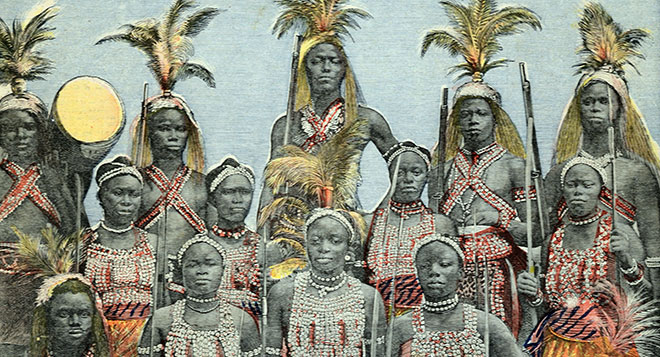

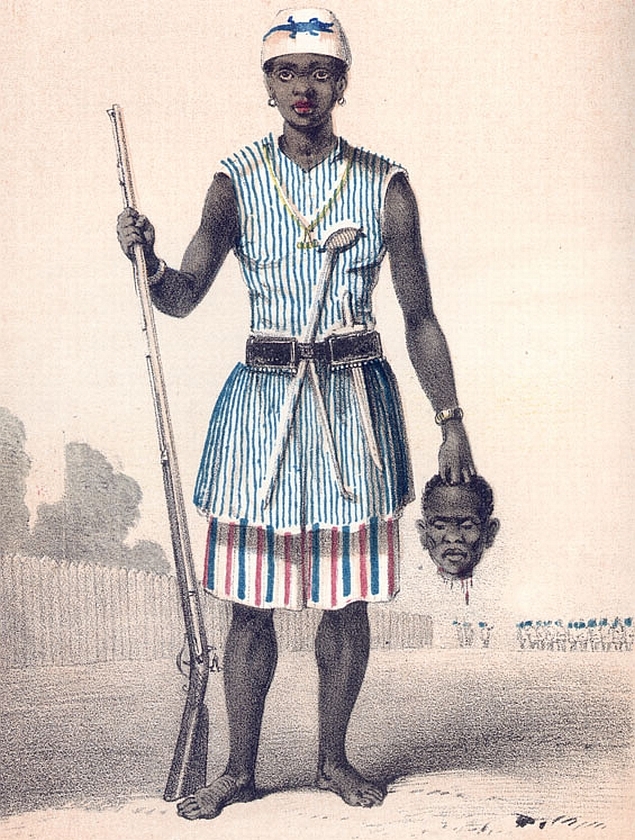

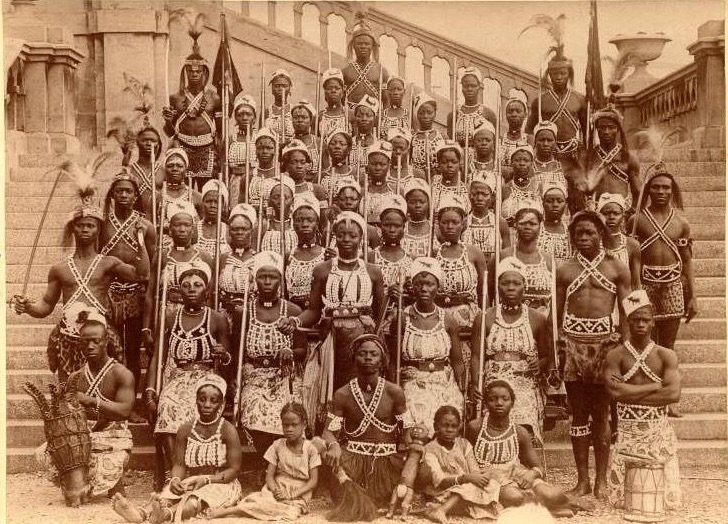

From daughters to soldiers, from wives to weaponized, they remain the only documented frontline female troops in modern warfare history. A sub-saharan band of female terminators who left their European colonisers shaking in their boots, foreign observers named them the Dahomey Amazons while they called themselves N’Nonmiton, which means “our mothers”. Protecting their king on the bloodiest of battlefields, they emerged as an elite fighting force in the Kingdom of Dahomey in, the present-day Republic of Benin. Described as untouchable, sworn in as virgins, swift decapitation was their trademark.

These are not mythical characters. The last surviving Amazon of Dahomey died at the age of 100 in 1979, a woman named Nawi who was discovered living in a remote village. At their height, they made up around a third of the entire Dahomey army; 6,000 strong, but according to European records, they were consistently judged to be superior to the male soldiers in effectiveness and bravery.

Their history traces as far back as the 17th century, and theories suggest they started as a corps of elephant hunters who impressed the Dahomey King with their skills while their husbands were away fighting other tribes. A different theory suggests that because women were the only people permitted in the King’s palace with him after dark, they naturally became his bodyguards. Whichever is true, only the strongest, healthiest and most courageous women were recruited for the meticulous training that would turn them into battle-hungry killing machines, feared throughout African for more than two centuries.

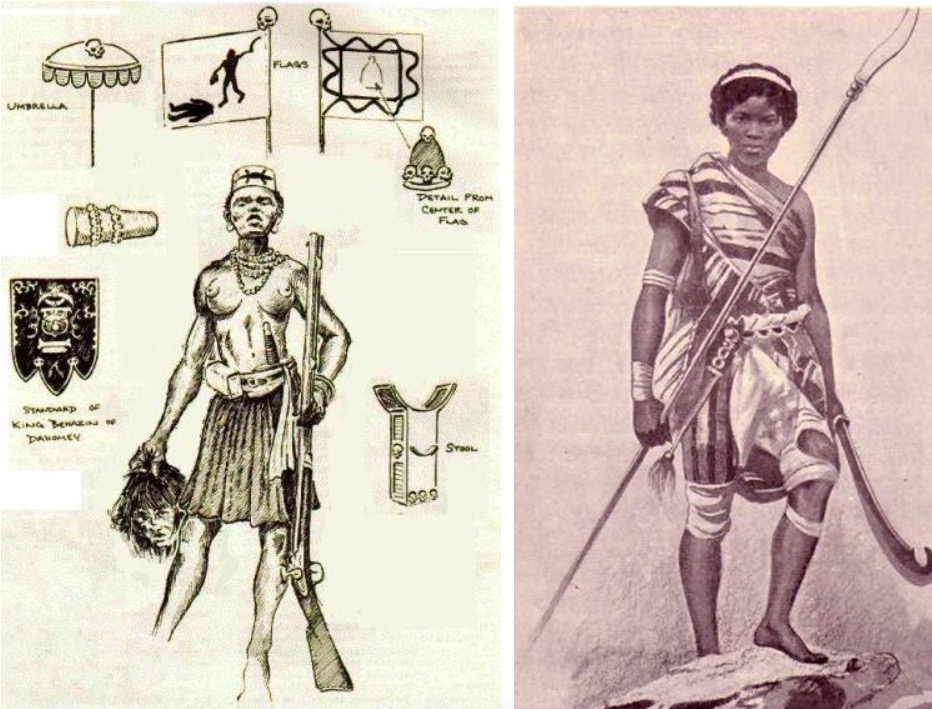

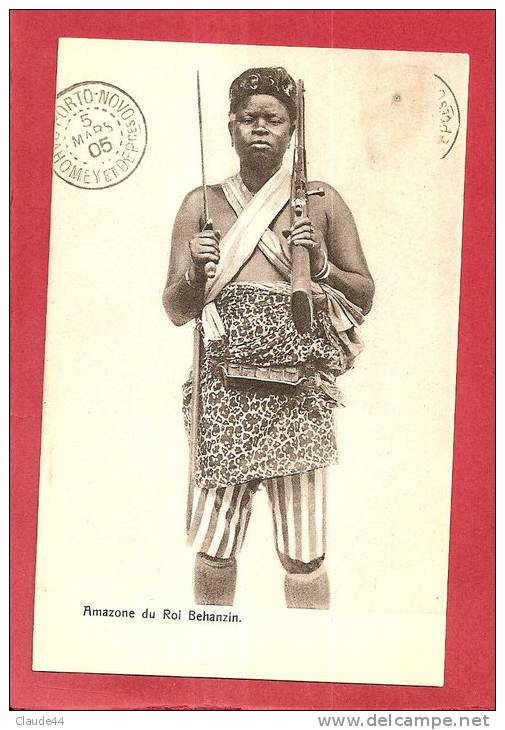

They were armed with Dutch muskets and machetes and by the early 19th century, they had become increasingly militaristic and fiercely devoted to their King. Girls were recruited and given weapons as young as eight years-old, and while some women in society became soldiers voluntarily, others were also enrolled by husbands who complained of unruly wives they couldn’t control.

From the start, they were trained to be strong, fast, ruthless and able to withstand great pain. Exercises that resembled a form of gymnastics included jumping over walls covered with thorny acacia branches. Sent on long 10-day “Hunger Games” style expeditions in the jungle without supplies, only their machete, they became fanatical about battle. To prove themselves, they had to be twice as tough as the men. Often seen as the last (wo)men standing in battle, unless expressly ordered to retreat by their King, the Dahomey women fought to the death– defeat was never an option.

