This is the story of that time the United States decided to influence countries “at-risk” of falling to communism … by introducing them to jazz. In a Cold War “Jazz Ambassador” initiative, they sent famed artists such as Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Galespie, and Duke Ellington, among others, to share “their Western music” and to hopefully, introduce some American political ideals. Part of this initiative was also an attempt to make people believe that America was treating other races well at home. During the height of the Civil Rights movement, this attempted ruse didn’t always go down too well, particularly with the African American musicians serving as goodwill ambassadors. Nevertheless, government officials recruited the most popular jazz names of the day and enlisted their talents to use in service of their country. They were sent to all corners of the globe, even behind the Iron Curtain and wherever the US government felt it was necessary to spread America’s “democratic culture” in the face of communism.

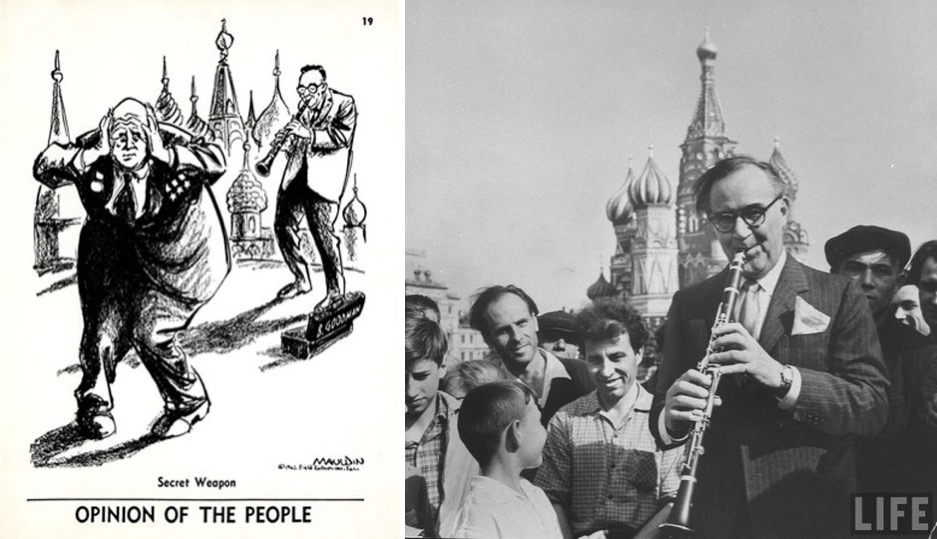

Left, a satirical cartoon of the”King of Swing”, Benny Goodman, in the USSR © Bill Mauldin. Pictured right in Moscow by LIFE.

Dizzy Gillespie and his band in the Dominican Republic, 1956, a decade before the US would invade the country to prevent it from becoming a Communist dictatorship

Benny Goodman “King of Swing” on his tour of the Far East in 1956 © Yale University

The State Department’s first official jazz ambassador was Dizzie Gillespie. Here he is pictured riding around the streets of Zagreb, Croatia during an official government tour with a Yugoslav composer, Nikica Kaogjera in tow. Dizzy’s introductory “mission” began in 1956 when he was sent to Athens, Greece, a country the US believed was among those at risk of falling to communism “like dominoes”.

This was only a few after the Greece’s ruinous civil war between communists and republicans that had left the country’s numerous communist supporters on the losing side.

Ironically, Dizzy was a personal and favourite friend of Langston Hughes, the pioneer of jazz poetry, who in the early 1950s, had been grilled by Washington alongside other creatives in secret testimonies for their “communist-like” ideals.

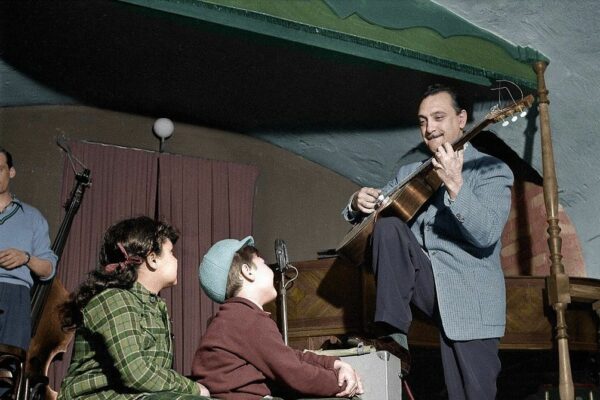

Louis Armstrong, nicknamed “Satchmo”, followed in Dizzy Gillespie’s footsteps with an unofficial trip to the British Gold Coast colony (which became an independent Ghana one year later). Several hundred thousand people turned up as Armstrong trumpeted his way across the country. Afterwards, Louis became the most active ambassador, on both official and unofficial tours. His 1960 tour was so rigorous and demanding that accompanying singer, Velma Middleton, suffered a stroke in Sierra Leone where she passed away one month later at the age of 43.

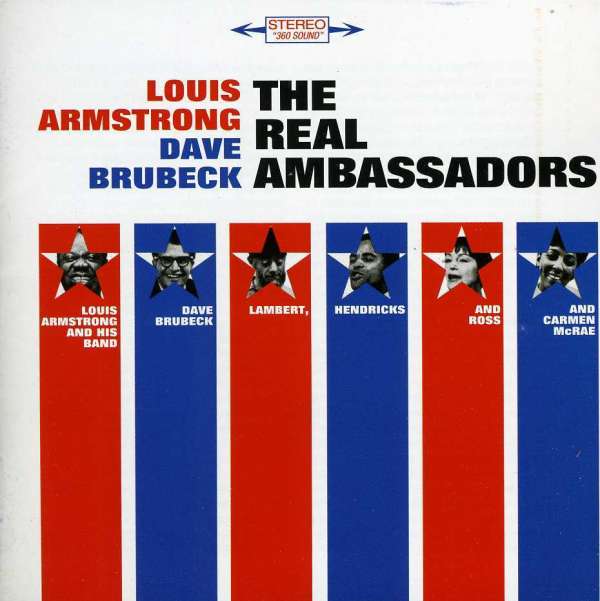

The State Department would often cancel the artists’ commercial tours back home without their approval, in order to extend their international tours. Satchmo once toured for 160 days straight, and Dave Brubeck for 120.

The irony of sending black musicians to countries where they experienced greater equality than in their home nation was not lost on Satchmo. It was no coincidence however, that this ambassadorial program had taken off during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. The government had not only begun this program to spread American ideals, but also, primarily, to improve its image in a world that recognized the country’s racism.

The program was initiated just one year after a Supreme Court ruling declared racial segregation in schools as unconstitutional. Slated to tour in the Soviet Union in 1957, Armstrong defiantly refused the tour when President Eisenhower sat idly by as Arkansas defied the Supreme Court’s ruling on segregation. That same month, Satchmo famously stated: “The way they’re treating my people in the South, the government can go to hell.”

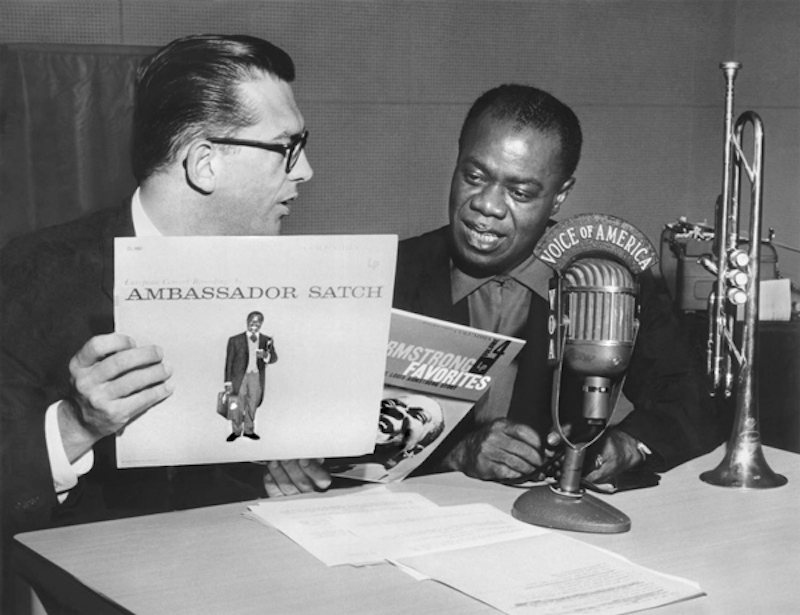

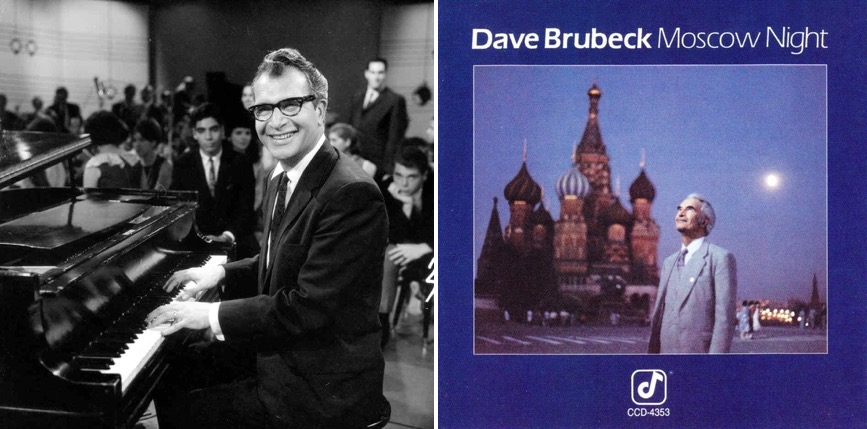

Armstrong and fellow ambassador, Dave Brubeck, made more waves in their support of Civil Rights in the early 60s when Brubeck and his wife, Iola, created a musical satirizing the entire program. They called it “The Real Ambassadors,” and it starred Satchmo, himself.

Dave Brubeck said the point of their satire was to make people laugh at the “ridiculousness of segregation,” but instead of laughter, they found that people were deeply moved by it. It even brought Louis Armstrong himself to tears– especially after a song that repeated over and over, “God created us in his own image and likeness.”

Brubeck famously toured much of the Soviet bloc and its surrounding countries on state sponsorship. During the height of the Cold War, he filled a concert hall with 2,500 Soviet audience members in Moscow, where American jazz had been denounced by Kremlin conservatives as “revolting rubbish” and “ideological poison”. You can listen to Brubeck talk about the jazz ambassador initiative on Youtube.

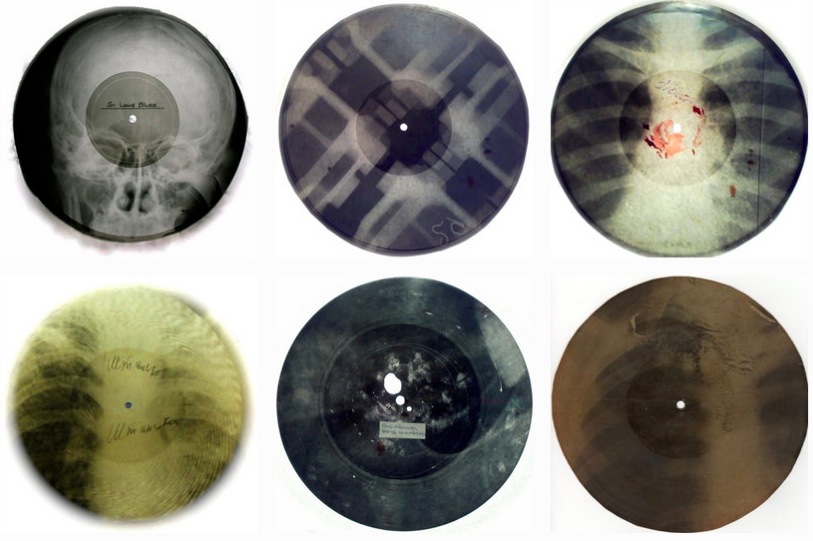

Prior to such tours, just listening to jazz in those countries could get a person sent to Siberia labour camps. If you wanted to risk buying a jazz record in the 1950s Soviet Union, you’d have to find the bootlegger who was selling “bones” (pictured above), illegal records cleverly made on developed X-ray film taken from hospitals.

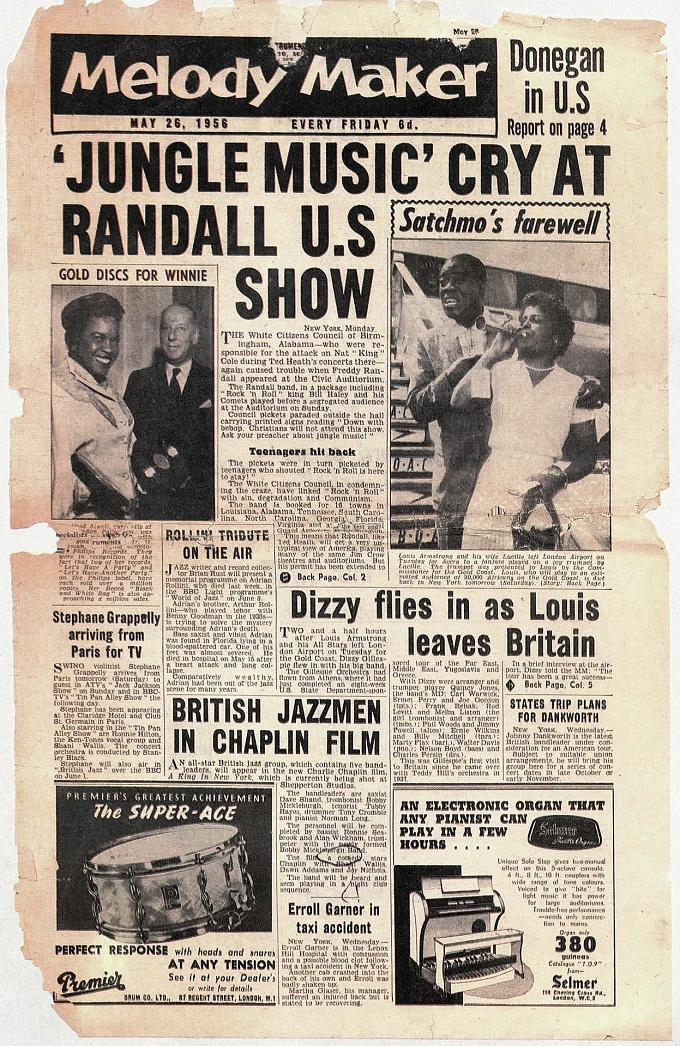

Even back at home on American soil, many criticised the growing “respectability” of jazz, but the tours demonstrated still further the revolutionary nature of the genre. The lead article above from British newspaper, Melody Maker in 1956, reminds us of the uphill battle that jazz still had to overcome on all fronts.

Free-spirited Soviets and Americans alike however, found it rebellious, as the artists and the people they reached used jazz to protest politics on all sides. It was the people’s music, belonging to everyone and no one at the same time.

These “Cold War Jazz Ambassador” tours continued through the late 70s when the Vietnam War nearly brought an end to the program. Jazz stars had played their way across the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Northern and Central Africa, and parts of Southeast Asia and South America. By the time the tours ended, they had reached millions, and the artists in turn had learned much from diverse populations. Brubeck found inspiration from the Polish and brought them to tears with a song inspired by the nation’s iconic composer, Chopin.

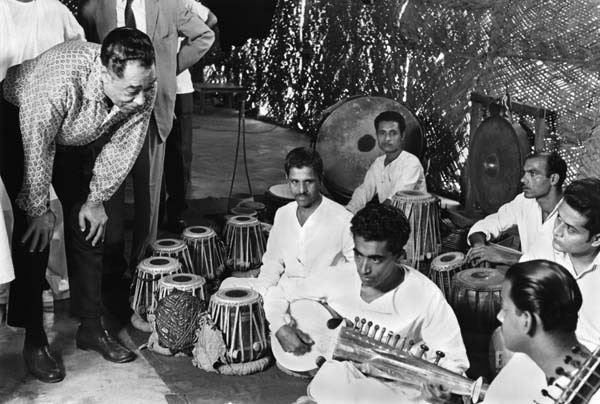

Dizzy was inspired by a boy playing a clay instrument in Pakistan, taking down every note he played and even included him in one of his band’s jam sessions. Louis Armstrong made a point to play at schools and sanatoriums, wanting to reach everyone.

Here’s the legend himself playing in Ghana in 1956:

Whether it accomplished the State Department’s official goals or not, the Jazz Ambassadors forged lasting connections with people around the world and cemented the cultural and political significance of the genre. As Louis Armstrong said in 1970 when asked what jazz is: “If you still have to ask, shame on you.”