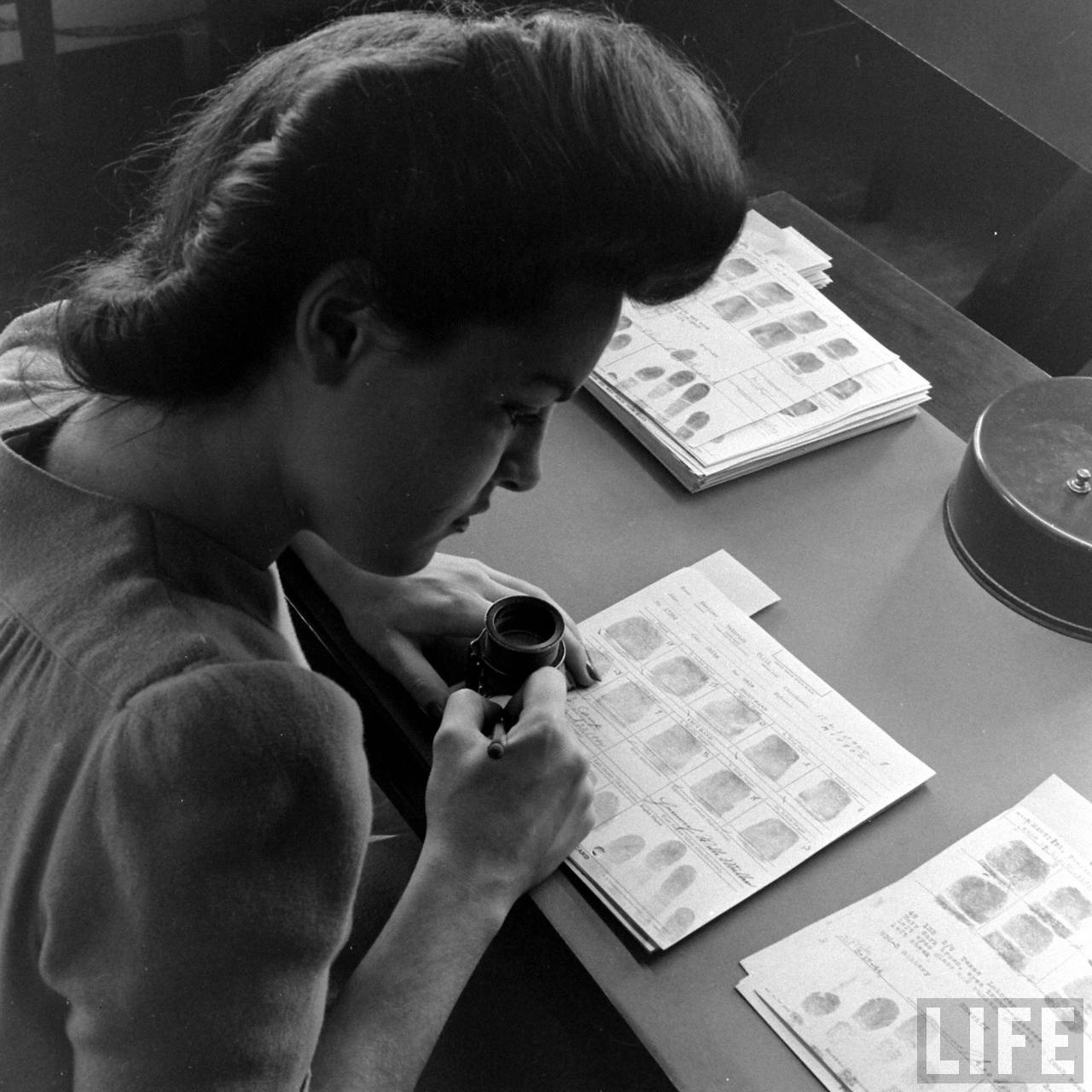

The thousands of women working at the FBI in the early 1940s were trained in the Henry System of fingerprint identification, a method used in the United States and other English-speaking countries which manually categorised fingerprints by their physiological characteristics.

A complex and time-consuming process, essentially, these ladies would spend their entire day assigning numerical value according to the ridge patterns of loops, whorls, and arches they saw in the magnified fingerprints.

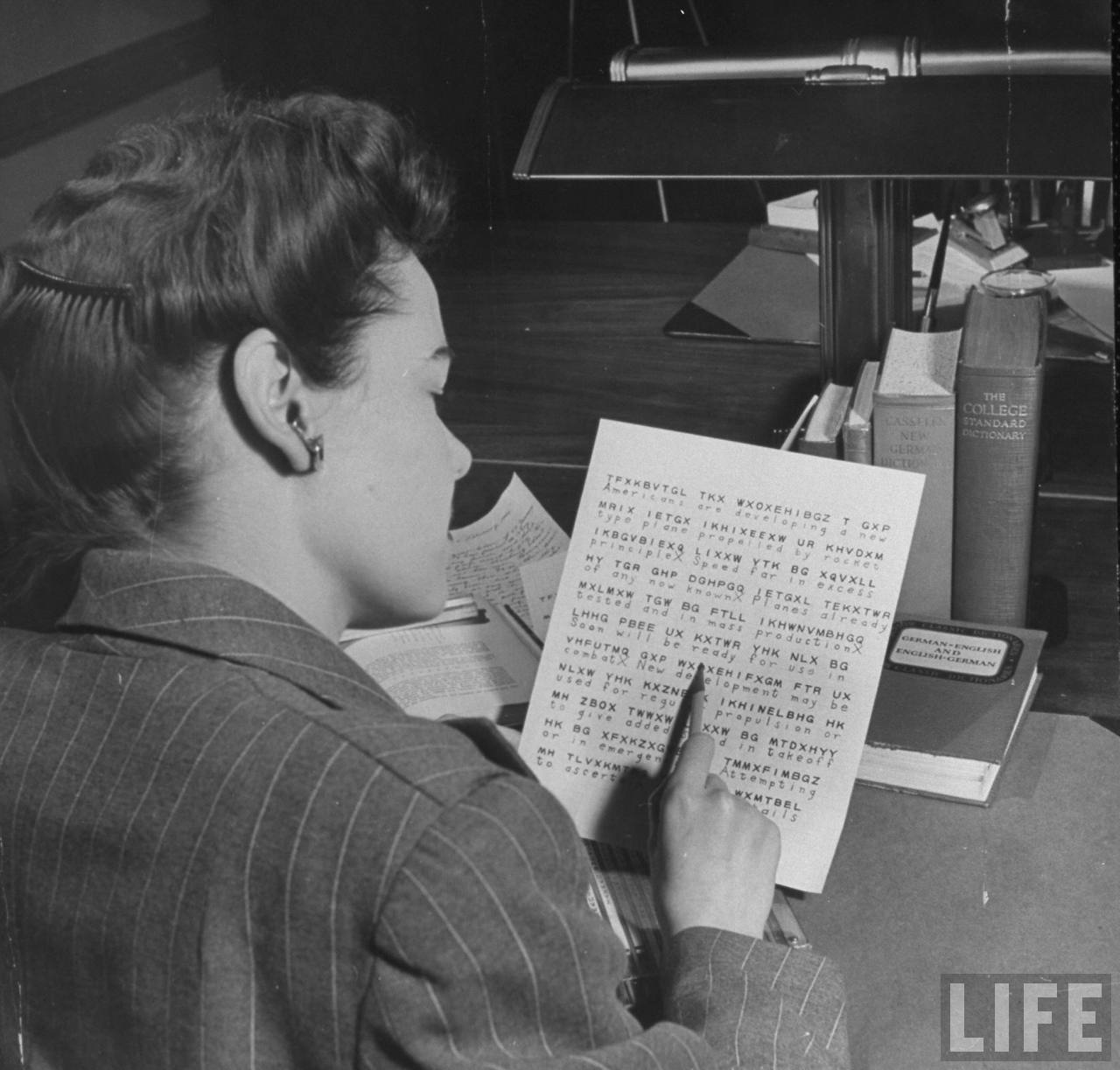

It was as this time that the bureau began investigation cases of espionage against the United States and its allies, which would continue until the 1970s. If promoted from classifying and categorising fingerprints, female employees would spend most of the war getting vital information and military secrets into the right hands to keep the war machine running.

Photos by George Skadding for Life magazine (c) Getty Images

Photos by George Skadding for Life magazine (c) Getty Images

They worked 10 hour days, six days a week, processing upwards of 35,000 prints in total in a single day. Their salaries were paid by war bonds, the same bonds they were endlessly encouraged to buy.

Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5” is starting to play in my head.