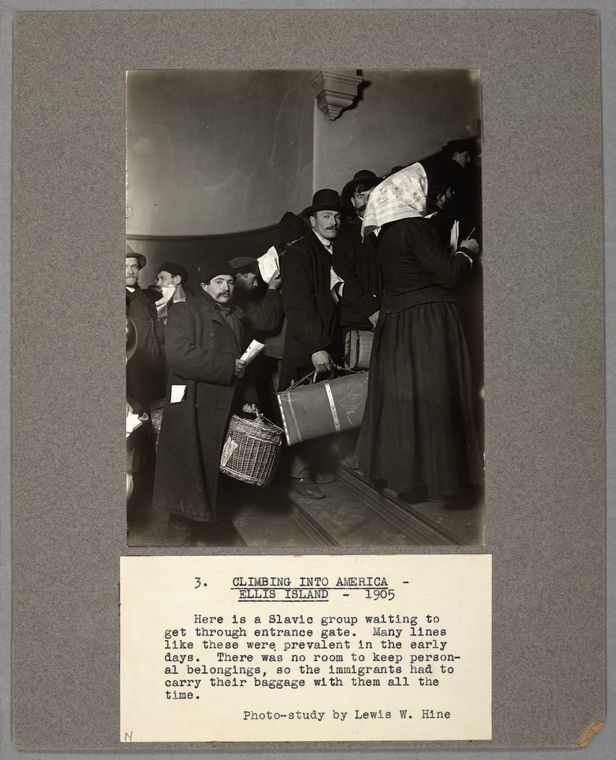

“Amidst crowds of anxious immigrants milling about, Hine had to locate his subject, isolate [them] from the crowd, and set the pose-almost always, because of the language barrier without words. He had to set up his simple 5 x 7 view camera on its rickety tripod, focus the camera, pull the slide, dust his flash pan with powder, and through his own look and gesture try to extract the desired pose and expression. With a roar of flame and sparks, the flash pan exploded, an exposure was made, and beneath the protective cloud of smoke which blinded everyone in the room, Hine would pack up and leave. A second exposure was out of the question; one shot was all he had.”

– Walter Rosenblum, America & Lewis Hine (1904-1940)

The full extent of Lewis Hine’s work is some of the most uncelebrated and forgotten examples of photographic mastery you can probably find tucked away in the American public archives.

Unlike most early documentary photography from his time, Hine’s photographs were curiously compassionate, unusually humanist and raw. It often feels as though he must have assumed the guise of a typical roving documentary photographer of the era just as a means to secretly encourage social consciousness. Later in his career, he would in fact take to wearing disguises in order to gain inside access and get the shots he needed to uncover the reality of the not-so-dreamy American dream.

