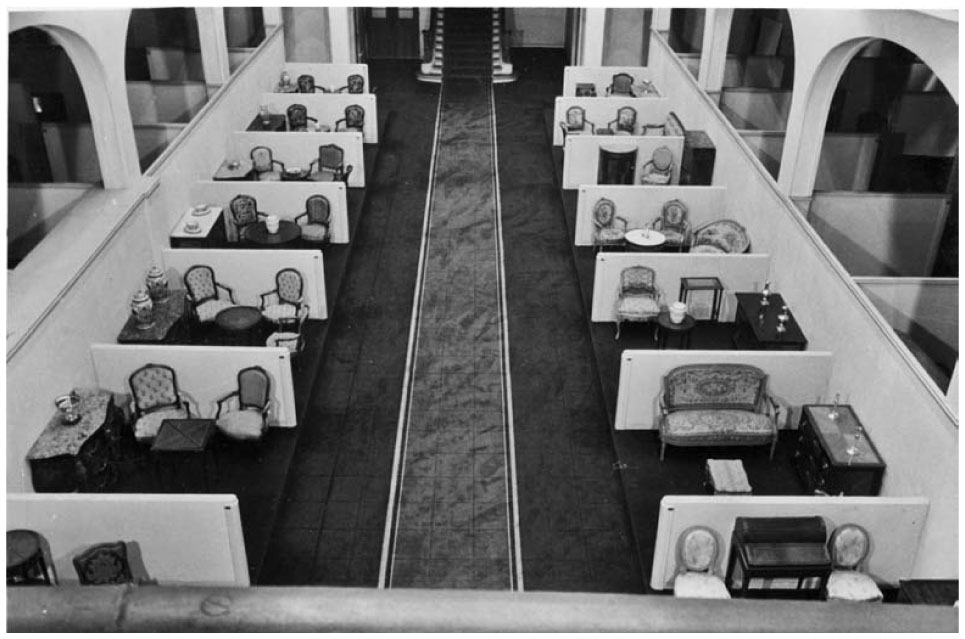

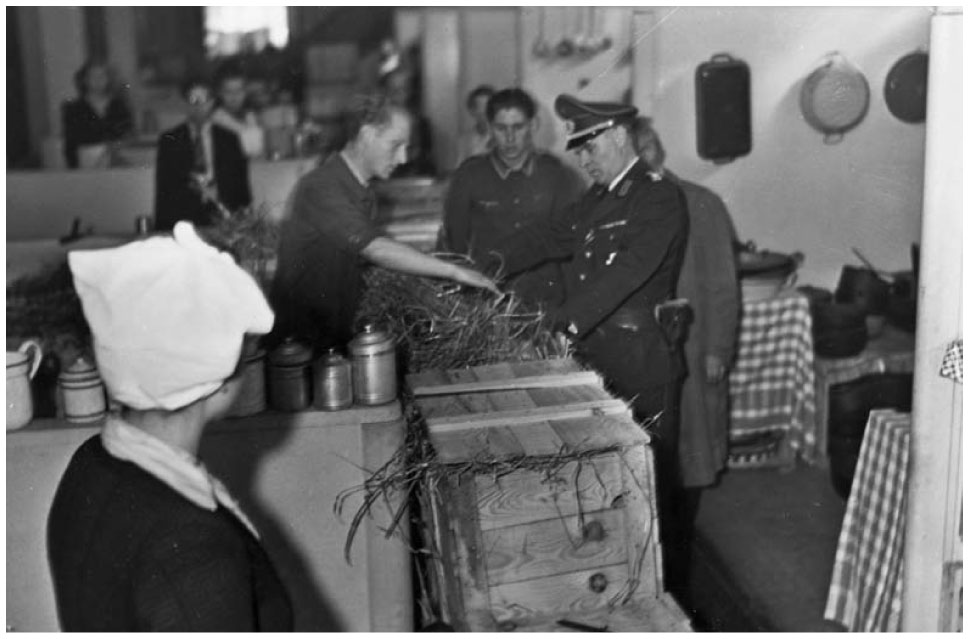

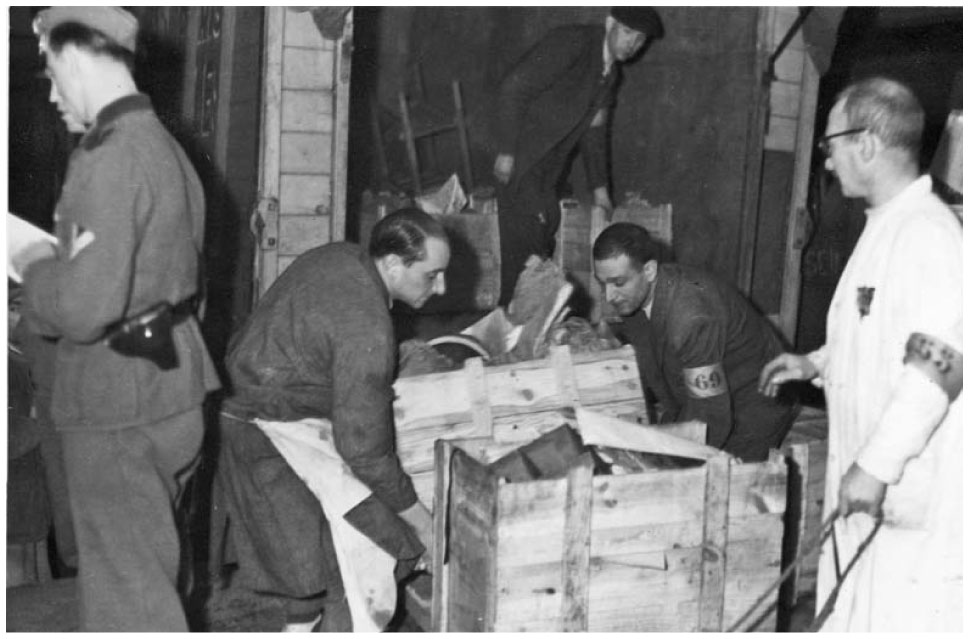

When Paris was liberated from the Nazi occupation in 1944, an album of 85 photographs was found in a shop that had been used by German soldiers assigned to the “Furniture Operation” (Möbel Aktion), the official name for pillaging apartments that had been inhabited by Jews. The snapshots reveal a surreal display of furniture and everyday household goods as if it were an Ikea supermarket, merchandised to catch the shopper’s eye. Except in this case, the “shopper” was the Nazi, the “sales assistants” were Jewish prisoners and the “product” on sale had been looted from their Parisian homes.

