Most of the 75,000 residents of Oak Ridge, Tennessee had no idea they were processing uranium until the bombs dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. They had settled in the mysterious town, a “secret city”, with very little knowledge of what they would do there, other than the promise that their work was going to help end the war. Sure enough, on August 6th, 1945, a nuclear superbomb that the young men and women of Oak Ridge had helped develop, effectively ended World War II.

These photographs taken by the only authorised photographer for the entire town, Ed Westcott, documented life at Oak Ridge, from everyday moments of a seemingly normal suburban American town, to the residents performing their ‘tasks’ and ‘duties’ inside the secret nuclear facilities.

Oak Ridge is a name that was given to the 56,000 acres of land in Tennessee, West of Knoxville, at a cost of $3.5 million by the U.S. governmement. It was established in 1942 as part of the Manhattan Project, the massive top secret American, British, and Canadian operation behind the development of the atomic bomb.

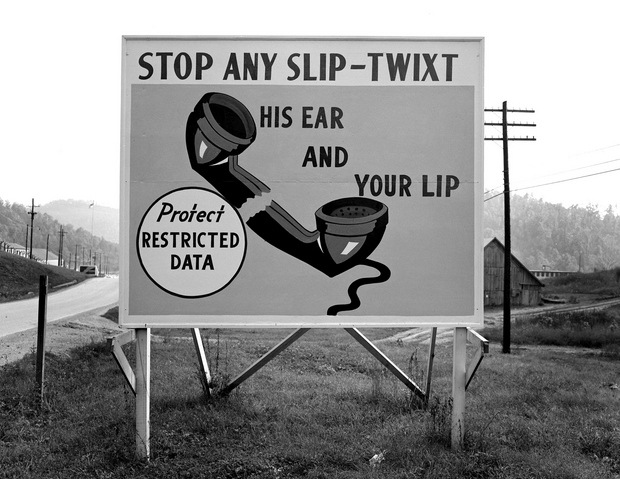

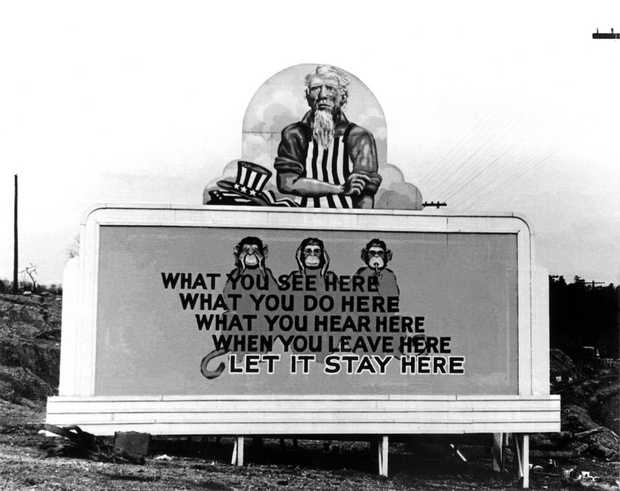

Billboards across the town reminded the residents of Oak Bridge to stay tight-lipped and motivated for the job at hand– even if they didn’t understand what they were doing it for.

“If somebody was to ask you, ‘What are you making out there in Oak Ridge,’ you’d say, ’79 cents an hour,'” recalled one resident¹.

Despite being open to the public, even the non-military part of the town of Oak Bridge was fenced in and guarded.

The vehicle inspection stop had no exceptions– everyone was searched, including the highest ranking military officials. Secrecy was top priority and if any of the residents and workers started asking too many questions about the nature of their jobs beyond the specific duties given to them, government agents would pay them a visit within a few hours and show them to the gates.

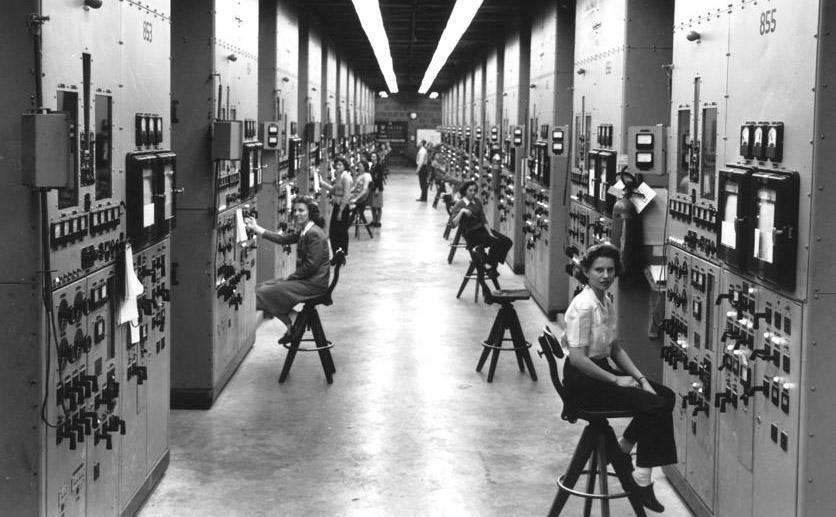

1946, Oak Bridge telephone operators getting ready for a shift change at the switchboard.