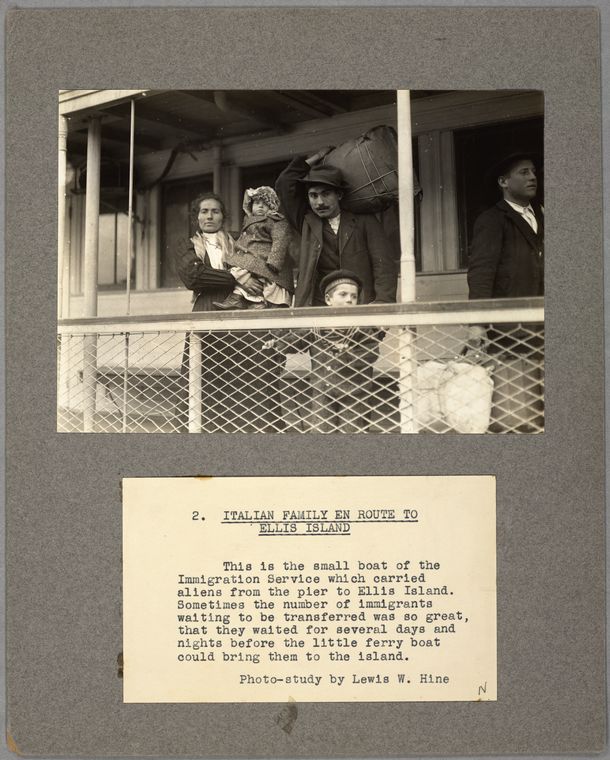

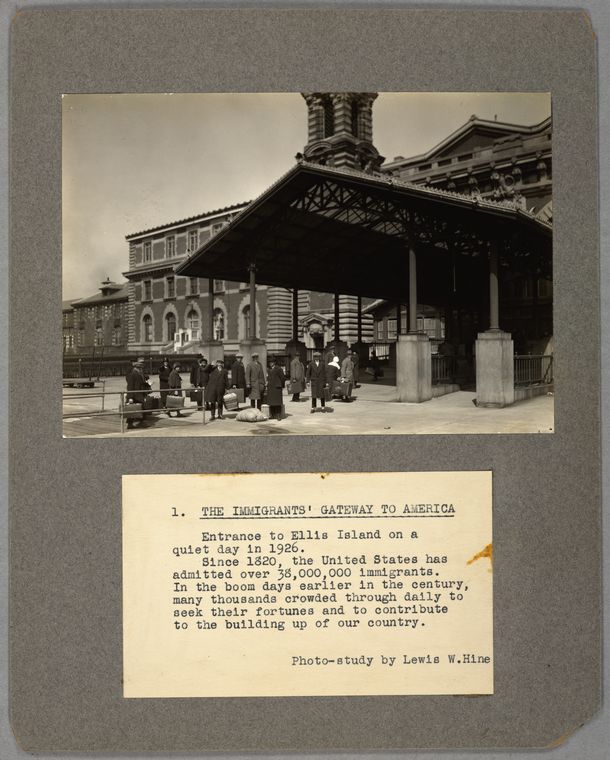

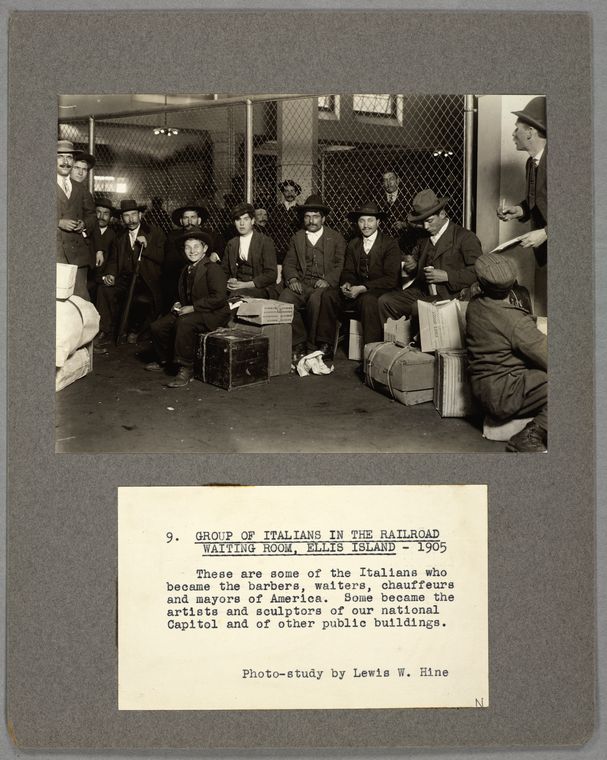

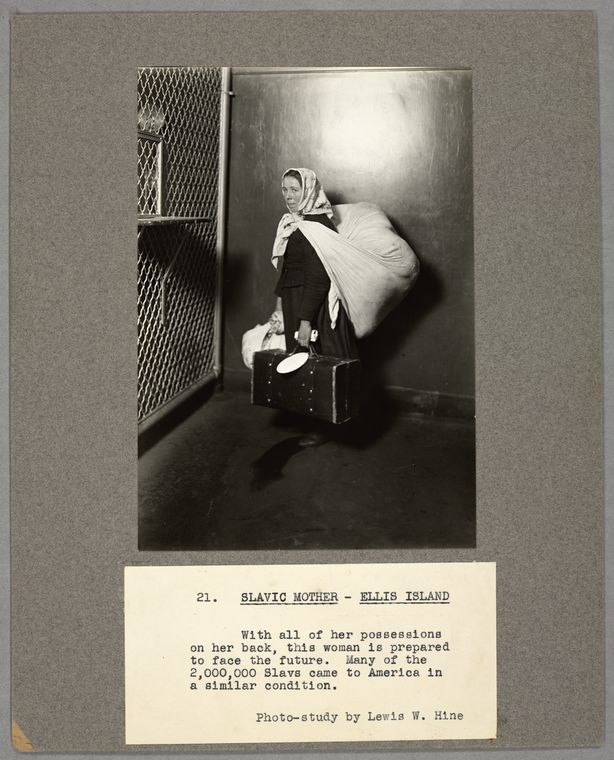

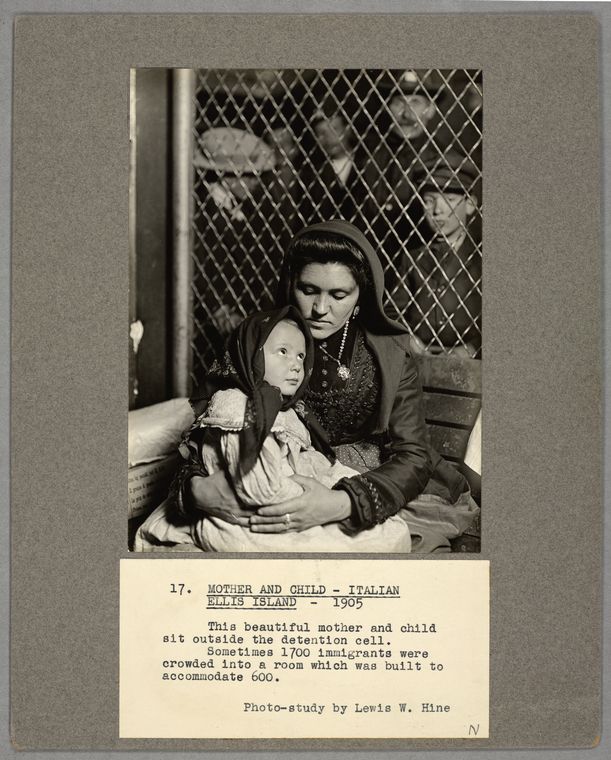

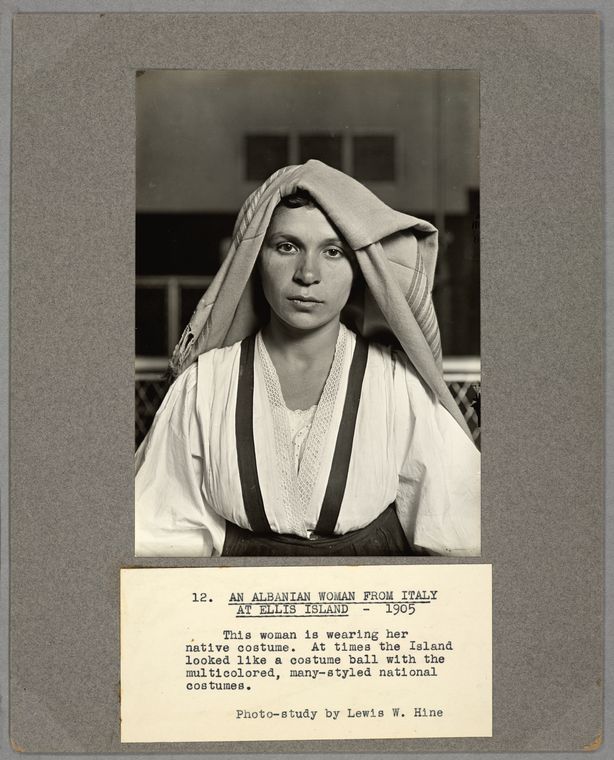

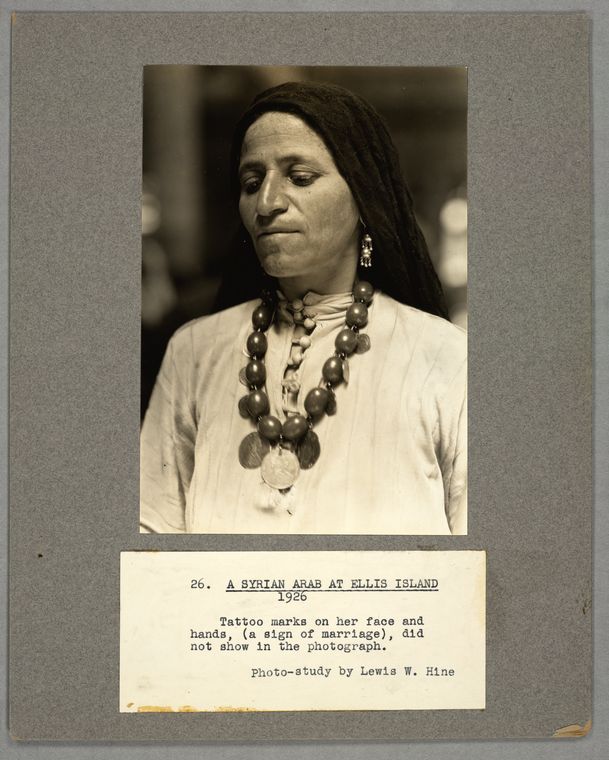

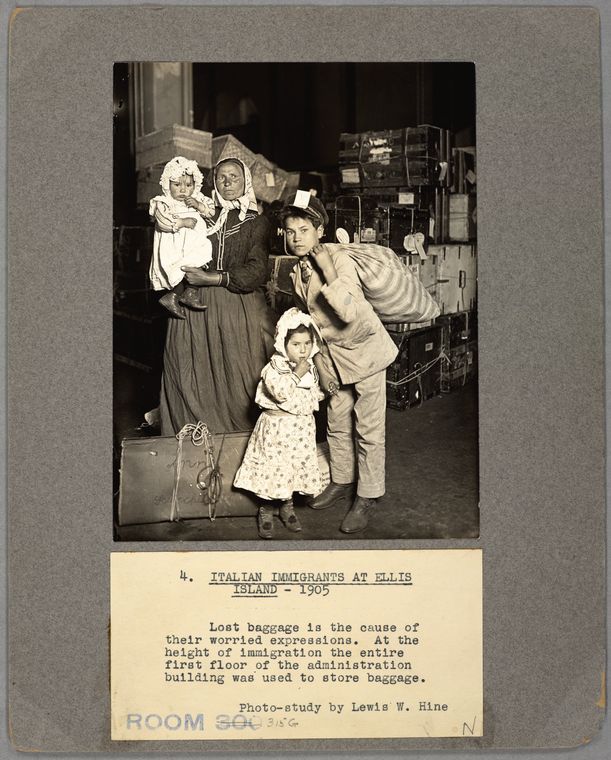

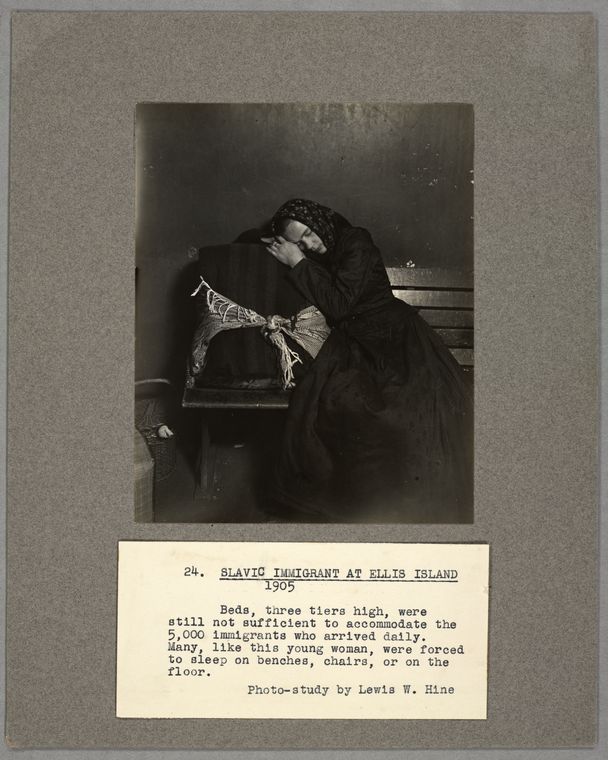

