It’s almost easy today, a century later, to laugh about the questionable medical inventions of yesteryear. But another hundred years from now, will people be laughing at the harmful products you and I use today?

Here on MessyNessyChic, we’ve become quite familiar with the generation that brushed its teeth with radioactive toothpaste and that fell for the radioactive quackery of the past, but if you have some catching up to do, I suggest you do that first before reading on.

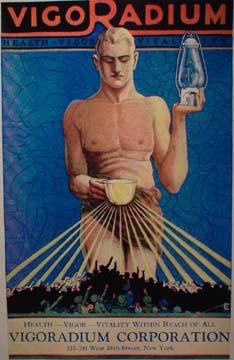

It’s a subject that seems to endlessly shock me with its array of lethal inventions that were available during the height of the fad in the early 20th century. Most recently, I learned about the inventions which tied in radioactivity with sexuality.

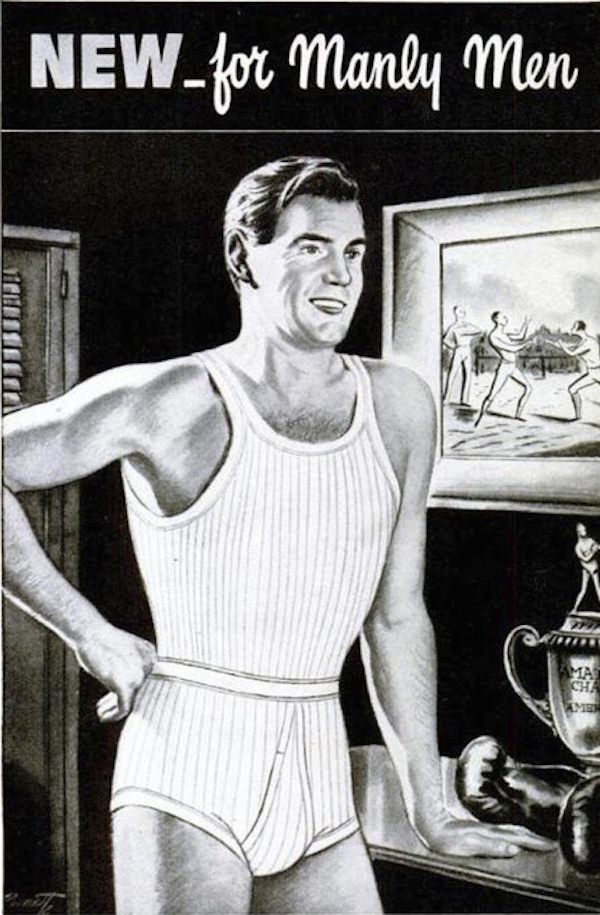

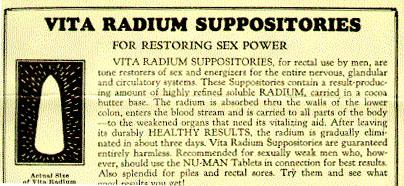

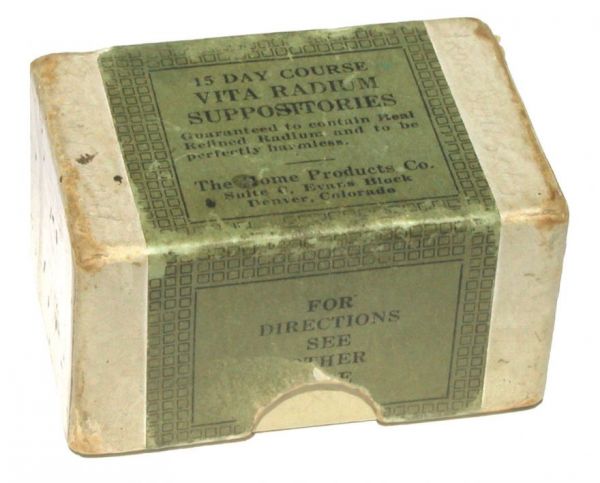

They were making radioactive athletic supporters for weak sagging men, drying out boar’s testicles and making them radioactive to improve your romantic talent. There were even radium suppositories for men and women, promising to deliver a sense of vitality and energy.

