The Maginot Line, considered by many to be one of the greatest and most expensive military mistakes of all time; a name rarely spoken of today except to recall something that people hope will prove effective but instead, fails miserably.

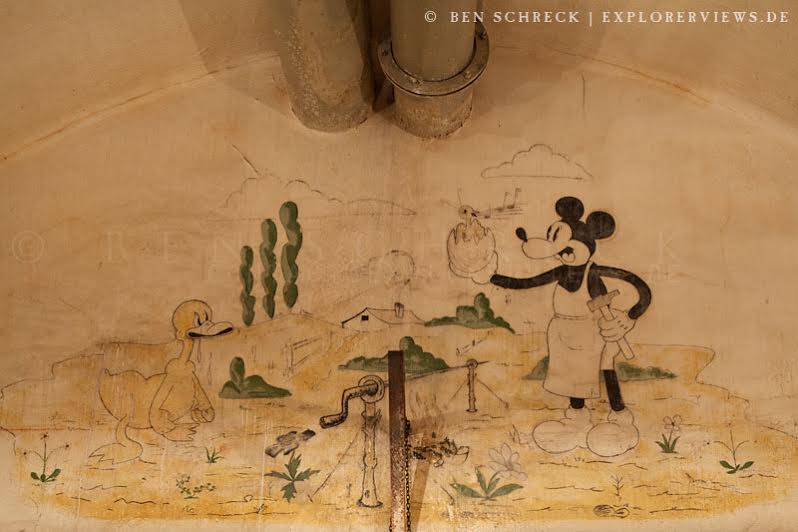

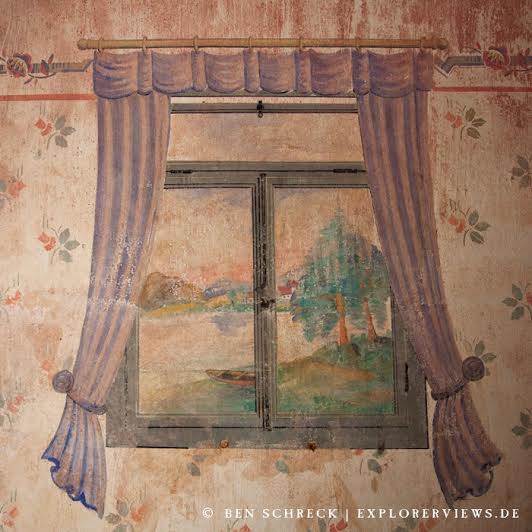

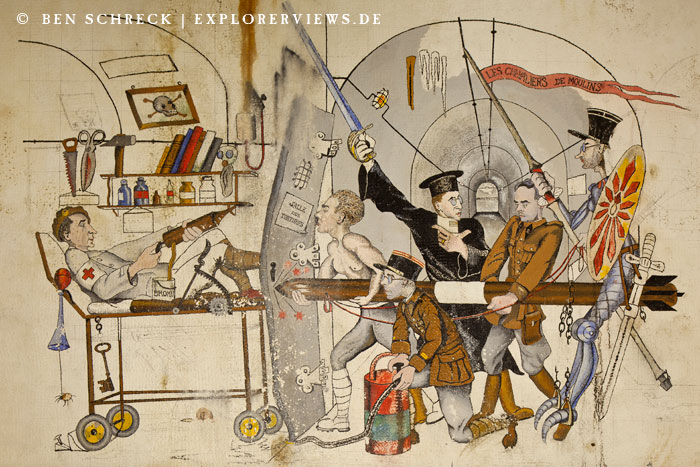

But here, inside the forgotten underground bunkers that line a defensive wall built by the French between the two world wars, extending from the North Sea to the Mediterranean– art, of all things, over all these decades, has prevailed.

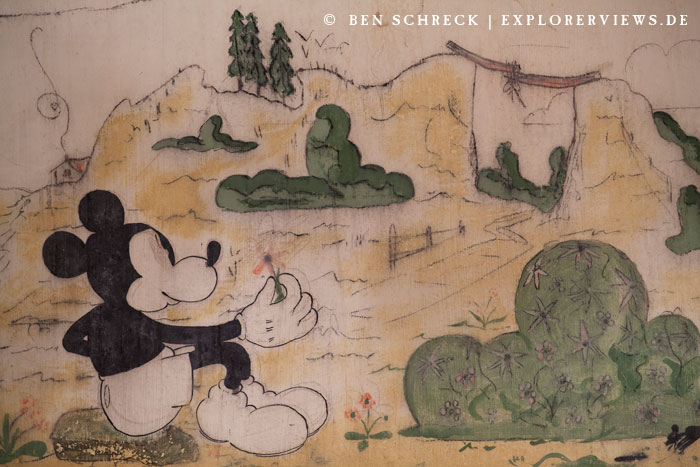

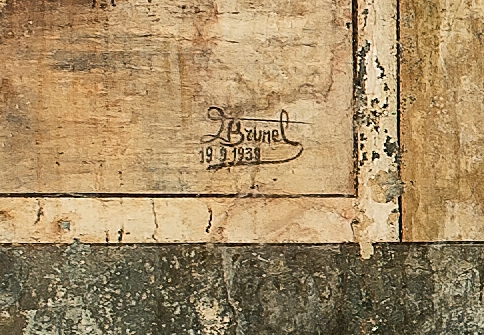

Our visual guide is Ben Schreck, photographer and urban explorer, who captured these preserved artworks inside the Maginot Line, access to which is extremely rare and largely forbidden to the public today.

