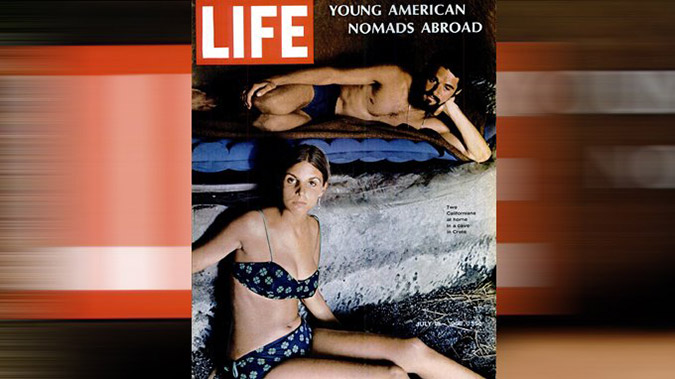

In a sleepy fishing village on the island of Crete, where Joni Mitchell had found herself a nomadic home inside manmade Neolithic caves carved into the sandstone cliff, she sang her folk songs, “under a starry dome…beneath the Matala Moon.”

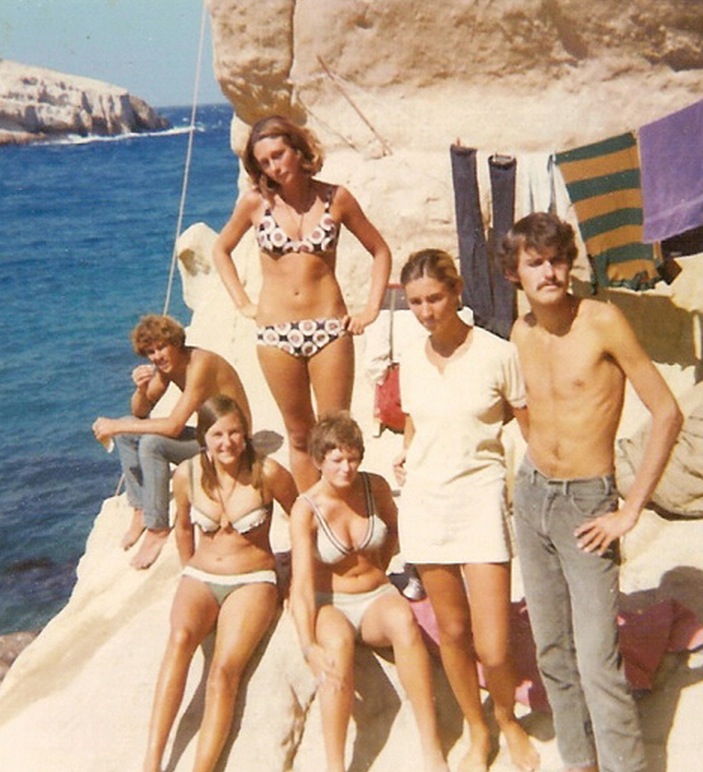

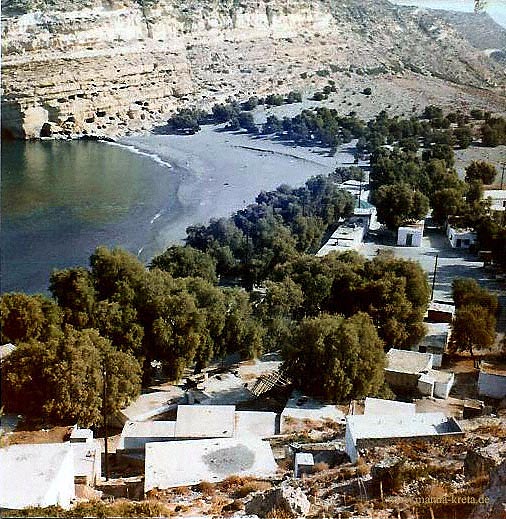

It was the 1960s and a community of backpacking hippies had settled in Matala, a remote corner of the Mediterranean island where most locals had never seen a tourist before their arrival. It was here that Joni immortalised the ideal hippie scene in her 1971 song “Carey”, overlooking the unspoilt beach and azure blue waters.

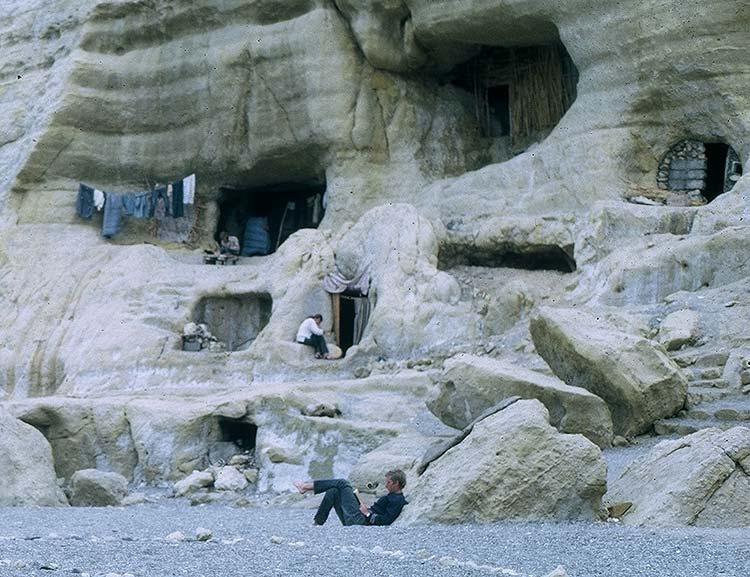

The caves had originally housed lepers at the end of the Stone Age and then the Romans used them as burial crypts. When the hippies arrived searching for peace and enlightenment, the caves became the cheapest hotel in town. But of course, there was no hotel in town anyway.