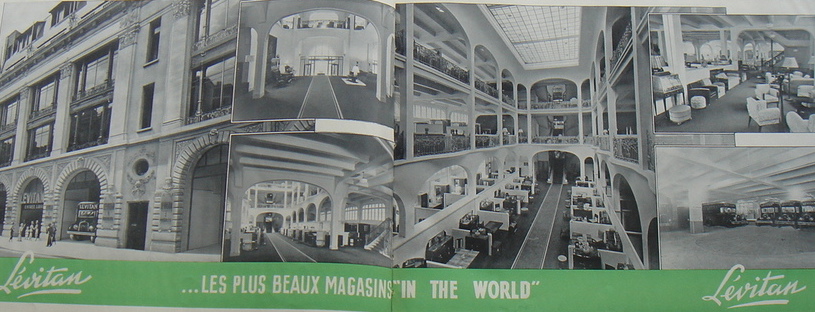

Most of these photographs were taken inside a Parisian department store called Lévitan, opened by a Jewishman called Wolf Levitan in the 1930s to specialise in furniture. Below is brochure shows how the store looked before the Nazis moved in.

Located at 85-87 Rue Faubourg Saint Martin in the 10th arrondissement, the building was confiscated from its former owner, who was forced to hand his entire inventory over to the Germans, even the cash registers. Not only did Lévitan become a place for Nazis officers to browse stolen Jewish household goods to be sent off to Germany, the former furniture store also became one of several Nazi forced labour camps inside occupied Paris, known as the Lévitan camp.