Rewind to 1937, and these facilities were first being put into operation, a line of concrete fortifications, obstacles, and weapons installations that France constructed along its borders with Germany to prevent a major attack.

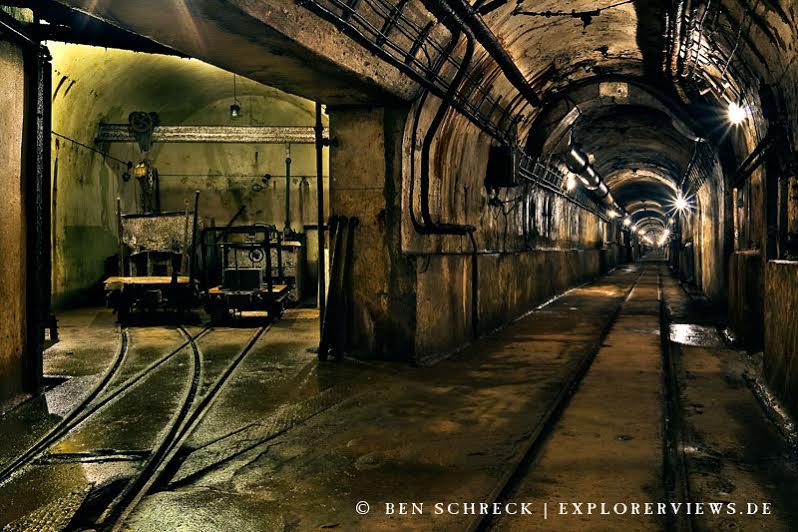

“Life in the Maginot Line was not pretty. In reality, it was cold, damp and dark for the soldiers,” explains Ben. For some of the men stationed there, artists in soldiers uniform, the opportunity presented itself to make the bare, windowless concrete walls of their bunker somewhat friendlier.

Fresco paintings of course take time and patience, something the soldiers stationed at the Maginot line had a lot of…

The problem was, despite the defence system being armed to the teeth and ready to take on Godzilla if he showed up at the German border, nothing ever actually happened at the Maginot Line. It cost an unmentionable chunk of the French GDP to build the initial line and while it did theoretically prevent a direct attack, the Germans army just went around the line through Belgium, conquering France in under six weeks.

With the help of aerial photos of the fortresses under construction and spies they probably had placed in the work crews, Germany had stationed a dummy army outside the strongest part of the Maginot Line and the French defence system was spectacularly outflanked. The Franco-Belgian border was a weak point, spottily fortified, mainly because the French ran out of funds. The huge cost it had already taken to build and maintain the “genius” fortification, had also meanwhile led to other parts of the French armed forces being crucially underfunded.

The strategy of the Maginot had been a fantasy, doomed from the start, flawed in its inconsistency, truncated at its most vulnerable points. But there had been a lot of fantasy associated with the Maginot Line in the years leading up to the war.

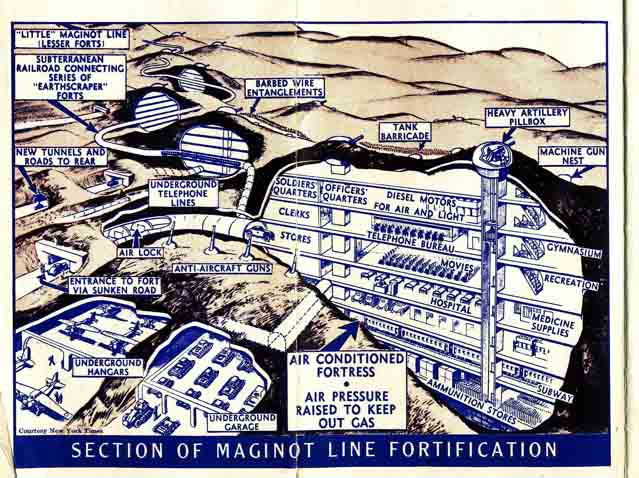

Here is a New York Times artist’s pre-war impression of the Maginot Line (it’s wildly inaccurate).