Workers weren’t allowed to say certain words, such as ‘helium’ or even the names of the equipment they were working with.

In the recently released book The Girls of Atomic City, author Denise Kiernan reveals the stories of the women who worked in the secret city. One worker, Colleen Black speaking to NPR remembers her factory days at Oak Ridge:

“You’d be climbing all over these pipes, and testing the welds in them. Then they had a mass spectrometer there, and you had to watch the dials go off, and you weren’t supposed to say that word, either. And the crazy thing is, I didn’t ask. I mean, I didn’t know where those pipes were going, I didn’t know what was going through them … I just knew that I had to find the leak and mark it.”

After the war, Oak Ridge worker, Mary Anne Bufard’s spoke to a radio show about her unusual mysterious duties:

It just didn’t make any sense at all. I worked in the laundry at the Monsanto Chemical Company, and counted uniforms. I’ll tell you exactly what I did. The uniforms were first washed, then ironed, all new buttons sewed on and passed to me. I’d hold the uniform up to a special instrument and if I heard a clicking noise — I’d throw it back in to be done all over again. That’s all I did — all day long.

Of course Mary would later learn she was screening for radiation.

Not understanding what they were doing or knowing what it was for didn’t do much to help morale in the factories, causing rumours to spread and suspicion to arouse. Workers were continually told they were doing a very important job but couldn’t see the results of their duties. One notable theory amongst workers was that Oak Ridge was a prototype socialist community masterminded by Eleanor Roosevelt as part of her plan to turn America communist.

Put people to work in a factory, tell them not to ask questions, throw in a few propaganda billboards around the place and you start to see why such theories arose.

So what do you do to fix a problem such as low morale in your secret city?!

