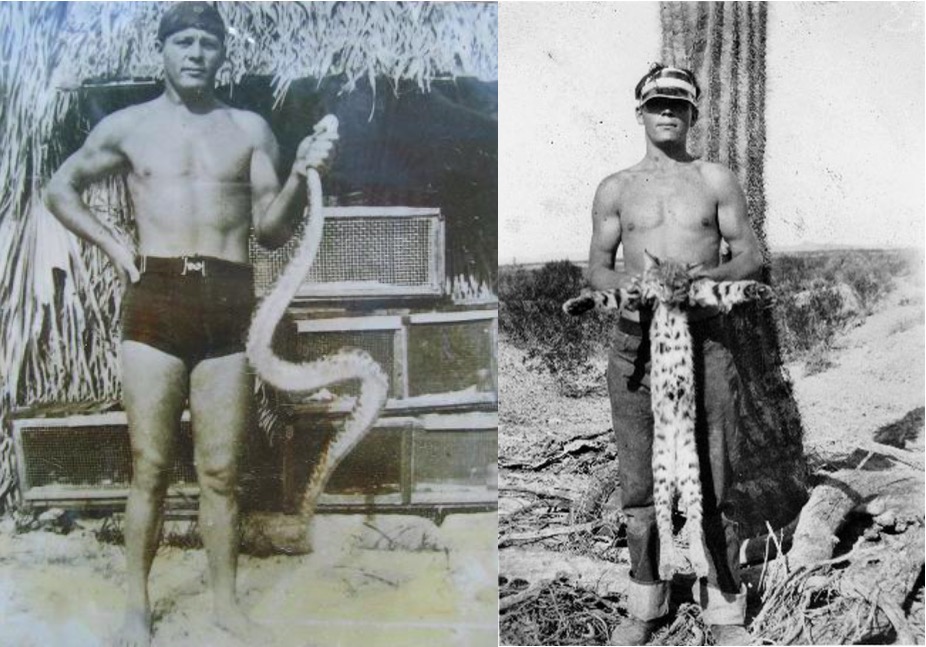

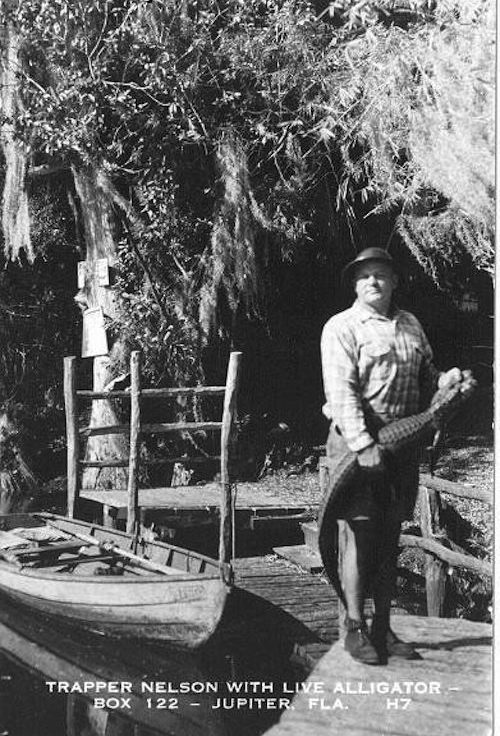

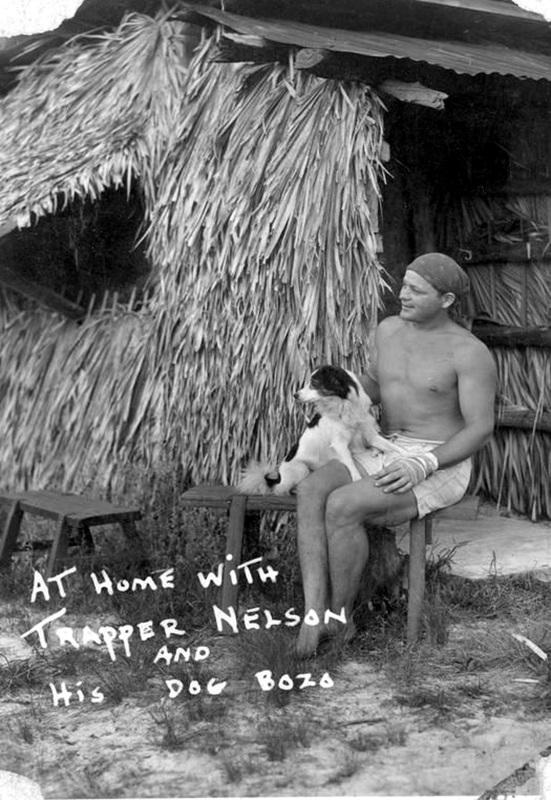

At 6’4” and 240 pounds, handsome, muscular Russian-American Vincent Natulkiewicz looked like he’d stepped out of a Tarzan movie. And like Tarzan, he lived in the jungle with his animals. Vince “Trapper” Nelson—or Tarzan of the Loxahatchee River—arrived in Hobe Sound, Florida, from New Jersey in 1930. He built a log cabin deep in the swamps (way before the strip mall-ification of modern day Florida) and created his own private oasis. Here Nelson roamed bare-chested and barefoot in a military helmet, trapping raccoons and alligators, and living off “wild cat stew.” We, uh, won’t include the recipe here.

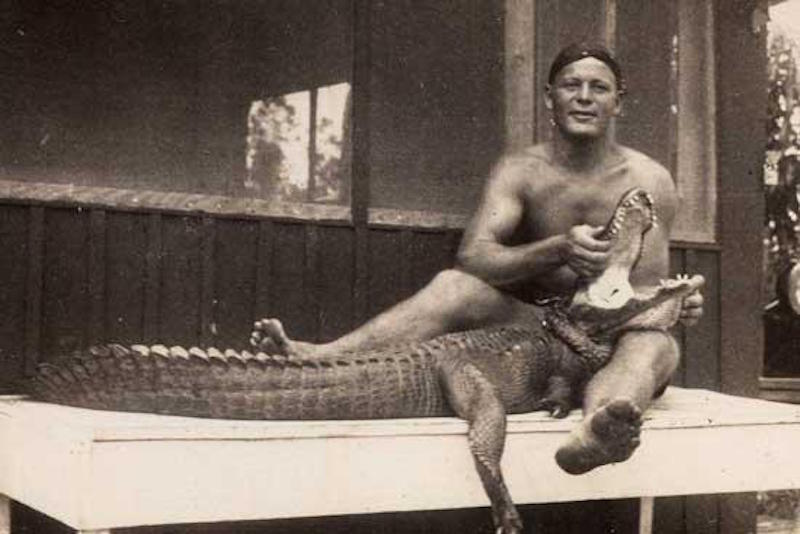

A young Trapper, holding his dinner.

After awhile, he opened Trapper’s Zoo and Jungle Garden where he displayed alligators in hand-made cages and rattlesnakes in barrels. Noisy guinea hens roamed freely. He’d drape snakes around his shoulders and wrestle alligators as part of the show—one time even jumping on one’s back and riding him up the river.

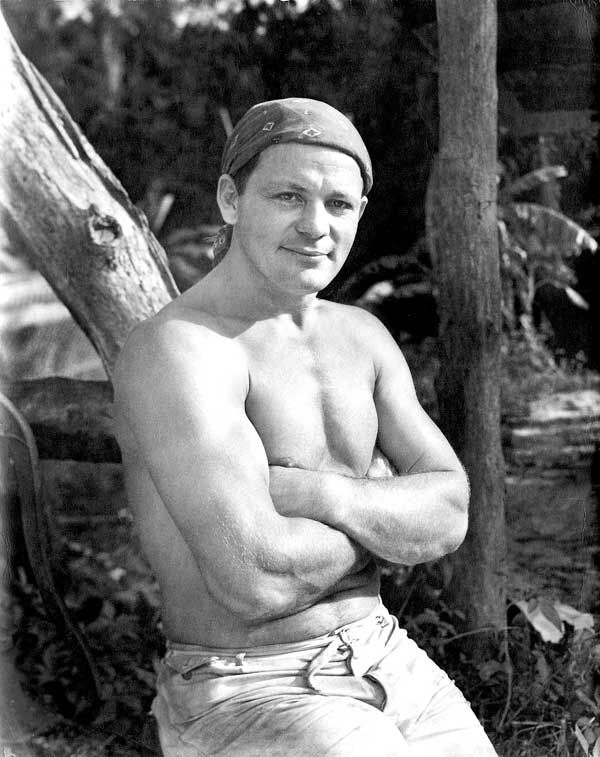

Bare-chested Trapper, lounging at home.

Tourists loved it, and Trapper Nelson quickly became a bona-fide legend.

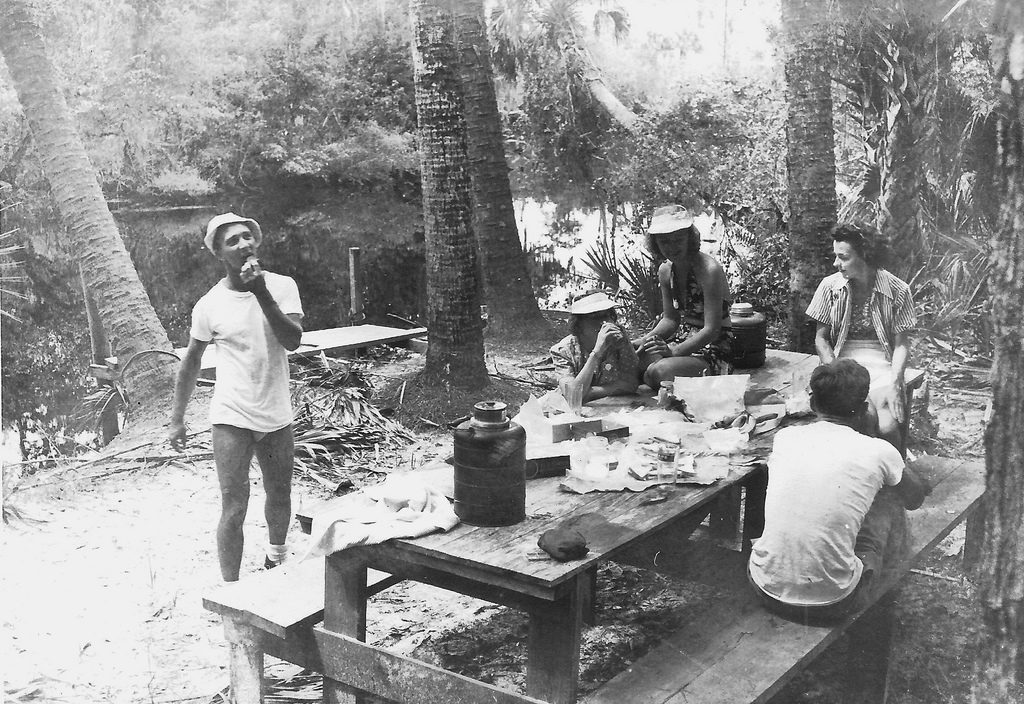

Tourists at Trapper’s Zoo and Jungle Gardens.

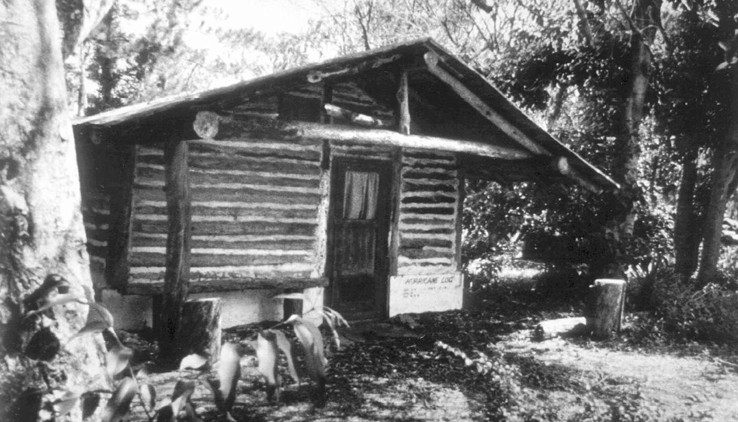

Trapper’s Camp in the 1940s © Alan Gathman

Visitors to Trappers camp in the 1940s © Alan Gathman

Rumors swirled of his gargantuan appetite. He ate entire boxes of chocolate bars, whole cylinders of raw honey, and entire pies. His appetites extended to women, too, especially society heiresses with real estate to their names who donated land to their backwoods Tarzan. Plus, he was smart enough to scoop up land at tax sales, so that eventually, his property with guest cottages and zoo encompassed nearly 1000 acres— larger than New York’s City’s Central Park.

Women, chocolate, and gators— a dream life, until the state of Florida intervened — first claiming he owed taxes, then deeming his zoo unsanitary. This was a disaster for Trapper, and he grew paranoid that there was a plot to take his land (shocker, there probably was.) After a while, he barricaded the road to his camp and required even his friends to send him postcards before visiting.

Trapper’s cabin, which still stands today.

Not too many years later, in 1968, friends found him dead from a gunshot wound to the chest. While the police hurriedly ruled his death a suicide (and the State did take his land, just as he had feared), most people thought it was murder. He had enemies, including his own brother, who, ironically, had just gotten out of prison for murder and blamed Trapper for putting him away. Maybe it was a robbery gone wrong, or the vengeful act of a spurned husband. Unfortunately, all evidence (including the gun, which was wiped clean of all fingerprints, including Trapper’s) was suspiciously inconclusive.

Inside Trapper’s cabin © Brent Sudeck

Trapper’s Gator Pit Today.

Today, you can visit Trapper’s preserved camp at the Jonathan Dickinson State Park, now eerily silent and view the remains of his cabins and animal cages.

Or, you can wait until dark and maybe then, like the tour guides and the couple who live nearby, you’ll see the shadow of a large man standing behind you, inspecting his camp.