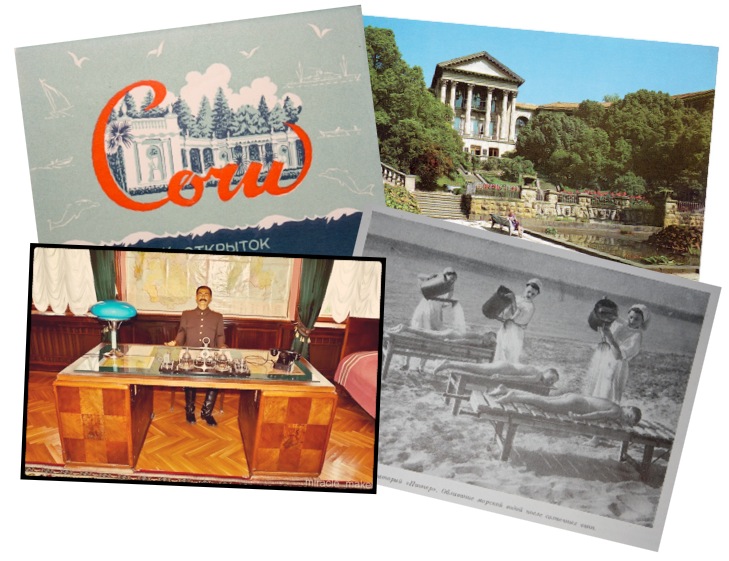

Sochi, a Russian city on the Black Sea, is known for being a controversial host of the 2014 Winter Olympics, but I thought we might take a look back at the “Florida of Russia”, when it was still a socialist holiday resort for Soviet workers hoping to experience a semblance of the utopian future they had been promised. Of course, Sochi was also once the summer playground of Jozef Stalin himself, and his vacation home still stands, perfectly preserved and untouched on the outskirts of the city– you can even visit it.

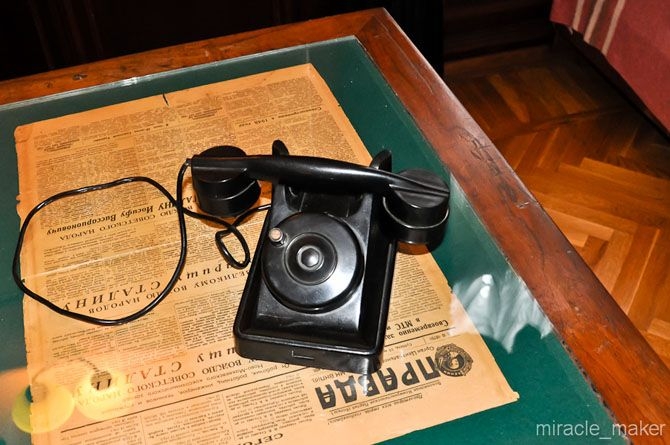

When in Sochi, don’t forget to call in on Stalin…

Painted in camouflage green to seem invisible from the air, this was one of Stalin’s eighteen country houses (or dacha). Today it stands as a museum situated on the grounds of a hotel and former soviet resort, the Zelenaya Roscha VIP hotel. It can also be hired out as a hotel and conference centre, although I don’t see it getting a huge amount of use as an events venue.

Museum visitors can expect to find a disturbing life-like waxwork figure of the dictator as well as a bullet proof couch where he sat watching his films.

His swimming pool, chess set and even his personal cue in the billiards room have all been left in the house just as they were…

But it wasn’t just Stalin who summered in the subtropical seaside town. If a Soviet worker earned the right to be granted the putyovka, the critical document for a vacation provided by the worker’s trade union, they would have the chance to see Sochi.

“A trip to Sochi as a reward for hard work or to recuperate from an injury or illness was the best thing that could happen to a Soviet at the time,” writes the multimedia reporting site, The Sochi Project.

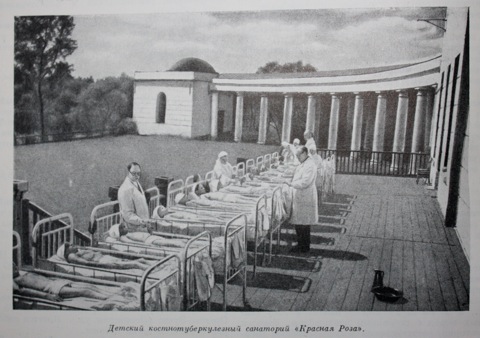

Largely paid for by the state, workers could take a leave to Sochi for up to four weeks and stay in “worker palaces” and “factories of health”, rather unfortunately known as a sanatorium.

A little bit like being sent to summer camp as an adult (I said a little bit), the sanatoria in Sochi came in all shapes and sizes, some built specifically to accommodate mine workers or soldiers of the Red Army, but all intended to promote Stalinist views and Soviet culture. Workers were encouraged to use their vacation time productively; to restore the body and mind to health with exercise, “curing” treatments, healthy meals, concerts and educational programming. In Sochi’s sanatoriums, the goal of this recreational leave was to literally, ‘recreate’ the Soviet worker.