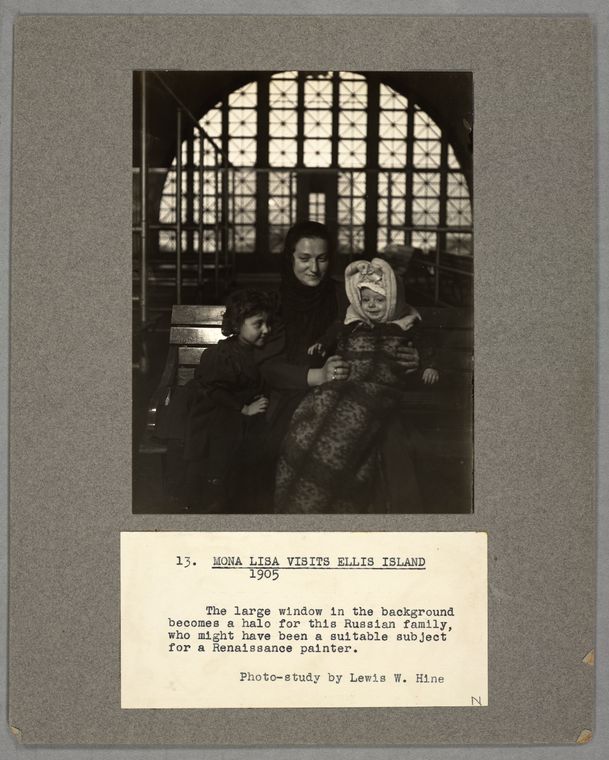

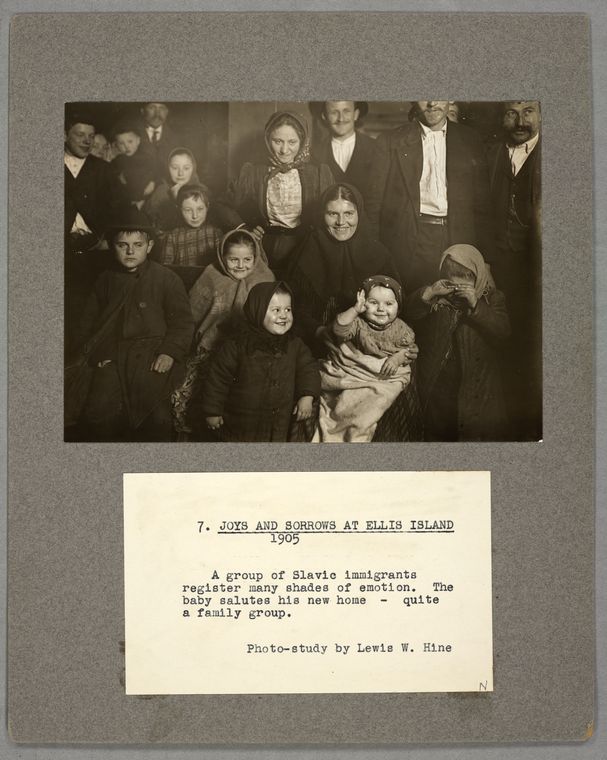

When he was teaching in New York City at the dawn of the 20th century, Lewis Hine began taking his students and his photography equipment to Ellis Island in New York harbour where thousands of immigrants were arriving everyday; lone travellers and entire families alike, who had fled their homelands and crossed an ocean in pitiful conditions in the hope of finding new beginnings in a strange land. But for Hine, this wasn’t just about documenting immigration for public records. His portraits were about paying homage to these people, whose hopes and dreams would in most cases, sadly never match the reality of their future in America.