Here’s an extract from a Vita Radium Suppository ad:

Now Bubble Over with Joyous Vitality Through the Use of Glands and Radium

“Properly functioning glands make themselves known in a quick, brisk step, mental alertness and the ability to live and love in the fullest sense of the word . . . A man must be in a bad way indeed to sit back and be satisfied without the pleasures that are his birthright! . . . Try them and see what good results you get!” (Vita Radium Suppositories are shipped in a plain wrapper for confidentiality.)

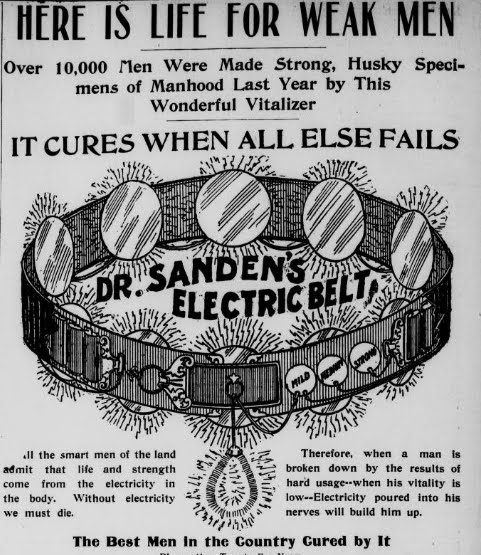

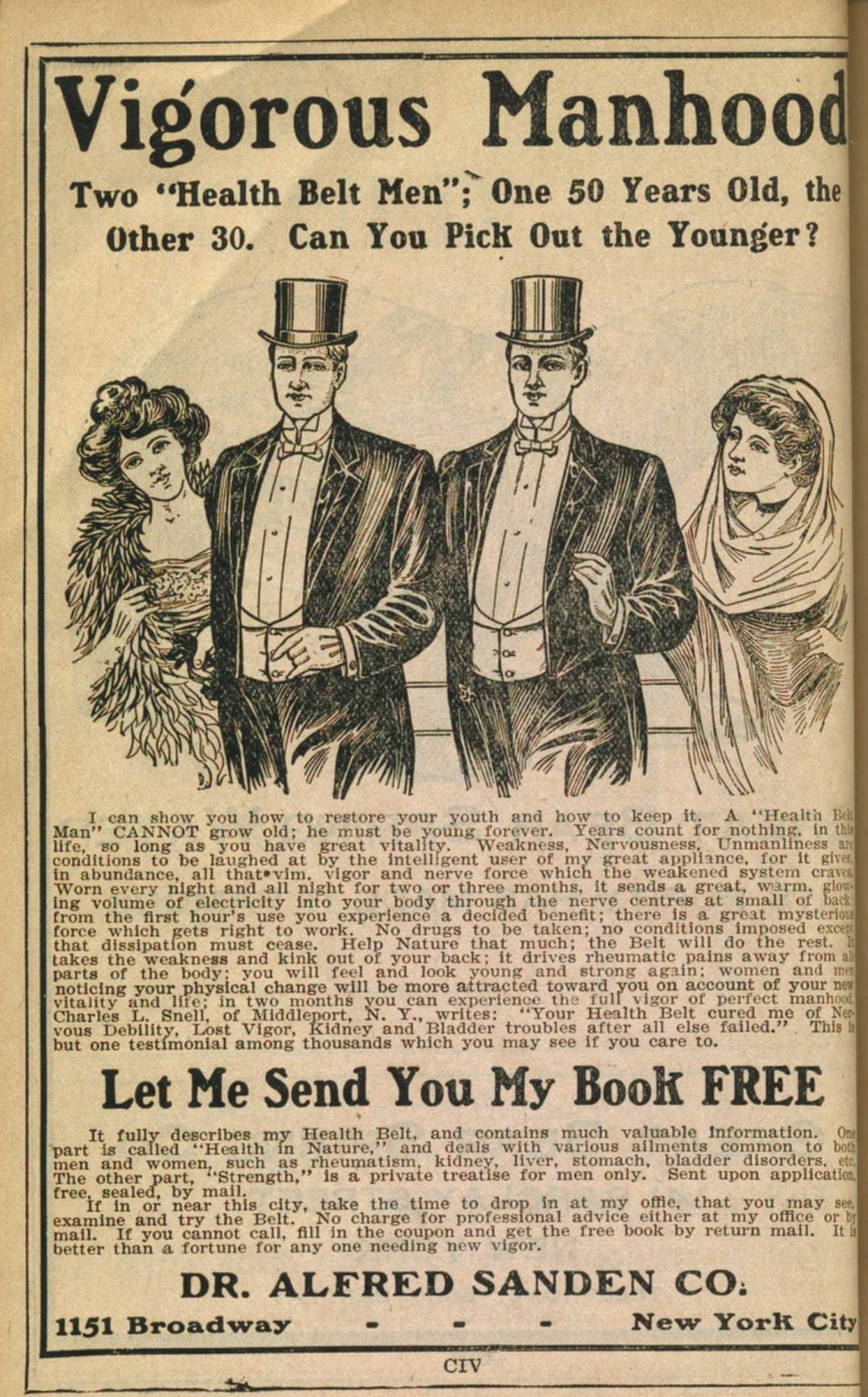

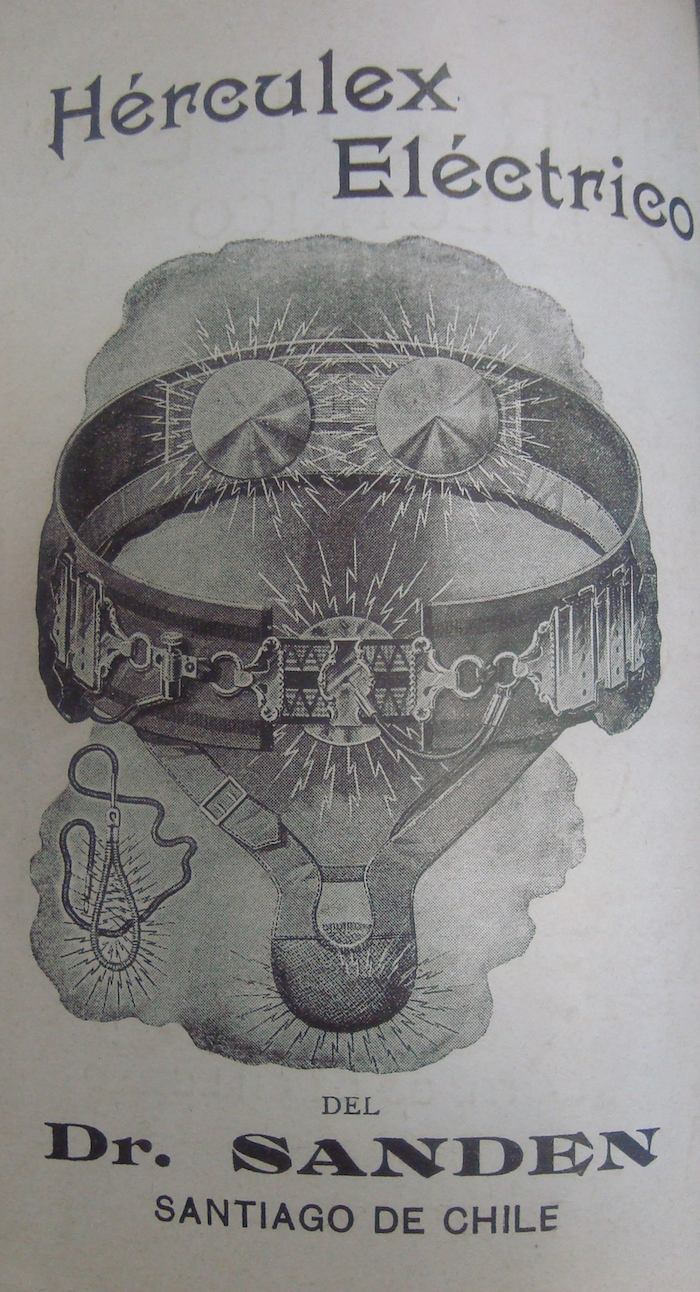

Just as America’s favourite new miracle ingredient at the dawn of the 20th century was radium, a few decades earlier it had been electricity that was all the rage. Potentially lethal radioactive products promising to cure impotency were really the progenitors of earlier quack inventions such as the infamous Dr. Sanden’s Electric belt.

The late 19th century product claimed to transform a weak man’s vigor and boasted to have made thousands men into strong, husky specimens of manhood.

The belts produced an electric current when the built-in plates were moistened, which would supposedly charge a “reduced nervous force and revitalise bodies”.

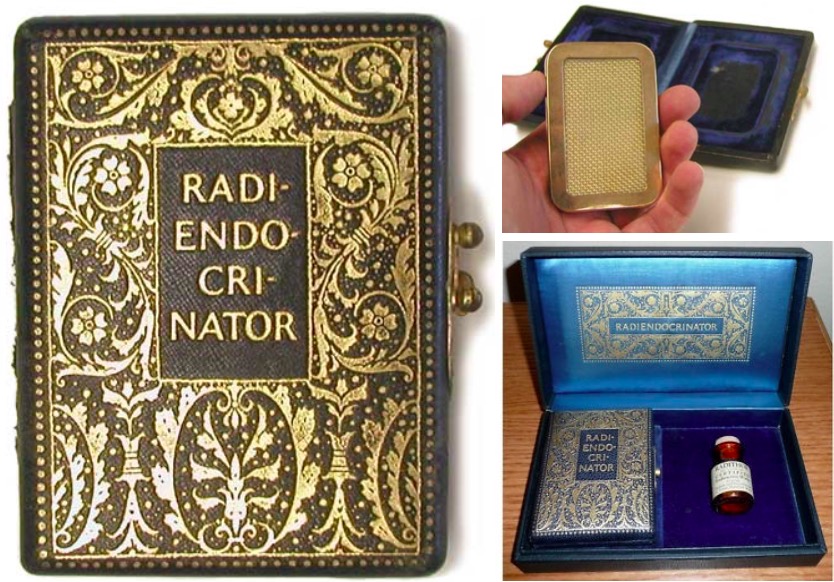

In the early 1920s, a Harvard dropout calling himself “Dr” Bailey, who had already served time in jail for advertising fraud while selling radioactive flu medicine, began marketing the Radioendoctrinator, a gold-plated radium-containting belt. He argued that it could rejuvenate various parts of the body depending on where it was worn. For “weak or sagging men” for example, it could be worn with an included suspensory attachment under the scrotum.

For those desperate to cure impotence, wearers were instructed to position the radium “under the scrotum as it should be. Wear at night. Radiate as directed…”

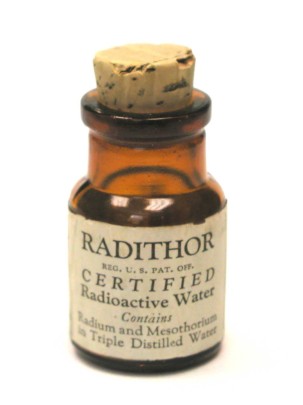

The $150 contraption was also sold with Radiothor, which were little bottles of radioactive water advertised as “a Cure for the Living Dead”, also made by Bailey’s radium laboratories in New Jersey between 1918 and 1928. Alongside the Radioendoctrinator, Bailey began marketing the bottles at $1.25 to “improve your romantic talent”.

One of “Dr” Bailey’s customers was a wealthy young Yale alumni by the name of Eben Byers who had injured his arm, which he found interfered with both his love life and his golf game. He drank 1,400 bottles of the stuff and everything was going fine until his jaw fell off.

That’s when the public started to realise the dangers of radium. Three months after he was buried in a lead-lined coffin to prevent radiation leakage. Radiathor was pulled from the market. His death led to a heightened awareness of the dangers of ingesting radioactive materials, and to the adoption of laws that increased the powers of the FDA.

“Dr” William Bailey who is estimated to have sold more than 400,000 bottles of Radithor over the years and claimed to have drunk more radioactive water than any living man, died of bladder cancer in 1949.

For the first half of the twentieth century, radium had been big business and companies came up with the cure for practically anything that ailed you. But unfortunately, no one had a cure for the cure.