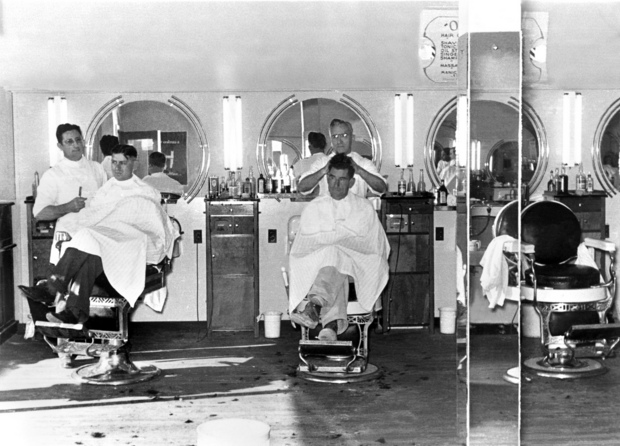

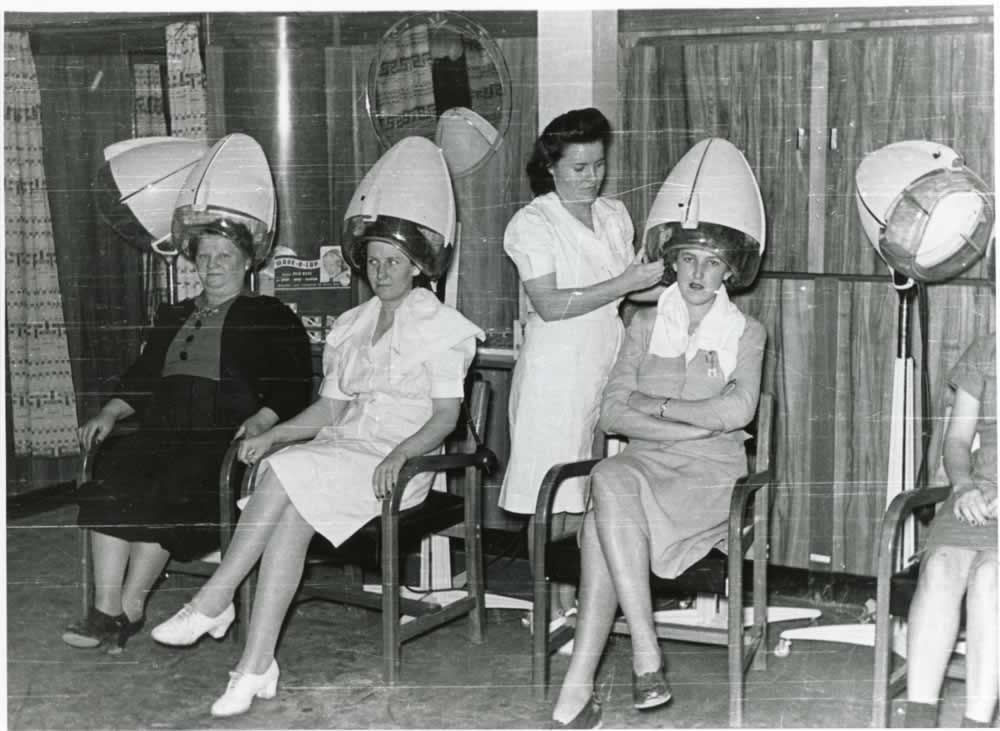

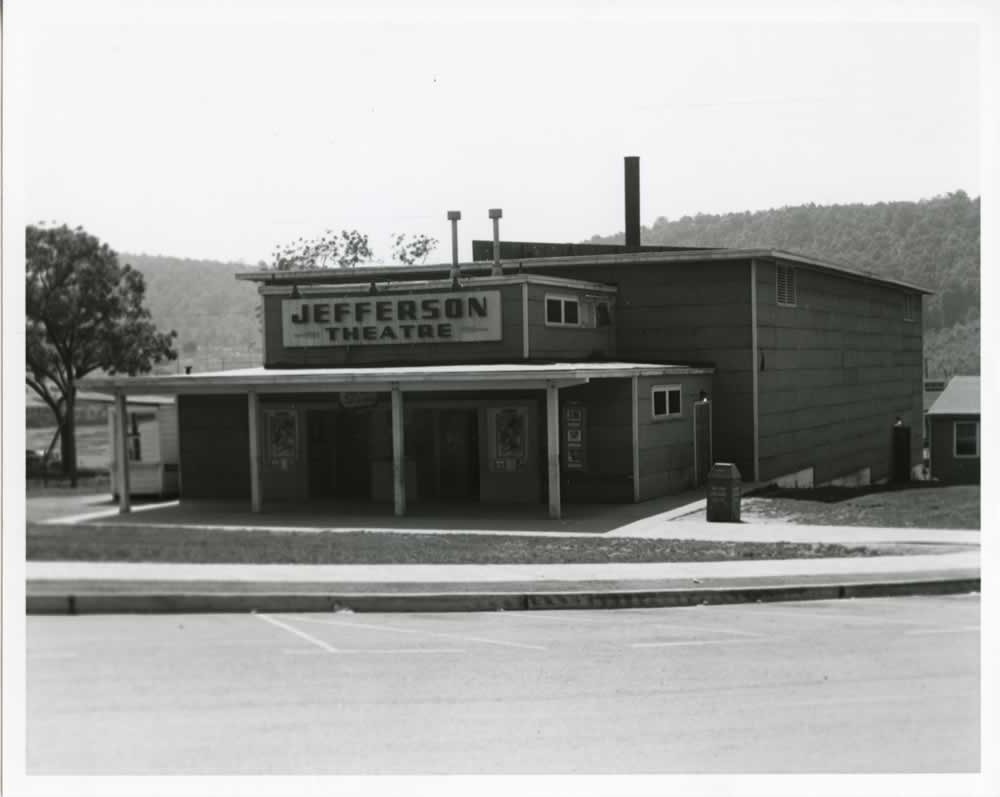

You create the ideal wholesome American suburban town, complete with roller-skating rinks, bowling alleys, sports teams, theatres, shopping & more, of course!

Oak Ridge residents Louise Cox, Vilma Strange, and Marilyn Angel at the Oak Ridge swimming pool in 1946.

