The possible survival and escape of the Grand Duchess Anastasia of Russia, was one of most captivating and romantic mysteries of the 20th century. The youngest daughter of the last Tsar of Russia, was assumed to have been tragically murdered along with her parents and siblings by communist revolutionaries in 1918, when they were lured by their captors into the basement of their own home, and executed by firing squad.

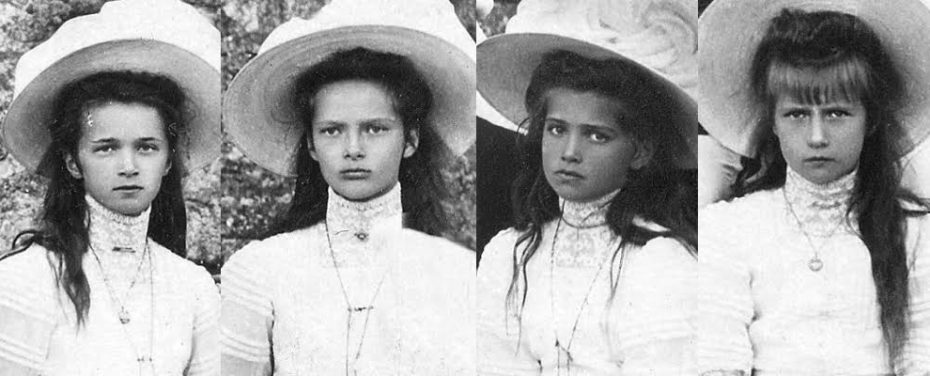

The Duchess, pictured far left as a child, with her sisters and father, Tsar Nicolas II, would have been seventeen years old at the time of the assassination. In the decades that followed, at least ten women came forward claiming to be Anastasia, offering varying stories as to how she survived the Romanov slaughter.

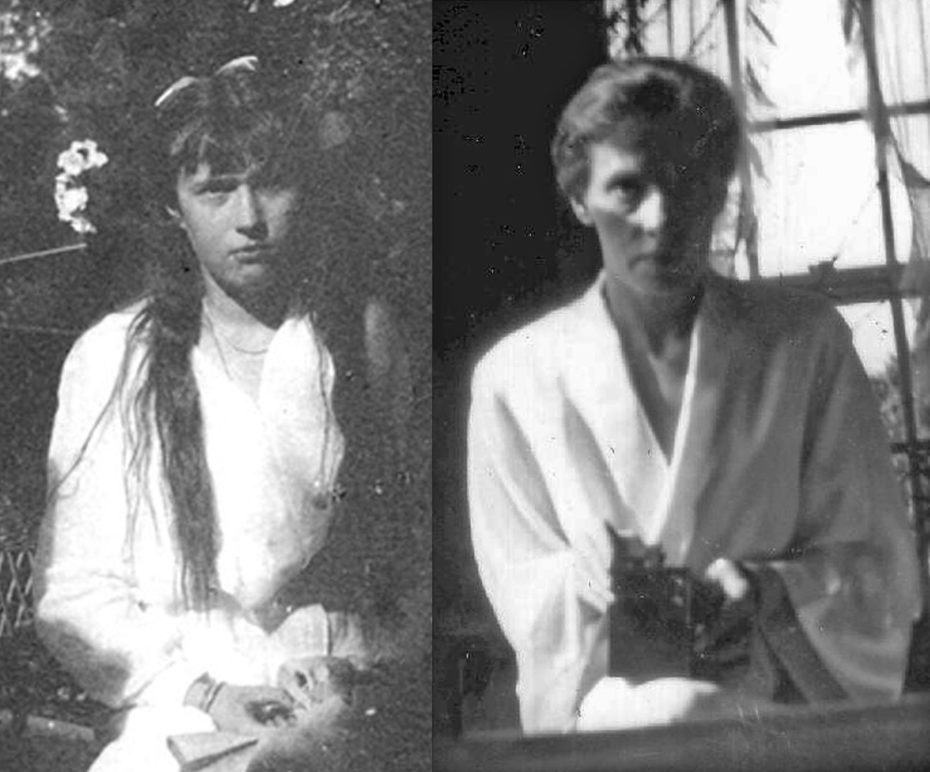

The most famous and convincing of those women was Anna Anderson, who surfaced publicly between 1920 and 1922 after being admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Berlin, initially refusing to identify herself.

