Anyone that saw the September Issue will know who Grace Coddington is and probably fell in love with her just like I did. The Vogue Creative Director has penned a memoir, simply titled Grace, and it hits stores this November. In an excerpt published by Vogue online, Grace talks about her early modeling career when she left Wales at 18 years-old for a wild career in fashion.

At a time when top models were being paid just £2 a day for editorial work, Grace takes us down memory lane to 1960s Paris, when Hemingway’s favorite art deco brasseries were still in full swing and regulars like David Bailey and Jean Shrimpton were wooing the French fashion scene.

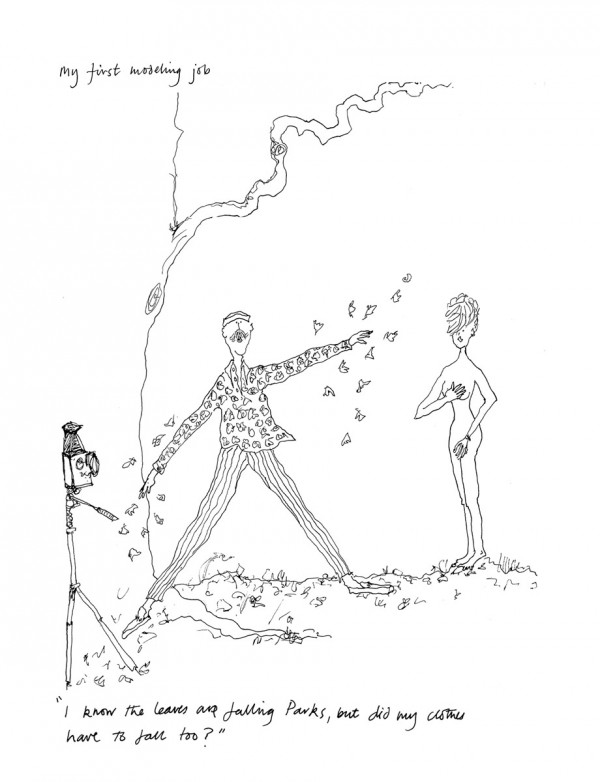

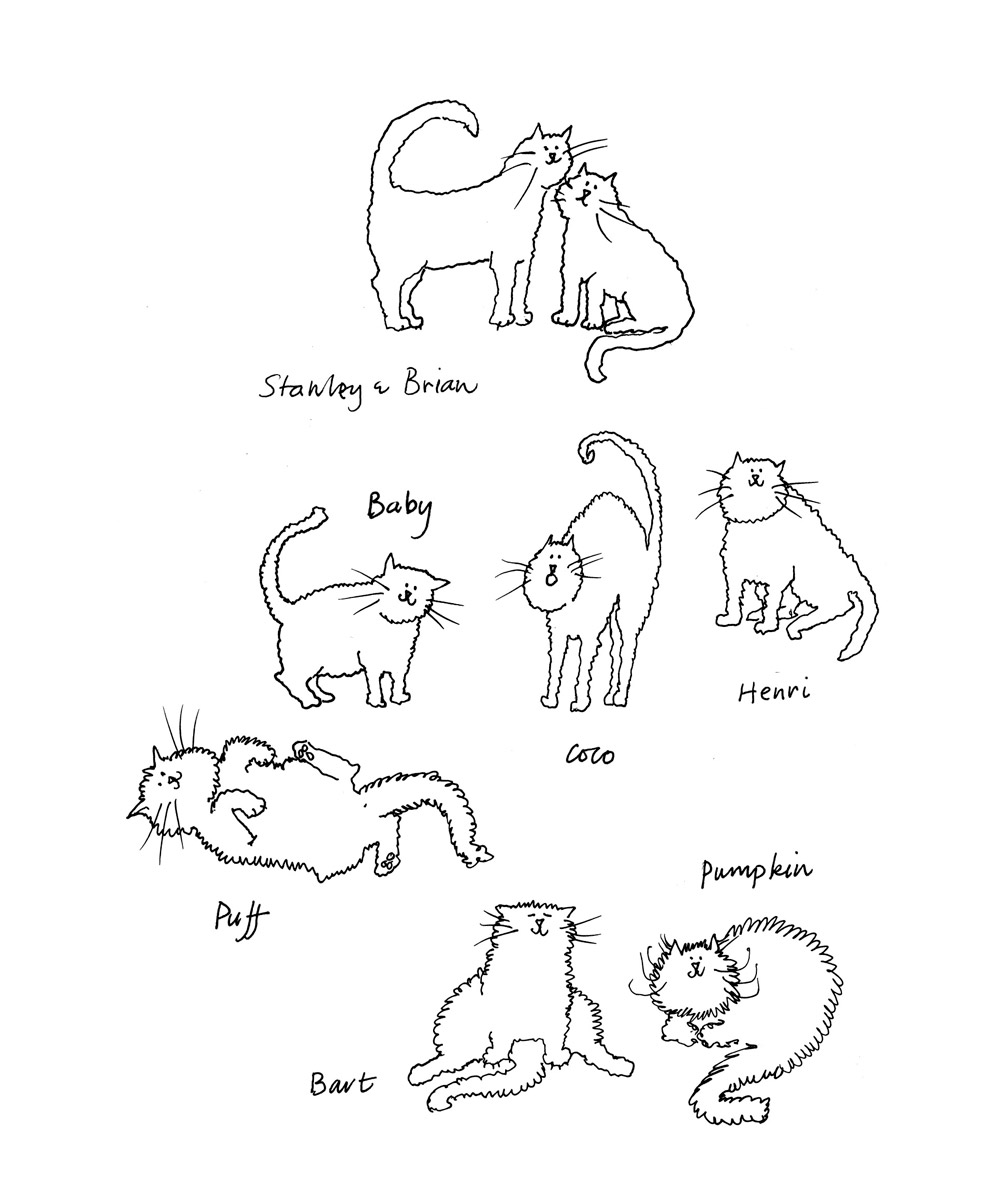

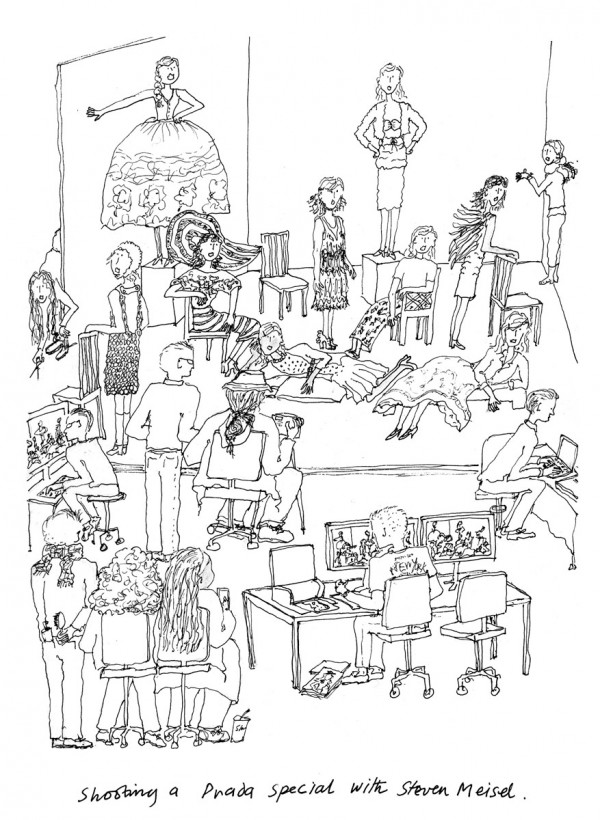

Grace Coddington’s humorous, it’s-cool-to-draw-like-a-12-year-old illustrations are also showcased throughout the memoir.

Grace Coddington’s Paris, from “Grace”, published by Random House:

At the height of the sixties I began regularly flying to Paris for work. I had become fairly well known in British modeling circles, always included on Top Ten lists—but inevitably creeping in at number nine because I was considered avant-garde and fashionable rather than pretty. Since I was a new girl in town, my French agency sent me off on endless go-sees, where I was frequently pushed to the end of a long line of chattering and snooty French models, most of whom wouldn’t give me the