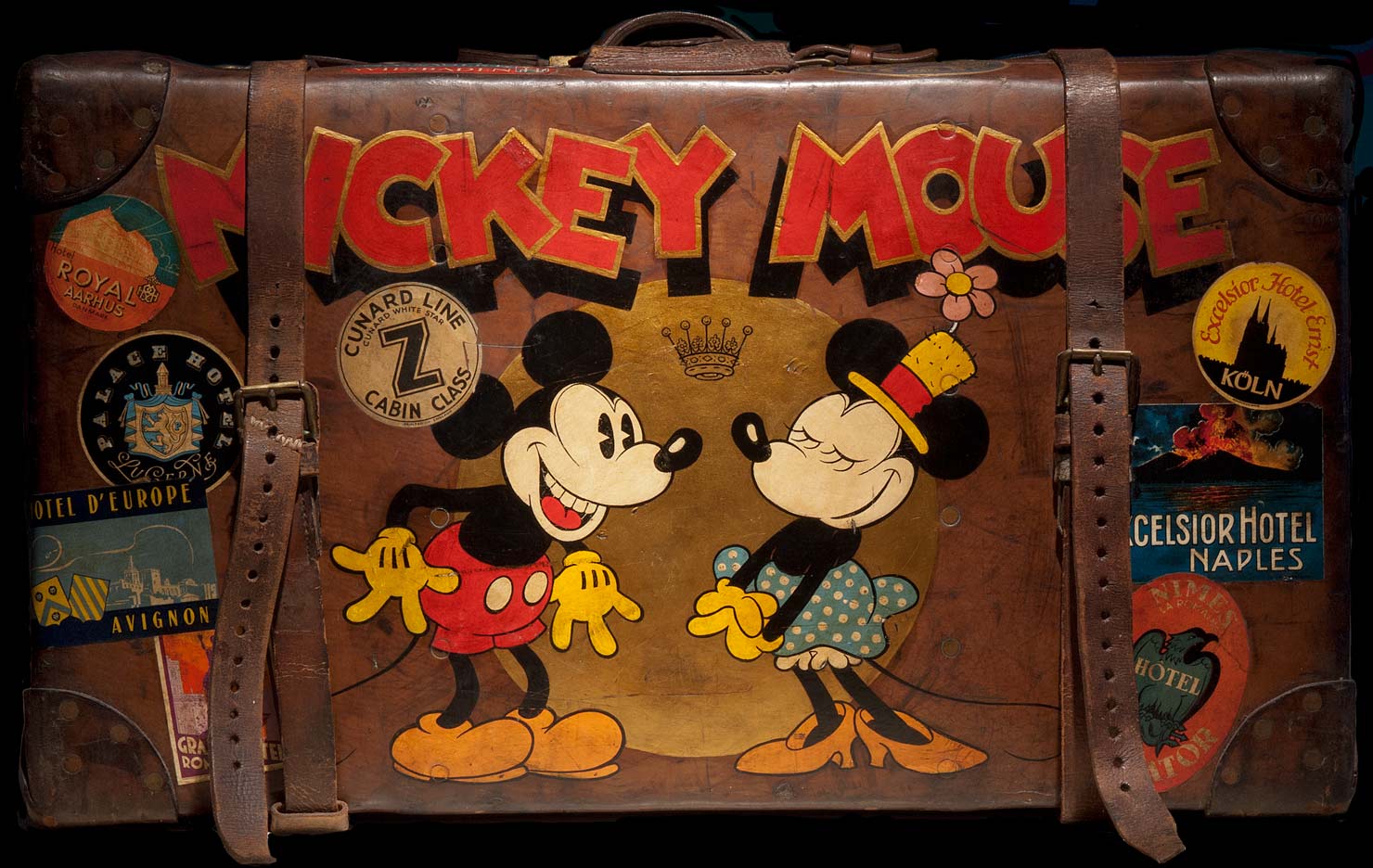

What is it that makes someone start a collection which alters the course of their entire life? For Mel Birnkrant, it was an iron Mickey bank he saw at the Paris flea market in 1958. His hotel room rent was $30 a month and the toy was $10. It was in that moment, at the iconic Marché aux Puces, that Mel was first bitten by the collecting bug. It would take him many more years to understand how that toy had such power over him.

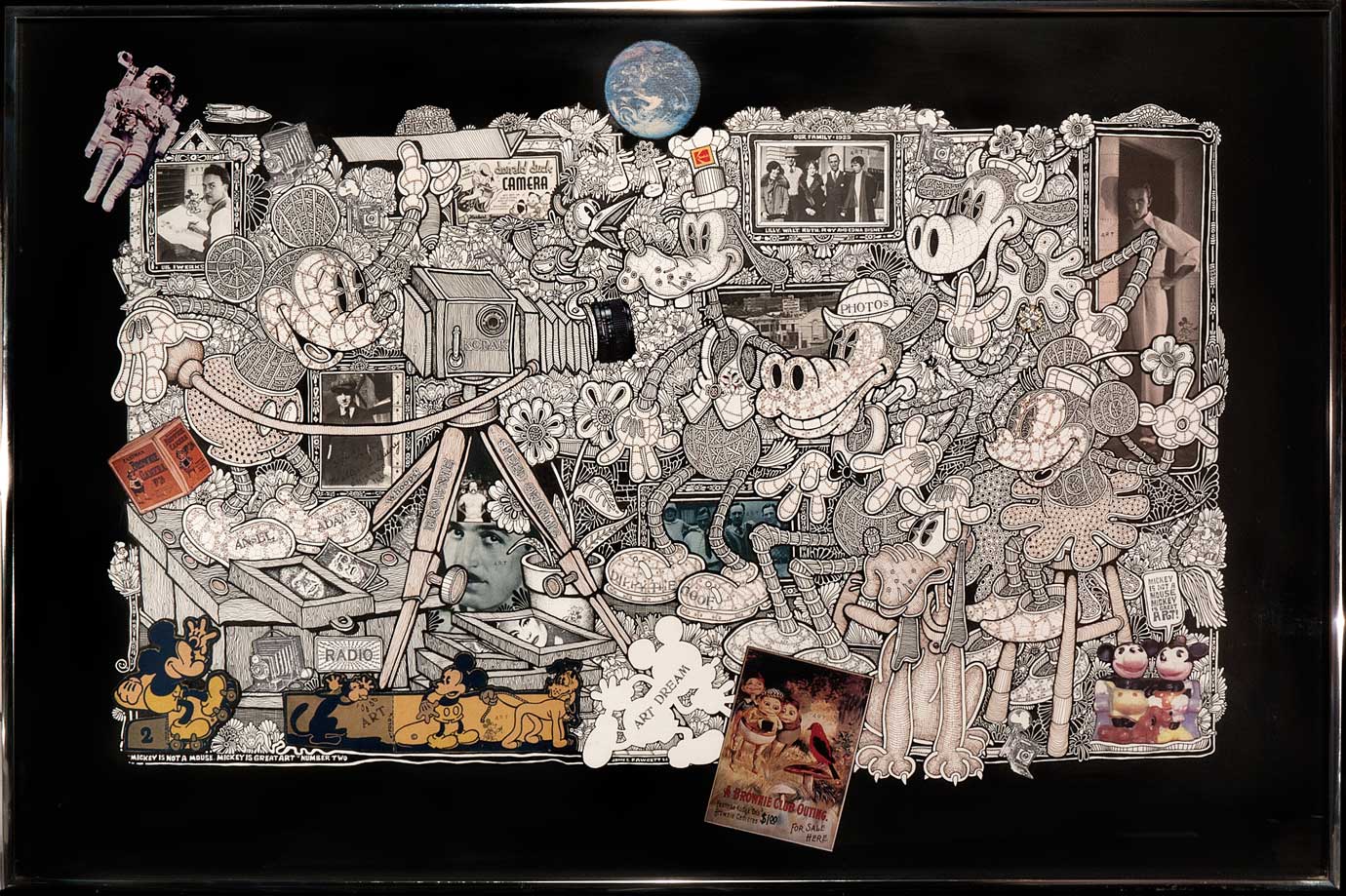

The purchase spurred a lifetime of toy collecting, turning objects not intended to be “art” and elevating them to that very level. “This simple act of recognizing that this object I had found was art, in 1958, when to all the rest of the world, it was not, and standing behind my conviction by paying what was, then, a painful price, I experienced all the emotional satisfaction that I would have if I had actually created this powerful object myself,” writes Mel. “Recognizing the visual merits of humble works, intended merely to amuse children and later be discarded, became, for me, an act of creativity. I could sense my entire body tingling, and, ever so slightly, levitating.”