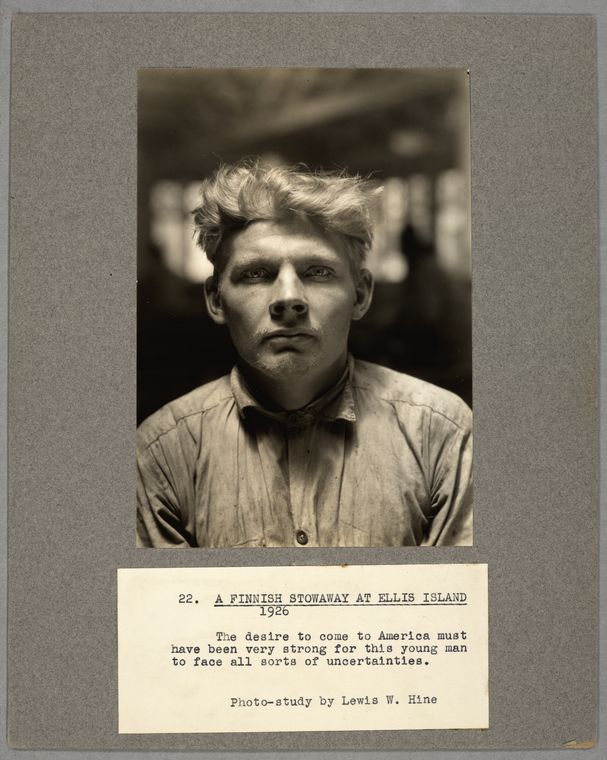

It was no accident that he chose such a significant moment in American history to take up photography. Despite being born into an era of society sustained by immigrant exploitation, Hine clearly recognised the immorality and the oppression better (and earlier on) than most. While for so many, Ellis Island was seen as a gateway to a new life in America, for Lewis Hine, it was his gateway to an obsessive lifetime career in exposing the human injustices that awaited in the new world.

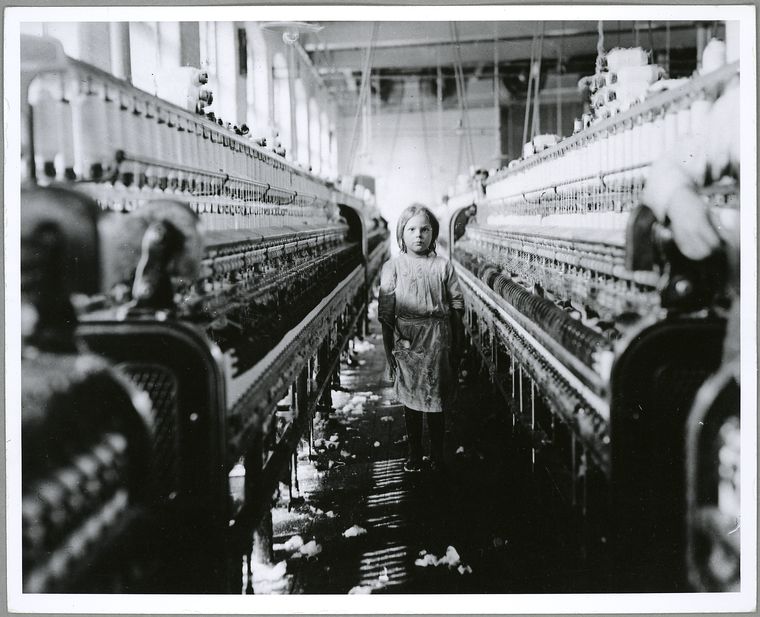

“It quickly became evident that his Ellis Island ‘Madonna’ the proud Jew, and the beaming German family were all to become cheap labor, exploited by an unfeeling and greedy system. They would be tested in ugly tenements, suffocatingly hot in summer and freezing cold in winter, boxes without heat, hot water, or toilet facilities. The dream would expire in sweatshops at starvation wages or in dreary, endless toil in tenement homes. And the greatest of all crimes, the exploitation of children as laborers, would wither the hope and grace of the young.”

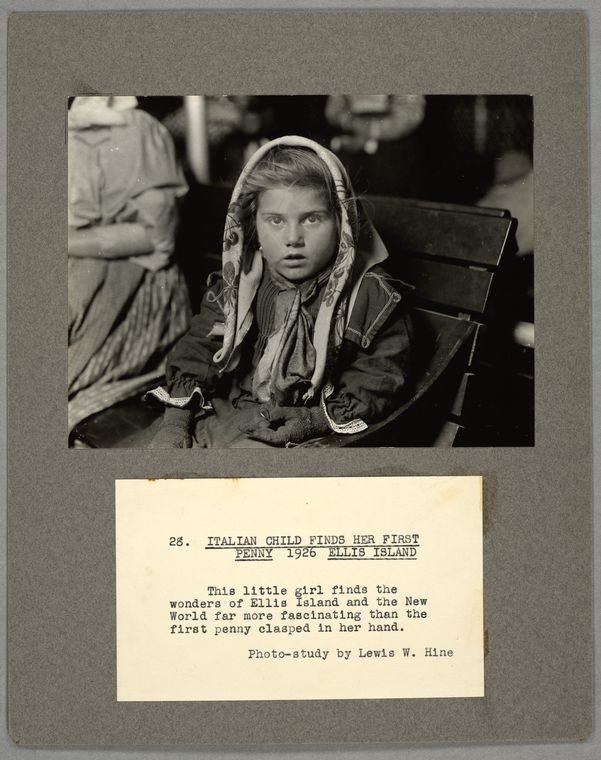

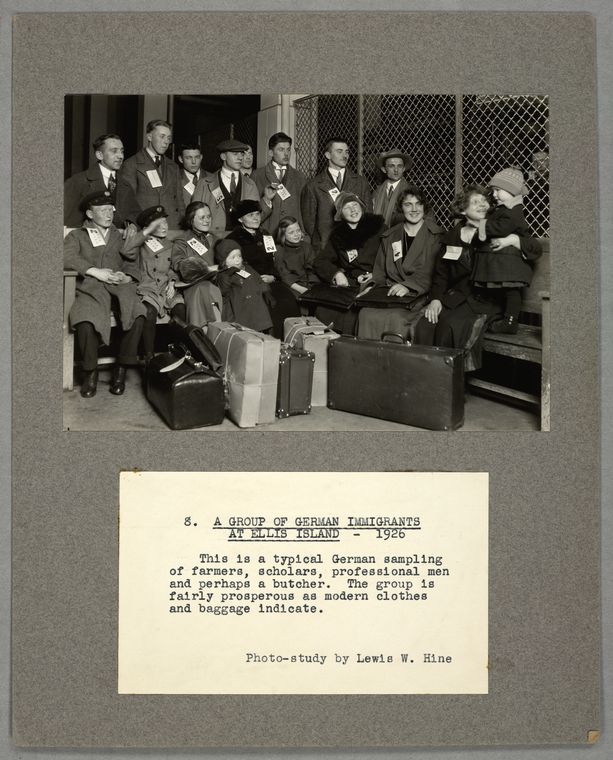

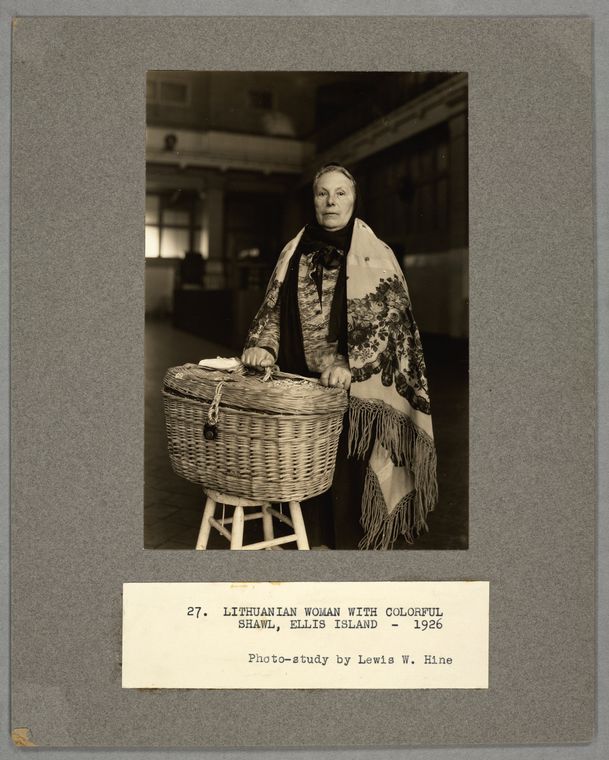

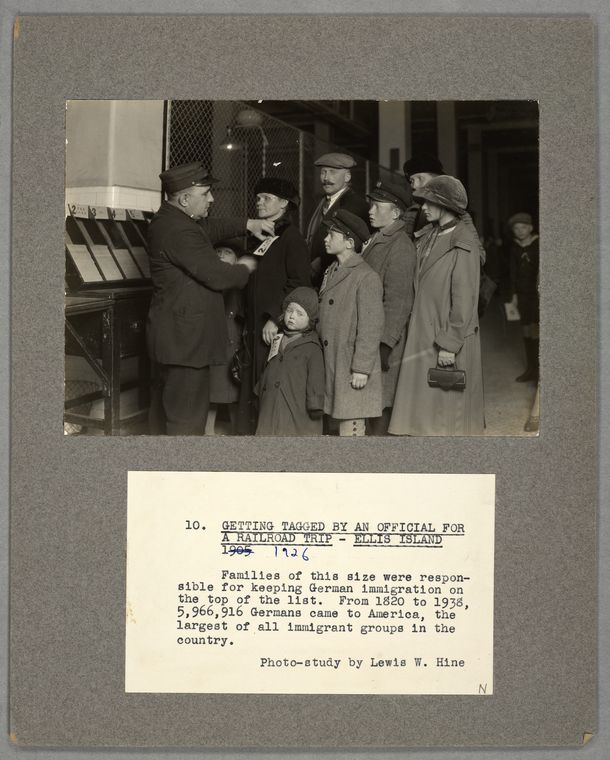

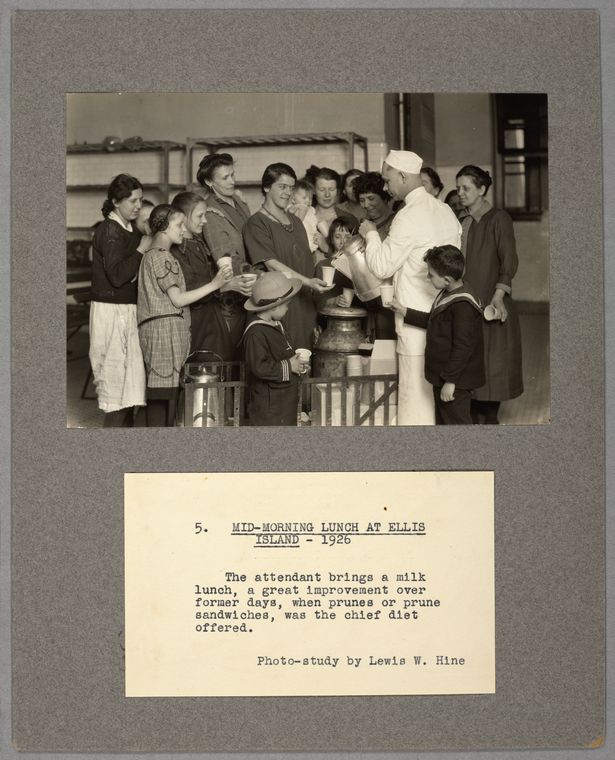

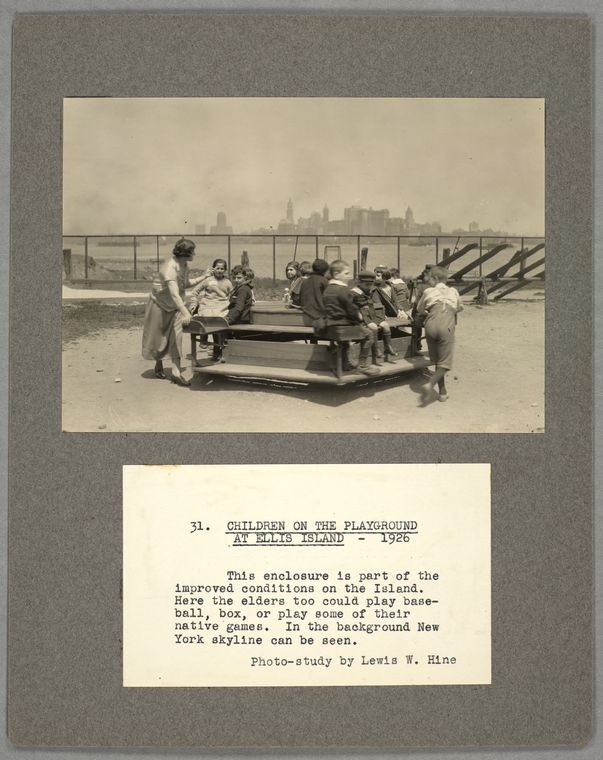

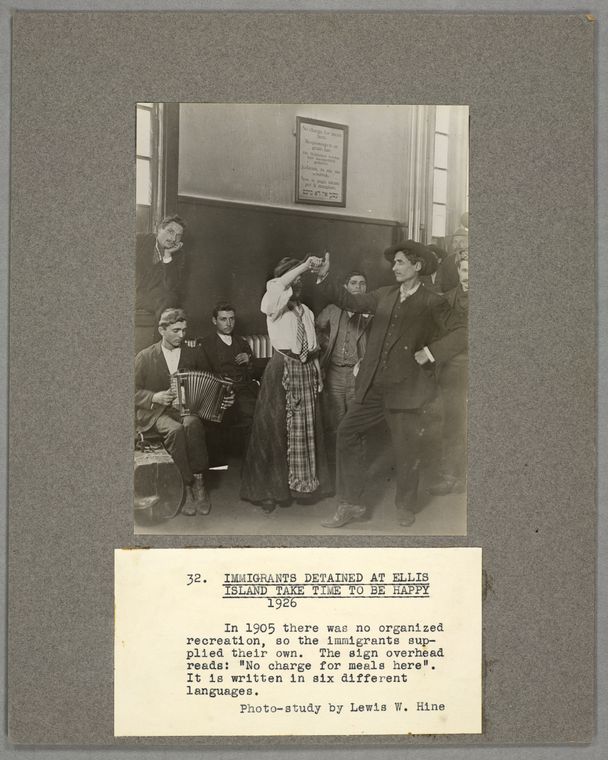

