The Golden Ticket worth every penny…

Imagine without hesitating, you could fly to Paris, just to catch the latest exhibition at the Grand Palais, pick up a friend who needed a lift from Milan, maybe swing by the Greek Islands for dinner and be back home the next morning in time for breakfast.

In 1981, American Airlines introduced a membership involving lifetime unlimited first class travel starting at $250,000. Let’s just reiterate that: lifetime and unlimited. Members were given lifelong access to the Admirals Club and American’s VIP lounges and gained air miles every time they flew. The all-important companion pass was on offer for an extra $150,000. Sounds like a pretty good investment doesn’t it? Almost stupid good…

Patrons of the AAirpass were VIPs in the air. Stewards memorized their names, what they liked to eat and in what order.

AAirpass holder Pierre Vroom who racked up over 40 million flyer miles with the airline remembers one flight attendant who would bring him “three salmon appetizers, no dessert and a glass of champagne, right after takeoff. I didn’t even have to ask.”

Another member flew return from Chicago to London 16 times in just 25 days. He bought his AAirpass in 1994 after winning over $4 million in compensation from a car accident.

With their companion passes, holders of the golden tickets could take their liberties. Some would pluck random strangers out of a crowded airport check-in and offer them a surprise upgrade to first class– seats that would be valued up to $10,000. Others would simply book companion seats for the extra elbow room and comfort. Frequent users like Mr. Lowe and Mr. Rothstein regularly reserved their ghost companion seats under the names ‘Extra Lowe’ and ‘Bag Rothstein’.

“They told me how to do it,” said Mr. Lowe

With the help of AA agents, pass holders could even make multiple reservations for the same journey in case they missed a flight or just wanted to have the option, holding seats on flights they never intended to take.

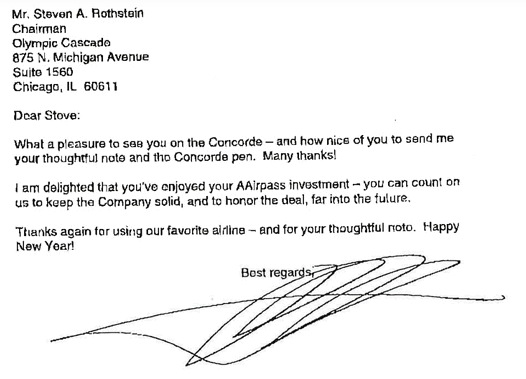

Mr. Rothstein (and Bag Rothstein) made over 3000 reservations over a four year span but cancelled 2/3 of his bookings.

It was this kind of activity that began an investigation into ‘fraudulent behavior’ and landed several AAirpass members at the center of a serious investigation, reported a recent feature in the Los Angeles Times.

Amazingly, the practice of seat-selling had not actually been prohibited for holders until three years after the program was introduced. It was estimated some members were costing the airline up to $1 million in revenue each year.

“It soon became apparent that the public was smarter than we were,” said Bob Crandall, the former AA CEO who resigned in 1998. The airline tried to raise the price of the unlimited AAirpass, first in 1990 to $600,000 and again in 1993 to just over $1 million. AA even resorted to offering some members a full refund in the hopes that they would give up their pass. By 1994 American brought the program to a hault entirely until ten years later in 2004 when they tried to offer it once last time for $3 million ($2 million more for companion passes). They sold a total of zero passes.

All the while, an elite team of investigators had been working behind the scenes to target the members flying the most and losing American Airlines the most money. In a role a little bit like the one played by Tom Hanks’ in Catch Me if You Can (2002), Bridget Cade was in charge of weeding them out.

Under her authority, longtime members were turning up at airport check-in with their guest companions and instead of being given plane tickets, were handed letters informing them that they had been stripped of their AAirpass for fraudulent behavior and were banned from ever flying with the airline again. Humiliated, they were forced to accept that the golden tickets they had purchased 30 years earlier were gone forever and the dream was over.

One bond broker forced into retirement had openly begun using the AAirpass as his sole source of income. By piggybacking a couple from Dallas, Texas back and forth to Europe for $2000 a month, he said, “It’s how I got the bills paid.” Tired of flying, he didn’t kick up a fuss when his pass was revoked, but others didn’t go down without a fight.

Some members sued American Airlines, American Airlines tried to sue members, members countersued etc, etc. It got ugly.

To prove that members were guilty, American resorted to some low-ball tactics, tracking down some of the members’ flight companions. Sam Mulroy, a personal trainer from Dallas who was scheduled to fly as a companion to Pierre Vroom, one of the program’s most frequent fliers, was contacted by an American Airlines agent working for the elite revenue integrity team and told that his flight had been cancelled. If Mr. Mulroy admitted paying Pierre Vroom for his companion seat, the agent would offer him a free first class ticket in exchange.

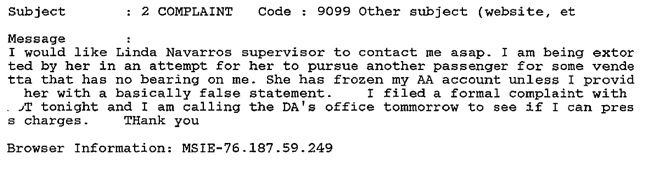

In an email written to American Airlines, Mr. Mulroy complains he was being extorted:

Flight records were pulled and later revealed in court that Pierre Vroom, who often donated his air miles to AIDs victims so they could visit their families, had also been receiving money (up to $100,000) from flying companions (although not necessarily Mr. Mulroy).

Vroom has admitted to receiving money from some flying companions, but his lawyers argue that when he bought his pass in 1981, his contract with AA, which you can browse here, did not prohibit the practice of seat-selling. Vroom also asserts that when he did accept money from flying companions, it was almost always with the understanding that it was for his business advice during the flight. He also claimed a lot of the time his flying companions insisted on paying him some compensation for their seat.

Mr. Rothstein who sued the airline for accusing him of fraud also had his contract from 1987 affirming that making multiple reservations, however suspicious, was not prohibited.

Nonetheless, in 2011, courts ruled that the contracts were in violation. The airline had found their excuse to rid them of their most costly golden ticket holders.

Last November, the American Airlines parent company filed for bankruptcy and the court cases went unresolved.

Steve Rothstein still keeps a courtesy letter from the former American Airlines CEO, Bob Crandall he received in 1998:

So who’s side are you on? The lucky golden ticket holders who took one too many liberties with a dream investment or the major airline company that didn’t quite think it over?

Any original AAirpass holders out there … we’d love to hear your travel stories (and how many air miles you’ve racked up). You know where the comments box is!

Via the Los Angeles Times