time of day. And when I did find work—such as at Elle Studios, which employed a number of photographers who could each use you for a couple of hours—the girls would disappear at lunchtime without saying where they were going. I would sit there, cold-shouldered and starving in the dressing room, wondering where they were until they returned, replenished and refreshed. It turned out that Elle Studios had a cafeteria, but they failed to tell me about it. It was a bit like being in one of those blackly humorous Jacques Tati films, so popular at the time, full of social misfortune resulting from snotty French bloody-mindedness.

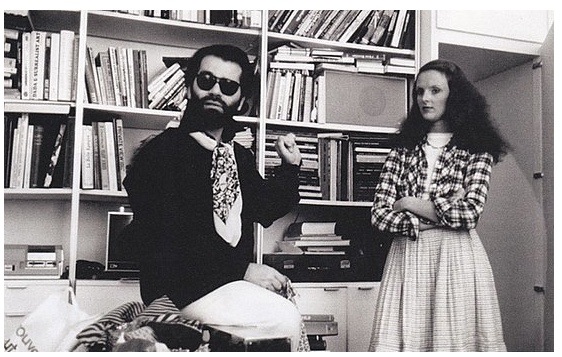

I soon discovered that the Bar des Théâtres in the Avenue Montaigne was the absolute meeting place for career-hungry models and eager photographers. By now I could afford more than “le sandwich.” My budget would even stretch to “le hamburger” and a glass of the new Beaujolais or “vin ordinaire.” Along the way I also managed to acquire a devilishly handsome new boyfriend. Albert Koski was a photographers’ agent with long, dark romantic hair. He was a Polish Jew who dressed beautifully in tailored white Mao-style suits made by Farouche and was often mistaken for Warren Beatty. I found him deeply seductive and quickly became crazy about him. I went to live with him in a beautiful house in Rue Dufrenoy, just off the Avenue Victor Hugo, with a small beautiful garden and a large beautiful cat.