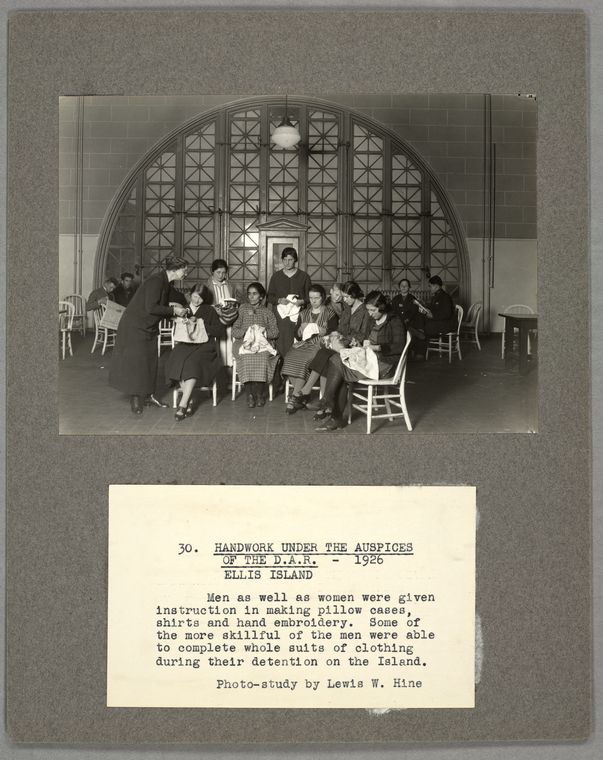

His typed captions for each photograph, mounted on dark grey board by Lewis himself, show such emotion, sympathy and interest for the individual’s story, rather than coldly labelling them with number tags like the immigration officers.

