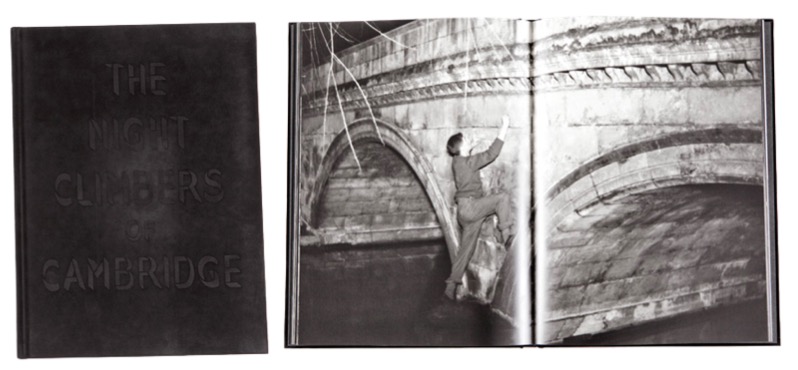

As night fell on Cambridge University in the 1930s, a dapper gang of undergraduate students regularly met in secret to climb up historical buildings, illegally exploring their campus via its rooftops and façades. They were known as the “Night Climbers of Cambridge”, immortalised in a cult guide book on the forbidden practice, anonymously published by the daredevil you see in the photograph above.

Like all true urban explorers, he had a pseudonym: “Whipplesnaith”, which also served as his pen name for the book that documented the group’s infamous clandestine climbing sessions.

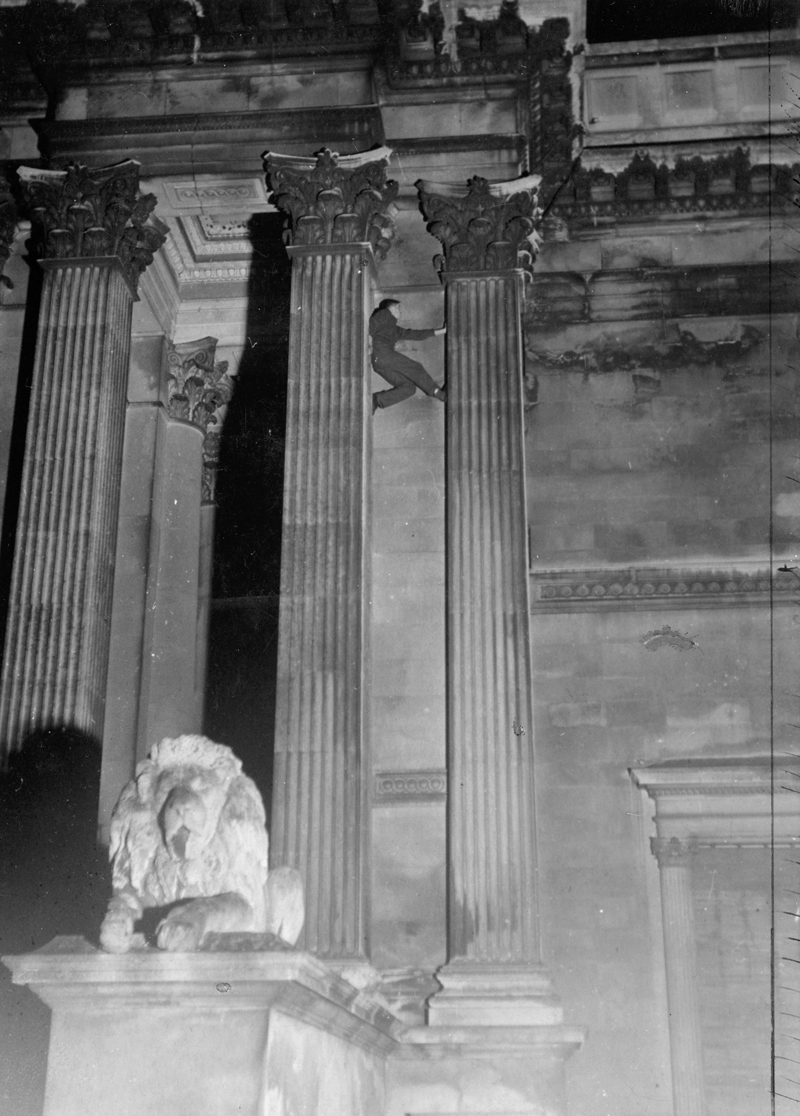

“This chimney, above one of the lions at the north-east corner, is of an ideal width with vertical grooves to keep the feet (and body) from slipping sideways.”