A fellow patient first claimed that Anderson, who had been rescued following a suicide attempt, was Grand Duchess Tatiana of Russia, the second eldest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II. A former Russian captain came to visit the unknown woman and intrigued, he began persuading other Russian émigrés to visit the mystery patient, who spoke German with an accent described as “Russian”. Eventually, Baroness Sophie Buxhoeveden, a former lady-in-waiting to the Tsar’s wife, Tsarina Alexandra Feodorovna, visited the asylum.

Upon seeing Anderson, she declared, “She’s too short for Tatiana,” and left convinced the woman was not a Russian grand duchess. A few days later, the nameless woman noted, “I did not say I was Tatiana.” She began opening up to the nurses of the asylum, confessing that she was in fact another daughter of the Tsar– Anastasia. She explained how she had hidden among the bodies of her family and servants, and was able to make her escape with the help of a compassionate communist guard who noticed she was still breathing and took sympathy upon her.

Her claims would later result in the longest running legal case ever heard by the German courts. Most members of Grand Duchess Anastasia’s family and those who had known her, believed Anderson was an impostor but others were convinced she was the real Anastasia.

Some of her earliest and key supporters were Tatiana and Gleb Botkin, children of the imperial family’s personal physician, who had been murdered by the communists alongside the Tsar’s family in 1918. They had known Anastasia as a child and Tatiana had last spoken with the Duchess in February 1917.

She saw a striking resemblance in the woman claiming to be Anastasia and decided that her inability to remember events and refusal to speak Russian was a result of her trauma. To help the woman’s weak memory, she began coaching Anderson with insider details of life within the imperial family.

It was around this time that she began calling herself Anna Tschaikovsky, choosing “Anna” as a short form of “Anastasia”. She began living off the finances of those who believed she was indeed the lost Duchess, which included some members of the Imperial family. The woman who’d been plucked from a mental asylum in Germany was suddenly living amongst Europe’s wealthiest aristocracy, being passed from one wealthy benefactor to another.

After living at the expense of Grand Duchess Anastasia’s great-uncle for a spell, she found herself at Castle Seeon, hosted by a Duke and distant relative of the Tsar. Meanwhile, more suspicious members of the Imperial family hired a private detective to investigate Anna’s story.

The detective returned with a report, claiming that Anna Tschaikovsky was in fact a Polish factory worker called Franziska Schanzkowska, who’d worked in an arms factory during World War I. During one of her shifts, a grenade had fallen out of her hand and exploded, causing injuries to her head and a fellow co-worker’s death. Already a widow of war, Schanzkowska had become severely depressed and declared insane.

The son of the Duke who was hosting the alleged “lost Duchess” at Castle Seeon, was hell-bent on proving that she was an imposter. He tracked down the brother of the Polish factory worker, and organised a surprise meeting between Felix Schanzkowski and their dubious guest, hoping to witness the moment of sibling recognition. Years after he was called to a local inn near the castle to meet the woman claiming to be Anastasia, Felix’s family said that “he knew Tschaikovsky was his sister, but he had chosen to leave her to her new life, which was far more comfortable than any alternative”.

Despite numerous princes, princesses and relatives of the Tsar labelling Anna, “an adventuress, a sick hysteric and a frightful playactress”, one going as far as to say, “I am convinced that you would recoil in horror at the thought that this frightful creature could be a daughter of our Tsar,” just asmany credible friends and relatives were convinced that Anna Tschaikovsky was genuine, or at least, wanted to believe she was.

In the late 1920s, her story broke America, feeding the fairytale to young working-class women across the country, dreaming of a better life. Published articles quickly reached Xenia Leeds, a former Russian princess and distant cousin of Duchess Anastasia married to an American industrialist, who arranged for Anna to travel to the United States. On her way, Tschaikovsky stopped in Paris, where she met the Tsar’s exiled cousin, Grand Duke Andrei Vladimirovich of Russia, who also believed her to be the true Anastasia.

Anna settled in New York and lived for 6 months on the Leeds estate, before being kicked out over some rumoured disputes about Tschaikovsky’s claim to the Romanov estate. She lived in hotels for a while, checking in under the new name “Anna Anderson”, to avoid the press. Going by her new moniker, Miss Anderson was then taken under the wing of a wealthy Park Avenue spinster, Mrs Jennings, who was all too happy to host the alleged daughter of the Tsar, particularly as she became the toast of the town and society’s favourite party piece.

But Anna Anderson, Duchess or not, was still a damaged soul, and a pattern of self-destructive behaviour soon began her downward spiral. She repeatedly threw violent public tantrums, killed her own pet parakeet and ran naked on the rooftops before she was forcibly taken away to a mental hospital and sent back to Germany a year later on Jenning’s dime.

At the end of World War II, a German prince helped her escape the Soviet occupied zone and cross safely into occupied France where she stayed in some army barracks and became a tourist attraction of sorts. Friends of the Tsars continued to visit her, some acknowledging her as Anastasia, others denouncing her, including the English tutor to the imperial children, who declared, “she in no way resembles the true Grand Duchess Anastasia that I had known … I am quite satisfied that she is an impostor.”

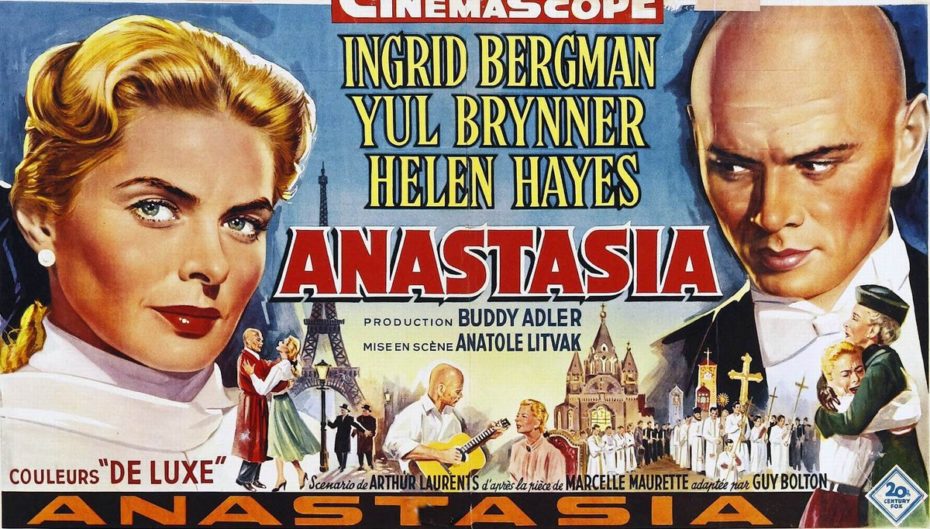

In the 1950s, she settled in a small village in the Black Forest of Germany, and became a recluse and a hoarder, living in a dilapidated cottage with 60 cats. By this time, countless works had been inspired by her claim to be Anastasia and in 1956, actress Ingrid Bergman won an Academy Award for her starring role in the 1956 film Anastasia, inspired by Anderson’s claim.

In 1968, her earliest and long-term supporter, Gleb Botkin came to her rescue, offering to move her back to the United States. It was there that she met Jack Manahan, a wealthy history professor known as “Charlottesville’s best-loved eccentric”. They were married shortly before the expiration of her visa. Despite his wealth, they lived as hoarders together in squalor and she was once again institutionalised in 1983.

Never one to make a dull exit, she broke her out of the asylum and drove around Virginia with Jack for days until a 13-state police alarm saw her returned to the facility, where she died of pneumonia in 1984. Her ashes were buried in the churchyard at Castle Seeon.

DNA tests were carried out a decade later on a sample of Anderson’s tissue and the blood of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (the very same husband to the current Queen of England), who is also a second cousin of Duchess Anastasia. According to the doctors who conducted the tests, “If you accept that these samples came from Anna Anderson, then Anna Anderson could not be related to Tsar Nicholas or Tsarina Alexandra.” On the contrary, her DNA did match with a great-nephew of Franziska Schanzkowska, the missing Polish factory worker.

The location of the body of the true Grand Duchess Anastasia was unknown until 2007. In 1991, the bodies of Tsar Nicholas II, Tsarina Alexandra, and three of their daughters were exhumed from a mass grave near Yekaterinburg, identified through skeletal analysis and DNA testing. More than a decade later, the skeletal remains of Tsarevich Alexei, the youngest sibling (and heir to the throne of the Russian Empire), was discovered at a bonfire site near Yekaterinburg alongside that of his sister’s, Anastasia. Repeated DNA tests confirmed that none of the Tsar’s four daughters survived the tragic shooting of the Romanov family.

Cunning imposter? Traumatized into adopting a new identity? Or used by her supporters for their own ends? Whichever is the truth behind Anna Anderson’s intentions, it seems to me that her story provided some much needed hope for one of history’s most tragic tales.

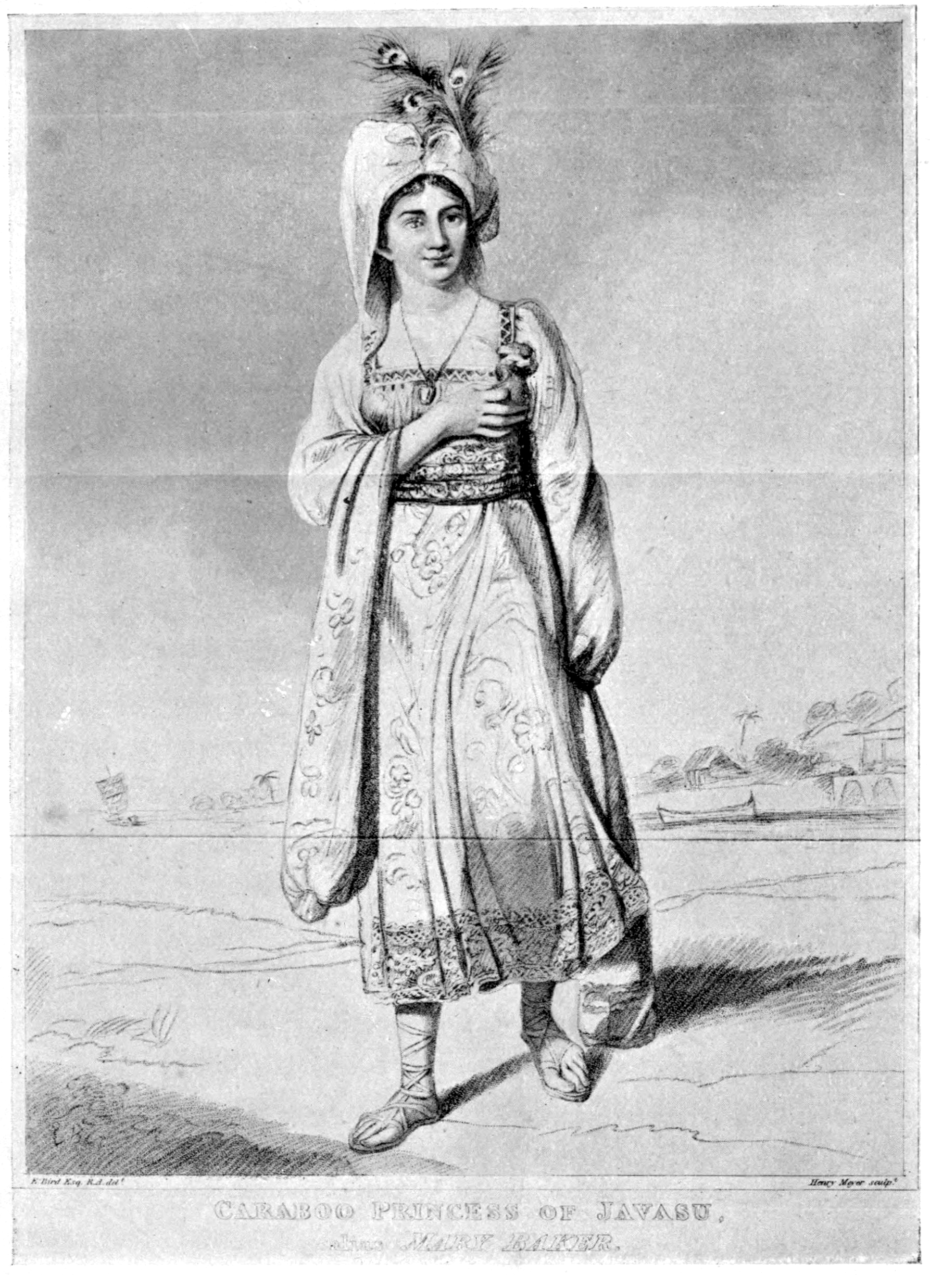

And as strange and far-fetched as her story seems, Anderson was not the only Princess imposter. Meet, Mary Baker, aka, the Princess of Caraboo. In the early 19th century, she fooled a nation, sensationally convincing them that she was a fictional princess from a far off kingdom.

In 1817, a young woman wearing a black turban stumbled into a Gloucestershire village, carrying her possessions in a bundle, exhausted and near starving. The town’s cobbler and his American-born wife, the Worralls, took her in. She was speaking a language foreign to anyone in the village, and when she saw a painting of a pineapple, she excitedly pointed at it, repeating the word ‘nanas‘, the Indonesian translation for the what was then considered an exotic fruit, afforded only by royalty. The mysterious and beautiful woman exhibited strange behaviour and insisted on sleeping on the floor. She was briefly arrested for vagrancy, where she met a Portuguese sailor who claimed to speak her language and translated her story.

She claimed to be Princess Caraboo from the island of Javasu in the Indian Ocean, captured by pirates after a long voyage. She had arrived in England by jumping overboard in the Bristol Channel, and then swam ashore. After she was released from prison, the alleged Princess became a local celebrity, welcomed as exotic royalty by the dignitaries of Gloucestershire, and her bohemian ways provided much entertainment for the English countryside. Once she had convinced them that she couldn’t speak or understand English, they felt free to speak in front of her, providing her with the tools she needed to continue her deception. She could often be spotted using a bow and arrow, fencing with the aristocracy, swimming naked or praying to a god she called Allah-Talla (a spelling variation of one of the formal names for God in Islam).

She had her portrait painted and her adventures printed in newspapers, spreading the tale of the Princess of Caraboo nationwide. But when a board-house keeper in Bristol spotted the Princess’s picture in the local paper some months later, the embarrassing truth surfaced. The princess from Javasu was in fact a cobbler’s daughter from Witheridge, Devon, named Mary. She had been a servant girl around England but had found no place to stay. A servant girl with European looks, who found herself homeless, she’d invented her exotic persona and created her own language from imaginary and gypsy words. The British press cruelly ridiculed the rustic middle-class couple who’d first fallen for her story, but Mrs. Worrall, who had always been taken with the girl, took pity on her and arranged for her to start fresh in America.

Even after her story was outed however, a letter was published in the papers, allegedly from Sir Hudson Lowe, the official in charge of a certain exiled Emperor Napoleon, defending and backing up the Princess’ story. He even claimed that after escaping the pirates, she’d rowed ashore St. Helena, where Napoleon was being held and so fascinated the emperor that he was applying to the Pope for a dispensation to marry her.

After a sting in American, peddling her ‘Princess Caraboo’ act on stage, and again back in England on New Bond Street, with little success, she ended up selling leeches to hospitals in Bristol and died a widow at the age of 72 at the turn of the century.

Like Anna Anderson, Mary Baker’s story inspired several novels and screen adaptations. Again, I feel that labelling her a mere imposter does this woman great injustice, who managed to use her own unique talents to break out of society’s cage and rise above the circumstances of her position.

But if two pretend princesses weren’t enough, we’ll finish with a third: the young maidservant who took a role of nonexistent sister of Queen Charlotte…

In 1771, Sarah Wilson was working in the Queen’s House when she began stealing jewellery and clothing from the royal household. She was caught red-handed and sentenced to death, but narrowly avoided capital punishment with a softer sentence. She was shipped off to the colonies, and sold into indentured servitude, but didn’t last long before making her escape. According to the tale, somehow she still had some of the queen’s dresses with her, and began parading around the colonies as “Princess Susanna Caroline Matilda of Mecklenburg-Strelitz”, sister of Queen Charlotte. Wilson’s story was that she’d been exiled to America by her family following a scandal, and she managed to fool a number of wealthy Virginians with her knowledge of royal affairs. One problem: Queen Charlotte didn’t have a sister. It didn’t help that the Queen was originally from Germany and this princess didn’t speak a word of it. The rumours eventually reached her master from who’d she’d escaped and it didn’t take long for him to put two and two together before “Princess Susanna” was being dragged back to servitude. She worked for two years before running off again, this time with a dragoon officer during the War of Independence. Little is known of Sarah Wilson after that, but something tells me she continued to act like the princess she’d always wanted to be.

When I began reading about the stories of our Princess pretenders, I wasn’t expecting to be inspired by them; to find their stories as impressive and adventurous as some of our favourite female pioneers and explorers. While history has them written down as fraudsters, I would argue first that they were dreamers; intrepid, intelligent and imaginative women ahead of their time, who tried to beat the cards that life had dealt them. And can you really blame them for wanting the fairytale? What’s that saying? “Fake it ’til you make it”.