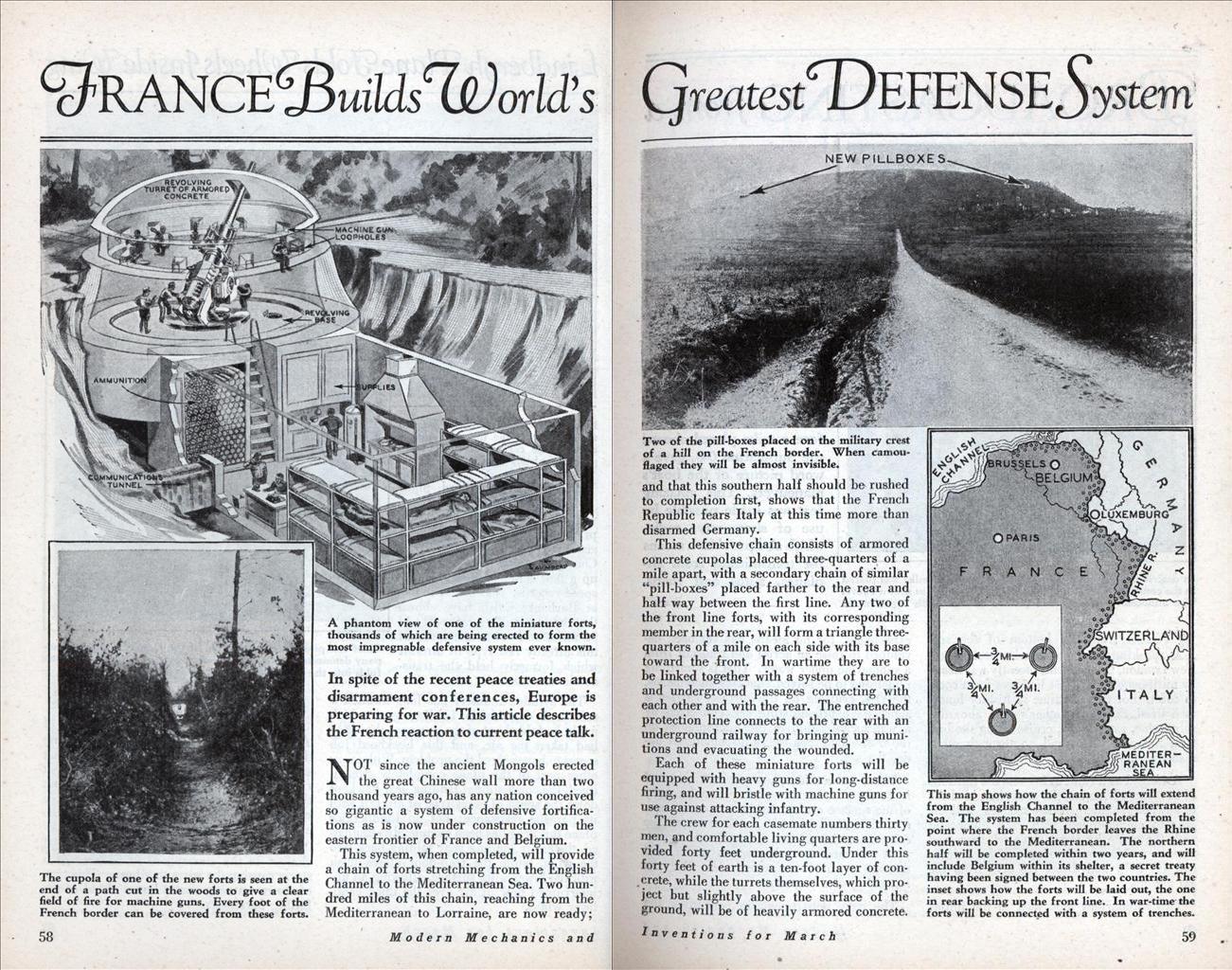

The following article from the archives of Modern Mechanics and Inventions gives a more accurate illustration of the defence system’s pill boxes with the retractable turrets for 75-mm artillery. The title of the article is probably less accurate.

After the surrender of France, the Maginot Line was handed over to the Germans and later, the facilities were again used by the French military until the mid 1960s, when it was abandoned and left to decay. Some parts were auctioned-off to the public which have been turned into wine cellars, a mushroom farm and even a disco at one point, according to the Smithsonian. A few of the bunkers have been turned into museums, which can be visited in the summertime.

Only one fortification reportedly remains in active service, the Ouvrage Hochwald, while the others have been closed, no longer accessible– unless of course you know how to find another way in. “It is forbidden to go there,” Ben tells me, “But if you know the entrances and you want to do it, you’ll have to go ten to fifty meters below ground. There is no light or power down there of course so you’ll have to light your own way.” Although the state can’t afford to guard the Maginot Line anymore, Ben assures me, “It’s certainly not fun to be caught there.” Gangs are known to loot the last of the copper cables, giving the police a reason to show up now and again.

“But the artwork down there? Nobody takes care of that.” While the two Mickey Mouse paintings and the fresco depicting soldiers bursting into the underground bunkers of the Maginot Line are part of the converted museum, Bois de Bousse (also known as Fort aux Fresques), all the other artworks photographed by Ben are not open to the public.

“The works have somehow survived through all these decades, but nevertheless, I saw significant traces of decay. In the foreseeable future, I imagine most of the works and thus the traces of the people who were there, will no longer exist.”

Discover Ben Schreck’s exploration of the Maginot Line / become a fan on Facebook.

:::

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: