If you were to take photographs of the most charming villages from around the world and make a collage of their most picture-perfect views, you’d get a pretty good representation of what Portmeirion looks like. An enchanted technicolor mish mash of architecture, built in the 1920s by one wizard of a man, let’s take a trip down Britain’s own unexpected yellow brick road leading to the edge of Snowdonia…

This is not a Disneyland attraction you’ve never heard of but a real village in Wales that earned itself a reputation as a “home to fallen buildings”, where unwanted architecture found an after-life in an unlikely paradise. Its founder, Sir Clough Williams-Ellis, was a self-taught architect who rebelled against the Brutalist style and functional concrete that was taking over the urban and rural landscapes of 20th century Britain. After the world wars, a harrowing amount of Britain’s architectural heritage was in line for the wrecking ball to make way for a vision of modernist architecture, but Williams-Ellis took it upon himself to acquire these unwanted buildings and rescue them from demolition.

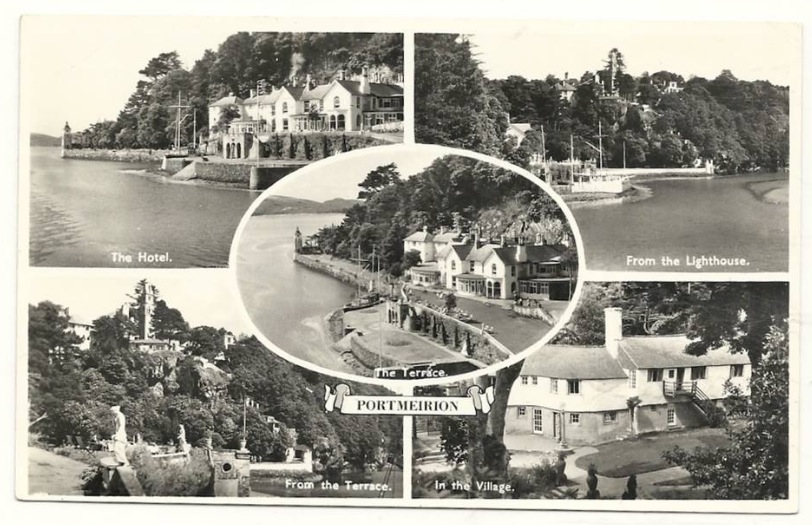

In 1925, Sir Clough acquired a small derelict Victorian estate on a sandy estuary beneath Snowdonia and transported his rescued pieces of architecture there to begin building a storybook village he named Portmeirion. He built his town hall from the salvaged pieces of a condemned 700 year-old mansion in North Wales awaiting demolition. Clough bought the 17th century barrel-vauled Jacobean ceiling from the mansion’s ballroom for $13 at auction, sawed it into a hundred pieces and packed it in straw crates back to Portmeirion, along with a fireplace and mullioned windows. Other rescued architectural features in Clough’s fantasy village that would otherwise have been lost, include two 18th-century neo-Classical bathhouse colonnades, a Gothic gatehouse, Baroque houses, a Chinese pagoda and white-washed Cotswoldian cottages.

There are also smaller salvaged details like the 19th-century metal railings with filigree mermaids from a seamen’s home, an antique statue of St Peter and the even the town’s observatory tower has a camera obscura that was rescued from a German U-boat. No building is like the other and every inch of Portmeirion has its own story.

Until his death, the visionary continued embelleshing and building the village for 50 years with found and rescued architecture, earning himself a name for his own architectural technique, dubbed the “Cloughed-up” style.

Inspired by the prettiest towns in Europe, he had developed an early passion for Italian architecture after travelling to the seaside resort of Portofino. So to add a touch of Italy to his canvas, Clough also added a central piazza to Portmeirion, complete with sub-tropical gardens and a domed Pantheon perched on the hillside.

On one street you can feel as if you’re on a Mediterranean island and turn the corner to be transported to a historic Dutch or Norweigan village. Its chameleonesque ability to resemble another place and time even saw Portmeirion lend its streets to the movie industry as a backdrop for films set in France (Brideshead Revisited), 1960s Italy (The Green Helmet), Renaissance Italy (Dr. Who) and even China (Danger Man). The exteriors for the cult 1960s series, The Prisoner were also primarily filmed in Portmeirion.

Williams-Ellis had intended his village to inspire great artists, even building special art studios intended for specific painters to take up residence in. But the artists never came. One BBC journalist suggests it was perhaps ironically because Portmeirion was already a work of art itself. But although the artists stayed away, royalty did not. Edward Prince of Wales was charmed by Portmeirion, so much so that when he visited in 1943, he had Williams-Ellis temporarily increase the village’s entrance fee to £1 so he could enjoy it in peace with as little visitors sharing the streets.

Sir Clough continued this tradition of sporadically raising the price of a day pass at any given time, just to keep the village getting too crowded for both his residents and visitors. But the architect had always intended Portmeirion to be a tourist destination.

One of the first things Sir Clough had done when he began building Portmeirion was open a hotel. Then he bought another hotel on the road from London to accommodate day-trippers as a halfway house.

Nearly forty years after Sir Clough’s death, his own descendants are now running Portmeirion as a charitable trust and continue to complete their grandfather’s last unfinished projects. In 2012, a music and arts festival was launched in the village and a literary festival is expected to be held in the coming summers.

The whole village is a Grade II landmarked site.

An opera of architecture, Portmeirion exudes the magic of a place you could only find at the end of the yellow brick road. And returning to the real world after visiting? You might just have to click your red shoes and repeat three times: “There’s no place like home”. But would you really ever want to leave Munchkinland?

If you’d like to add this place to your bucket list, visitors can choose from two hotels (one contemporary chic and the other antique original hotel), there are apartments within the village cottages and one self-catering cottage. You can find all the information you need on Portmeirion here.