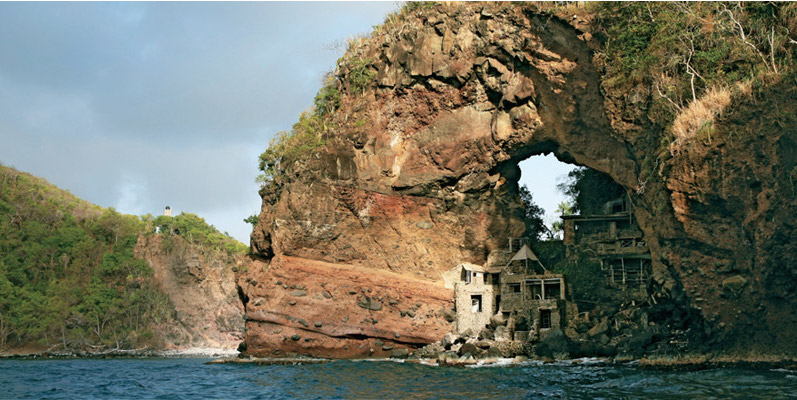

At night, the rising moon peers through the natural volcanic arch, revealing the silhouettes of windows and doorways alluding to a crumbling fortress, guarding a paradise lost. It shares its walls with the rocks, built haphazardly into the Caribbean cliff on the western tail of the island of Bequia, but the rooms are empty, the whole structure eerily lifeless. Like the centrepiece of a mystery movie’s opening scene, the magic of Moonhole is as much a sight to be seen as it is a story to be told…

(c) Douglas Friedman/ DuJour

In the late 1950s, a young-at-heart American couple, Tom and Gladdie Johnston, had retired from the advertising business and decided to chuck it all and move to Bequia, a quiet sandy paradise void of chain hotels, overshadowed by its southern neighbour, Mustique, the preferred island getaway of royalty and rockstars.

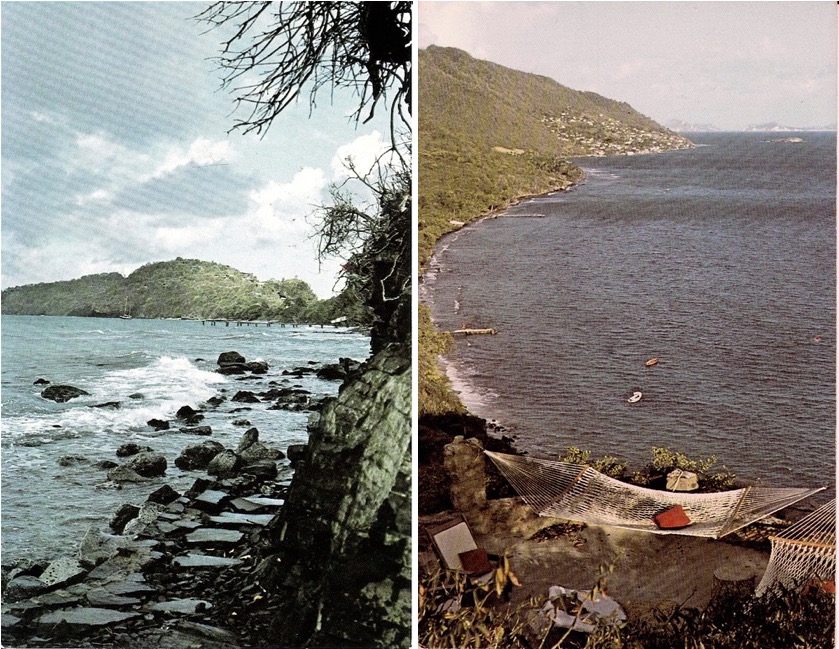

They took over a small 9-room inn called the Sunny Caribbee Hotel and became friendly with a local island family who owned the uninhabited western end of Bequia (pronounced “Beck-way”). Eager to discover more of their new island home, they took up the family’s invitation to visit a strange geological arch formation known as the Moonhole. At the time, that end of the island was accessible only by a watery trek along the bottom of the cliffs.

They began to picnic and camp there, and it quickly became the couple’s favourite spot on the island. In the 1960s, they ended up buying the entire 30-acre tract on a whim and started building a house beneath the natural arch of volcanic rock, working with local masons from a nearby village who walked in daily to bring food and supplies.

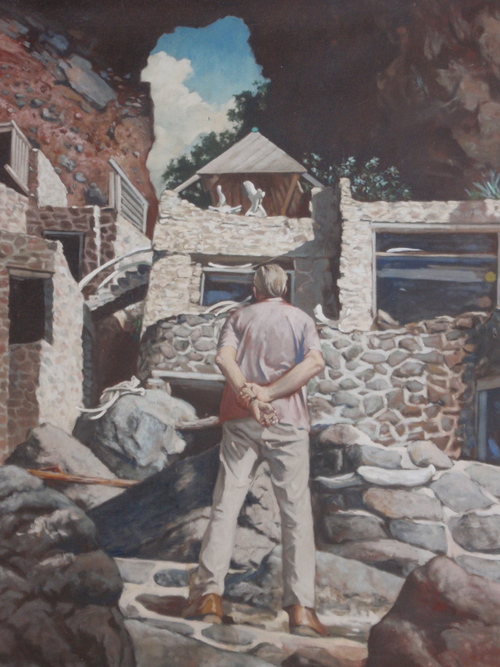

In the early stages, the Johnstons lived amongst the Moonhole’s rocks in a Swiss Family Robinson daze. There were just boards across rocks under the natural volcanic roof, the end of their bed loomed frighteningly close to the drop down to the water’s edge and “there was nothing to keep you from falling out of the kitchen”, remembered Gladdie Johnston in an early interview.

The fact that Tom had zero formal training as an architect didn’t stop him as he gradually moulded his mini island citadel of rooms open to the elements, connected by twisting staircases on several levels winding up from the sea. It was all built on his philosophy that “a house should not be built to be looked upon, but designed so its occupants can look outward and live outwardly, enjoying the world”. One of largest guest rooms of the house was named the Whale Room, because when you woke up in the morning, “without lifting your head from the pillow, you could see whales spouting in the distant sea”.

More of a hamlet than a house, Moonhole was almost entirely decorated with castaway material; shipwrecked or native wood were used as beams and flooring, anchor chains as railings, whalebones recovered from the sea as bannisters and chairs and fishnet floats as table bases. It became a common saying on Bequia, “Don’t throw anything away. Sell it to Tom Johnston.”

Without wells or electricity, they collected rainwater from the so-called roofs and stored it in cisterns for bathing and washing. The floors were not level, the giant windows were glassless and most rooms didn’t have enough walls to be considered a real room, assembled around a tree or nooks in the island rock. When the secretary of the local government came to the Johnston home to measure their new home for tax purposes, “he couldn’t tell exactly where the tax-free outdoors ended and the taxable indoors began”.

But one thing was for sure, the Johnstons had found paradise.

Found on the Getty Image archives

When they began inviting friends and relatives to their new home, entertaining them at the bar fashioned from the recovered jaw bone of a humpback whale, visitors were instantly enamoured with the Crusoe lifestyle the couple had created for themselves– and they wanted it too. But this is where the Johnston’s paradise found, perhaps began to lose its way.

The Moonhole house had attracted the attention of the outside world, with publications in The New York Times and National Geographic. Persistent paradise-seekers urged Tom to build houses for them, and very quickly, the former ad man who had “never put together anything more substantial than a sandwich” was now an in demand architect on the island of Bequia. He agreed to build their houses and in 1964, Tom and Gladdie founded the Moonhole Company Limited, aimed at developing the Moonhole property as what he called a “people preserve” for writers, artists, friends and people to get away from it all. Over thirty years, he built sixteen more houses, a commissary, office, living quarters for Moonhole staff and a gallery where the community could congregate every Sunday. But expanding didn’t mean getting rid of his strict eco-friendly values…

The Moonhole house had attracted the attention of the outside world, with publications in The New York Times and National Geographic. Persistent paradise-seekers urged Tom to build houses for them, and very quickly, the former ad man who had “never put together anything more substantial than a sandwich” was now an in demand architect on the island of Bequia. He agreed to build their houses and in 1964, Tom and Gladdie founded the Moonhole Company Limited, aimed at developing the Moonhole property as what he called a “people preserve” for writers, artists, friends and people to get away from it all. Over thirty years, he built sixteen more houses, a commissary, office, living quarters for Moonhole staff and a gallery where the community could congregate every Sunday. But expanding didn’t mean getting rid of his strict eco-friendly values…

Still intimately connected with nature, the houses were built with the same local stone and Tom still constructed his rooms and stairways around trees rather than cutting them down; the lines ever blurred between indoors and out. Nor did he budge on building a road into the properties and they relied on solar electricity. Often referred to as the charismatic self-appointed rajah of Moonhole, Tom personally vetted each new homeowner.

They had to trust his style, be compatible with him and accepting of his rules and decisions without question. But they were rarely disappointed with the finished result of the cave-like dwellings he built for them within his tropical colony.

The Johnstons also remained devoted to the local people who staffed and built Moonhole over the years, providing them with jobs and covering medical and educational expenses. They also set up a local charity which continues to help those in need on the island today.

Tom Johnston died in 2001, and in his will, he left his controlling interest in Moonhole Company Limited, a trust that would be dedicated to preserving the “unique architecture, lifestyle, and vision of the Johnstons” and to protecting the wildlife and marine life.

But things went south pretty quickly.

The community spirit faded in Tom’s absence, original homeowners passed away or became too elderly to visit and the next generation fought for control, lawsuits were filed, even Johnston’s own son tried to contest his father’s will. Contributions to the cost of upkeep dwindled, while some properties were altered in ways that totally contrasted the Johnstons’ vision of a simplistic eco-paradise to blend in with the natural landscape. As Moonhole began to lose its once devoted but now-disillusioned staff, many of the houses became seriously neglected.

The original Moonhole villa itself under the soaring natural arch became so unsafe from neglect, that it’s now been completely abandoned and is strictly condemned to trespassers since rocks began falling from the archway, crashing onto the roof.

A quick Google of “moonhole villa for sale” and you’ll find several property listings for the villas, with asking prices ranging from $325,000 to $2 million, including this one at a “reduced price!”, accompanied by photos of one of Johnston’s homes in shambles, with his once admired whalebone sculptures strewn around the forgotten living rooms and terraces.

A quick Google of “moonhole villa for sale” and you’ll find several property listings for the villas, with asking prices ranging from $325,000 to $2 million, including this one at a “reduced price!”, accompanied by photos of one of Johnston’s homes in shambles, with his once admired whalebone sculptures strewn around the forgotten living rooms and terraces.

While the Moonhole of today may be run by a company of trustees rather than a single charismatic and slightly mad self-made architect with a utopian vision, there is still undoubtedly a piece of paradise to be found within this secret caribbean colony of Robinson Crusoe dreamers.

The lawsuits are now finally over after the court’s ruling in favor of the trust, which is seeing some of Moonhole’s most faithful residents returning to ensure it rises again.

The staff are coming back, the remaining homes still owned by the trust are being renovated and made available to rent, which prevents them from falling into disrepair and pays for the upkeep of the community as well as the continued protection of the local marine and wild life. If you’re interested in reliving the real-life story of the “Swiss Family Johnston”, the 2-3 bedroom villas will set you back $1,500 a week. The Moonhole Company stresses however that this part of Bequia is a private nature preserve, not a tourist destination.

The rent includes the services of a talented cook and friendly housekeeper, members of the Moonhole family for 20 years. And while you’re there, should you bring a copy of Moonhole: The Rise and Fall of an Island Utopia, written by Charles Brewer, one of the homeowners originally chosen by Tom Johnston himself to tell the story of his crazy Crusoe dream, don’t go waving it around the beach as the Moonhole trustees maintain that Tom would not have approved the “many falsehoods published in this disappointing book” after his death.

Perhaps only the few who can get close enough to paradise on Earth will truly understand what Proust meant when he said, “The true paradises are the paradises that we have lost.”