There were no homes in Matala, “just two grocery stores, a bakery where the owner made fresh yogurt and bread, a general store with the only phone in town, two cafes and a few rental huts,” remembers Joni in an interview. “I don’t know what their business was before people came.”

Life was simple in Matala, perhaps too simple because the hippie nomads were eventually driven out by the church and the military junta.

In an interview given from her home in Los Angeles at the age of 71, Joni recalls the story of how she ended up in Matala following a painful break-up from her then-boyfriend, British singer/ songwriter Graham Nash…

In Greece, Penelope and I spent the first few days in Athens. I didn’t think I looked like a hippie, but I definitely didn’t look Greek. My fair hair made me stand out … my hair seemed to offend people, mostly men, who called out with a big grin on their faces, ‘Sheepy, sheepy, Matala, Matala.’ I asked around about the phrase and was told it meant, ‘Hippie, hippie, go to Matala in Crete. That’s where your kind are.’

A few days later, Penelope and I were on a ferry to see what Matala was all about … Most of the hippies who had traveled there slept in small caves carved into the cliff on one side of the beach.

After we arrived, Penelope and I rented a cinder-block hut in a nearby poppy field and walked down to the beach. As we stood staring out, an explosion went off behind us. I turned around just in time to see this guy with a red beard blowing through the door of a cafe. He was wearing a white turban, white Nehru shirt and white cotton pants. I said to Penelope, ‘What an entrance—I have to meet this guy.’ … He was American and a cook at one of the cafes. Apparently, when he had lit the stove, it blew him out the door. That’s how Cary [Raditz] entered my life—ka-boom.

Carey, of course is the man behind the well-known song, “Carey”, that appeared on one of Joni’s most critically acclaimed albums, “Blue” in 1971. Have a listen to it here…

Some of the lyrics from the song…

The wind is in from Africa

Last night I couldn’t sleep

Oh, you know it sure is hard to leave here Carey

But it’s really not my home

My fingernails are filthy, I got beach tar on my feet

And I miss my clean white linen and my fancy French cologne

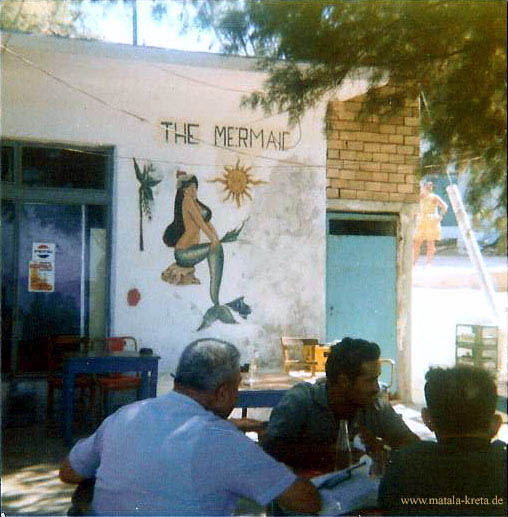

Come on down to the Mermaid Cafe and I will buy you a bottle of wine

And we’ll laugh and toast to nothing and smash our empty glasses down

Let’s have another round for the bright red devil

Who keeps me in this tourist town

The night is a starry dome.

And they’re playin’ that scratchy rock and roll

Beneath the Matalla Moon

The Mermaid Cafe mentioned in the song was a real establishment, owned and operated by local Stelios Xagorarakis. In 1969, he was arrested for an “illegal addition on his kitchen,” and thrown in jail by the Junta. His hands and feet were burned with cigarette butts by the military colonels (torture was legal there at the time). Stelios later followed his hippie customers and settled in Southern California.

Joni described one of her first nights at the Mermaid Café upon arriving in Matala and meeting Carey…

The next night, Penelope and I went to the Mermaid Café for a drink with Cary. Several hippies were there along with some soldiers. Someone recommended this clear Turkish liquor called raki. I wasn’t a big drinker, and after three glasses I woke up the next morning alone in Cary’s cave.

The stacked leather heels of my city boots had broken off, apparently from climbing a mountain the night before. I had no recollection of the climb. Later, when I returned to my hut, Penelope was gone. I was told she went off with one of the soldiers from the Mermaid the night before. That was the last I saw of her for many years.

Mitchell moved into the caves with Carey, beginning a relationship with him.

