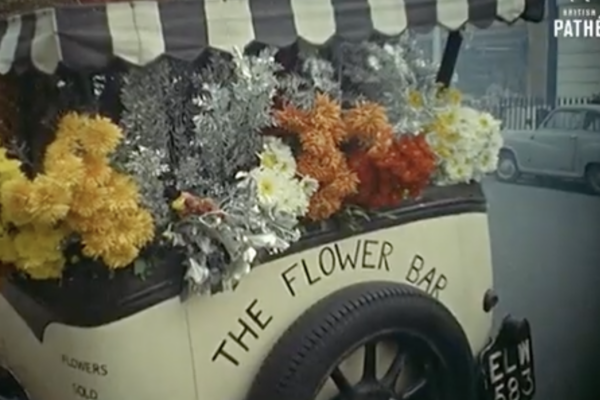

Have you ever seen a strangely misshapen tomato growing in your vegetable garden? A uniquely pigmented plant in your backyard that’s just not like others, able to thrive even in the harshest of seasons? There’s a very good chance that it could be an atomic heirloom from a forgotten atomic garden of the 1950s and 60s.

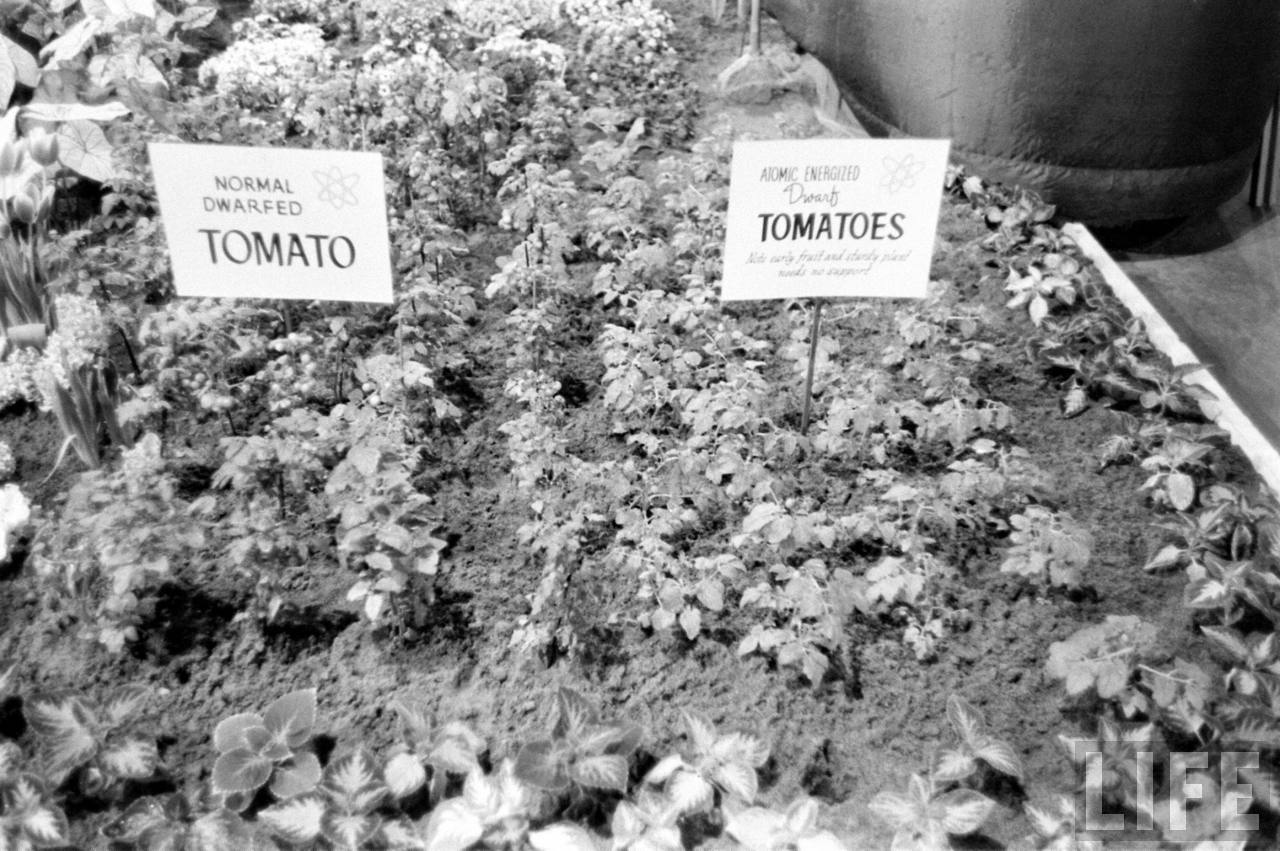

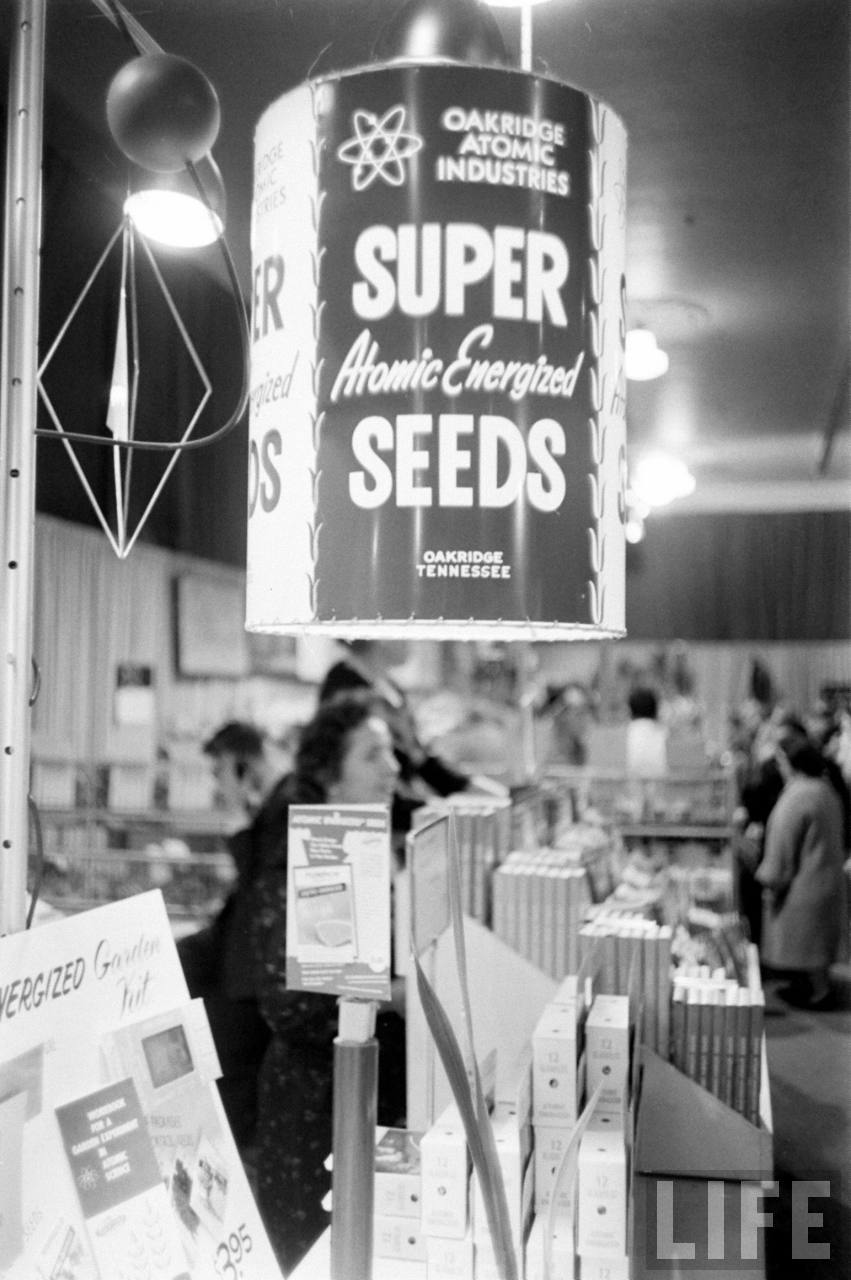

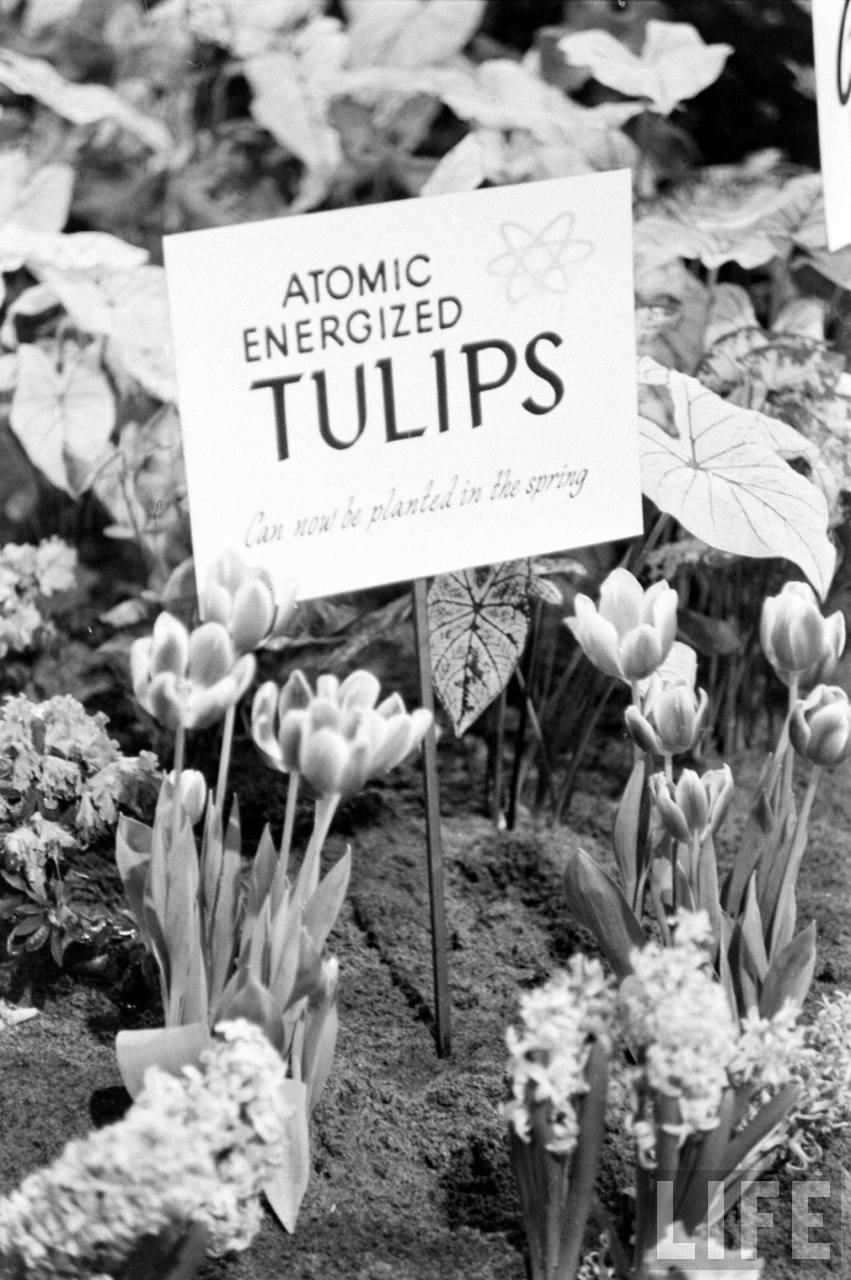

While doing my weekly dig through the LIFE archives, when I came across these eye-opening photographs of an “Atomic Garden Exhibit”, photographed by Frank Scherschel in 1961, and opened a whole new can of worms for myself. The exhibition appears to be encouraging ordinary citizens and green-fingered housewives to buy irradiated, “atomic-energised” seeds and essentially experiment in the field of radiation-induced mutagenesis in their very own backyards.

I had to know more.

Atomic gardening was a post-war fad that was part of the ‘Atoms For Peace’ program, which attempted to find more ‘peaceful’ uses for atomic energy. It pretty much involved exposing plants to radiation, to generate mutations that were bigger, more colorful, resistant to disease and cold weather.

They thought it would end famines and prevent wars, and experiments were initially only conducted in national laboratories in the US, Europe and some Soviet countries. Gamma gardens were set up in controlled grounds, which arranged plants in a circular pattern with a retractable radiation source in the middle. The plants nearest the centre usually died, the ones further out often featured “tumors and other growth abnormalities”; and then there were “the plants of interest”, possessing strange new mutations.

