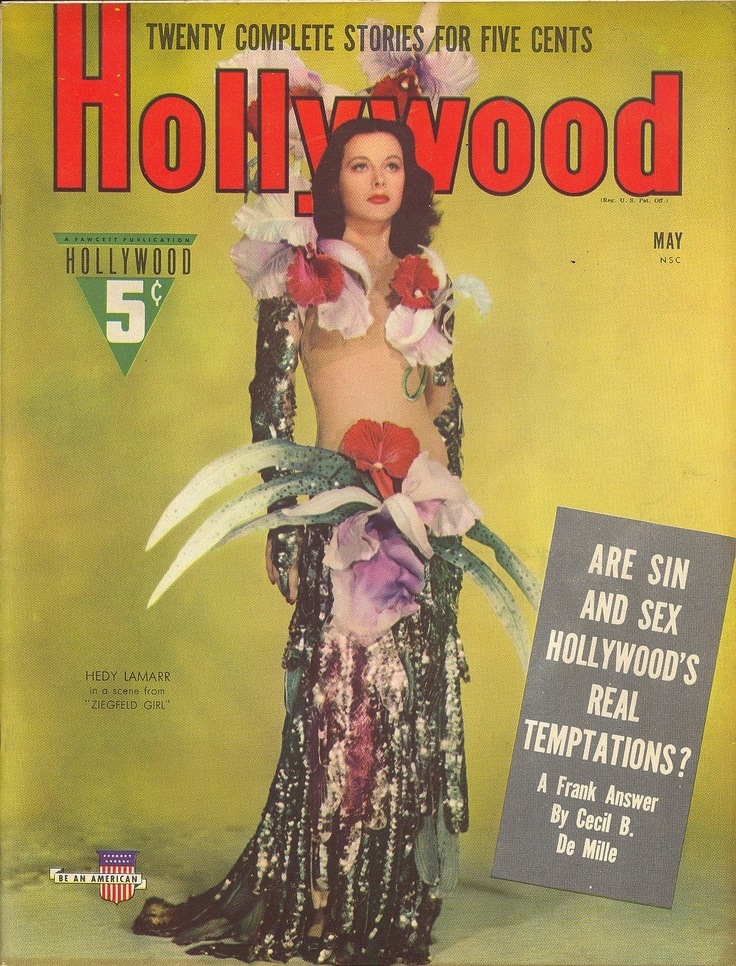

If this beautiful Hollywood starlet looks a little bored or unimpressed while posing in her rather ridiculous glitzy get-up, it’s because she probably was; her mind elsewhere– for instance, oh say … masterminding the breakthrough technology that would bring us the basis for modern-day WiFi and Bluetooth.

Hedy Lamarr was voted the most desirable pin-up girl during World War II, she was scandalously known as the first movie star to simulate a female orgasm on screen, but Hedy had a hidden intellectual talent and a blueprint for success that went far beyond Hollywood…

Her own story does play out a little bit like a Hollywood script however, and before we get into the details of exactly what she invented, the more burning question is inevitably going to be how this bombshell actress, surrounded by the superficial glitz and glamour of Hollywood, was able to nurture a secret talent in the scientific field.

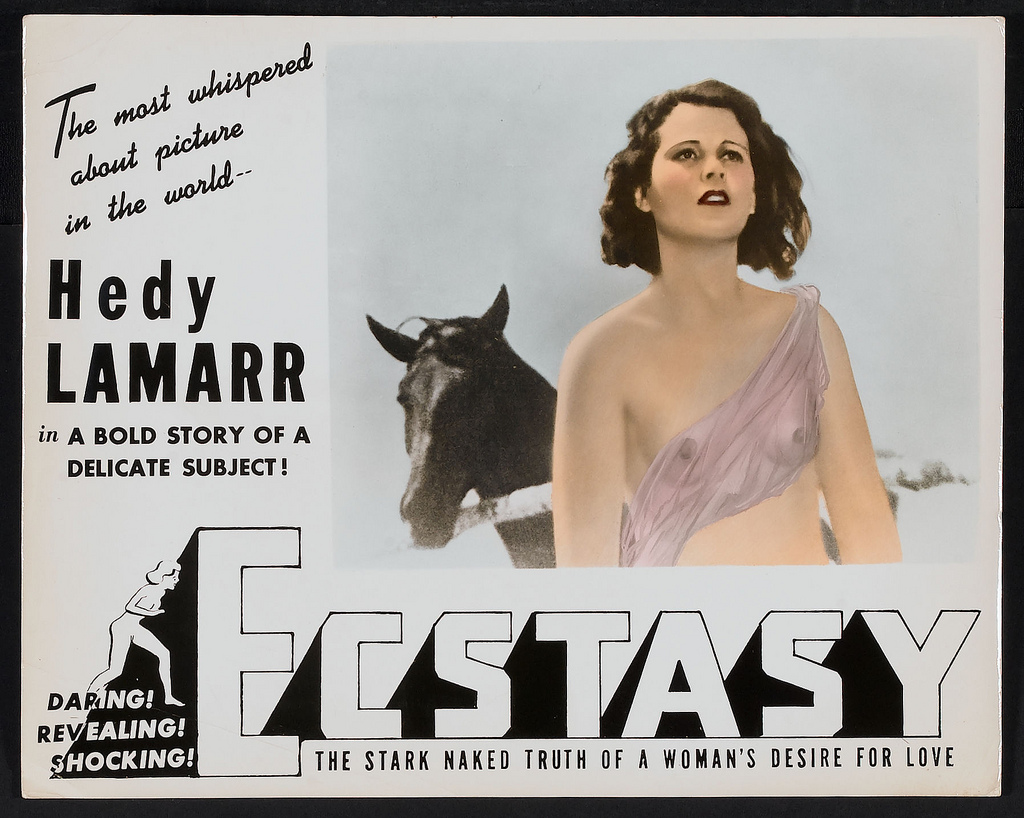

In 1933, at the ripe age of 18, Viennese-born Lamarr had just starred in Ectsasy, a highly controversial Czech romantic drama which was likely the first non-pornographic movie to portray sexual intercourse and the female orgasm. Hedy appeared nude in a scene where she goes skinny-dipping in the forest and the film became notorious for Lamarr’s face in the throes of orgasm. If you’re curious, you can see a clip of the scene here (around the 1:50 mark).

In the same year, Hedy also married Friedrich Mandl, a wealthy fascist arms manufacturer and the third richest man in Austria. According to Lamarr, both Mussolini and Hitler attended lavish parties which Mandl threw at their Austrian home, likely unaware that the beautiful hostess was born to a mother who came from the Jewish haute bourgeoisie in Budapest while her Ukranian father, a banker, was a secular Jew.

Mandl was an extremely controlling husband and didn’t want his young wife to pursue a career as an actress. He even attempted to buy up as many copies of Ecstasy as he could find in an attempt to restrict its public viewing. Instead, he had her accompany him to all his business meetings with scientists, high ranking officials and other professionals involved in military technology, where they chatted away about submarines, wire-guided torpedoes, and the multiple frequencies used to guide bombs. The usual. As Hedy sat quietly as the glamorous wife of an arms dealer who joked that she “didn’t know A from Z,” the brunette beauty took in every last detail.

With a dangerous war looming in Europe and her marriage becoming more unbearable by the day, Lamarr devised a plan to escape her husband and country. In her autobiography, Ecstasy and Me, Hedy describes how she disguised herself using the identity of her own maid to flee to Paris. In her last interaction with Mandl, she allegedly persuaded him to let her wear all of her jewellery for a dinner, and then she disappeared.

Hollywood-bound, Hedy went from Paris to London where she booked passage on the Normandie, a ship that she knew was also carrying movie mogul, Louis B. Mayer. Although Ecstasy had been banned in the United States, Mayer had seen it and was intrigued by the Austrian’s potential. By the end of the voyage, she had secured a $3,000-a-week contract with MGM providing she worked on her english accent. Hedy’s career quickly took off and soon enough, she was starring alongside the likes of Clark Gable, Spencer Tracy and Judy Garland. Her roles however, were rather unchallenging to say the least, invariably cast as the stereotypical exotic brunette and slightly sinful seductress. Hedy went looking for another escape and whilst playing the role of the Hollywood darling, she began secretly channeling her inner Thomas Edison.

In 1940, German U-Boats were wreaking havoc in the Atlantic, torpedoing ships with women and children aboard trying to flee the Nazis and the devastation of the Blitz. Lamarr was horrified but also believed there was something she could do about it. She set aside a room in her house with a drafting table, professional lighting, tools and a whole wall of engineering reference books. Using the secrets she had learned at her first husband’s business meetings, she began tinkering with the idea of a secret communication system that could guide a torpedo using technology called frequency hopping so that frequency couldn’t be intercepted. She kept her hobby private, hidden from the press and even her family, until she met another unlikely inventor at a chance dinner party.

George Antheil was an American avant-garde composer and pianist, but like Hedy, he also liked to tinker with ideas. A man of diverse interests and talents, he wrote magazine articles that accurately predicted the development and outcome of World War II and became a sought-after Hollywood film composer. During his earlier work in Paris, he had composed a symphony using self-playing pianos, a siren and three airplane propellers that were synchronised. The concert ended with a riot in the streets.

While George’s symphony might not have been well-received in cultural circles, Hedy was fascinated. Their chance Hollywood meeting raised the question: If pianos could be synched to hop from one note to another, why couldn’t radio frequencies that were steering a torpedo do the same?

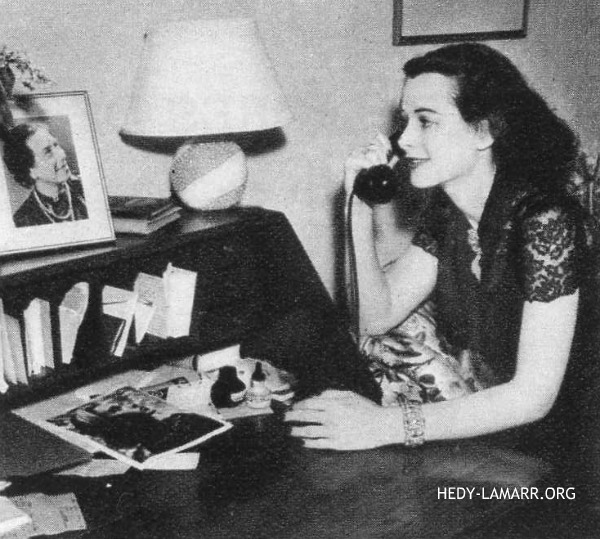

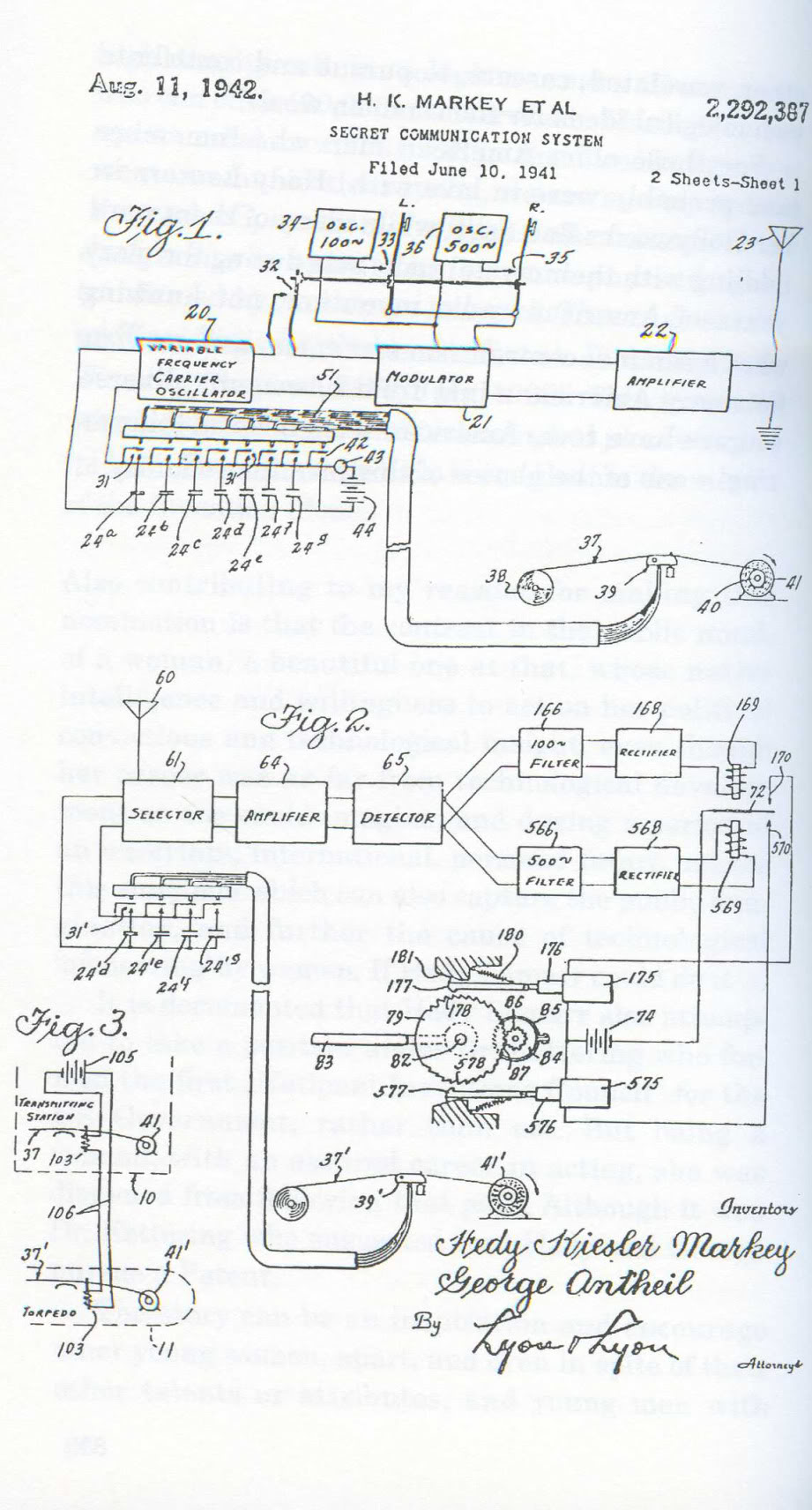

Together, they realised that if you could make both the transmitter and the receiver simultaneously jump from frequency to frequency then someone trying to jam the signal (the Nazis), wouldn’t know where it was. Hedy had the idea for a radio that hopped frequencies and Antheil had the idea of achieving this with a coded ribbon, similar to a self-playing piano strip. A year of phone calls, drawings on envelopes, and fiddling with models on Hedy’s living room floor produced a patent for a radio system that was virtually jam-proof, constantly skipping signals.

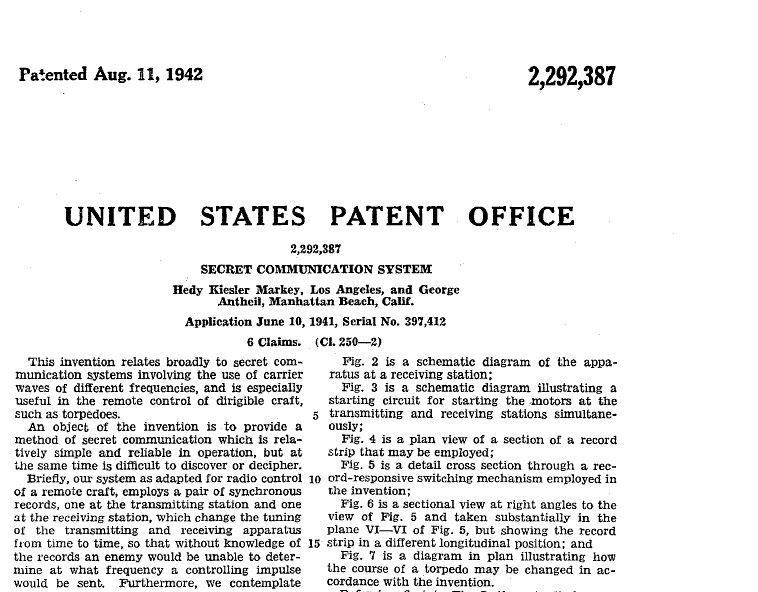

On August 11, 1942, U.S. Patent 2,292,387 was granted to Antheil and Hedy Kiesler Markey, Lamarr’s married name at the time.

‘You want to put a self-playing piano in a torpedo?’ was more or less the Navy’s response to Hedy’s breakthrough discovery, suggesting she would be better off using her celebrity and her looks to sell war bonds. She signed the patent over to the Navy anyway and left it at that. Her idea was not implemented in the United States until 1962 during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Today, Lamarr’s technique of frequency hopping (commonly known as spread spectrum) is now widely used in telecommunications, from the wireless phones in our homes, to GPS and most military communications. Hedy Lamarr never made a dime off it.

More than 50 years after she registered the patent, Hedy began to receive acknowledgement for her invention and even got some awards, but she never showed up to accept them. Her movie career had begun to go downhill in the 1950s and she became increasingly reclusive until she died alone in Florida at the age of 86.

Her obituary only made fleeting references to her inventive side, more interested in recalling her beautiful face than her beautiful mind.

So for all you Hedy Lamarr’s out there– don’t hide in the shadows. Step out of your comfort zone, take a leap and be the first. For more information about Vodafone Firsts program, and to submit yours, go to www.firsts.com