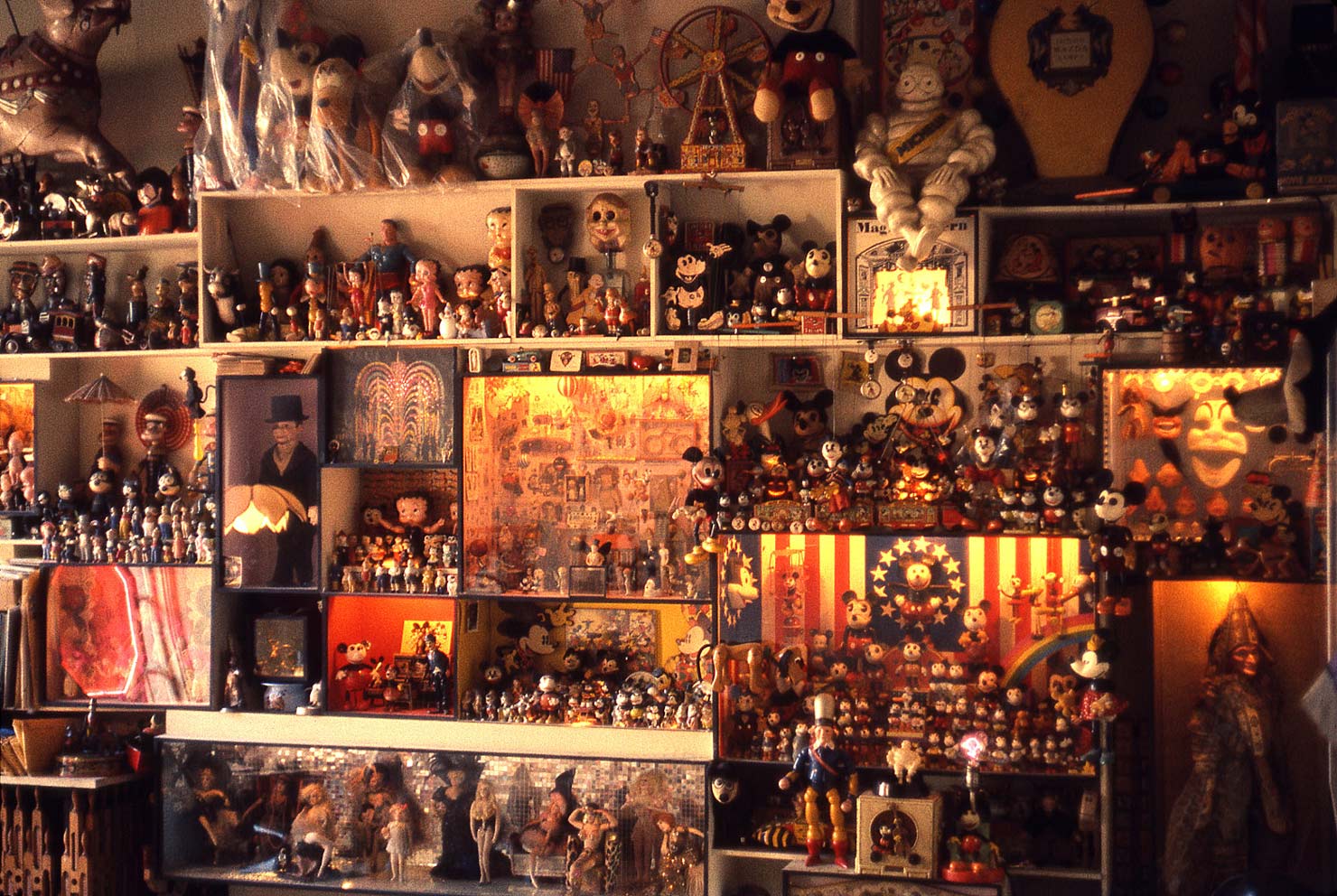

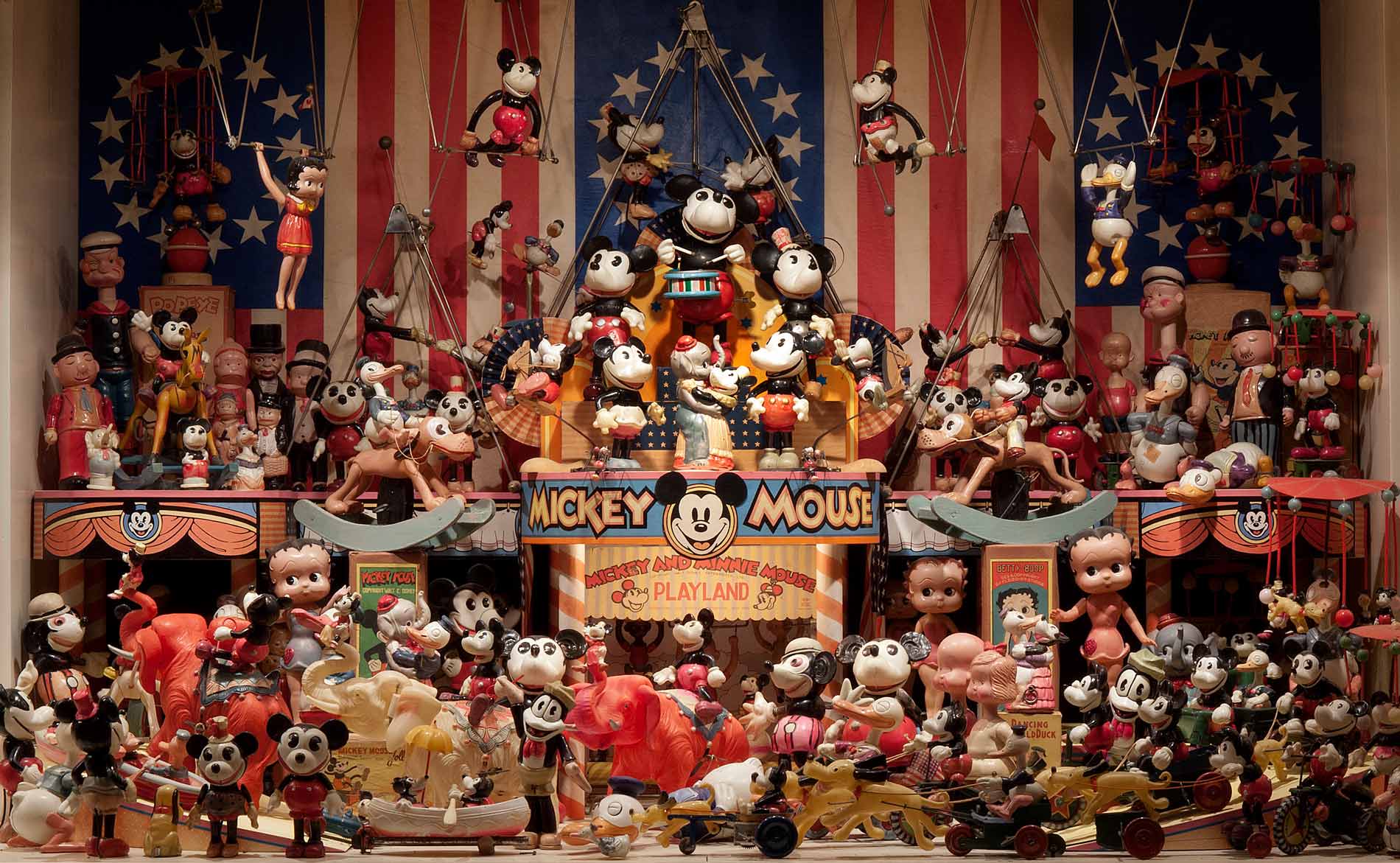

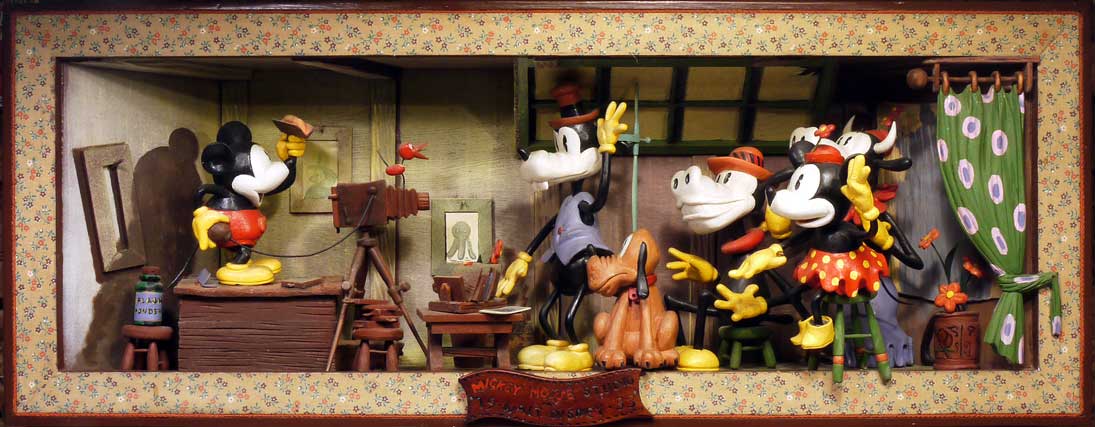

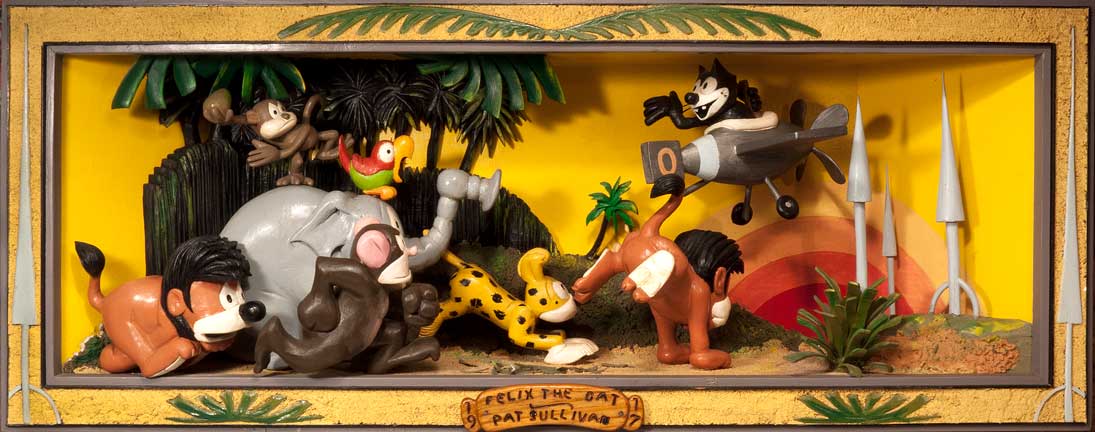

