His lifework documenting the North American native was once hailed as “the most ambitious enterprise in publishing since the production of the King James Bible.” Today I found his photographs deep in the Flickr’s archives. At the height of Edward Curtis’s career, he had one of the most powerful bankers of his era, J.P. Morgan, personally financing him. But much like the subjects Curtis chose in his photographs, he and his work seem to have been tragically forgotten in the past…

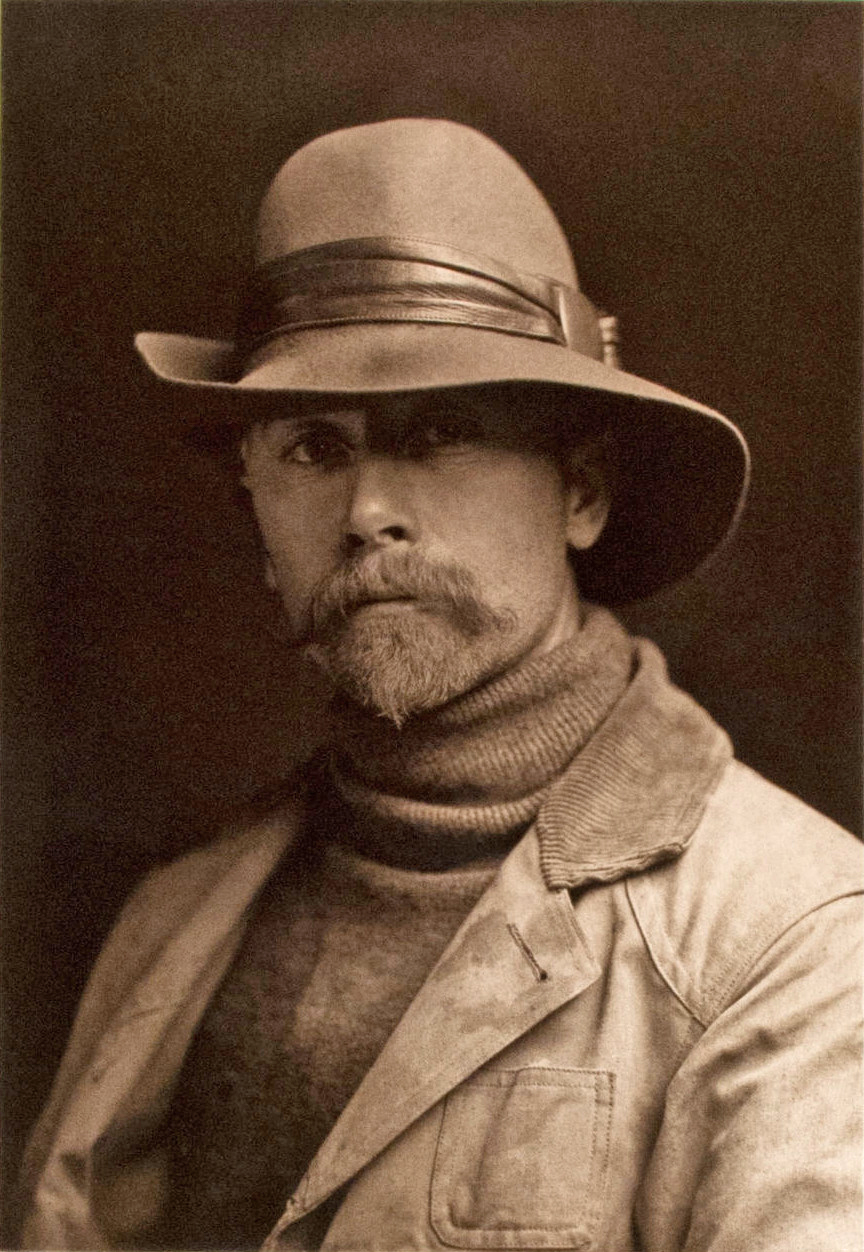

Pictured in his self-portrait above, Curtis started up with photography at a young age, taking apprenticeships and eventually purchasing his own share in a photography studio in Seattle, where he settled with his young wife and their expanding family. He made a good living taking flattering photographs of society ladies, but soon enough, the call would come.

A born adventurer, Curtis befriended a group of prominent scientists who invited him on his first quest as the official photographer for an expedition to Alaska in 1899, a two month journey discovering remote Eskimo settlements and glaciers. You could say Edward instantly caught the travel bug.

When the scientists invited him to come on a visit to the Piegan Blackfeet in Montana the following year, he packed his camera, months worth of supplies and left his young family again to travel by foot and by horse deep into the native territories. Curtis was instantly taken with the North American tribes and their way of life. It was an encounter that would change the course of his life.

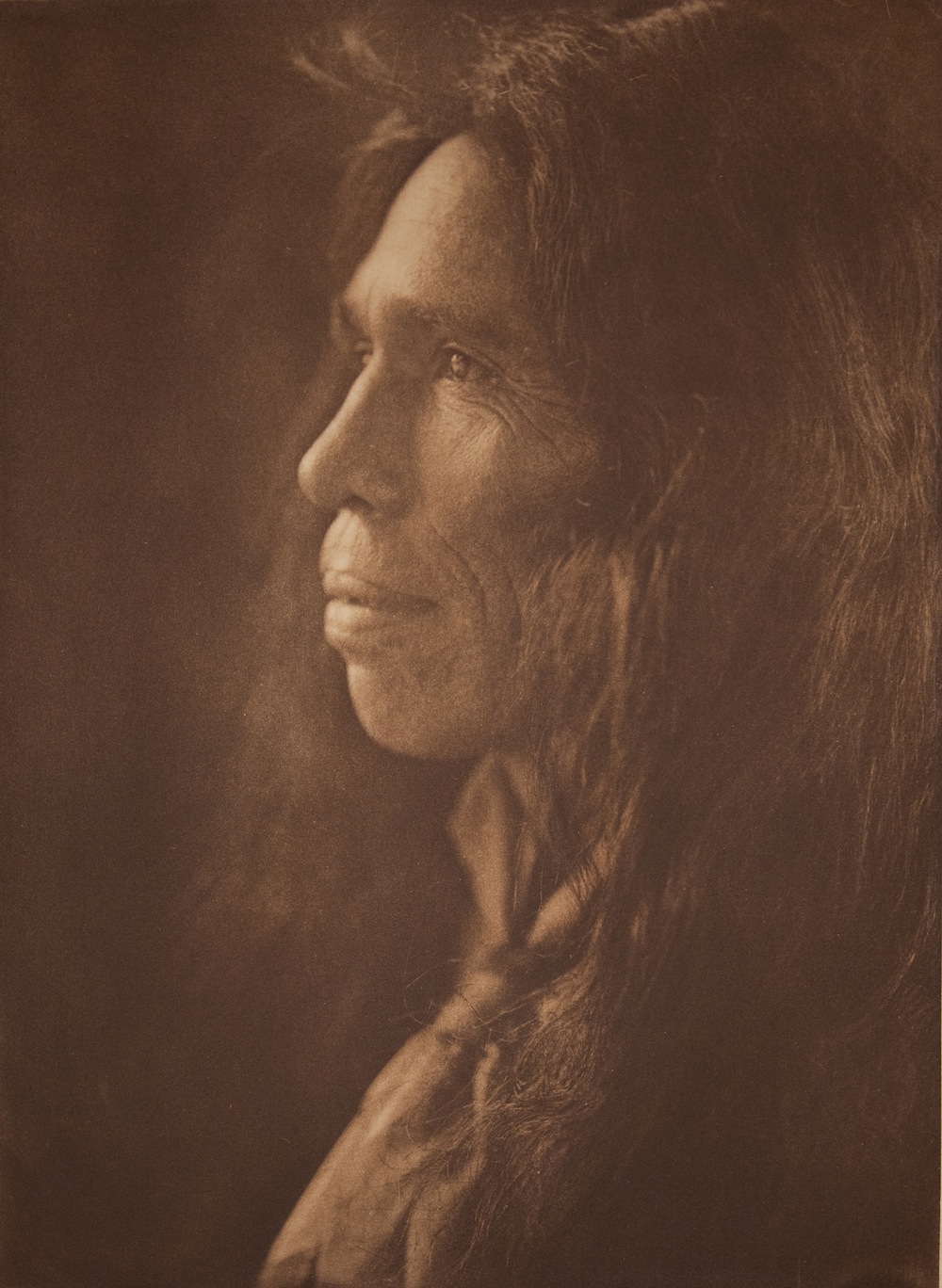

When he returned from his first trip, his Native American photographs quickly became known for their striking beauty, shot with his oversized view camera which produced glass-plate negatives that came out with sharp and gorgeous gold-tone prints. His work enjoyed popular exhibitions, notable magazines published him and he lectured across the country about his finds.

But he yearned to go back and photograph more, learn more and record more before the federal government destroyed what remained of the natives’ way of life. Sensing he had very little time left, in 1906, he approached J.P Morgan, one of the wealthiest financiers in the world. Amazingly, after some persistence, Curtis managed to get Morgan’s eyes on his work, which quickly did all the talking. In response to the ambitious photographer’s request, Morgan replied, “Mr. Curtis. I want to see these photographs in books—the most beautiful set of books ever published.”

The agreement saw to it that Morgan would sponsor Curtis over five years in exchange for 25 sets of volumes and 500 original prints. It is estimated that producing Curtis’ masterwork The North American Indian today would cost more than $35 million.

Curtis traveled with researchers, assistants and interpreters who traveled ahead of the group’s trail wagon to arrange visits. The journey itself was long and perilous and Curtis describes some dangerous encounters with “unfriendly warriors” in his works. But when it came to the people he stayed with, Curtis was good at making friends and they came to trust him. Describing his way of photographing them, he said, “We, not you. In other words, I worked with them, not at them.”

The Native Americans came to call Curtis, “Shadow Catcher”. He documented more than 80 tribes , collecting 10,000 recordings of songs, music and native speech. The tribes even obliged (sometimes for a small fee) to reenact traditional ceremonies and battle calls among the natives for Curtis to capture with his 14-inch by 17-inch view camera.

But the truth is, by this time, Native American culture had already been penetrated by American colonial expansion. Many of the tribes Curtis visited had already been “influenced” by the government; their children forcibly sent to boarding schools, their native tongue banned and their traditions forbidden. Curtis found it hard to accept this and preferred his images to represent a timeless, untainted vision of Native American culture, choosing only to photograph people in traditional clothing and surroundings, even going as far as retouching his photographs if they contained any giveaways of modern outsider influence.

In 1913, Curtis’ unlikely financier, J.P. Morgan died suddenly. The banker’s son significantly cut sponsorship which soon forced Curtis to abandon his work. During the years he had been away, the photographer’s absence has taken on toll on his family life and several years after his funding dried up, his wife Clara filed for divorce. She was awarded his studio and the family home but Curtis made sure she wouldn’t get his work. Together with his daughter, he made copies of some of his glass plate negatives and then destroyed the originals.

But Curtis was already a ruined man. In a last-ditch attempt, he had tried to make a motion picture for Hollywood, but the film flopped, along with his $75,000 investment. The American Museum of Natural History bought the rights to the movie for $1,500. He then tried to strike a deal with the Morgan Company that saw him give up all his copyrights on the images for The North American Indian in exchange for some minimal funding to return to his field work.

But it was too late, the traditional tribal life he had visited in his earlier career had disappeared.

They had already become part of a different world, adopted to the ways of another culture and Curtis could not longer create those raw images of an untainted people. Possibly even more alarming, the public’s interest in Native American culture had faded.

Curtis was never able to sell any of his work again. His ex-wife had him arrested for failing to pay alimony and child support as the Great Depression dawned on the country. He was hospitalised after suffering a mental and physical breakdown while the Morgan Company sold off most of his life’s work for $1,000 (and a share of any future royalties).

In 1952, his small obituary in the New York Times simply read:

“Mr. Curtis devoted his life to compiling Indian history. His research was done under the patronage of the late financier, J. Pierpont Morgan… Mr. Curtis was also widely known as a photographer.”

The remaining material bought by a Boston publisher, remained untouched in their basement until the prints were rediscovered in 1972. There was a brief revival of interest in his work, some of which fetched high prices at auction, indicating an increased sense of awareness of Native American issues at the time.

But still, I don’t think these photographs and their subjects are being remembered enough. I can’t even begin to pretend to talk about the injustice the Native American people have faced. But I think in reminding ourselves what has been lost, words aren’t always needed.

Photographs digitally available thanks to the Museum of Photographic Arts Collections.