Social media may be the poster child of the 21st century, but the ideas behind LinkedIn and Facebook go back a long, long way.

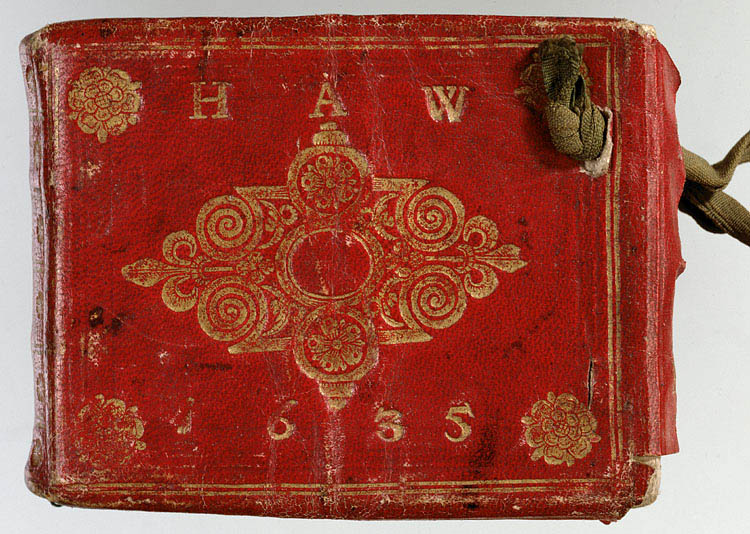

Dutch PhD scholar Sophie Reinders is currently exploring how personal books from many centuries ago known as alba amicorum – Latin for “friend books” – functioned as a sort of pre-dated version of our modern social media. So let’s take a look and compare, shall we?

(Be prepared for some major art-envy by the way, because all these lavish portraits beat selfies any time…)

According to Sophie, alba amicorum were used to establish and solidify personal and professional relationships of Northern European youngsters of nobility as early as 1560. They were also used to share favorite songs, reveal crushes, offer advice, share opinions, and offer comments on other people’s entries – sound familiar?

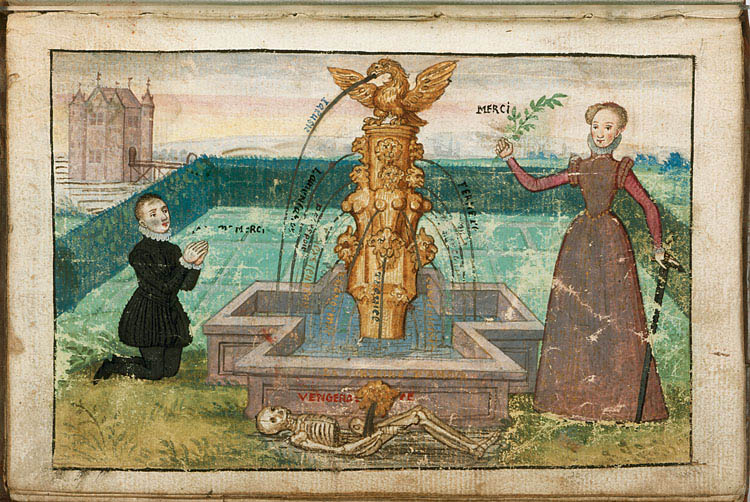

A little love-post – or a relationship update?

And like Facebook, it all started at university.

In the 16th century, young Dutch, German and French noblemen would go on a foundational version of a Euro-tour in order to educate themselves about the world and visit the times’ most influential cities, universities and educators.

To record the professional networks they built during these tours, boys would carry a book with them in which they’d have scholars, philosophers, scientists, artists and fellow students write up a short entry, generally recalling their pleasant meeting and faith in the young men’s ventures into the professional world.

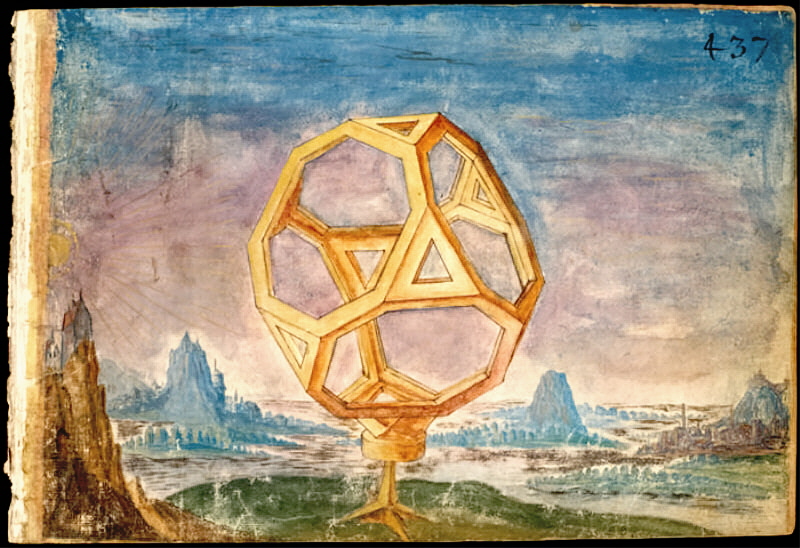

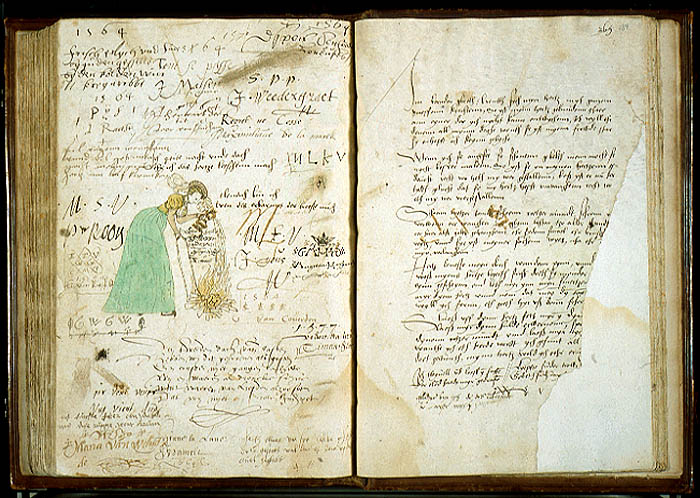

To get an idea, take a look at the very impressive album of Michael van der Meer (1590-1653):

Even the King of England makes an appearance! (That’d be a nice LinkedIn connection…)

A full book would underline the boys’ social standing and heighten their chances in the professional world – much like a strong LinkedIn network today.

Pictures of a pretty lady were not uncommon!

Boys’ alba amicorum often look very appealing, as famous artists would be requested to paint the men’s family weapons or lavish pictures symbolizing the well wishes they had for the young men and the adventures they embarked upon. (What I wouldn’t give to have my LinkedIn-profile picture custom made by Banksy…)

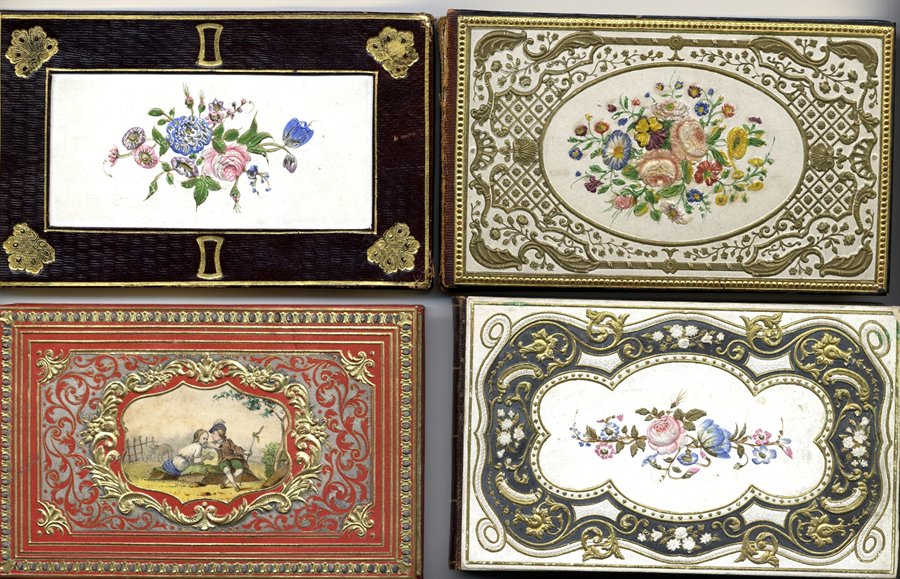

Unfortunately, girls rarely had access to famous artists. But that doesn’t mean that their versions of the friendship books were not as – if not even more – interesting.

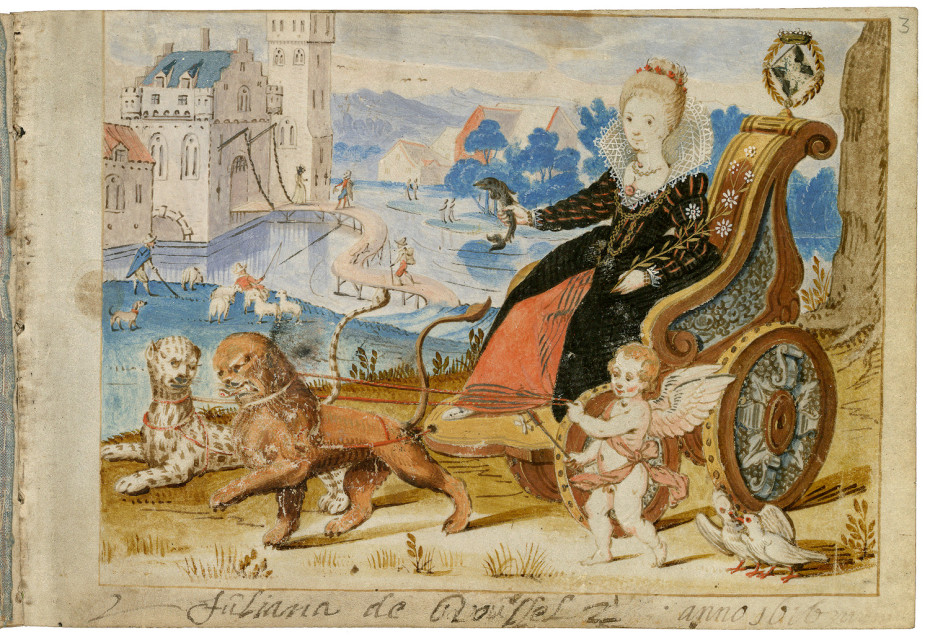

One of the few lavishly decorated women’s alba – Juliana de Roussel

Girls then didn’t have the freedom to travel the world – instead they were sent to convents or courts as a lady-in-waiting to receive their formative training as young women of high social standing. But that didn’t keep them from taking a page from the boys’ books (pun intended) and creating their own alba.

Album Amicorum of Jacoba Cornelia Bolten (1787-1859)

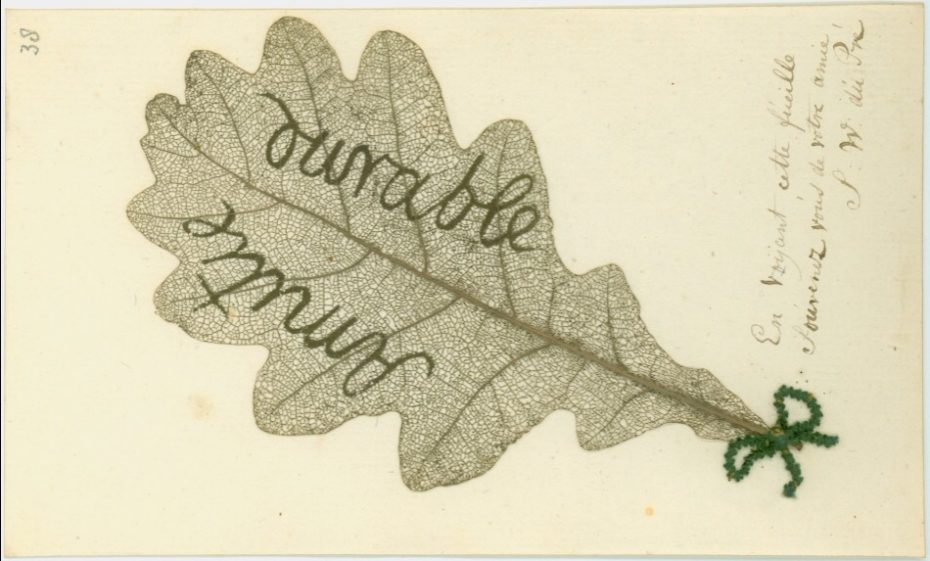

According to Sophie, girls’ alba amicorum were much more like Facebook than LinkedIn – as they were used to establish and solidify friendships, exchange gossip, and are riddled with inside jokes, personal advice, entry-comments, and illusive hints to secret romances.

Friendship book of Petronella Moens

So how do these books compare to modern-day Facebook? Instead of sharing pictures or videos, they would draw them. Instead of sharing an opinion or newspaper article, they would share a piece of advice or biblical passage, and instead of sharing their favorite song or Spotify playlist, they would write down the lyrics to their favorite song (of course writing a cliché love song in someone’s book was the perfect hint that you were digging that person). You could also impress by jotting down some personal poetry, showing off your languages, or getting a little artsy. And relationship updates were done by posting together after marriage.

An attempt to win the book’s owner’s heart with a picture of Tobias and the angel Rafaël – by Frans van Jongema

There were also entries that mirror Facebook “event pages,” where guests and friends would write their personal recollections of private parties.

Event page from Margaretha Haghen’s album

The album of Margaretha Haghen for example, includes this little (freely translated) gem:

“In Shrovetide, on day two,

We guests wrote this for you

And could not leave for home,

So tipsy we’d become;

Love made us so besotted

We left nothing in the bottle.”

The more people wrote in your book, the better you could show the rest of the world that you were a social and popular young lady. And by looking at who wrote what in whose album, Sophie now reconstructs social networks, friendships, acquaintances, and social exchanges from over 400 years ago.

Anyone else now craving an app that converts your Facebook page to an Amicorum style version?

If you’d like to learn more about Sophie’s research, you can visit her (Dutch) website here.

Inge Oosterhoff is a Dutch graduate of North American Studies, currently living in the Netherlands. With a love for the odd and the unexpected she is on a never-ending search for new stories, new people and the very best coffee in the world.

Inge Oosterhoff is a Dutch graduate of North American Studies, currently living in the Netherlands. With a love for the odd and the unexpected she is on a never-ending search for new stories, new people and the very best coffee in the world.