It was a wildly gregarious time for me. Albert and I liked to be seen at the Café Flore in St.-Germain, which was smokily packed with exciting young artists. We ate just across the road from the Flore at bistros like La Coupole, a massive Art Deco brasserie in the middle of Montparnasse that had been open since the 1920s. You could really see Paris in the raw, including shaky old parchment-faced French patrons dotted about the restaurant who obviously hadn’t missed a day of eating there since it first opened. Sometimes, if they were particularly impressed or amused by how you looked or what you wore, they would clap as you passed their tables. The most exotic, exceptional people entering through the swing doors—like the statuesque German model Veruschka and her Italian photographer companion, Franco Rubartelli, or swinging London’s Jean Shrimpton and David Bailey—would garner extra applause. Paris was crawling with models and their relatives, boyfriends, and hangers-on because at that time the fashion scene wasn’t just concentrated around collections time; it was fashion central all year round.

Every night Albert and I could be found dancing (to a twitchy form of early French pop music called yé-yé) until dawn in the fashionable club New Jimmy’s before rushing off to work the next morning. I wore extra-small children’s sweaters in Shetland wool purchased at Scott Adie in London that were all the rage among the French fashion elite, and very, very tight Newman jeans (you had to lie on the floor and energetically wriggle your way into them) that were made of paper-thin cotton velvet or needlecord and came in a huge range of wonderful colors. My penchant for wearing supermodern, very short miniskirts was much tut-tutted by the easily disapproving French, whose fashionable and what they considered far more tasteful “mini-kilts” fell discreetly to the knee.

I was also soon made aware of the way fashion dictates style and how rapidly trends can come and go. Albert had an E-Type Jag that we drove down to St.-Tropez every weekend; or we would put it on the train. We stayed just above the port in a small pension called La Ponche, took our café complet on the narrow balcony outside our room each morning, and rode our VeloSolex (a basic kind of moped) to the most fashionable beaches, either Pampelonne or Club 55 but more often Moorea, owned by Félix, man about St.-Tropez and the proprietor of its chicest restaurant, L’Escale, in the port. We would meet up with friends like the film actress Catherine Deneuve and her new husband, David Bailey; and Ali MacGraw (before she started acting) and her boyfriend, Jordan Kalfus, manager of the well-known American photographer Jerry Schatzberg.

I was astonished by how fashion could change so fast in a few days. You would go to the South of France one weekend and denim was in. The next weekend when you returned, everything was about little English florals. I used to get so worried that I hadn’t got it right. Catherine Deneuve and her sister Françoise Dorléac were the only ones I ever saw actually wearing the hard-edged space-age clothes of Courrèges and Paco Rabanne and looking completely at ease and relaxed. Except perhaps the evening when Catherine was sitting enjoying herself with Bailey, Albert, and me in the club Régine’s and the waiter spilled an entire bottle of red wine over her new white sculpted Courrèges couture shift that must have cost thousands of francs.

If you went to L’Esquinade wearing the wrong thing, it was critical. You would be laughed at. They could be pretty bitchy, those fashion-mad French girls. I would never dare talk back to them. For me, the French were always so superior in matters of style. England was cool but never chic.

Although the late sixties were predominantly about Paris for me, there were events that frequently brought Albert—who had an office in Mount Street, Mayfair—and me back to England. By then we had also acquired a London pied-à-terre together, a modern penthouse in Ennismore Gardens, Kensington. The apartment was beautiful, but it never felt like a home to me. And though we were engaged for a while, Albert ended up spending most of his time in France, while I began to realize how much I preferred London.

My Paris moment had lasted four, maybe five years, during which time I had gone from having fairly long hair to a daringly short, drastic pixie cut—very much the copy of Mia Farrow’s in Roman Polanski’s hit film Rosemary’s Baby. Now the time had arrived for me to bid a final adieu. I was to leave France considerably wiser about clothes, and not a little bitter about false relationships and infidelities.

I soon learned that Albert, my handsome fiancé—the ring, appropriately enough, was in the shape of a snake—had been conducting a lengthy affair directly under my nose with Françoise Dorléac. This continued right up until her untimely death, when her car burst into flames on the road to Nice’s airport. She was rumored to have been on her way back to Paris to beg him to marry her when she was killed.

I was in bed with Albert the morning the phone call came through, telling him that she had died. So he didn’t just lose her at that moment. He lost me, too.

Read more from the full excerpt published by Vogue Online

Grace is available on November 20th from Amazon. Keep it in mind as a Christmas gift for any fashion-lovers you might know!