Without Neta Snook, there may never have been an Amelia Earhart. “The Lone Aviatrix” of Iowa had been shattering the proverbial glass ceiling with her plane long before the Earhart took to the skies, and she did it in a plane she assembled in her parents’ backyard. In other words, Snook was the kind of woman who saw what she wanted, and didn’t just ask for it — she built it with her own two hands.

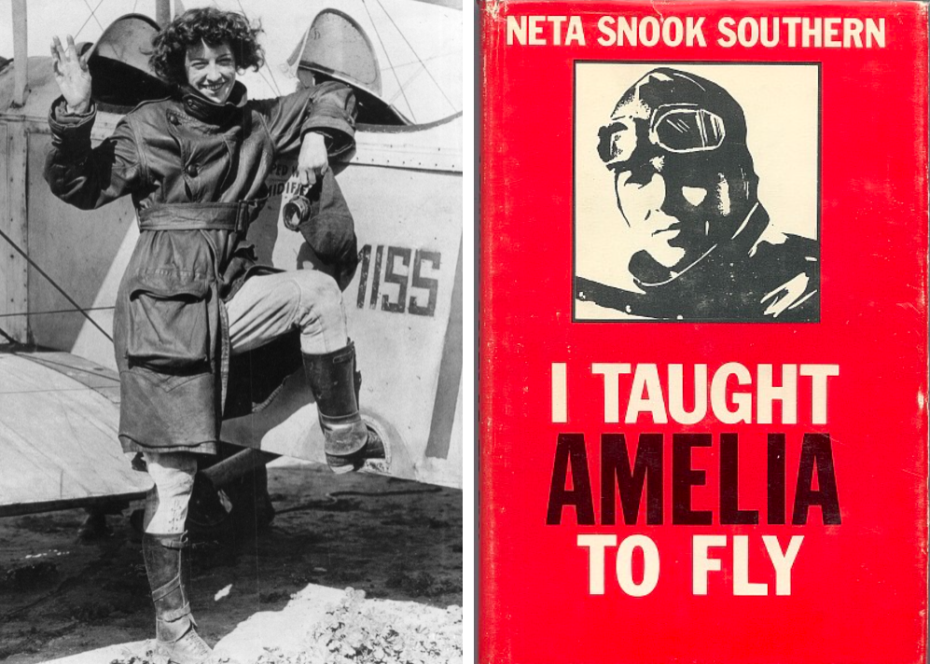

She was one of the first female aviators in the Midwest, and the first female student accepted into the prestigious Curtiss Flying School. She was even the first woman to operate a commercial flying business. But above all, history’s bookmarked her as “the woman who taught Amelia to fly.”

According to her mother, she was slated for speed from the get-go. “When she was little, Neta made toy automobiles that would run and boats that would sail in preference to playing with dolls.” By nine, she was tinkering with her dad’s car.

Yet, for every ‘first’ ticked off her list, she faced twice the rejection. The Curtiss Flying School initially responded to her application with a blunt “no females allowed.” The tragic death of her first aviation school’s president in a plane under her supervision forced the entire program to shut down. Then there was the ever curious herd of her traditional neighbours, who looked on with raised brows as she resurrected a Canuck plane in her parents’ backyard.

“People came to see it and asked, ‘How will you get it out of this small yard? Can you fly straight up? Which is the front end?,’” she wrote, “There were few people in the middle west who had ever seen a plane.”

She became a kind of local sky taxi, offering 15 minute spins in her plane for $15, and entered as the only woman against 40 men at the LA Speedway flight competition in 1921, and came in fifth. “I have to fly for the whole sex, as it were, and I’m going to show the world that a woman can fly as cleverly, as audaciously, as thrillingly as any man aviator in the world.” She finished in fifth place.

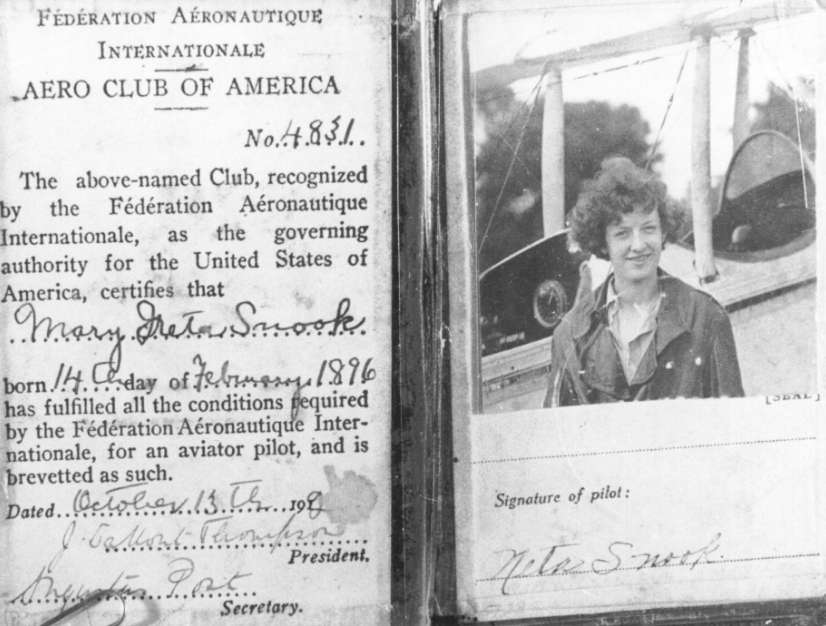

And while her U.S. license was a feat, it was her recognition from La Fédération Aéronatique Internationale, that gave her international validation. “That was the climax of my aviation career,” she wrote, “I was a recognized pilot all over the world.”

Enter a starry-eyed Earhart in December of 1920. “I’ll never forget the day she and her father came to the field,” recalled Snook, “I liked the way she stated her objective. ‘I want to fly. Will you teach me?’”

Earhart had seen her idol in action years earlier at the State Fair in Des Moines, and apparently the magic stuck. The ten minutes they spent in the sky that day convinced her, she would later say, to pursue the skies. The two remained close friends and aviation comrades up until Earhart’s disappearance.

What resonates most about Snook’s primary claim to fame with Earhart (she did call her autobiography, I Taught Amelia to Fly) is the way in which it unfolded: as an empowering mentorship, from woman to woman, that shook up an otherwise all boys’ club. And as for Snook, the aviatrix was active until her death at 95.

(Seriously, here she is with a pony chariot in later years):

Neta Snook, ladies and gentlemen: our wing girl of the day.