In the midst of towering apartments and neon-lit bodegas, you’ll find the Dyckman Farmhouse, Manhattan’s oldest abode and only farmhouse. The white clapboard cottage has been perched on a hilltop on present-day Broadway for 234 years, slipping under the radar of tourists and New Yorkers alike and looking like a bit of a mirage in its otherwise urban surroundings…

The neighbourhood of Inwood, or “Tubby Hook” as it was known back in the day, was founded in the early 17th century by the Dutch. Legend has it that they purchased the entire area from the Lenape tribe for $24 dollars and some glass beads.

The territory was prime farmland, and Westphalian immigrant William Dyckman was amongst the first to arrive in 1661. He immediately snatched up 250 acres of land.

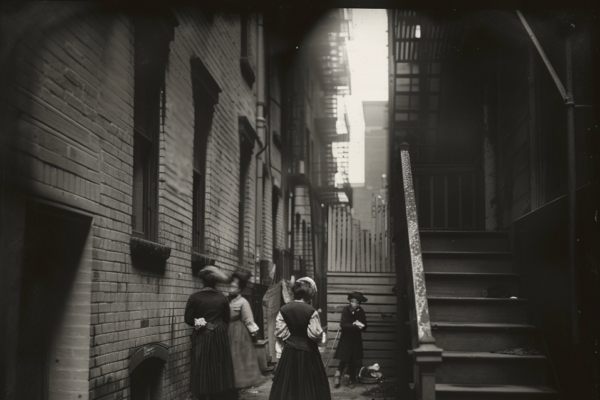

The Dyckman farm, early 1900s.

The area remained rural into the mid-20th century, and today it’s the last Dutch farmhouse in all of Manhattan. Stepping inside the Dyckmans’ old home feels a but like walking with friendly colonial ghosts…

The two-story house is made out of fieldstone, brick, and white painted wood. The gambrel roof is a classic Dutch feature, as are the porches on either side of the house.

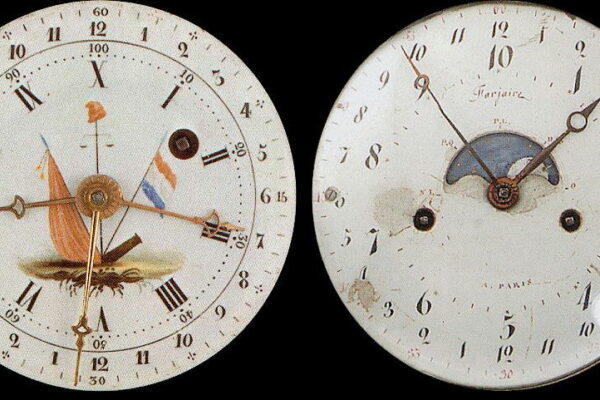

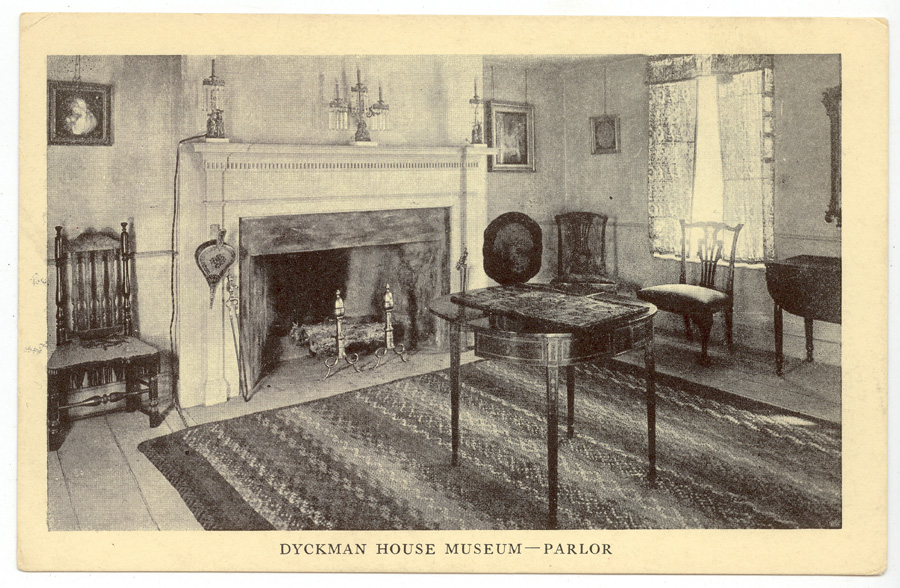

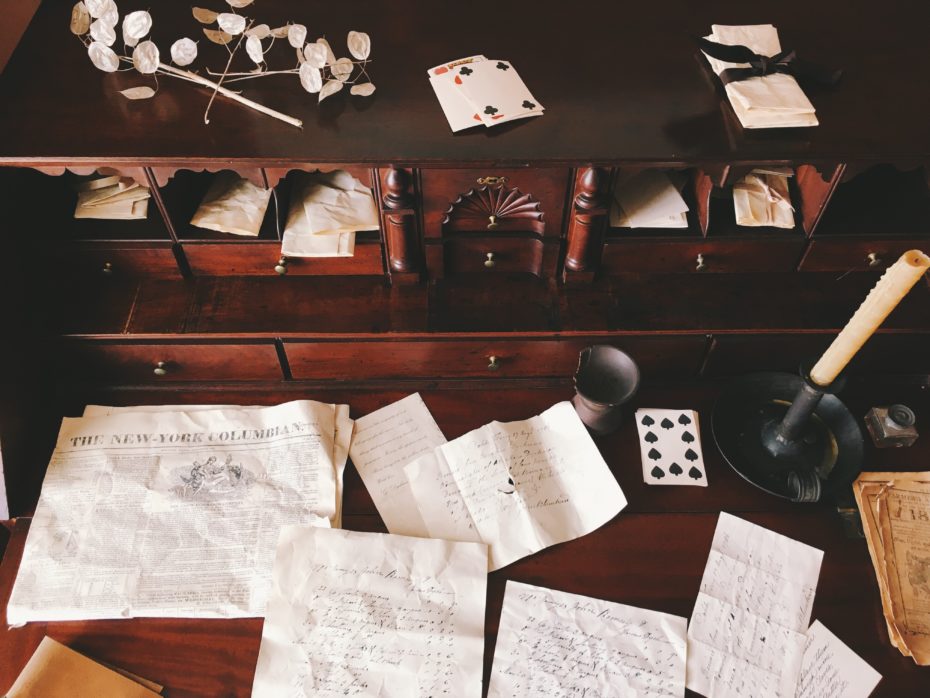

There are two parlours in the house, one of which serves as a kind of front desk for the museum. The other, however, is dotted with the personal archives of the Dyckmans themselves. Everything from half-opened letters to century-old newspapers riddle the desks, and you almost expect to see William or his son, Jacobus, round the corner to light the fireplace. Here’s one of the parlours in the early 20th century:

And today:

At its peak in the early 19th century, the farmhouse could house around a dozen or so family members.

There were stables, a barn, and (thanks especially to Jacobus) a cider mill. Life was far from easy on the farm, and the Dyckmans had an admirable track-record of letting weary travelers recuperate at their home, becoming the unofficial inn of the Inwood area.

There was also a subterranean winter kitchen, which you can still peek at today. (Just watch your head on the way down, the ceiling is incredibly low). The hearty brick fireplace could fit several cauldrons, and aside from heating meals, warmed up the entire home:

Life was hard but simple for the family, at least until the British occupation of Manhattan. At that point, the Dyckmans went into hiding, and to this day historians aren’t certain about how exactly they survived.

The family emerged from the Revolutionary War to find their original home in utter ruin and their orchards burned — but they were a tough bunch. The youngest, William, started rebuilding the home (and what is essentially the present cottage) in 1785. Jacobus took over construction after his father’s death, and their descendants lived in the house until 1868.

Between 1809-1822, Jacobus suffered the loss of his wife, four sons, a grandson, and his daughter. Yet the farmhouse stayed in the family, even if it was used as a rental property. Then two Dickman sisters, Mary Alice and Fannie Fredericka decided to spruce up the joint in 1915, undertaking massive renovations before transferring ownership to the city of New York in 1916.

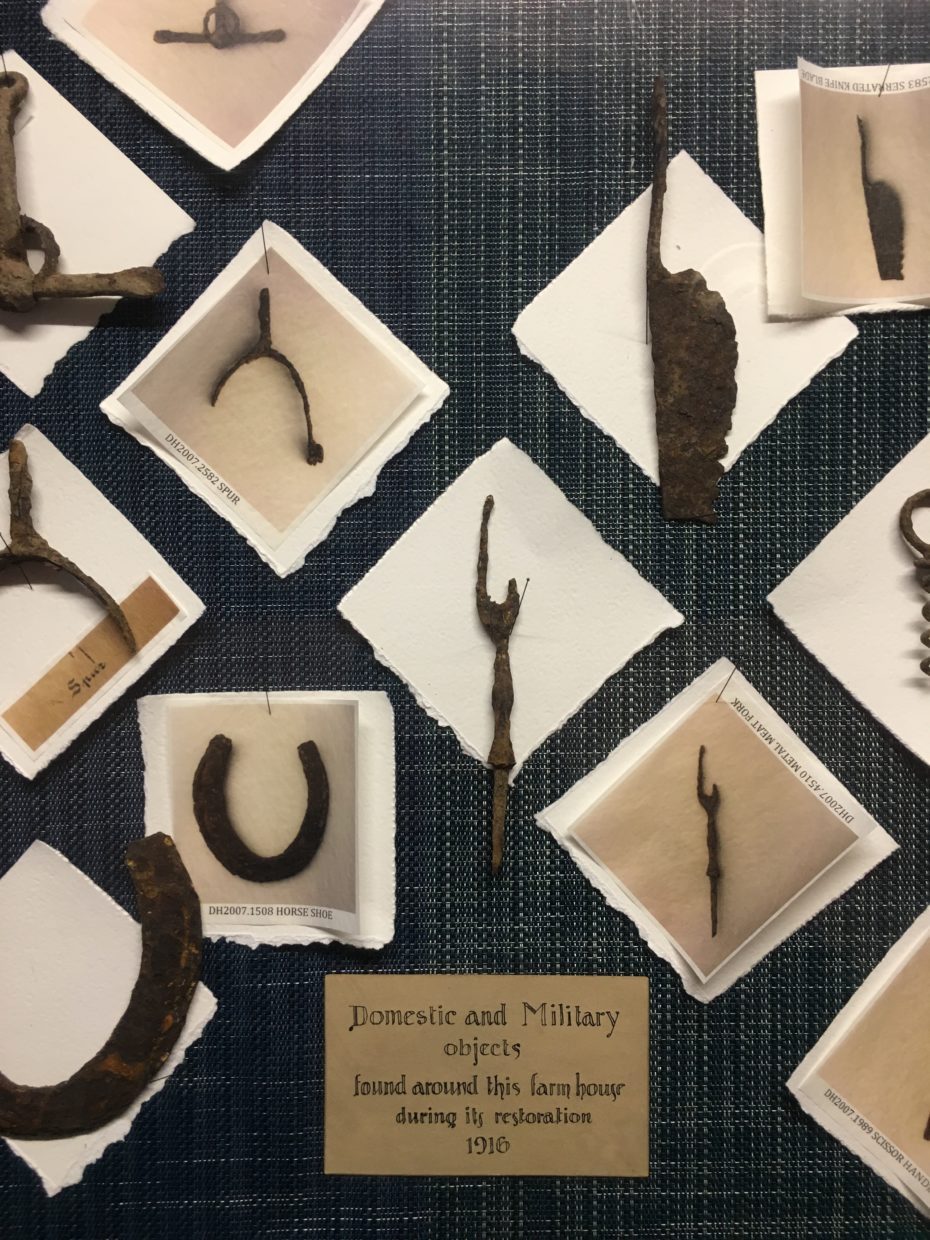

They brought back all of their family’s original furnishings, turning their abode into a museum about Dutch colonialists, and even recruited a group of self-proclaimed “relic hunters” in New York to unearth everything from fossilised pig teeth, pottery, and dice made out of bullets from the yard.

Over 5,000 objects were surveyed, photographed, and documented. They even found an old canon, which is now displayed at the entrance alongside dozens of heirloom planters.

“Everybody knows what the lower end of Manhattan Island looks like,” wrote a 1910 New York Free Press journalist, “thousands of words of poetry have been employed in trying to put on paper its beauty. But probably not one New Yorker in ten thousand knows anything about the extreme northerly end, where trees 400 years old crown Indian shell heaps, and where there still remains a bit of the primeval forest that Hendrik Hudson and his sailors first gazed upon.” Those words still ring true today.

In a city where development never sleeps, and often mercilessly so, the farmhouse is a precious portal into colonial America. “You ask a guy in SoHo about Inwood,” laughs one resident while waiting for a bus, “They probably couldn’t tell you a damn thing about us. But we like it like that here.”

Visiting is free and donation based. Learn more about stopping by the farm here.