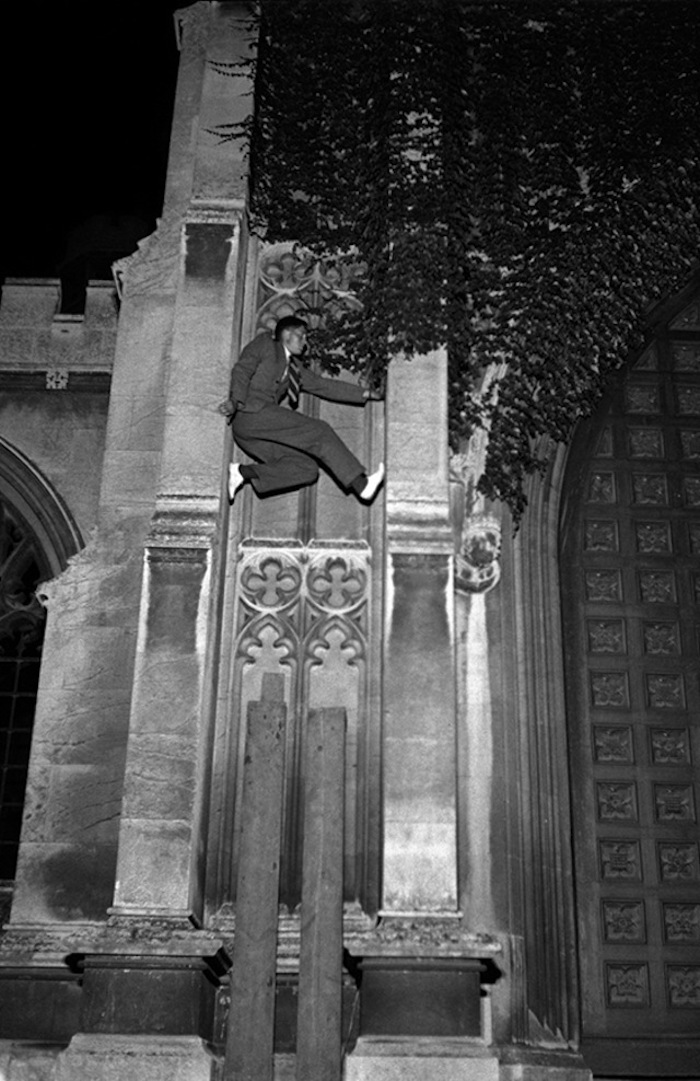

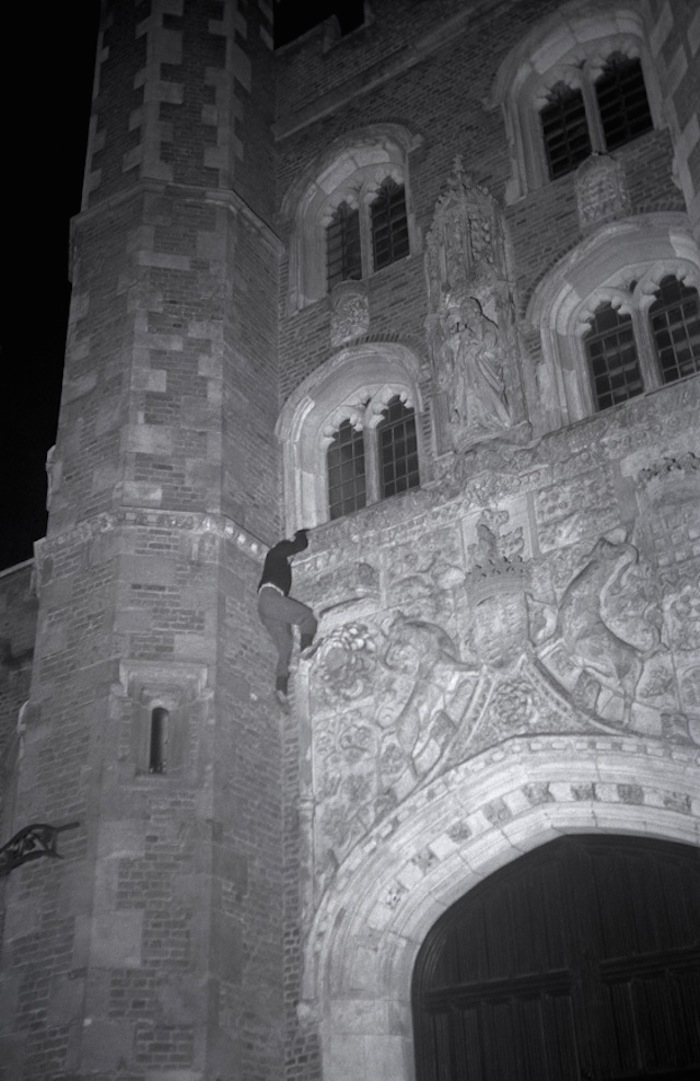

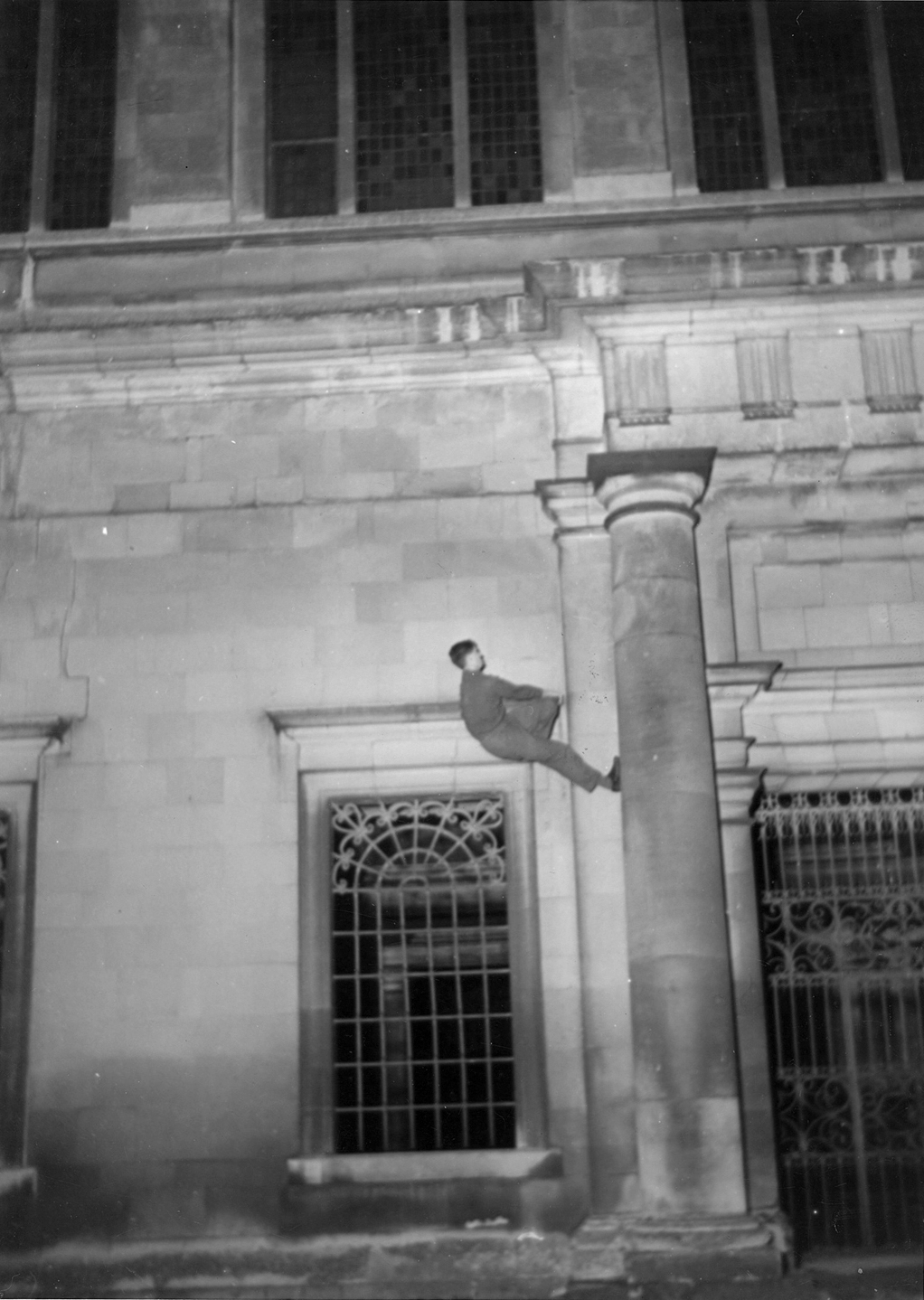

While one of the other members of the “club” was the designated photographer and another in charge of lighting, it was Whipplesnaith, the leader if you will, who was photographed in most of the precarious positions as high as 50 or 60 metres high, without a climbing rope, sometimes wearing a jacket and tie.

The Night Climbers of Cambridge was first published in 1937 by a reputable house that had also published the first English translations of Proust, but the unusual guide had a niche audience, and spent many long years out of print, collected only by a niche audience of climbing fraternities as an object of cult interest.

The more rare the book became, the more its legend grew, becoming highly sought after in later years, especially in Cambridge, where it was considered the holy grail of guidebooks on local urban exploration. Whipplesnaith himself, who we now know as Cambridge student, Noël Howard Symington, wrote comprehensive rooftop travelling tips to accompany the photographs, providing true and practical information in his notes for anyone else brave or foolhardy enough to climb the ancient university buildings– which probably explains why nocturnal climbing is still a thing on campus to this day.

