It has become one with the jungle since the last human inhabitants abandoned its shores in World War II. Ross Island, or as I’ve come to call it, “Jungle Book Island”, was once referred to as the “Paris of the East”, for its opulent architecture and exciting social life amidst the unlikely setting of a tropical island forest. It was the seat of “British Power” in the Andaman Islands, where the colonial government of India chose to set up their remote headquarters in the 1850s. But beneath nature’s impressive takeover of what now looks like a scene from The Jungle Book, there is a much darker story to tell than any children’s tale…

Lead image (c) Stefan Krasowski

(c) IomaDI

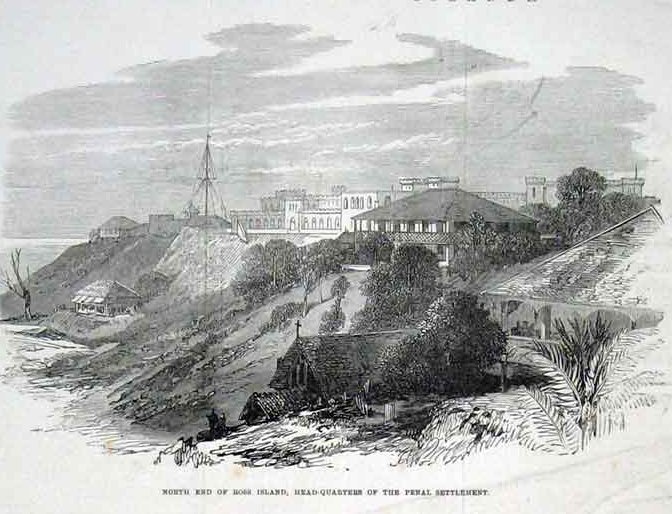

The horrible history of Ross Island begins pretty much as soon as the British set foot on its shores as early as the 1790s. A naval lieutenant in the Bombay Marine, Archibald Blair, found the remoteness of the island an ideal place to establish a penal colony– a.k.a. a colonialist’s gruesome equivalent to Guantanamo Bay. This first attempt to settle the island was thwarted by malaria, but it wouldn’t be long before they would return and take British dominance in India to shameful new heights.

(c) IomaDI

Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857 against the British Raj, Ross Island became a convict settlement for political prisoners, members of the revolution and the Islamic reform movement. It was a “British gulag” no better than Stalin’s forced labor camps or even Hitler’s death camps, where an estimated 15,000 prisoners suffered horrendously under the inhumane treatment and brutalities inflicted by the British authorities, ruled over by a series of merciless Chief Commissioners.

(c) Mark Hollowell

While the penal colony would come to locally adopt the name “Kalapani”, meaning “black water” for the horrific crimes that took place behind prison walls, back in Britain it was being hailed in high society as the “Paris of the East” and a very fortunate post indeed for a British naval officer and his family.

(c) Mark Hollowell

Ross Island had grand ballrooms, lavish manicured gardens, a church, a swimming pool, tennis court, printing press, bazaar, bakery, hospital, all built in colonial style– they had everything a modern settlement could possibly need.

Life on the island was vastly different for prisoners. The first group of 200 prisoners to arrive on Ross Island in 1858 were transported under the control of Dr James Pattison Walker, who wasted no time in putting the convicts to work on the arduous task of clearing the dense forest of the island.

With no basic amenities, they were forced to build the colony from scratch, laying bricks and roads while chained and collared around the neck with identity tags. As more continued to arrive, thousands lived in make-shift tents and huts with leaking roofs. When prisoner numbers rose to 8,000 prisoners, 3,500 died due to sickness.

(c) Mark Hollowell

If being treated like a slave wasn’t awful enough, the prisoners also faced the threat of the indigenous tribes of the Andamans, some of whom were cannibals that tortured and killed them while working in the field during attacks on the colony.

(c) Mark Hollowell

Even when groups of inmates tried to escape from the prison, they were again savagely attacked by the indigenous tribes and forced to turn back to the camp knowing they would be promptly sentenced to death. After one particular failed escape, more than 80 men were hanged in a single day at the command of Dr. James Pattison Walker. Ironically, even after the Andamanese tribes had launched several attacks on the colony, including a significant battle in 1859 that came to be known as the “Battle of Aberdeen” (the first initiative by the local people to seek independence from colonial rule), the British then changed their approach in handling the indigenous people, taking steps to seek peace with them and win them over, even appointing an officer to look after their welfare.

Meanwhile, the inmates of Ross Island, who had been fighting for the very same freedom, continued to be treated as slaves. The barbaric Dr. Walker who put his convicts in iron collars to prevent escape, wasn’t removed from his position until it was reported that he wanted to brand his inmates on their forearms with information of the crime and sentence they had been given.

Sounds like Hitler’s kind of hero.

(c) Ivor Tiller

Even after Walker’s replacements made efforts to “improve” conditions at the prison camp, inmates still chose suicide over life on Ross Island. When an honorable officer of the Indian Army, Sir Robert Napier came to investigate the conditions, he found them “beyond comprehension” as there was no food, clothing and shelter provided to the convicts. When the inmate population swelled to 10,000, doctors reported that only 45 prisoners could be considered medically fit. The camp had a death rate of 700 per year.

(c) David Dorren

At this time, the British authorities had also embarked on testing of pharmaceutical drugs by forcibly feeding them to their 10,000 prisoners. Side effects of the untested drugs included severe nausea, dysentery and depression. Prisoners began injuring fellow inmates with the intent of being caught by authorities, just so they could end their own suffering by hanging. Authorities responded with flogging, reducing food rations and even reportedly making them sleep in cages.

A renowned poet, intellectual and mentor of a British major-general, who had been accused of inflaming the Muslims of Delhi to wage “jihad” against the British Raj, died at the colony in 1861. One political prisoner spent 47 years incarcerated on Ross Island. He was released in 1907 for good behaviour.

(c) David Dorren

Today, there are only remnants of the past; buildings strangled by branches, a church tower sprouting a tree, a bakery missing its roof, the pool house growing roots. In 1941, an earthquake shook the small island of one square mile, damaging much of the infrastructure and causing most inhabitants to leave the island, shifting the headquarters to the nearby Port Blair. A year later, in the midst of World War II, the vulnerable island was invaded by the Japanese, forcing the remaining British to evacuate entirely. When the Japanese occupation of the island ended in 1945 at the end of the war, Ross Island was never re-inhabited and nature’s take-over began.

(c) IomaDI

Despite being uninhabited, the “jungle-clad Lost City” has since become somewhat of a tourist attraction, reachable by a short boat ride from a water sports complex in Port Blair. A small museum and cemetery are managed by the Indian Navy, which controls the island and requires every visitor sign on upon entering. The museum has a small collection of old records, but until I reach the tropical shores of Ross Island myself, I’ll have to get back to you on just how much has been left off the information plaques. I have a feeling nature might not be the only one trying to bury the true horrors of “Jungle Book island”.