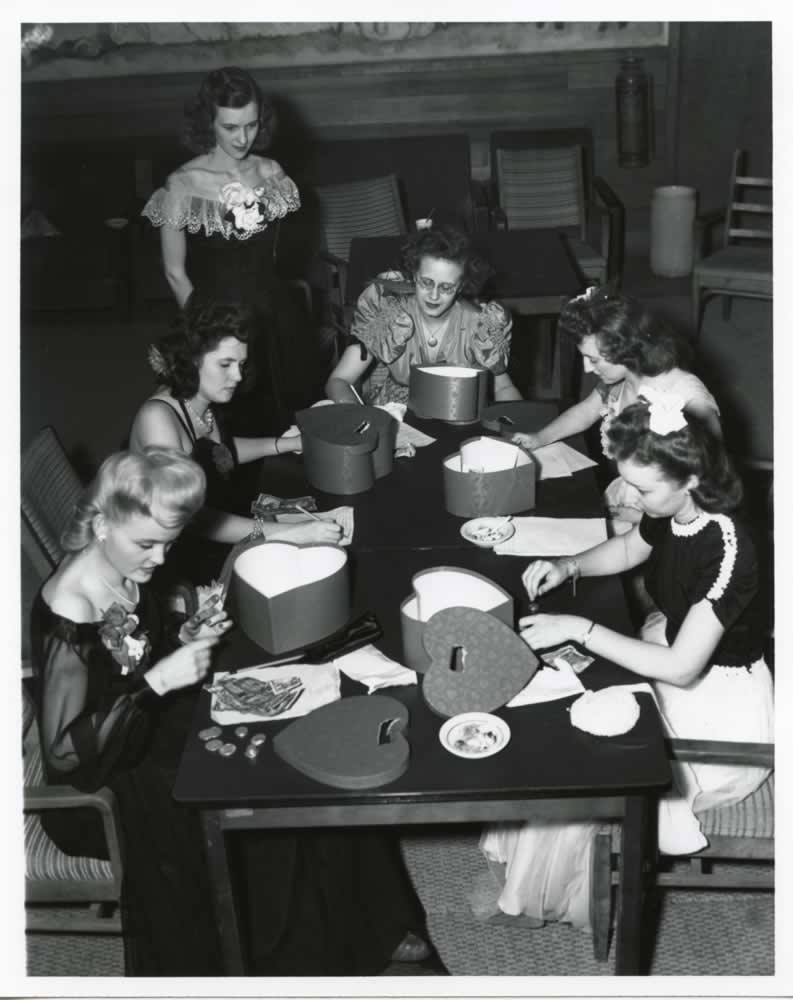

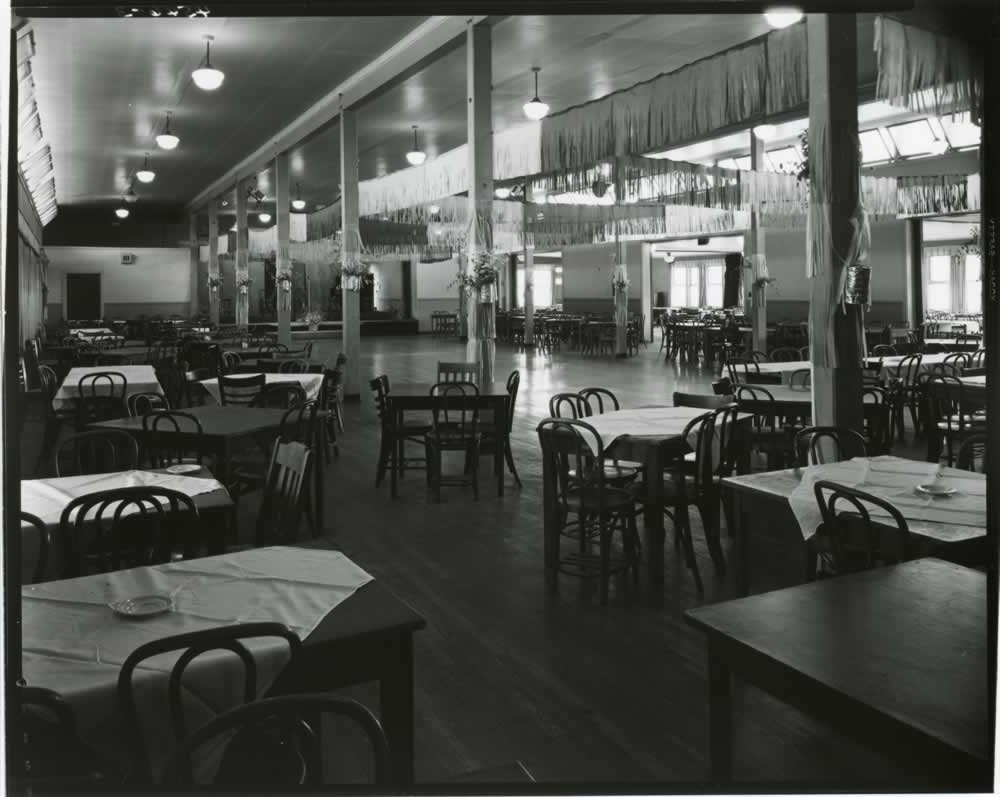

Counting money/votes at the Ford, Bacon, & Davis Valentine Dance. 1945

“We were very young,” former worker Colleen Black told NPR. “We were so young that we didn’t have a funeral home! And so you got acquainted and you went to the dances on the tennis courts and the bowling alleys, and the recreation hall.”