With Penelope gone, I was alone—and vulnerable. You have to understand the fragile emotional state I was in. I was still in pain and had no one to talk to. Also, I had a bit of fame by then, and wherever I’d go, hippies would follow. I latched myself on to Cary because he was fierce and kept the crowd off my back.

Comfort in the caves was minimal. In the 50s, when the hippies first began settling the caves, they dug out more rooms but sleeping there was rough and the only thing they had to soften the surface were beach pebbles places on a stone slab, covered with beach grass.

“I borrowed a scratchy afghan blanket and placed it on top,” remembered Joni. “When the waves were high and crashed on the beach, they shook the stone in the caves.”

We can tell when Joni wrote the lyrics to “Carey” that she was already starting to miss the comforts of home and on the eve of a departure.

Oh, you know it sure is hard to leave here Carey

But it’s really not my home

My fingernails are filthy, I got beach tar on my feet

And I miss my clean white linen and my fancy French cologne

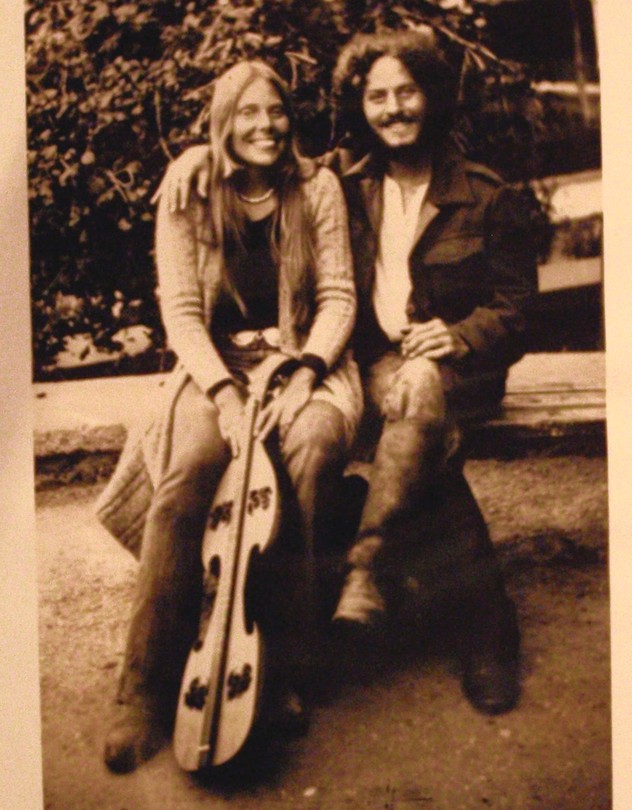

Jon pictured with Cary Raditz in Matala, the ‘e’ in ‘Carey’ was a mispelling of his name on her part.

She wrote her songs on her dulcimer, smaller than a guitar and took it everywhere with her around Matala and the island, trying to find solitude away from her hippie groupies. She wrote the song ‘Cary’ named after her island boyfriend for his birthday.

My lyric, ‘Oh Carey get out your cane‘ referred to a cane Cary carried with him all the time. He was a bit of a scene-stealer, and the cane was a theatrical prop for him … When I played the song for Cary on his birthday, I don’t recall his reaction. He was always detached and sometimes even disrespectful—either trying to belittle me or make me feel afraid. I think at the time he felt greatly superior to women, which is why I refer to him in the lyrics as ‘a mean old Daddy.’

In the Spring, Cary and Joni travelled to Athens to see some of their hippie friends who had been cast in a Greek theatrical production of “Hair”. But Joni would not return to Matala. She had had enough and it was the end of her story there.

“My hair was matted from washing it in seawater for months, I had beach tar on my feet and I was flea-bitten—this was very rugged living. I also realized I was still heartbroken about my split with Graham.”

Before a gig at the Troubadour in Los Angeles in 1971, where she performed “Carey”, Joni spoke to the Rolling Stones magazine about Matala.

“The cops came and kicked everyone out of the caves, but it was getting a little crazy there. Everybody was getting a little crazy there. Everybody was getting more and more into open nudity. They were really going back to the caveman. They were wearing little loincloths.”

Some of the hippies began making ‘Roman art’ and necklaces out of human teeth (don’t forget the caves had also been Roman crypts at a time).

“The Greeks couldn’t understand what was happening,” said Joni.

Today, Matala is a small village still living mainly from tourism and while the caves where the hippies lived (now fenced-off) can be visited, they are protected by the Archaeological Service, and certainly nobody is allowed to live or spend the night in them. The true nomadic hippie culture no longer exists in Matala, but there are hints to its bohemian past and a few people have tried to continue the lifestyle in Crete, on Disko beach in Lendas.

As for Cary?

“I haven’t spoken to Cary in years,” recalled Joni, decades after their island affair. “We remained friends, he married and we lost contact. But every so often Matala comes back into my life. A couple of years ago, a friend sent me a newspaper article about Matala. It has been built up a bit, and there’s an annual musical festival held there now. The article said that in Matala I’m more popular than Zeus. I thought that was funny, you know?”