A curator of an exhibition on the “Soviet House of Rest“, William Nickell refers to an old Russian guidebook claiming that while capitalist societies exploited workers, the Soviet government was devoted to their care: “Every new success in this sphere confirms the ascendency of socialist humanism, the effectiveness of Stalinist care for the individual.”

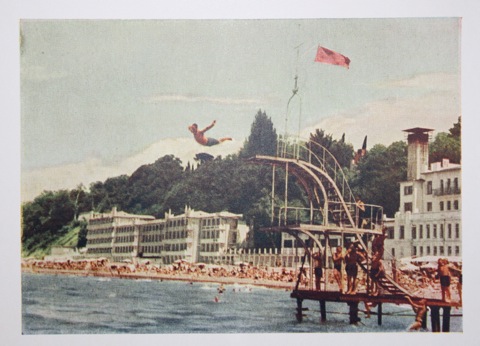

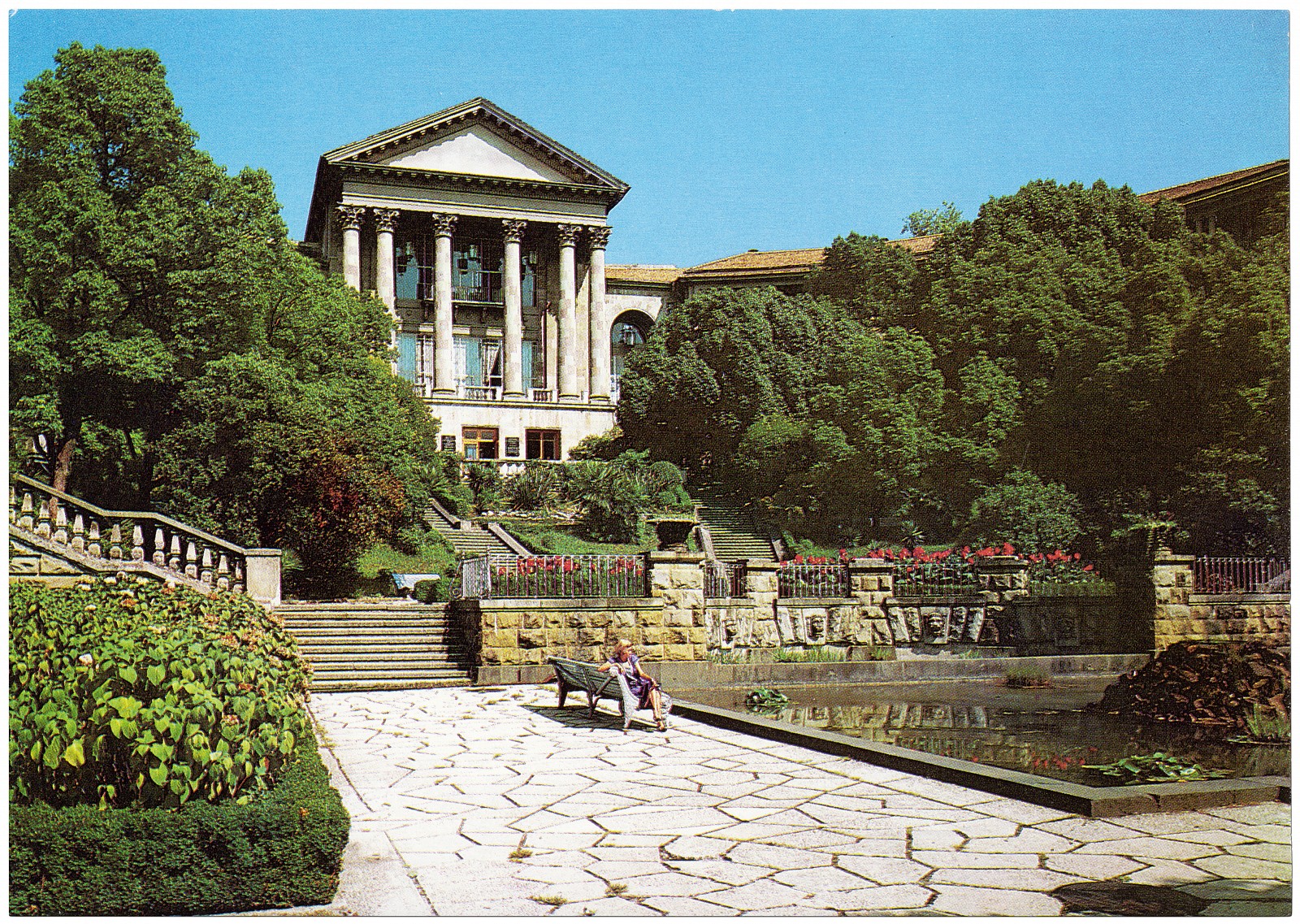

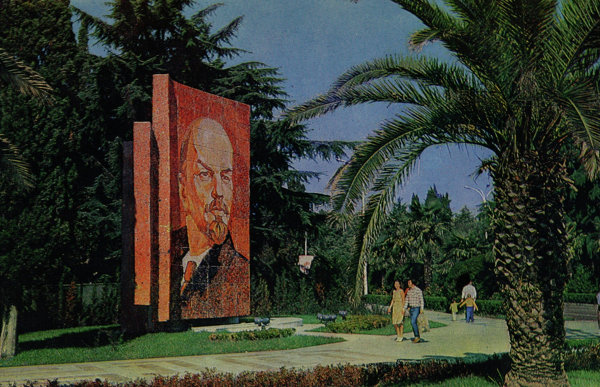

Sochi was once entirely laid out like a giant utopian park; an eden of flower-lined roads dotted with Neo-classical buildings, fountains and statues. With health being a high priority on the sanatoria’s agenda, sporting events and competition have always been a popular tradition in Sochi.