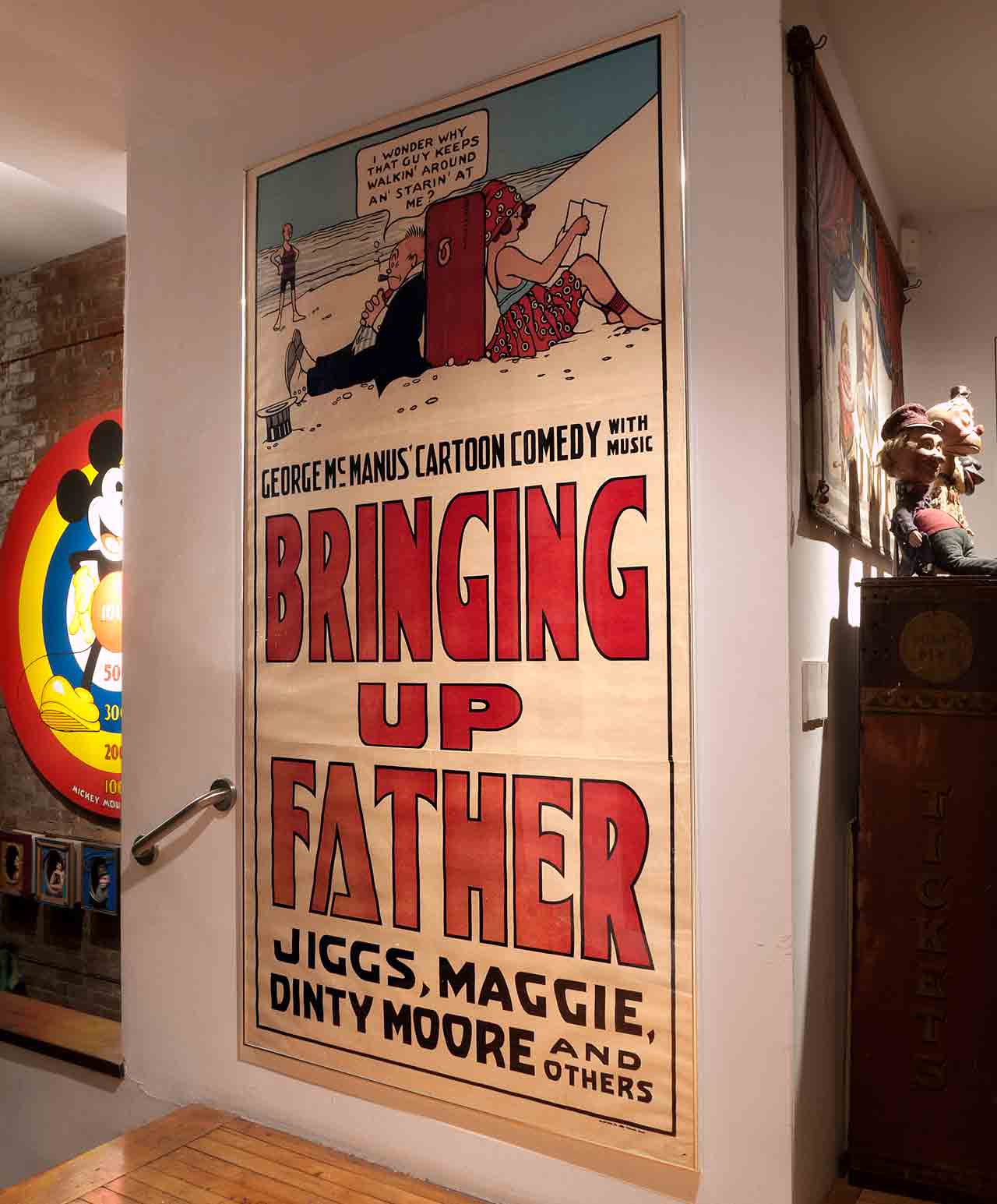

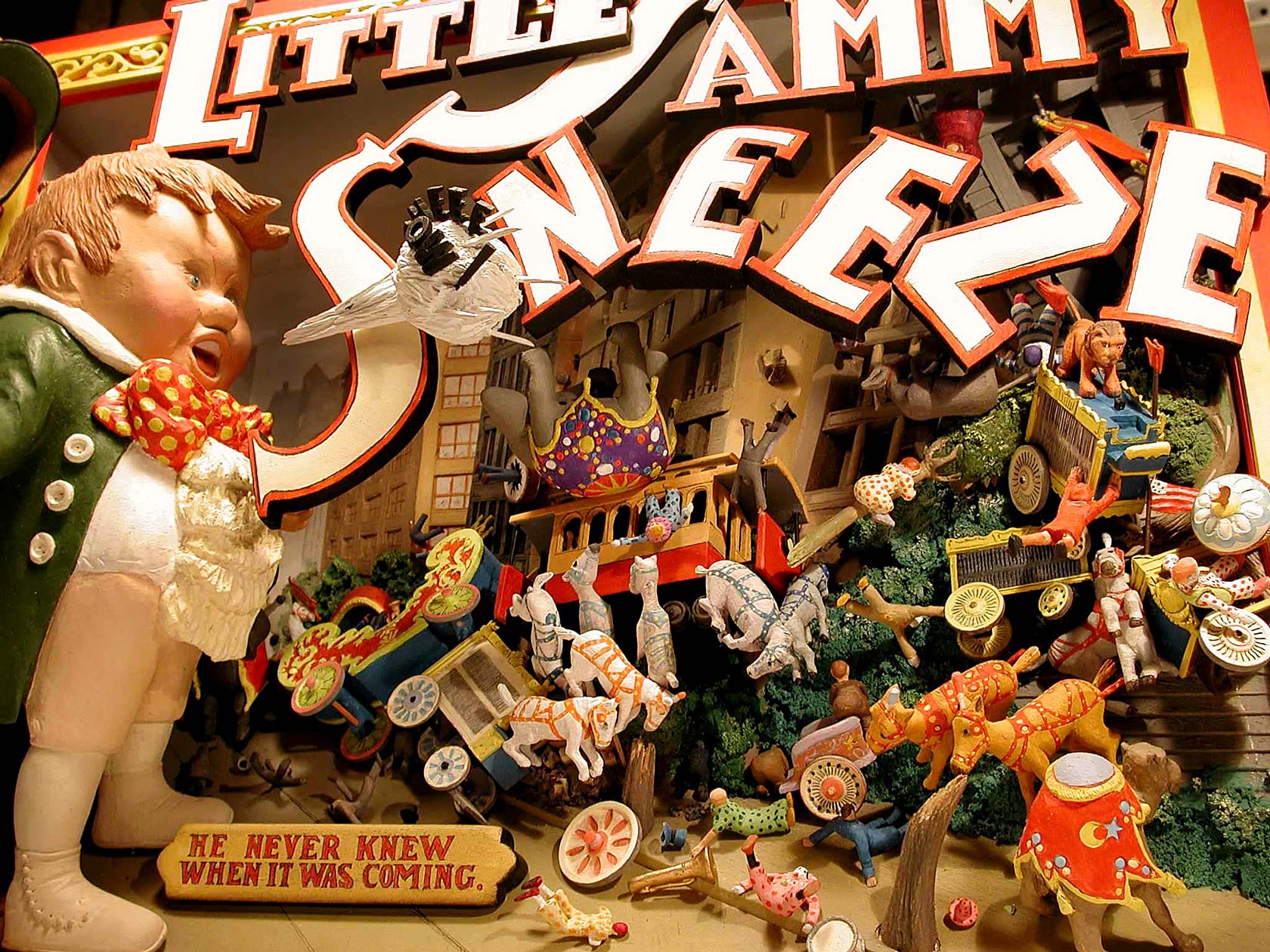

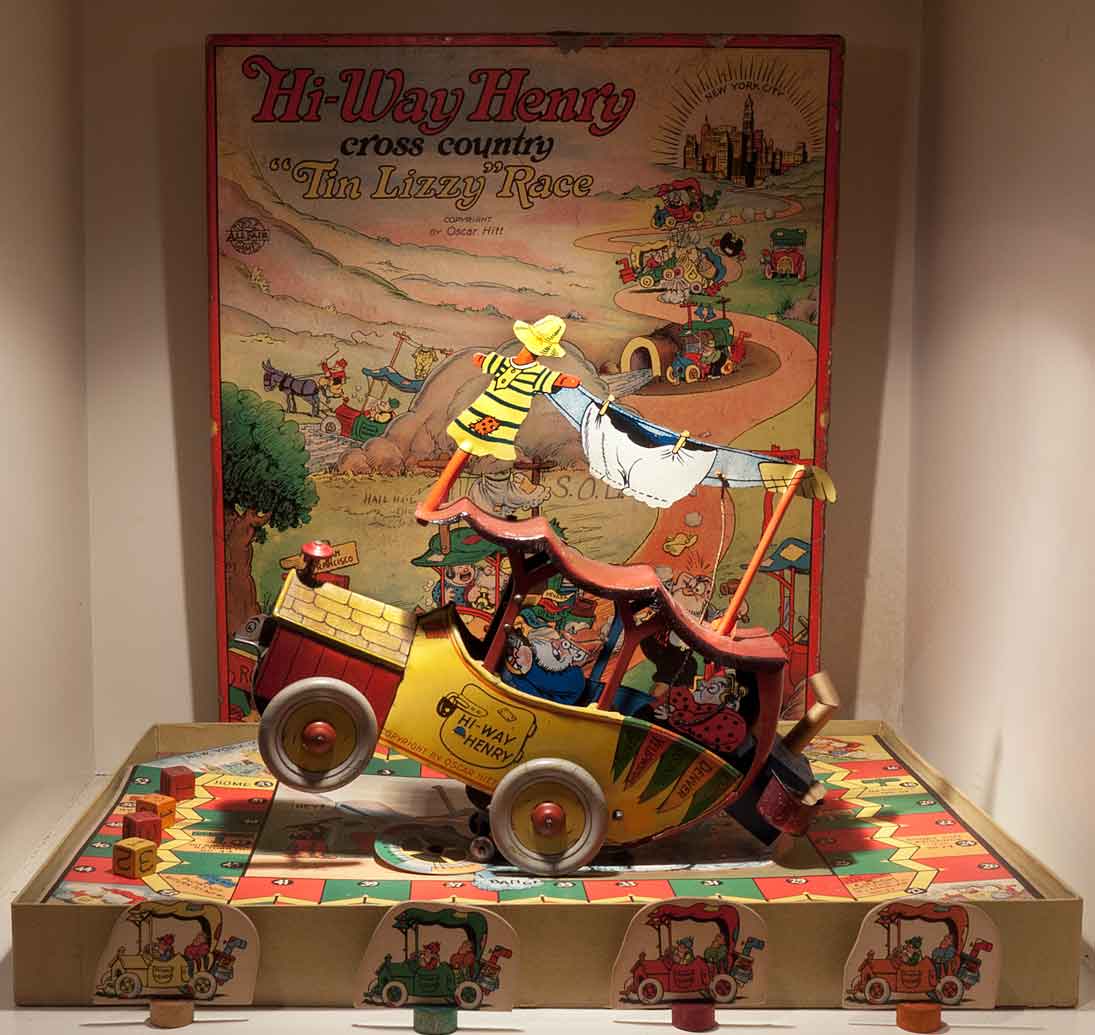

Mel’s private collection in his home in upstate New York doesn’t seem of this earth. It’s impossible to wrap your brain around the idea that this “Mouse Heaven”, as he calls it, a mind-boggling museum of Mickey Mouse and other toys of pre-World War II comics characters, was created by just one man. It is a genius work of lost art, a museum of dreams.

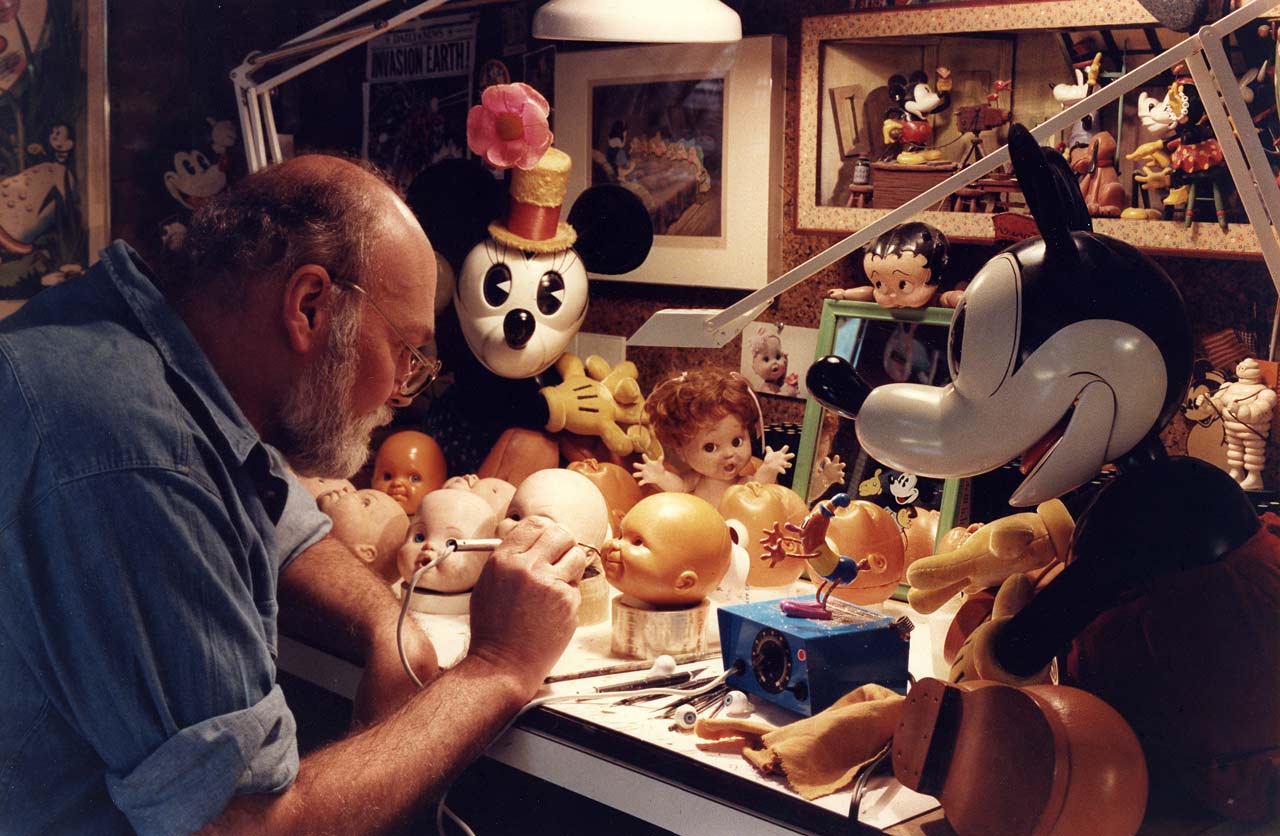

There is no doubt Mel Birnkrant is an artist in the same way that Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein are artists– Andy with his supermarket products and Roy with his old comic books. Mel also made toys himself over the years and invented the iconic Baby Face doll as well as The Outer Space Men action figures. From 1964 to 1986, Birnkrant designed toys for the Colorforms company.

Birnkrant grew up in Detroit following World War II, the son of a wealthy Jewish real estate mogul. In 6th grade, Mel was 6′ 4″ and weighed 260 lbs. He tried desperately not to stand out and rejected his parents’ lifestyle and values. “I struggled all my life to avoid contacting that newly named disease that I identified in my youth, now called, Affluenza. So, I made a concerted effort to avoid monetary success, at all costs”.

As a young man, he set off for France to “see (and do) art”, enrolling at the Académie Julian in Paris.