Documentation of atomic gardening outside the laboratory however, is very hard to come by…

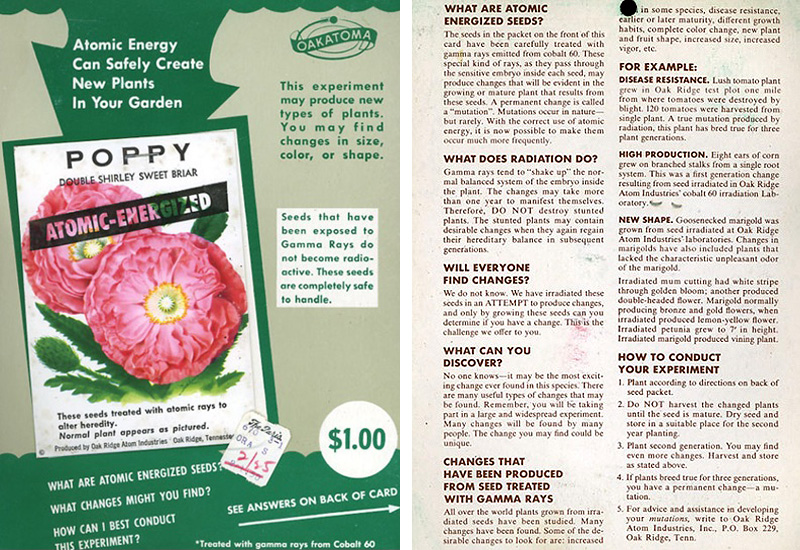

In 1960, a dentist by the name Clarence J. Speas obtained a license for a cobalt-60 source to begin selling atomic products to the public and producing seeds in a backyard cinderblock bunker. He founded Oak Ridge Atom Industries, which you’ll notice in the photographs under the ‘atomic’ plant labels.

(It’s probably no coincidence either that the company bears the same name as Oak Ridge, Tennessee, the very same “top secret atomic city” where 75,000 residents and factory workers had no idea they were processing uranium for the government until the bombs dropped on Hiroshima in 1945).

J. Speas was the marketing pioneer of the citizen ‘atomic gardening fad’ and in fact became the only source for the public to buy irradiated seeds. He marketed the seeds at garden fairs, in magazines, sold them at grocery stores, fundraisers and even encouraged their use in high school science clubs.

But this was all so loosely documented that no one really knows who bought them, how many people experimented with them and more importantly, where these forgotten atomic backyards may be. Nor does anyone really know exactly how Mr. Speas irradiated his seeds and what kind of equipment he used back then. The site of backyard bunker in Tennessee no longer exists today, incorporated into a flood plain as part of a river project long ago, and there are no known documents revealing what happened to the source.

The lack of control in the ordinary citizen experimenting with this stuff is slightly alarming.

But of course, finding the offspring of a 1960 atomic-energized tomato in your backyard is not the only way atomic gardening has ultimately broken free from laboratory control and out into the world. Irradiation of seeds and plant germplasm has resulted in creating many of the most widely grown strains of food crops worldwide. Gamma-mutation is in fact quite common in the foods that we eat on a daily basis. Most of the vegetables and even the meat we pick up from the supermarket aisles actually have a long history of irradiation and genetic manipulation that’s just been swept under the carpet.

Irradiation of seed and plant germplasm, first discovered by Lewis Stadler at the University of Missouri in the 1920s, involves “striking plant seeds or germplasm with radiation in the form of X-rays, UV waves, heavy-ion beams, or gamma rays”. (Stadler died of leukemia in 1954). Interestingly, the UN has been an active participant in irradiation through the International Atomic Energy Agency. It’s also commonly used to prevent the sprouting of certain cereals, onions, potatoes and garlic.

A nanotechnology researcher at the University of Tulsa, Oklahoma and expert on garden history, Paige Johnson said in a 2011 interview that “it would be rare for the consumer to know anything about the genetic history of the food we consume, much less if it came out of the mid-century atomic experiments.”

She highlighted examples such as mint oil from the peppermint plant which is found in most chewing gums and toothpastes. Hundreds of thousands of peppermint stems were irradiated at the Brookhaven National Laboratory from about 1955 onwards, to make them less susceptible to a fungal disease that caused stunting and plant death. This disease-resistant cultivar, known as the Todd’s Mitcham’s cultivar, now produces most of the world’s mint oil today, “with an estimated market value of around $930 million USD”. But of course, “the exact nature of the genetic changes that cause it to be wilt-resistant remain unknown”.

Another readily available atomic mutant Paige Johnson mentions is the ‘Rio Star’ grapefruit, “which accounts for 75% of the grapefruit production in Texas … bred solely to produce flesh and juice that is more red in color than previous varieties.”

Are the ills of today’s society a result of mid-century atomic gardening? Due to a staggering lack of information readily available to the public today, sheltered from discussion by copyright claims and intellectual property privacy, we may never know. Maybe there are no lasting effects, but I’d certainly like to have the choice to find out for myself.