Pictured above: Metallurg, on Kurortny Prospekt, one of Sochi’s most famous sanatoria built to accommodate metalworkers, located next to the enormous Red Army sanatorium and Ordzhonikidze, the sanatorium for miners.

Postcards of Sochi in the 1970s & 80s…

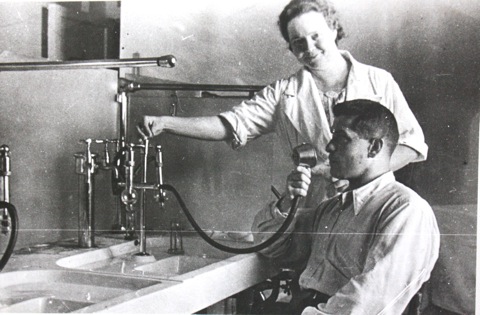

Services and treatments at the sanatoria varied depending on which trade union a worker belonged to. Pictured below, a mineworker receives oxygen treatment to “help clean out and strengthen their lungs.”

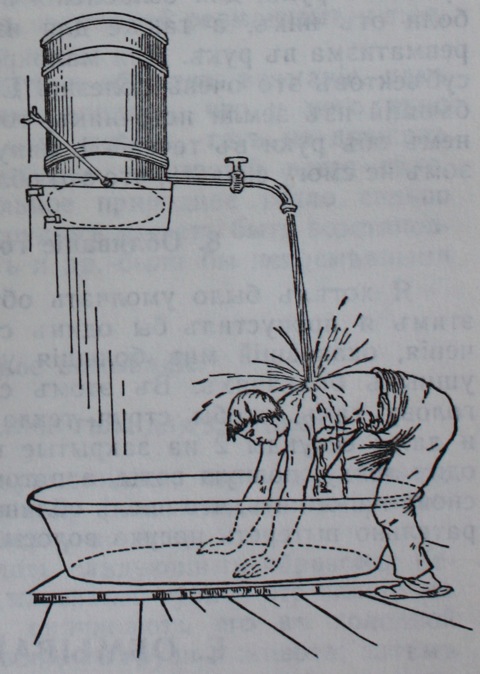

“The taking of waters” was also a key treatment for Soviet workers on their holiday….

“Water therapy was administered by numerous means: bathing in the ocean, in mineral spas or hot springs, or by drinking. Doctors prescribed these treatments on all levels: how many minutes per day of bathing in the sea, which spa treatments to take, and what mineral drinking water might provide the best therapeutic effects for a given patient,” explains Soviet House of Rest exhibition curator, William Nickell. “Hydrotherapy, in the form of saunas, whirlpools, and jet sprays, was also used for the treatment of various muscular or rheumatic ailments.”

As for the “resort” rooms? You couldn’t exactly call them luxury…

“There was not much to do in the room,” writes Nickwell, who spent time in Sochi in 1989 and 2009. “You were not supposed to spend a great deal of time here, but instead to spend time socially. There was a radio, but no television. The radio had one dial—for volume only. The programming was centralized, typically emanating from Moscow. At the resort you could always hear the chiming of the hours and quarter hours, prefaced by the opening notes of Moscow Nights.”

Fast-forward to the 21st century and Sochi’s sanatoriums are relics of a bygone era, that struggled to survive in a small resort town making way for the most expensive Olympic games in history…

This is the Metallurg sanatorium today (seen earlier in the 1980s), pictured by The Sochi Project, a multimedia online report uncovering “the real Sochi” by journalists Rob Hornstra and Arnold van Bruggen. Despite it’s rather sorry-looking state, the report claims that thousands of Russians still flock to Sochi to take vacations in a sanatorium organised by their unions, employers or factories. But new shadows over the Soviet worker palaces are looming …

A new apartment building next to Metallurg, Sochi, Russia, 2009.

Most of the sanatoria has been torn down or converted into four star hotels or modern skyscrapers due to wealthy Moscovites cashing in on the Olympics.

Curing equipment still used in the Metallurg sanatorium and below, the Metallurg sanatorium’s disco…

Despite the Winter 2014 Olympic Games being one of most expensive games of all time, the benefits can not be seen in Sochi, as the park and many of the hotels built lay empty with nothing to show bar the extreme costs of their ‘upkeep’. An image the the Sochi Project predicated as they once wrote “Never before have the Olympic Games been held in a region that contrasts more strongly with the glamour of the Games than Sochi.”

Discover The Sochi Project

Sources: The Soviet House of Rest / The Sochi Media Centre / English Russia