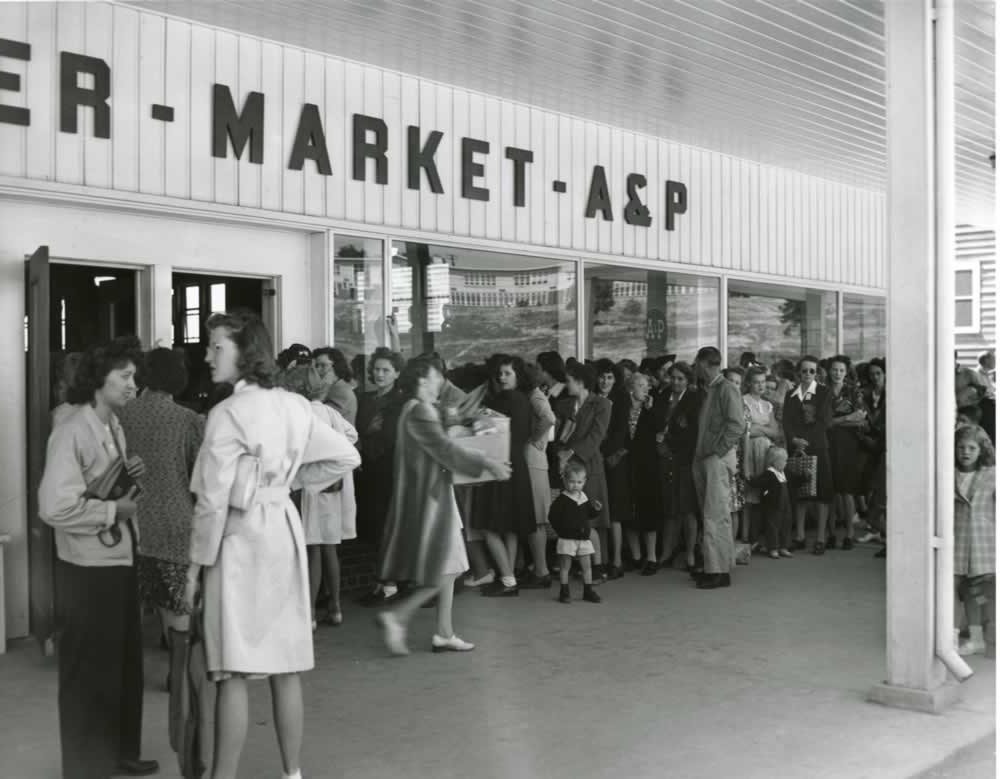

Lines outside the City Center A&P.

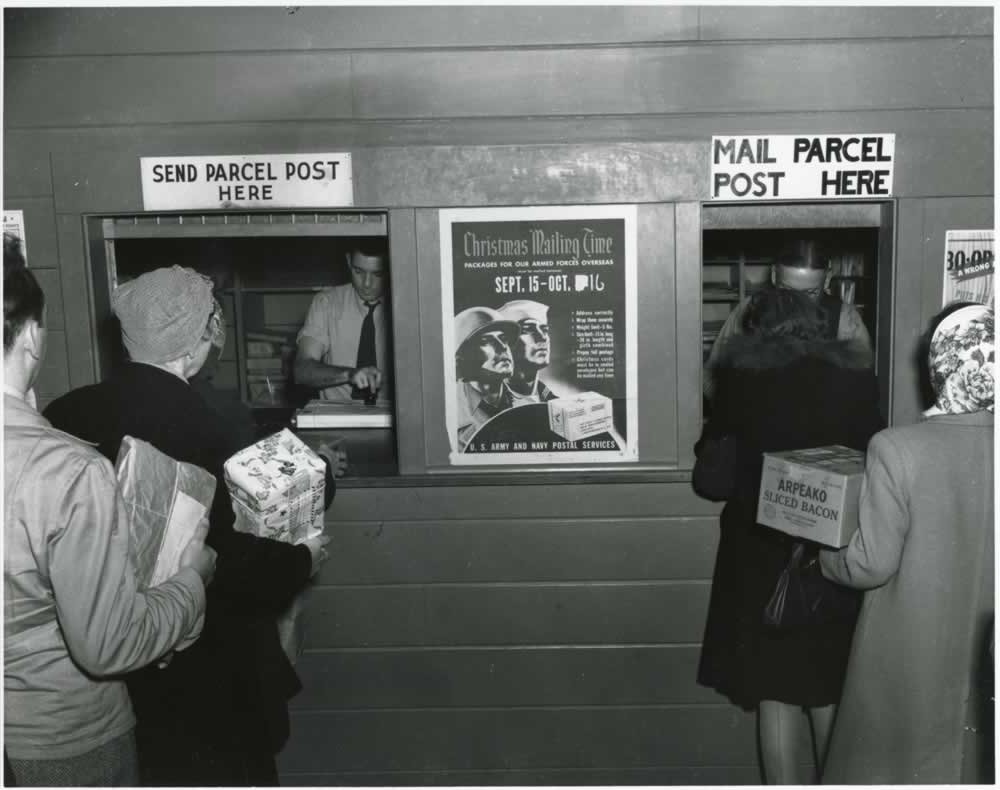

Another line at the Oak Ridge Post Office.

Your average bus stop? (With routes to the local uranium enrichment facilities). By 1945, Oak Ridge was home to 75,000 people with one of the largest bus systems in the entire United States. They were also using more electricity than New York City.

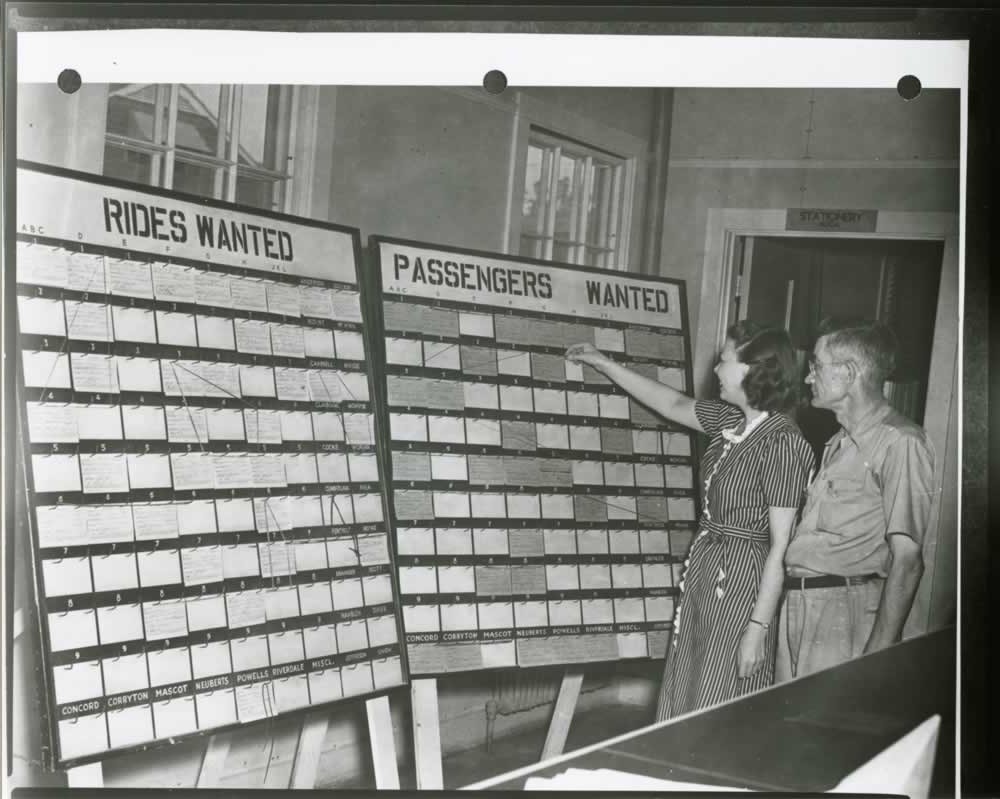

Setting up the bus route? 1944

Shirley Davis and an unidentified woman in the city directory office, 1944

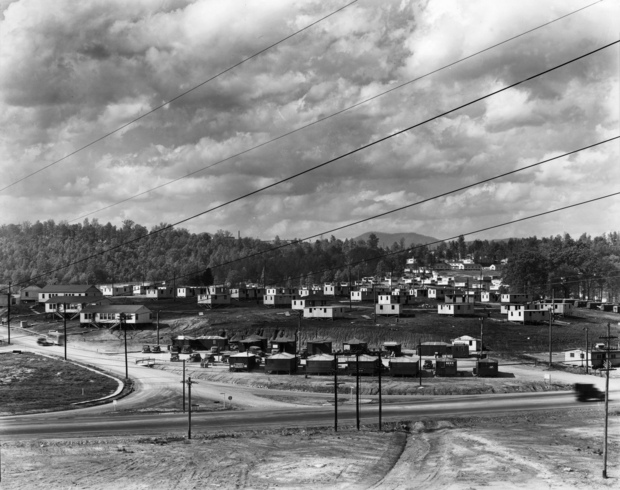

Housing for Oak Ridge residents was allocated by the government using a lettering system according to the status of the workers and the size of their families. Higher ranking workers with bigger families would have been typically allocated an “F” home, a two story four-unit structure. There were also “A” houses (two story duplexes with three bedrooms) and “B” houses (smaller single story homes with two bedrooms).

Then there were the “flat tops”; typically temporary structures for young newcomers, although chronic shortages of housing and supplies during the war years probably made them a more permanent solution for many.

Unidentified clerks waiting on woman in the dorm room assignment, 1945

This abandoned cabin was photographed in 1947, a few years after the U.S. government took over the 56,000 acres in East Tennessee. It had previously been a farmland where some families were given just two weeks’ notice by the government to vacate the farms that had been their homes for generations. Others had settled there after having already being displaced by the government in the 1920s and 30s to make way for the Great Smoky Mountains National Park or the Norris Dam.

Oak Ridge children playing in an atom plane, 1945.

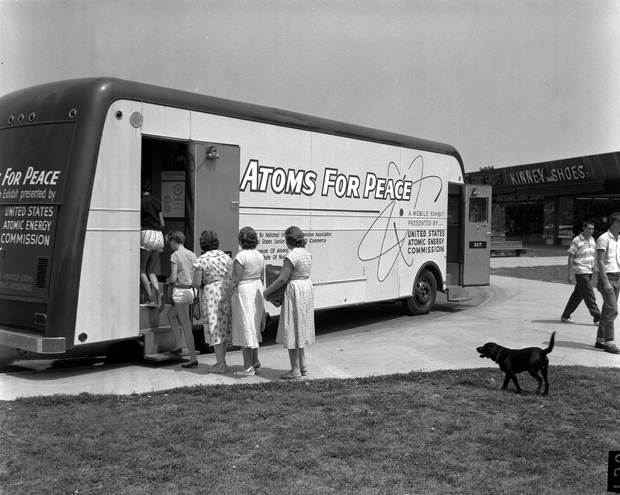

After the bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, several physicists who participated in the Manhattan Project founded the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, to begin an urgent educational program about atomic weapons.

For the many workers of the Manhattan Project who had been the enriching uranium used to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this V-J day celebration in downtown Oak Ridge in August of 1945 would have been the first time, along with the rest of the world, that they learned of the existence of a superbomb.

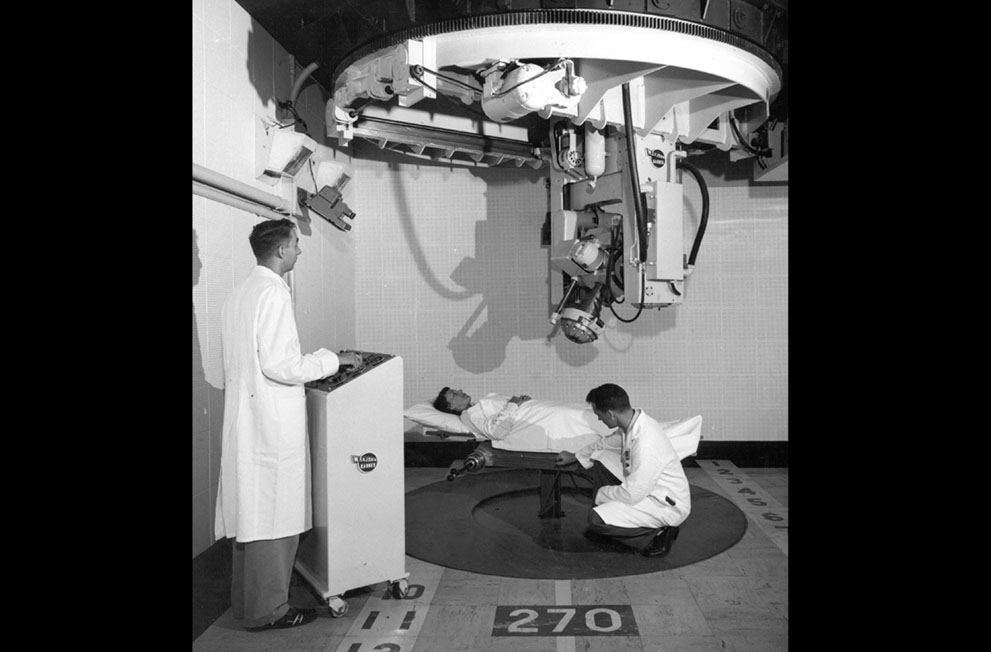

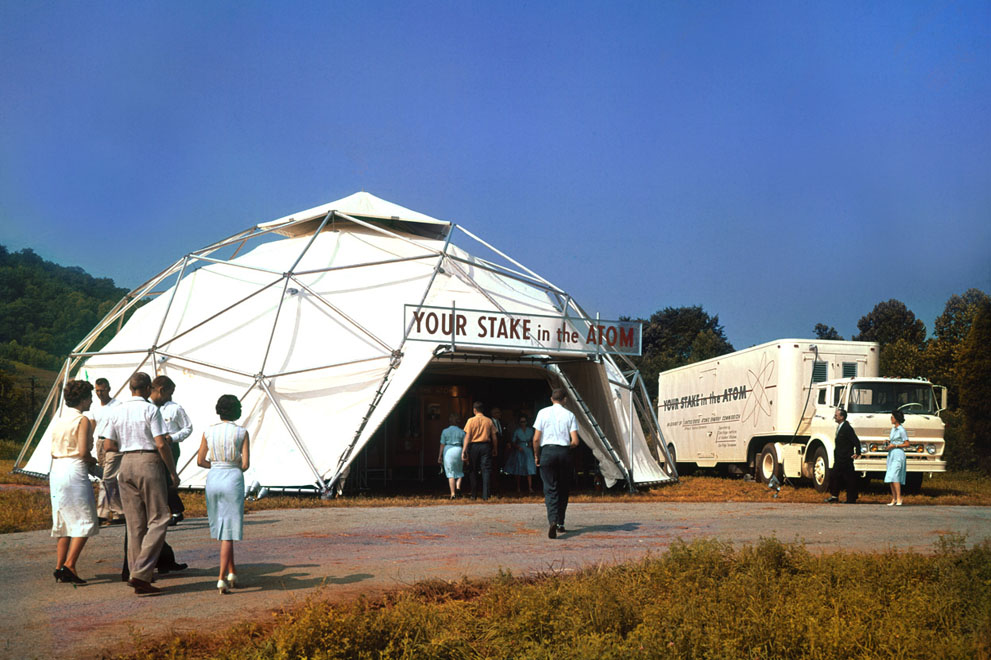

Two years after World War II, Oak Ridge was demilitirized and shifted to civilian control. In 1966, an American Museum of Science and Energy was founded to give tours of the control room and reactor face.