“Chapel Spire: First overhang, with clover leaf above and below”, writes Symington. “Chess-board, at which point the stone becomes crumbly… the rest of the way up the climb is safe.”

“Pillars rear up at the outside corners and are joined to the Tower by an arch of sloping stone, festooned on the upper side with ornamentations that should not be trusted too far.”

Although this covert band of fearless students met regularly during their time at university, there were no societies of roof-climbers to regulate behaviour and keep the score.

In 2007, marking the 70th anniversary of the original edition, a new authorised edition of The Night Climbers of Cambridge was published, bringing to light once again the forgotten nocturnal antics of students climbing the iconic English university’s buildings in the inter-war years. Despite major book stores deciding not to stock it, the 2007 edition of the cult climber’s guide has still sold several thousands of copies.

Then in 2013, a French artist came along who had bought the entire archive of photographs in The Night Climbers of Cambridge from the son of Noël Howard Symington (Whipplesnaith). Thomas Mailaender, a contemporary artist based between Paris and Marseille incorporated the vintage images into a truly unique and interactive installation– and certainly the first art exhibition ever to require climbing shoes.

Not your average photography exhibit, the artist challenged visitors to actually scale a climbing wall themselves, just like the 1930s Cambridge students, in order to see all the photographs.

Thomas sees the Cambridge climbers as a group of young guys who were just utterly bored and tired of their role in society, so much so that they were willing to take risks not just with their places at Cambridge University, but with their lives. And let’s not forget these photos were taken in the midst of the depression in the 1930s.

The temporary climbing experience designed by the artist for galleries in England and France kept things authentic by not providing safety equipment. I’m guessing this really helped the viewer relate to the subject.

A quote from Whipplesnaith’s musings:

“As you pass round each pillar, the whole of your body except your hands and feet are over black emptiness. Your feet are on slabs of stone sloping downwards and outwards at an angle of about thirty-five degrees to the horizontal, your fingers and elbows making the most of a friction-hold against a vertical pillar, and the ground is precisely one hundred feet directly below you. If you slip, you will still have three seconds to live.”