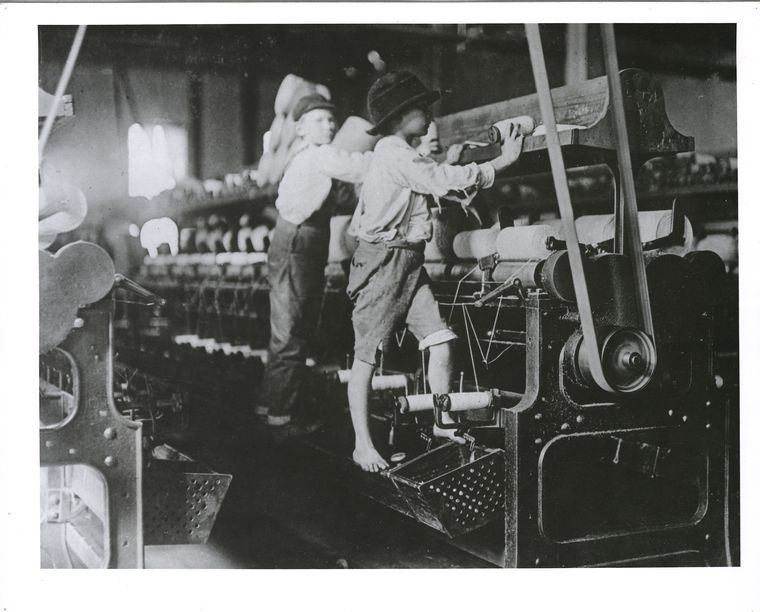

After nearly five years documenting the thousands of people that were churned and herded through Ellis Island everyday, it was only natural that Hine’s curiosity evolved and compelled him to document what came next for his subjects, once they left the island. He worked tirelessly, travelled great distances and often risked his own well-being to follow his interest in child welfare and the social conditions of the American industrial working class. While social injustice had been documented in England and Scotland in the late 19th century, Lewis Hine was the one of the first photographers in America to use photography as a weapon against immorality. He became immersed in the reform movement and his work was pivotal in the legislative battle against child labor.

“To gain entry into mines, mills, and factories, Hine was forced to assume many guises. His students at the Ethical Culture School had known him to be a marvelous actor who would amuse them on nature walks by becoming a wayward tramp or an itinerant peddler. When he photographed for the NCLC, his repertory ranged from fire inspector, post card vendor, and Bible salesman to broken-down schoolteacher selling insurance. Sometimes he was an industrial photographer making a record of factory machinery. He would set up to photograph a loom, then ask a child to step into the picture so that he could get a sense of scale. Hine knew the height from the floor of each button on his vest so that he could measure the child standing alongside him. Hidden in his pocket was a little notebook in which he wrote vital statistics such as age, working conditions, years of service, and schooling. When he failed to gain admittance to a factory, he would often visit homes in the early morning and wait outside to photograph the children on their way to a long day’s work.”

– Walter Rosenblum, America & Lewis Hine (1904-1940)

Click here to view a gallery of Lewis Hine’s later photographs concerning labor, housing and social conditions in the United States.

Despite his photography being pivotal in the rising social consciousness of his time, Lew Hine’s photographs would never be truly appreciated by his contemporaries as art. His photographs were rejected by LIFE magazine and even after his death, The Museum of Modern Art was offered his pictures but did not accept them. One of the world’s most famous photographs in American history, Lunch atop a Skyscraper, depicting eleven men eating lunch, seated on a girder with their feet dangling high above the New York City streets– may or may not have been taken by Lewis Hine. It was once credited to Hine, then credited to Charles C. Ebbetts and today officially holds the status as an anonymous work. Whether he took that particular photograph or not, Lewis Hine never sought after society’s awards and medals.

In the last years of his life, he struggled financially, lost his house and applied for welfare. He died in 1940 at the age of 66 when he was in the middle of putting together these very prints, mounted on grey card, as part of a definitive collection to be donated to a library.

Despite the lack of recognition of his artistry as a photographer, there were other ways Lewis had made an impression. He revisited Ellis island some twenty years later in 1926, to find that conditions had somewhat improved and that perhaps, his photographs had made a difference for the future.

This might be a good time to honour Lewis W. Hine for his work, his vision, for focusing his camera on the cracks and dark recesses of social turmoil. Pass these pictures around in the memory of Lewis Hine and the humans he photographed. We are in their debt.

Lewis Wickes Hine: Documentary Photographs 1905-1938 on the NYPL Digital Gallery