In a stifling gymnasium in Anywhere, America dozens of couples shuffle around the cramped space clinging on to each other for dear life. Spectators in stands cheer on their favourite couples, watching their aching legs barely hold up their exhausted bodies. Some have mastered the art of sleeping on their partners shoulders; as long as they keep moving they stay in the game. Many couples have dropped out since they’ve started, but many remain, so they keep moving through sleep deprivation and pain. They have been at this for over a month, and yet the end is nowhere in sight.

On October 29, 1929, a dark shadow was cast over the bustling Jazz Age. Black Tuesday, the day the stock market crashed affecting rich and poor alike, sent the world into an economic depression, putting as many as 25% of Americans out of work. Dark, desperate times suddenly became a reality to those who enjoyed the over-indulgence of the roaring twenties.

The Dance Marathon originated in 1923, when a woman named Alma Cummings danced for 27 hours outlasting six partners. From there it bloomed into a full-blown craze where couples competed against others to be the last pair standing. Though the spectator sport began in a period of liberation (dancing in public was just starting to become socially acceptable), once the Great Depression hit those same competitions for fun and fame became desperately serious.

Much like the reality TV of today, the marathons were a combination of authentic endurance events and scripted stage shows. Professional marathon couples would enter and pretend to be amateurs, or else actors were hired to fight with other couples, blurring the line between reality and make-believe.

Even the way the competition was conducted ran like a theatrical production: an emcee would would work up the audience with tag lines like “How long can they last?” and even spun stories about partners in love, local favorites, and married couples who needed to win the cash to feed their children. Couples would even perform choreographed “coin dances” and the emcee would prompt the audience to rain them with a “silver shower”.

For all hubbub and toil of competing in a dance marathon, the cash prize was usually only around $500 (rarely thousands). The promoters made their investment back many times over, however, charging 25¢ admission from those poor from the depression and looking to pity someone besides themselves. Many promoters also had the reputation of going to “virgin” towns where they could run a marathon then skip town before paying the bill. This, paired with opponents like movie theatre owners who were losing money and women’s group who found the competitions immoral, made more and more towns dubious of hosting an event.

But towns weren’t the ones that suffered the most from the marathons. The anguish of dancing for weeks on end not only affected the body but the mind (the longest one lasted almost 6 months).

Seattle banned all marathon in city limits in 1931 when a woman attempted suicide after dancing for 19 days only to come in 5th place. Though the marathons were truly gruelling, in the desperate times of the Great Depression, it meant a roof over their heads and plenty of food (twelve meals a day in most cases), and the hope that they may win a cash prize furthered their desire to keep on shuffling along.

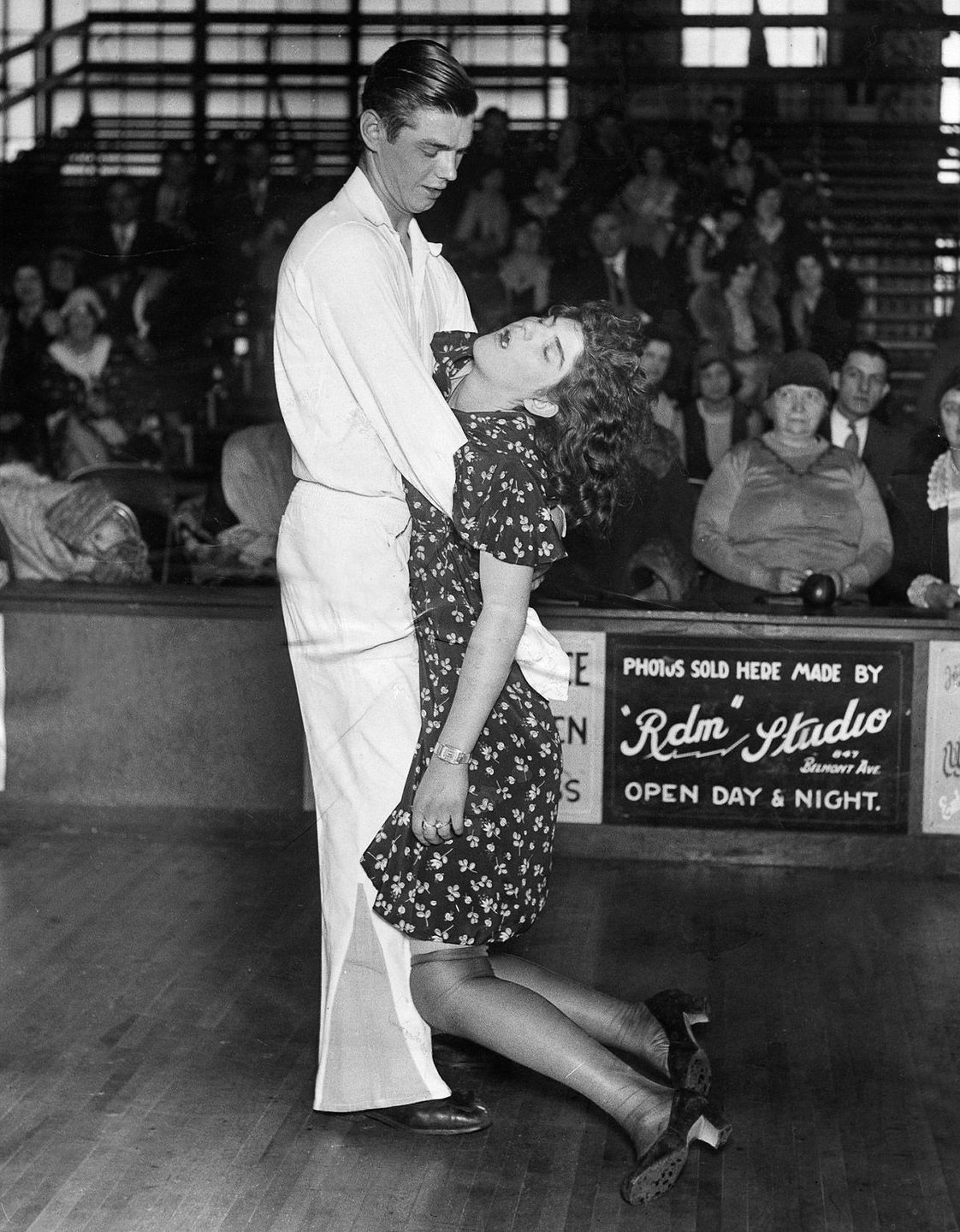

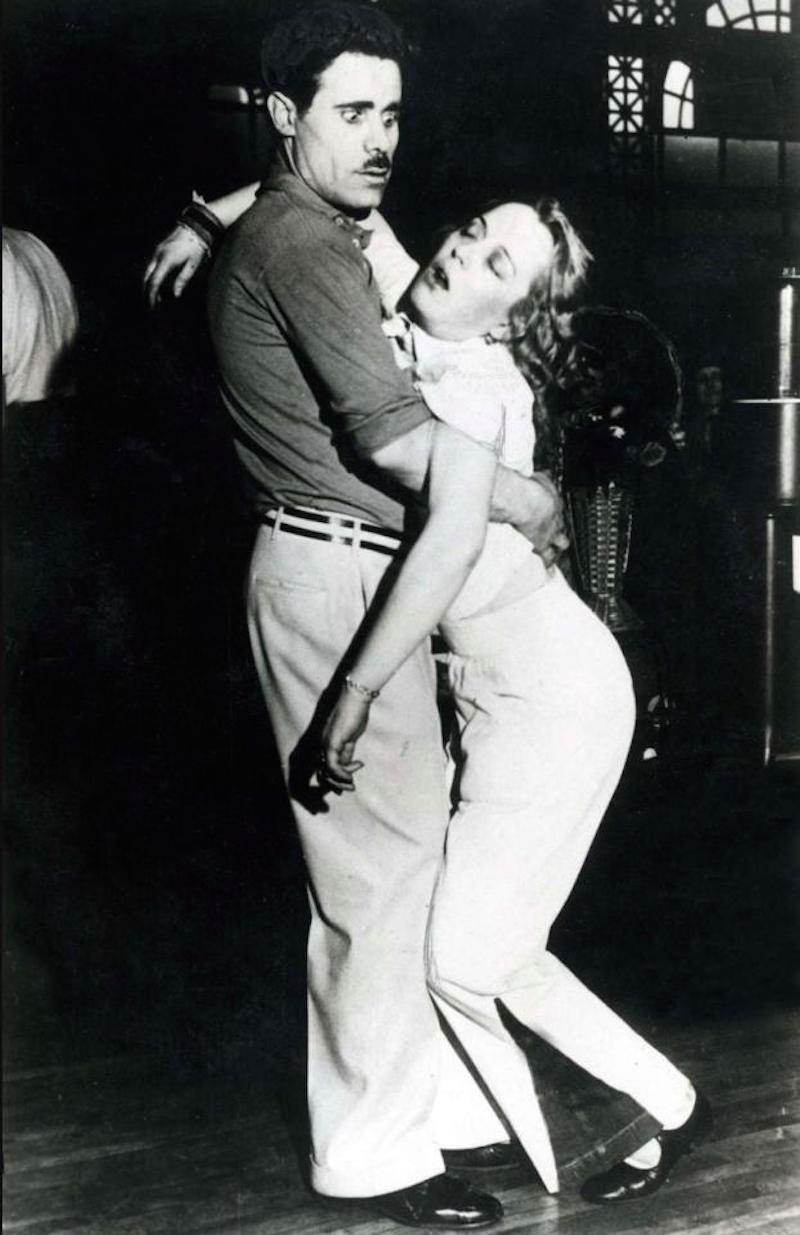

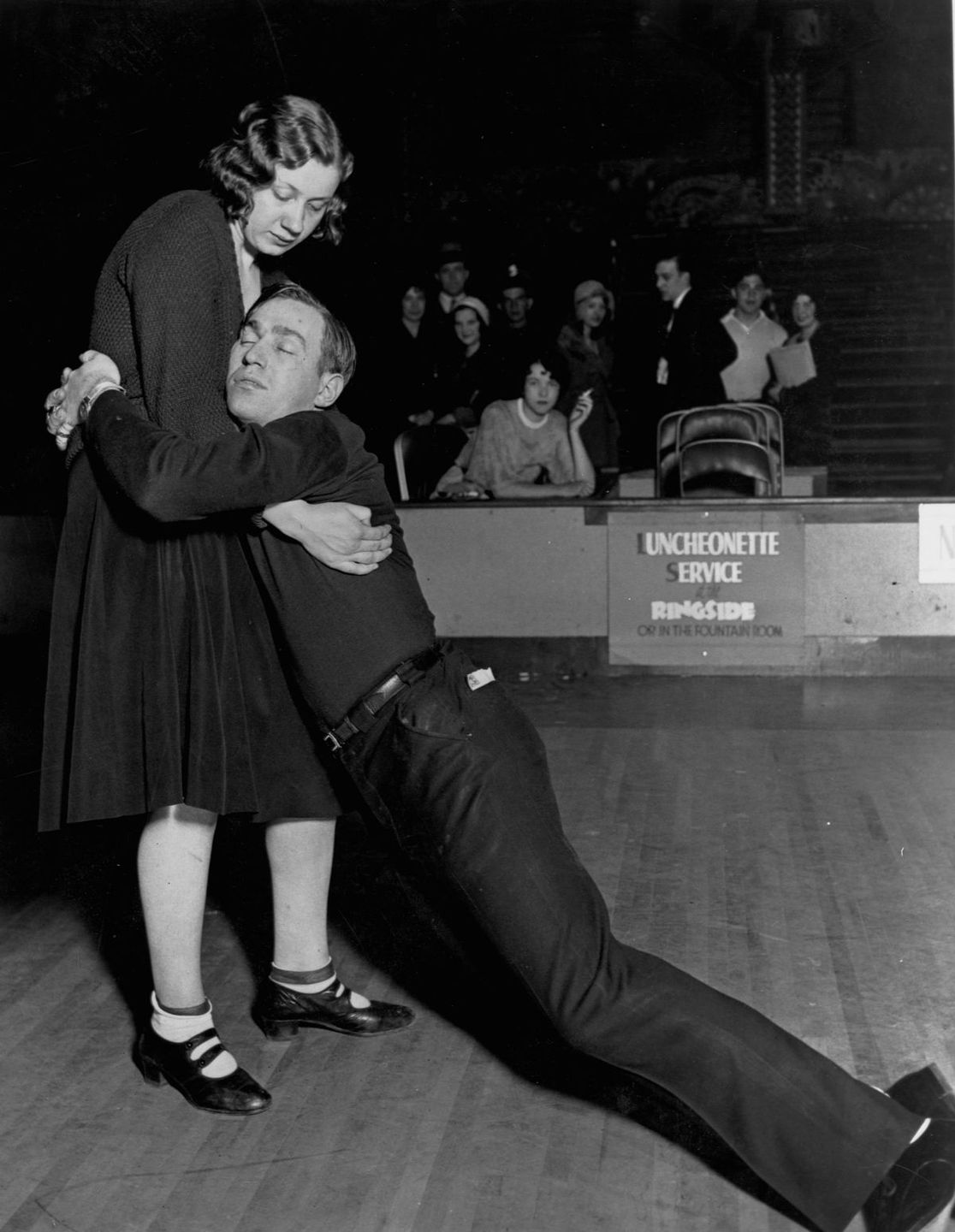

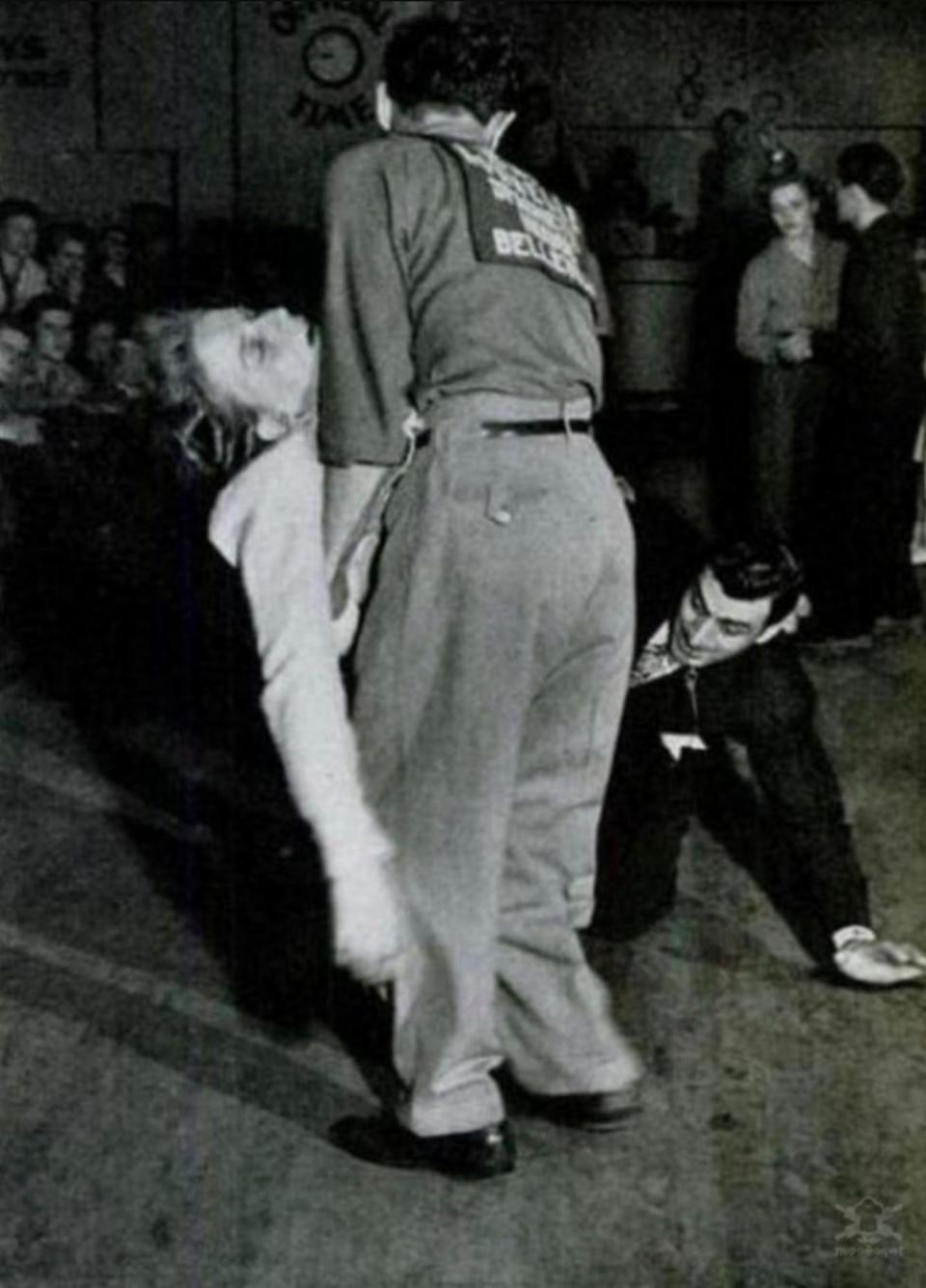

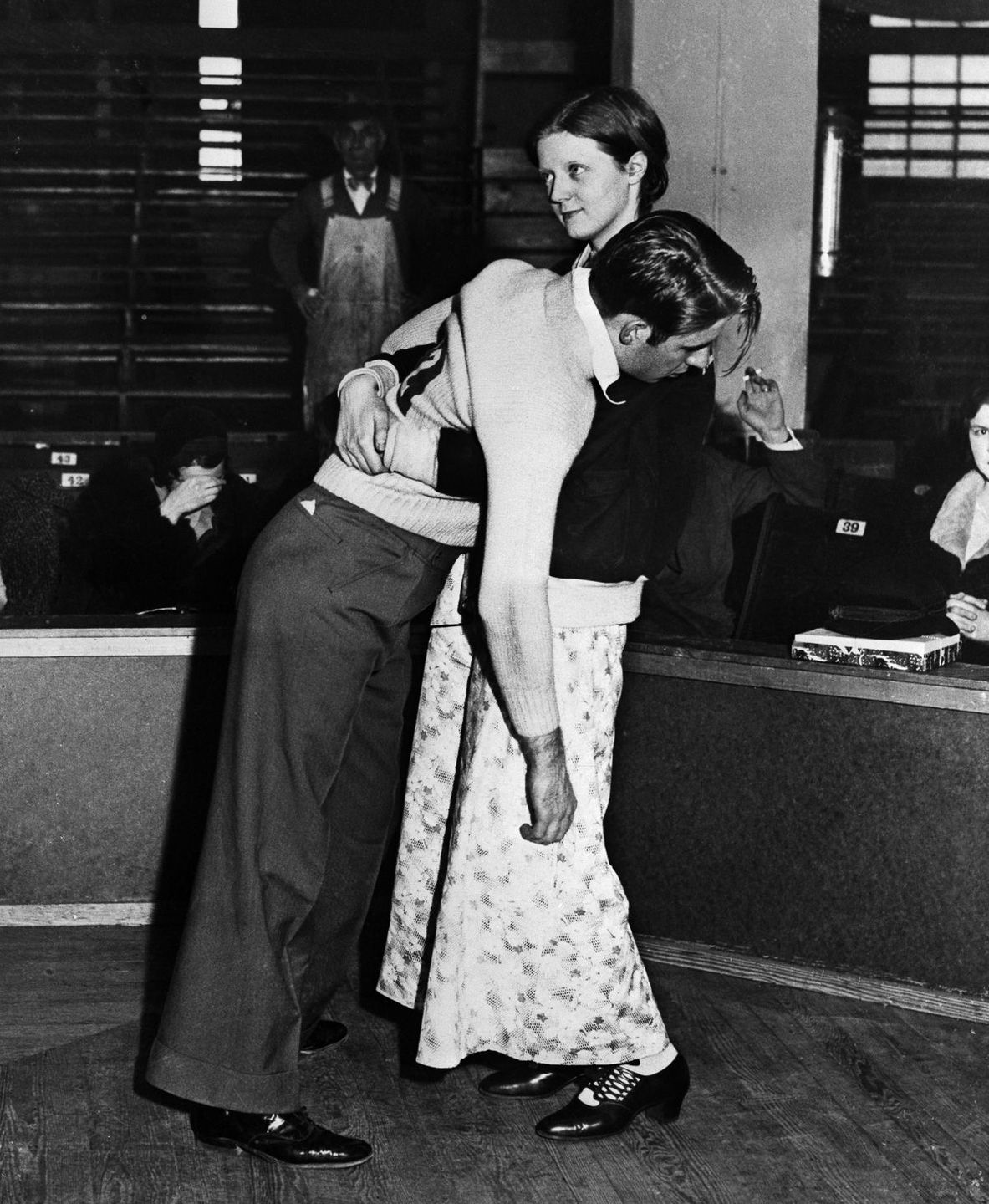

Women often carried their male partners though they may have been much larger than them.

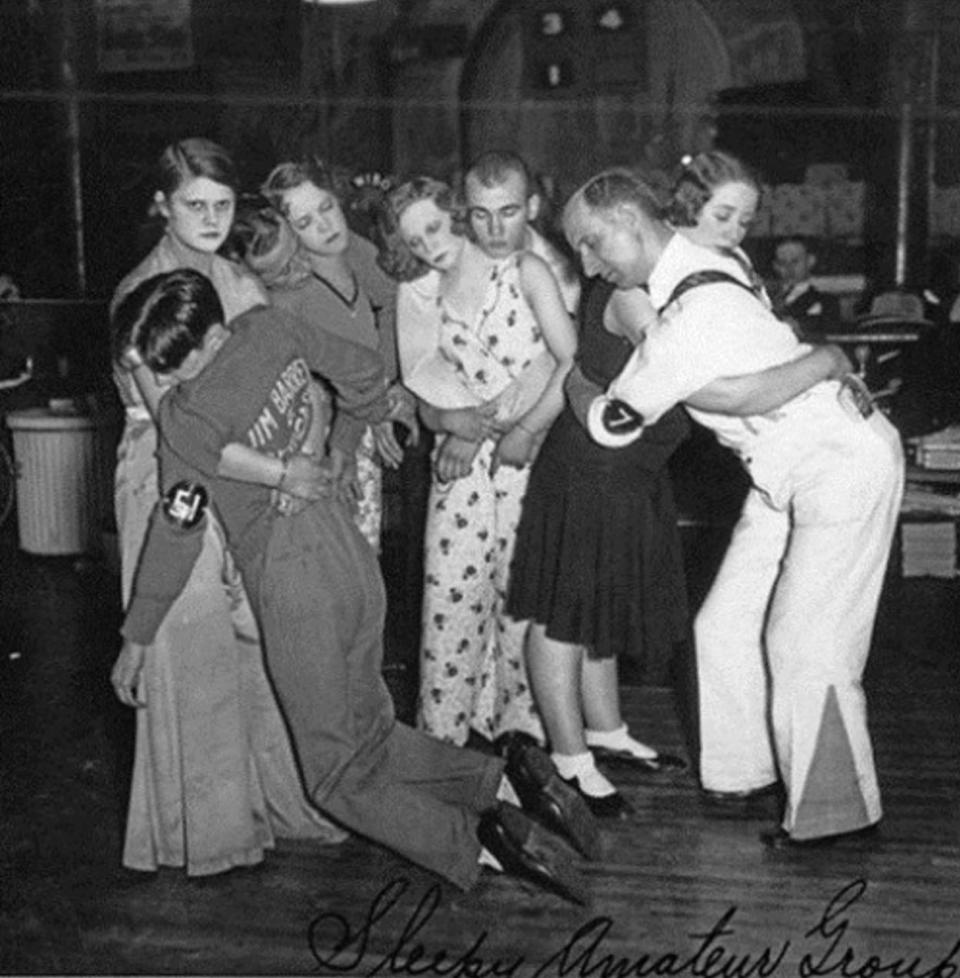

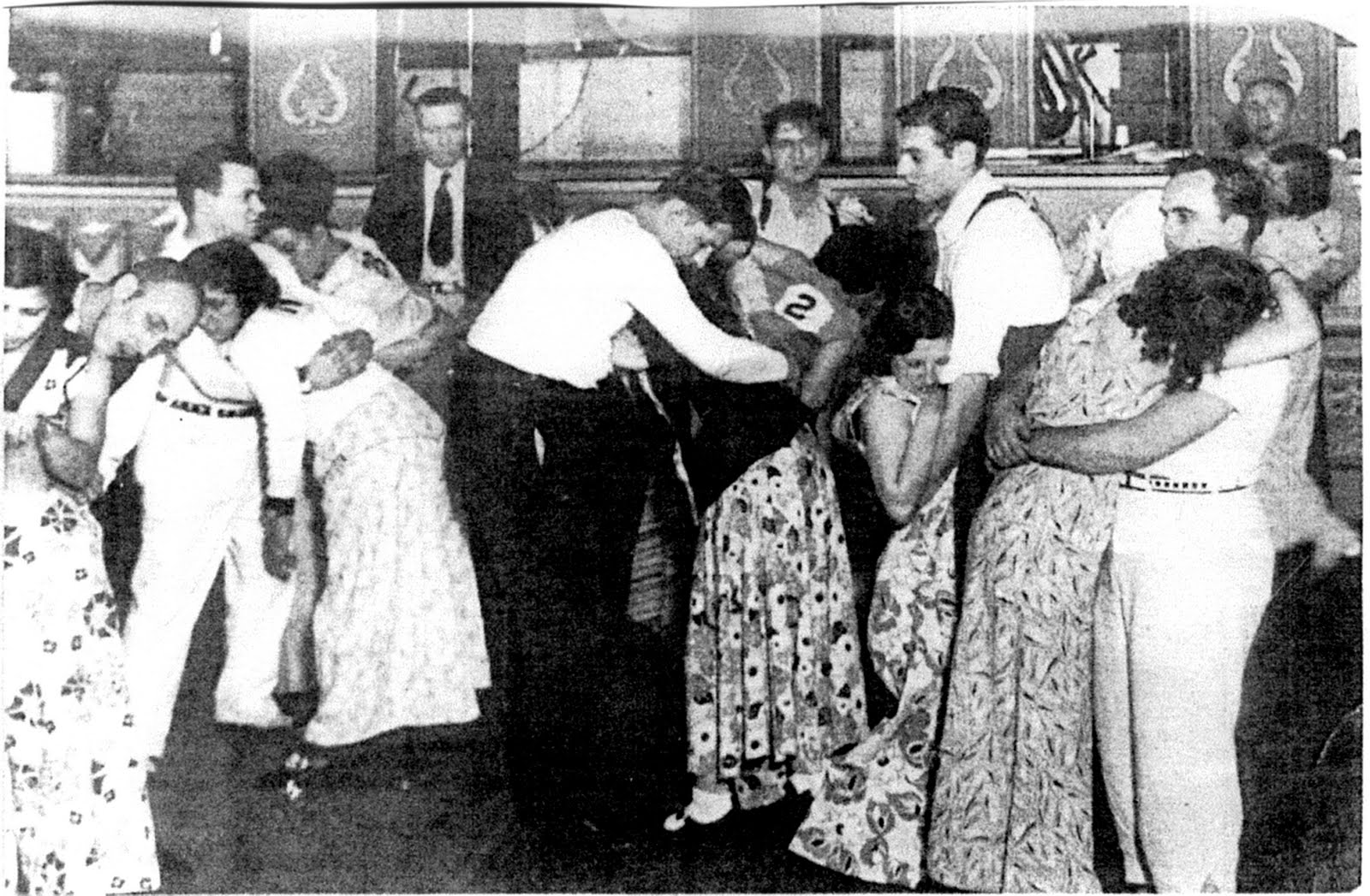

As long as the couples kept moving, they stayed in the competition. Falling to your knees could be grounds for disqualification.

This also helped coin the term “walkathons”, since after many hours dancing walking was the most viable option. Since the stigma of dancing in public still prevaded, “walkathon” also sounded less threatening while promoting the event.

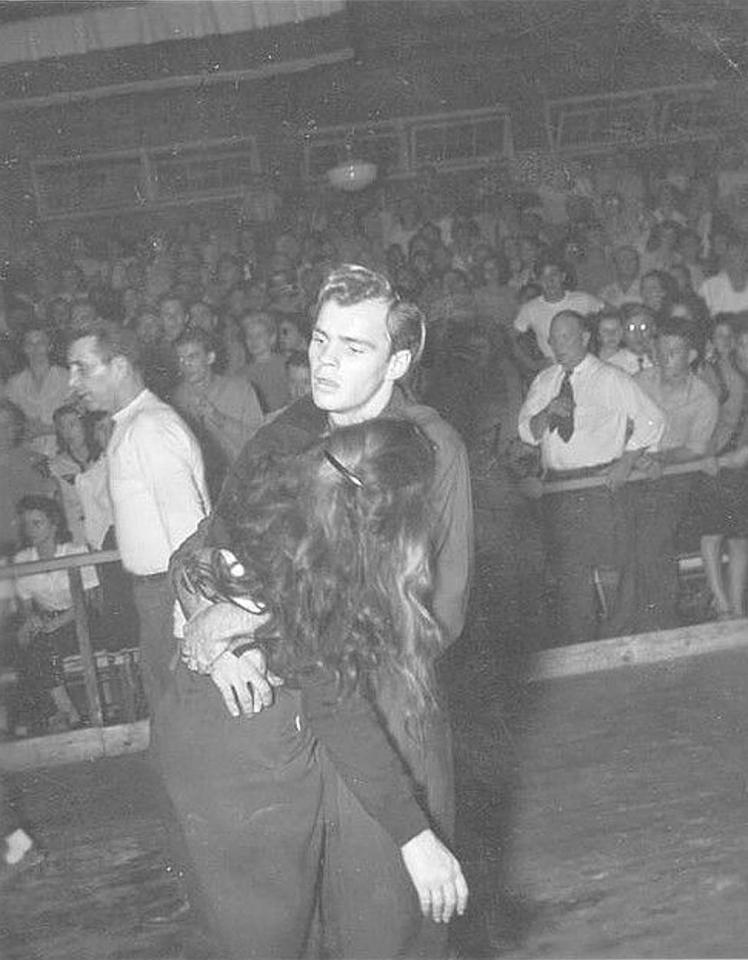

For 45 minutes out of the hour they shuffled their way around the floor, sometimes shaving, writing letters, and performing normal activities like reading, knitting, and even sleeping while their partner supported their weight.

In this video below ↓ from a dance marathon in 1931, start from the 1:08 mark to see a dancer shaving while his dance partner holds the mirror.

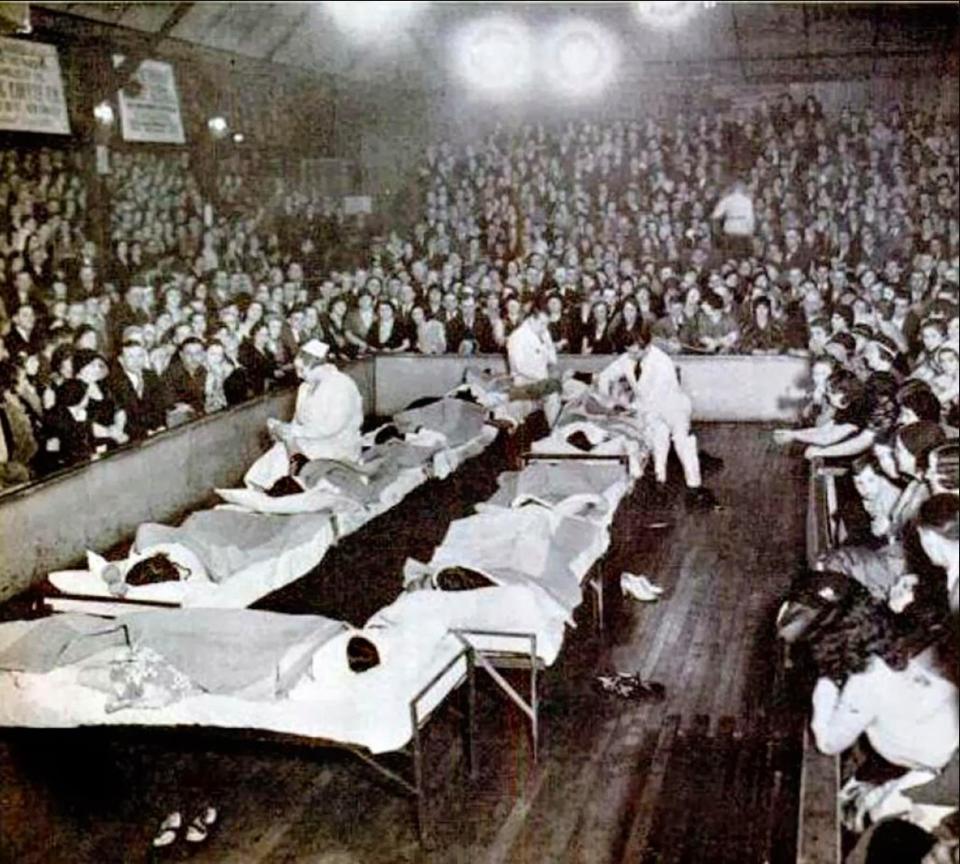

Every hour marathoners were allotted around 15 minutes to rest, sometimes less depending on the event.

Once an airhorn sounded, the couples exited the floor and entered private areas segregated by sex and filled with cots (though sometimes these were brought right onto the floor). There they would plop down and pass out immediately, to be woken up by the airhorn and shuffle back onto the floor. If a female contestant did not wake up they sometimes received smelling salts and slaps, whereas the men were dumped into a tub of ice.

Another part of playing the game was to keep up a strong appearance so that companies would want to sponsor your team, giving you new clothes with their logo on the back.

Though the mundanities of normal life may have been allowed during the off-hours when the phonograph played, at night when the stands were packed and spectators (mostly women) cheered for the favorite couples, they were expected to dance full-out to a live band.

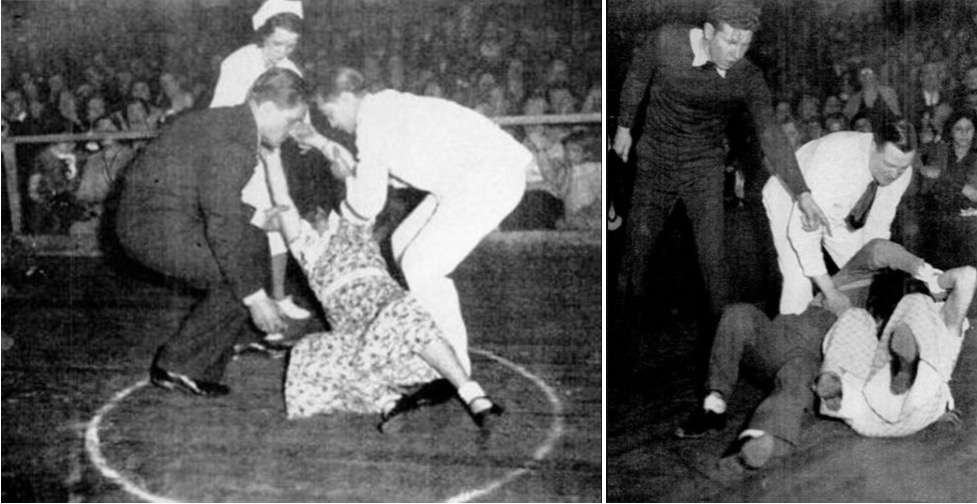

As the marathon dragged longer and attendance increased, the couples found themselves subjected to more grueling tasks in their somnambulistic states. Added events like sprint races (“derbies”), the removal of rest periods, and long periods without medical care caused marathoners to drop like flies (there was a grace period to find a new partner if yours dropped out). Injuries like swollen legs, shin splints, blisters and bunions, and fallen arches were common among them, but the greatest stress of all was overcoming the mental wall of how much exhaustion a human could endure.