Of course, I connected most with his memories of my city…

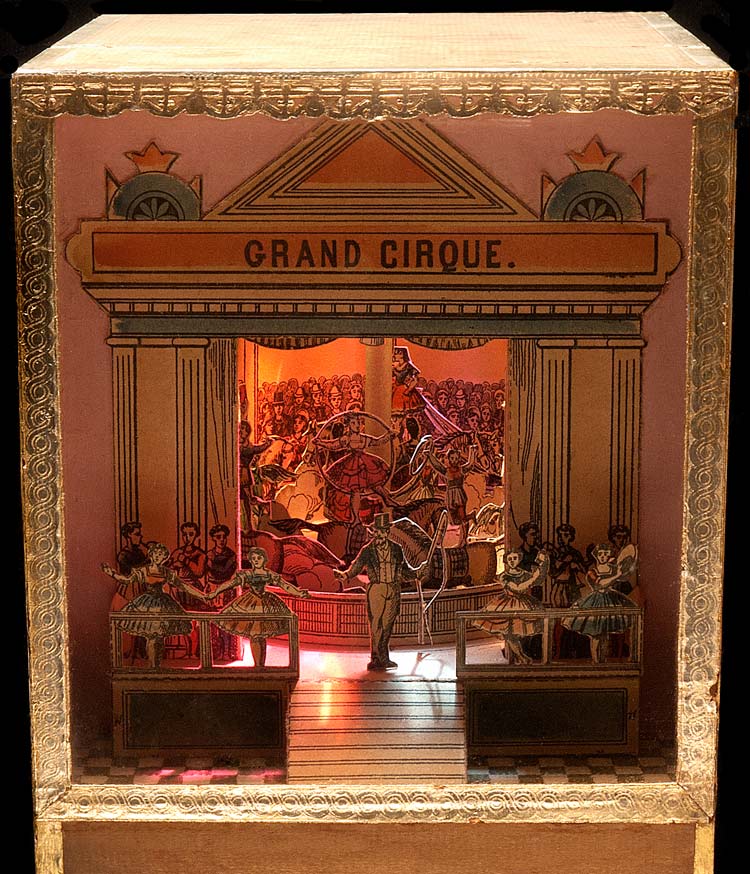

The art I saw was not found in the museums and galleries, but rather in the quaint shops, open air markets, and stalls, along the quays. Just along Rue Mazarine, a block away from my hotel, was the most phantasmagorical of shops, “La Librarie Labarre”. Monsieur Claude Labarre, was an Englishman, who had lived all his life in France. As a young man, he had been one of the inner circle that included, Picasso, Hemmingway, F. Scot Fitzgerald, and Henri Matisse.

Along with them, he regularly frequented Saturday night soirees, at the Salon of Gertrude Stein. He was readily inclined to reminisce with a customer, who could speak English, and I spent hours in his store, eagerly listening to his stories, and marveling at the artifacts on display.

The best way I can describe the contents of la Librarie Labarre would be to equate it to George Mêlées’ toy stand in le Gare Montparnasse, as portrayed in the movie “Hugo”. And each time I visited, I never left without, at least, a sheet, or two, or more, of images d’Epinal … These fabulous hand colored, paper cut outs … from fantastic toy theatres … to vehicles, ships and airships, and every form and shape of building, both fantastic and historic…Slowly but surely, I acquired several hundred images d’Epinal. I still have them all.

Mel can’t tell you how many objects are in his collection. He doesn’t believe in counting. And why Mickey? Funnily enough, he doesn’t particularly like his character, and he’s mostly drawn to the forms of his toys rather than their stories or personalities. “Mickey Mouse only interests me as three circles. Something you can draw with a quarter and two dimes. I can’t stand his little voice. Most Mickey Mouse collectors love goddamn Mickey Mouse. I love three circles and the fact that it looks alive.”

The effect his collection has on people, is not lost on Mel. Whether you’re one of the lucky few who gets invited inside his kingdom somehow or discovers it through Mel’s masterfully constructed online museum, your jaw will drop, vision will blur. He knows his collection is prodigious, priceless and comes with a responsibility to ensure it is preserved after he’s gone.

His website, which reads more like a book (in fact you can actually download it as an eBook), takes you on a journey from his earliest collecting days to present as he guides you around his endless display cases. Mel writes:

“A collection, like this, can only happen, once in a lifetime, and by some twist of fate, that lifetime happened to be mine. For better, or for worse, the likes of it could never be amassed again… To duplicate what you are about to see would require just three things: 1. Infinite resources. 2. A Time Machine, you’d have to be there, either living from 1890 to 1945, or be in attendance at all the great flea markets, antique shows, and toy shows on the East Coast, for the past 50 years, and be able to run faster than me. And, finally, 3. You’d have to BE me. All this only looks haphazard, actually, its unified by a single vision. Everything here is related, It all goes together, in a way that few perceive.”

The future of this kingdom, however, remains uncertain…

I’ve been exchanging emails with Mel over the last few days and was taken a back by what he told me. There was no beating around the bush…

“I’m afraid there really is no chance to save it; God knows, I’ve tried …Over the years, I had some lucky breaks, and a lot of bad ones too.” he wrote.

Mel seems resigned to the idea that after he’s gone, auctioneers will descend on his wife and daughter and “swoop in, like a flock of vultures. That’s the way it will be. The good news is that I will not be here to see it. Having spent my life, and all my creative energy, knitting this enormous sweater, I simply cannot bear being the one to un-pick it.”

To hear Mel talking like this, I immediately understood that his collection, as we know it now, is in danger. Mouse Haven is alive and vital thanks to the magician behind it. “It’s done with placement, settings and hidden spotlights that subtly guide the eye to what’s important to be emphasized … This great gathering of stylised imagery is the most complete compilation of this the first form of abstract (stylized) art the world will ever see.”

Once it is broken up and scattered, like Humpty Dumpty, “it can never be put back together again”.

So what are the solutions? I hoped to restore his faith and start up the conversation of how his collection can be guaranteed the future it deserves.

“I would sell it, in its entirety, in a heartbeat, to anyone who can, within reason, offer the hope and promise of keeping it together. That’s one of the reasons that I took the 1500 photos on my website, they would be a sort of guide as to how to display these things if they are acquired after I pass away. I’ll follow it to the ends of the Earth, to aid in setting it up, if needs be … a museum, or an archive, would do. It matters not where, Paris, New York or Timbuktu.”

Whoever gets this collection, clearly gets Mel too, orchestrator of the masterpiece, in person or in spirit. But to me, that would be one of the main motivations in being involved in its rescue. I’m worried there just aren’t enough people like him anymore in today’s world to teach, inspire and share such dedication for collecting, curating and preserving, and certainly if a work like this is in danger of being lost and dispersed, there’s an entire art form we’re imminently at risk of losing.

Nevertheless, I believe that with some renewed and fresh attention, there’s always the possibility of new doors opening.