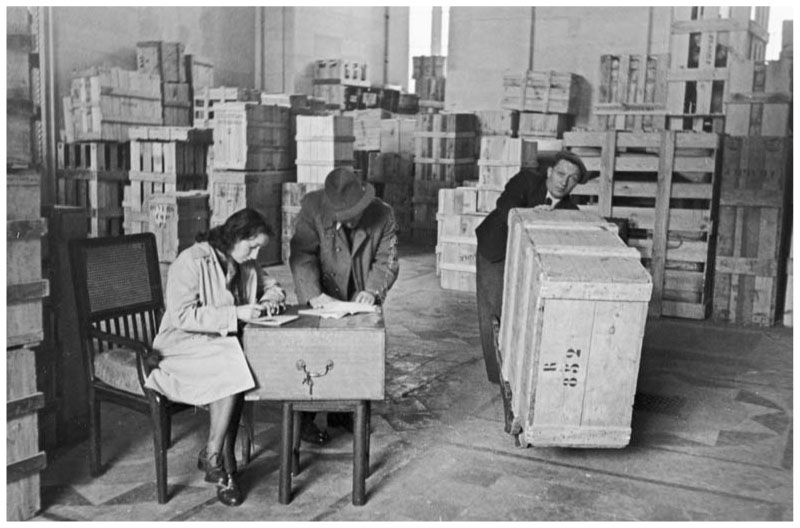

While the first three floors were used for the stock, the fourth was used as a rudimentary dormitory for the 795 Jewish prisoners who were “employed” there between 1940-1944, having been selected from the Drancy internment camp in the northern suburbs (the last stop before being sent to an extermination camp).

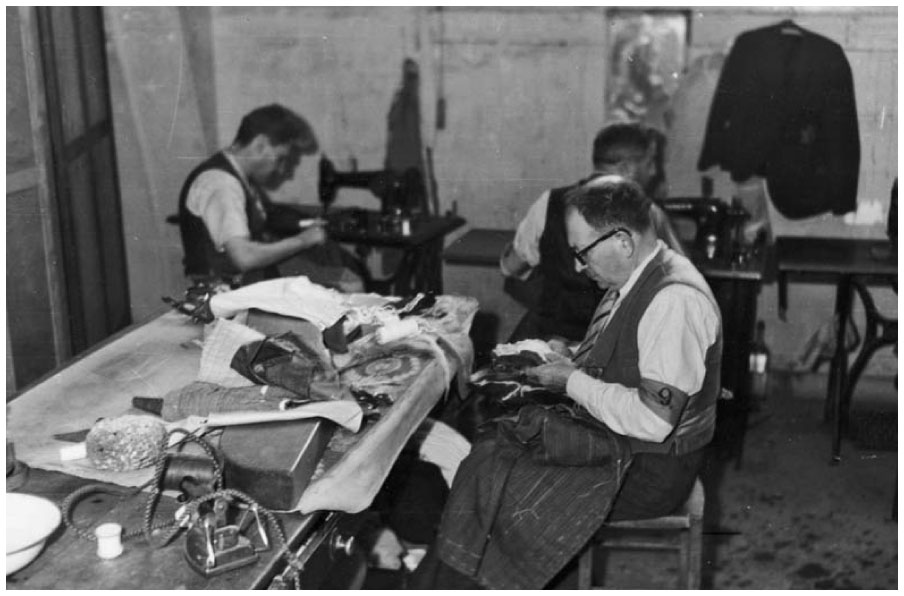

A specialised workforce of mainly female craftsmen, clockmakers seamstresses, potters, restorers and the like, were forced to sort, repair, classify, stack and pack the furniture that had been mercilessly plucked from the homes of their friends, families, neighbours and fellow Parisians, who had already been sent to their deaths.

So much was pillaged from Jewish homes that it wouldn’t have been unlikely that the internees at Lévitan could have come across items from their own home.

They had taken everything, not just the expensive stuff. The displays of the most everyday objects such as kitchen saucepans, household tools, even bedsheets, show it was as much “a process of destruction and anonymization” as it was of greed.

Many Nazi archives and records were destroyed at the end of the war, but not this one. The German soldiers tasked with photographing seized Jewish art and furniture had done such a good job at documenting it all for inventory reasons, it was described as a “taxonomic look at spoils to be restored”, serving like an administrative document, witnessing the pillaging work being carried out. After the war, the discovered album of photographs was brought to Munich by one of the famous ‘Monuments Men’ James R. Rorimer (who inspired Matt Damon’s character in the film) as part of a mission to collect documents and information potentially useful for retracing German-seized artwork in the French capital.

The album is kept in the German Federal Archives in Koblenz, and in a new book by sociologist Sarah Gensburger, all 85 images have been published with fascinating background analysis in Witnessing the Robbing of the Jews. The album also includes some unique photo coverage of the Louvre Museum as a place for the looting, hoarding and theft of the Jews.

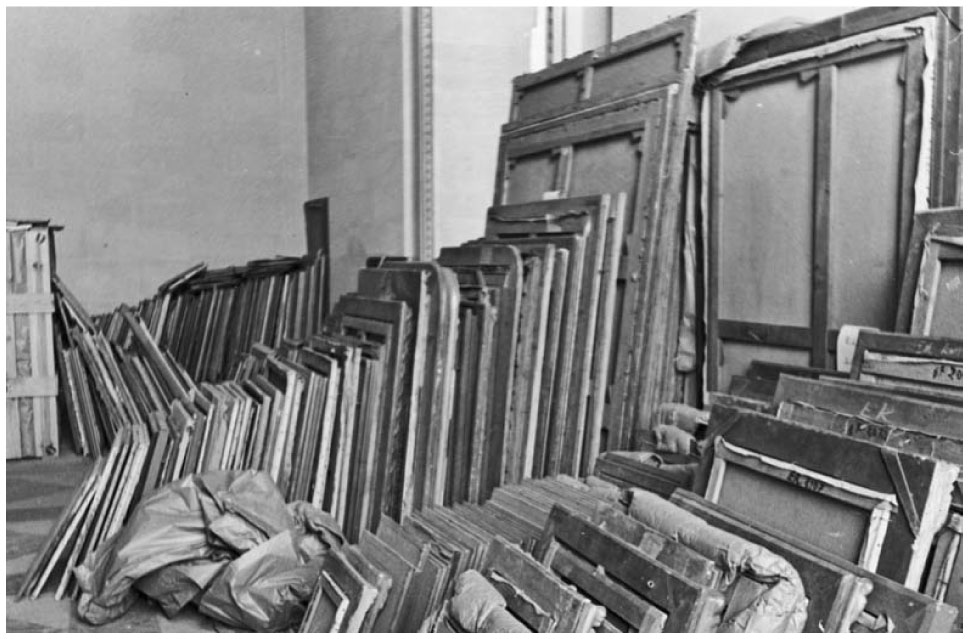

Gensbrger speaks about how one photograph in particular shows how the mission of the Nazi “Furniture Operation” was not so much about making a profit as it was to erase and destroy…

“Approximately seventy paintings are visible in the image, taken in one of the rooms of the Louvre Sequestration area. That only the backsides of the paintings appear in the photograph suggests that as a whole the images were meant as proof of the administrative work accomplished… the photographs were not intended to display the quality of the art. Here the administrative value of the paintings is nothing but the mass they represent, and the quantity of objects reflects … the quantity of individuals concerned by the racial extermination process.”

Of the 795 Jewish prisoners forced to work in the Nazi supermarket of their stolen belonging, 164 were deported to death camps. The former department store on Rue Faubourg Saint Martin is now the seat of an advertising agency. A small plaque on the building’s facade commemorates what happened there.