“In 1983, the Department of Energy declassified a report showing that significant amounts of mercury had been released from the Oak Ridge Reservation into the East Fork Poplar Creek between 1950 and 1977.” While a federal court order was given to bring the Oak Ridge Reservation into compliance with environmental regulations, finding out the current status of this may call for an Erin Brockovich moment on a rainy day.

The historic K-25 uranium-enrichment plant wasn’t demolished until May of 2013 (pictured above), while the Y-12 facility, originally used for electromagnetic separation of uranium, is still in use for nuclear weapons processing and materials storage. And the U.S. government is still the biggest employer in the Knoxville metropolitan area. As of November 2012, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, is also home to the world’s fastest supercomputer.

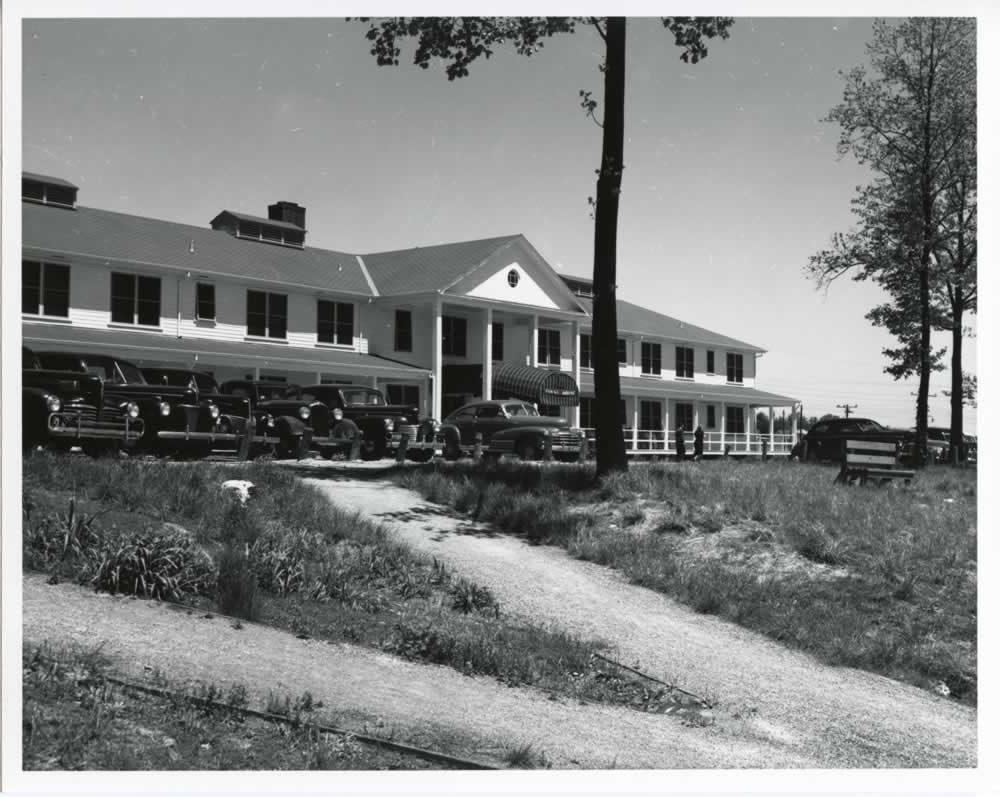

But what is left of that old residential town for the workers of Oak Ridge? This old hotel known, pictured above, as the Alexander Inn, picture above in 1947 is one of the few remnants of the original secret city.

Photo (c) Ethielg on Flickr

Built during the Manhattan Project to accommodate official visitors including dignitaries and many important nuclear physicists, the hotel finally closed its doors in the mid 1990s. Since then, it has been allowed to fall into serious disrepair.

Was the Manhattan Project America’s very own Nineteen Eighty-Four? Or were the residents of Oak Ridge the unsung heroes of World War II?

Sources: The Photography of Ed Westcott, NPR, The Nuclear Secrecy Blog

:::

In the immediate postwar years, the Manhattan Project would go on to conduct testing of 23 nuclear bombs at Bikini Atoll, which permanently contaminated the islands and displaced its indigenous residents.

THIS MIGHT ALSO INTEREST YOU: