In a vast warehouse at the edge of Paris, artisans are working around the clock on a clandestine operation entrusted to them by the Louvre: recreating France’s most iconic sculptures and prints for mysterious clients the world over. And unbeknownst to most of Paris, its doors are open to anyone curious enough to come knocking.

This is “the Louvre’s Sculpture Casting Atelier,” or L’Atelier de moulage de la Réunion des musées nationaux – Grand Palais.

It began two centuries ago in the belly of the Louvre itself, and later moved to the Chaillot Palace by the Eiffel Tower until a devastating fire played a role in relocating the atelier further afield.

Today the team’s works from their Saint-Denis headquarters, a supposed “No Go zone” of Paris, to better accommodate the size of the ever-growing collection.

Since 1793, they’ve been supplying France’s most prestigious Beaux Arts schools and national museums with the replicas of fragile, ancient masterpieces.

At the Palace of Versailles, over half of the statues you see in the palace gardens were in fact born in this Atelier, and swapped with the delicate (and time-worn) originals that now live safely inside in protected archives.

They work with individual clients too– everyone from Jeff Koons to Disney. “I happened upon [the Atelier’s] old location 20 years ago,” a former Disney employee told us. “When I got back home, I showed my photos to the sculptors at Disney (where I was working) and they ended up ordering lots of pieces for the Tokyo Disney Sea Park.”

On any given day, you can find the Winged Victory of Samothrace sharing the same corner as ancient Egyptian sphinxes; the heads of bygone French aristocrats mingle on shelves before finding homes in private estates and institutions.

The atelier even has its own boutique beneath the Pyramid of the Louvre so art lovers can take home a piece of Paris. The online boutique also offers most of the archive’s best-sellers and is certainly worth a browse for an extraordinary souvenir.

“To see a life-sized Moses, Michelangelo’s Pieta, or a parade of Medici sculptures walk out of these doors…it’s extraordinary,” says the man at the helm of it all, Thomas Lefeuvre. He leads us in and out of the workshop’s seemingly endless hallways, and into its passcode-protected vaults.

He gives us a peek at some of the most antiquated prints and maps of Paris, official archives hidden down a dark passageway at the back of the engraving department. We arrive when a young woman has just rolled up her sleeves to unfurl a breathtaking 18th century portrait of the aristocrat Madame de Pompadour.

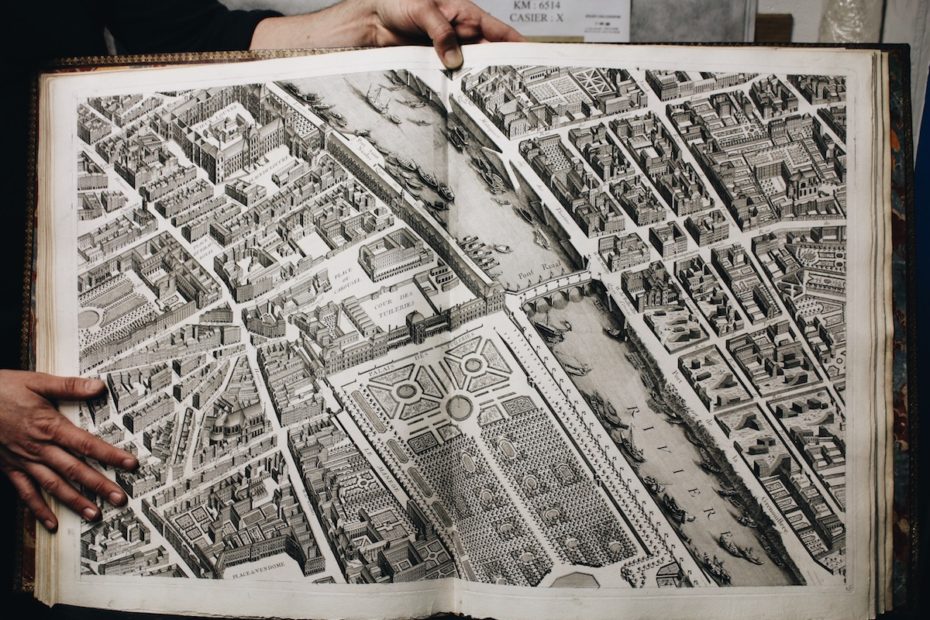

The Louvre itself holds a rare and impressive collection of historical prints tucked away on the upstairs floor of the museum in central Paris, known as La Chalcographie du Louvre. If you make it up there, you’ll find some 13,000 engraved prints, bound in hundreds of enormous leather books to flick through peacefully, away from the crowds. There are maps of pre and post-Haussmannian Paris, Napoleon’s campaigns in Egypt, society scenes from Versailles– it’s an endless library of France’s most beautiful graven works. And the best part? Every single one of them can be yours at your request—which of course, will be sent here, where a master printer will make them for you in this very workshop.

Every last original copper plate used to engraven the historic prints is safely guarded here in a windowless passcode protected room. Thomas pulls out the copper plate used to make the invitations to an 18th century French Prince’s wedding.

He lets us run our fingers over the precious etchings of a scene depicting Molière’s play at Versailles being performed in front of the sun king. We could have it made on the spot if we wanted. Lucie, one of the highly-trained artisans downstairs could run it off through one of the antique pressing machines for a minor investment.

We enquire about the 18th century detailed map of Paris, which goes for 150 euros, or if we’d like the 16 foot-high version, it will set us back 3000 euros.

“Above all, the Atelier is concerned with education. The preservation of these sculptures’ artistry,” says Thomas with a tremendous foot in-between his hands, “Rodin studied them tirelessly. Delacroix never went to Italy, but these moulds brought Italy to him.”

There’s a small Statue of Liberty perched on a windowsill— she was designed and born on French soil, after all — and a spliced Winged Victory beside a woman’s workspace. There are the doors of Notre Dame, and the footprints of a Joan of Arc sculpture.

“It’s true that the two world wars, and especially the first, were huge blows to French Patrimony.” Thomas gives the example of “The Smiling Angel” of the city of Reims, who was nearly lost to the bombardments of WWI. “The face of that angel was, and remains, one of the greatest symbols of gothic art. And of France, really. The only way we could piece her back together was with help from our moulds.”

That implication of safeguarding France’s treasures is the thread running throughout this operation. In the event that the original sculptures are lost or destroyed, as they so often are by war, revolution, or natural disaster, your realise that the Atelier’s moulds are the key to preserving their legacy. This is the only back-up plan.

Today, Thomas dreams of bringing Michelangelo’s David to life. “It would be quite a feat,” he tells us, “there’s already a very high demand for him.”