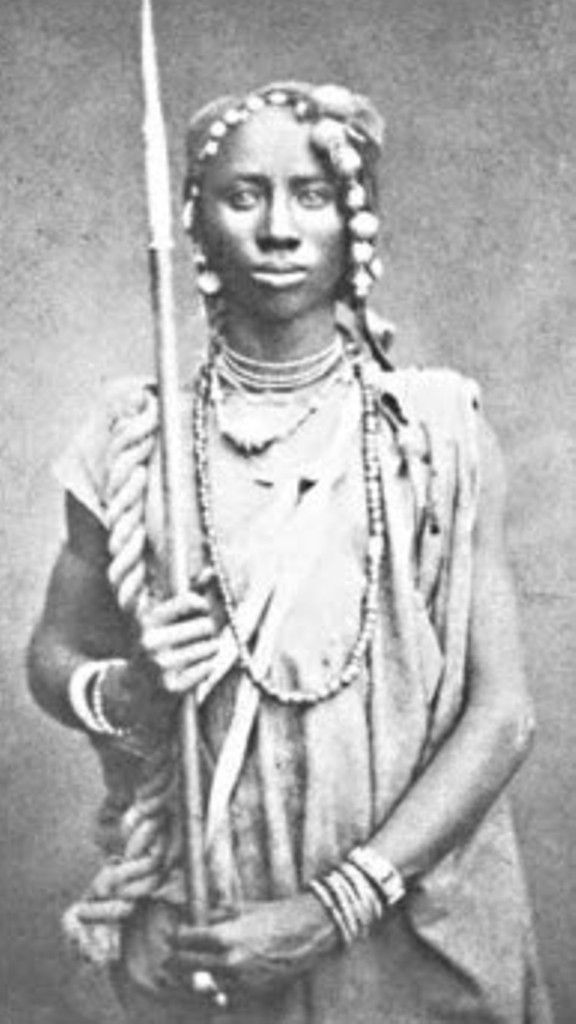

The N’Nonmiton women were not allowed to marry or have children while serving as soldiers and were considered married to the King in a vow of chastity, focused solely on their semi-sacred status as elite warriors. Not even the King dared to break with their celibacy vows, and if you were not the King, to even touch these women meant certain death.

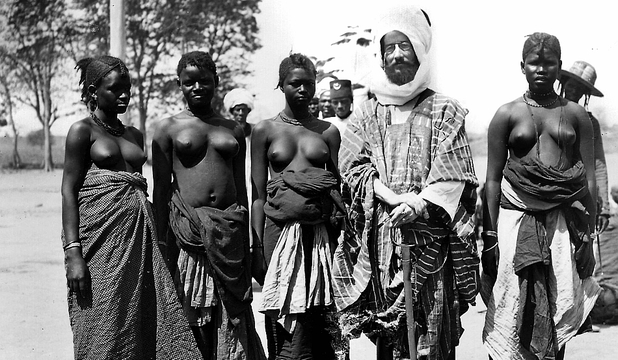

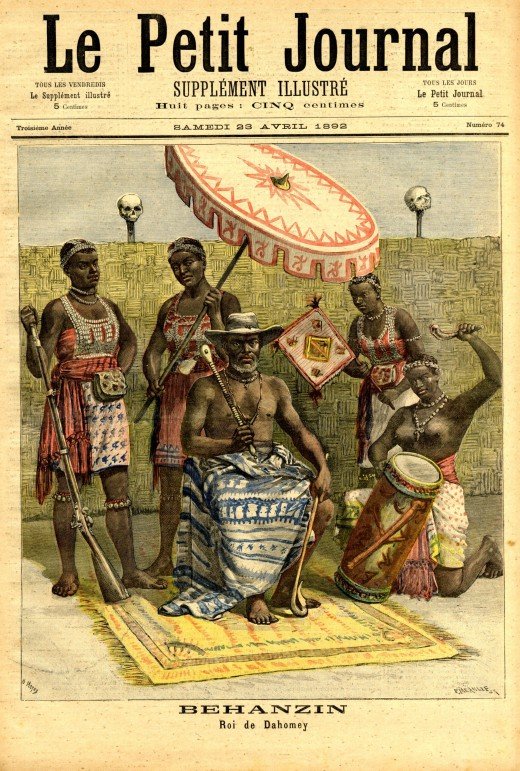

In the Spring of 1863, the British explorer Richard Burton arrived in the West African coastal nation of Dahomey on a mission for the British government, trying to make peace with the Dahomey people. The Dahomey were a warring nation who actively participated in the slave trade, turning it to their advantage as they captured and sold their enemies. But it was the elite ranks of Dahomey female warriors that amazed Burton.

“Such was the size of the female skeleton and the muscular development of the frame that in many cases, femininity could be detected only by the bosom.”

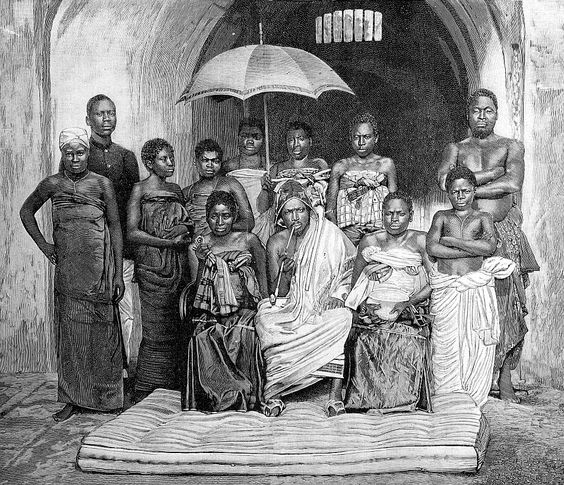

The female soldiers were said to be structured in parallel with the army as a whole, with a central elite wing acting as the king’s bodyguards, flanked on both sides, each under separate female commanders. Some accounts even say that each male soldier in the army had a N’Nonmiton counterpart. Burton gave the army the nickname of “Black Sparta”.

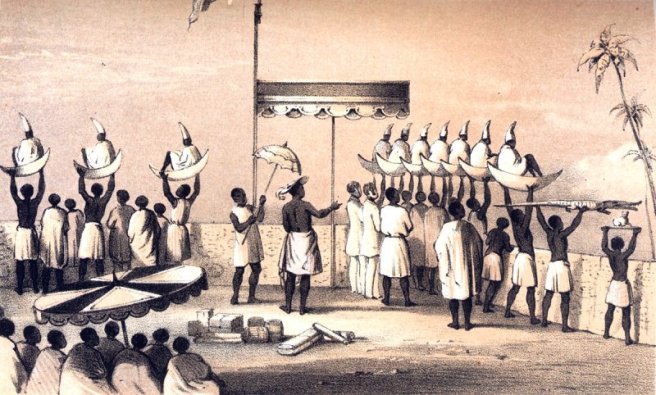

The women learned survival skills, discipline and mercilessness. Insensitivity training was a key part of becoming a soldier for the King. As illustrated above, one recruitment ceremony involved testing if potential soldiers were ruthless enough to throw bound human prisoners of war to their deaths from a fatal height.

A French delegation visiting Dahomey in 1880s reported witnessing an Amazon girl of about sixteen during training. The records note that she took three swings of the machete before completely removing the head of a prisoner. She wiped the blood from her sword and swallowed it. Her fellow Amazons screamed in frenzied approval. It was customary in the region as warriors of the time to return home with their heads and genitals of opponents.

Despite the brutal training they were to endure as the King’s soldiers, for many women, it was a chance to escape lives of forced domestic drudgery. Serving in the N’Nonmiton offered women the opportunity to “rise to positions of command and influence”, taking prominent roles in the Grand Council, debating the policy of the kingdom. They could even become wealthy as single independent women, living in the King’s compound of course but surrounded with supplies, tobacco and alcohol at their disposal. They all had slaves too. Stanley Alpern, author of the only full-length English-language study of them, wrote “when Amazons walked out of the palace, they were preceded by a slave girl carrying a bell. The sound told every male to get out of their path, retire a certain distance, and look the other way.”

Even after French expansion in African in 1890s subdued the Dahomey people, their reign of fear continued. Uniformed French soldiers who took Dahomey women to bed were often found dead in the morning, their throats slit open. During the Franco-Dahomean Wars, many of the French soldiers fighting in Dahomey had hesitated before shooting or bayoneting the N’Nonmiton. Underestimating their female opponents led to many of the French casualties as special units of the female Amazons were assigned specifically to target French officers.

By the end of the Second Franco-Dahomean War, the French prevailed, but only after bringing in the Foreign Legion, armed with machine guns. The last of the King’s force to surrender, most of the Amazons died in the 23 battles fought during the second war. The legionnaires later wrote about the “incredible courage and audacity” of the Amazons.

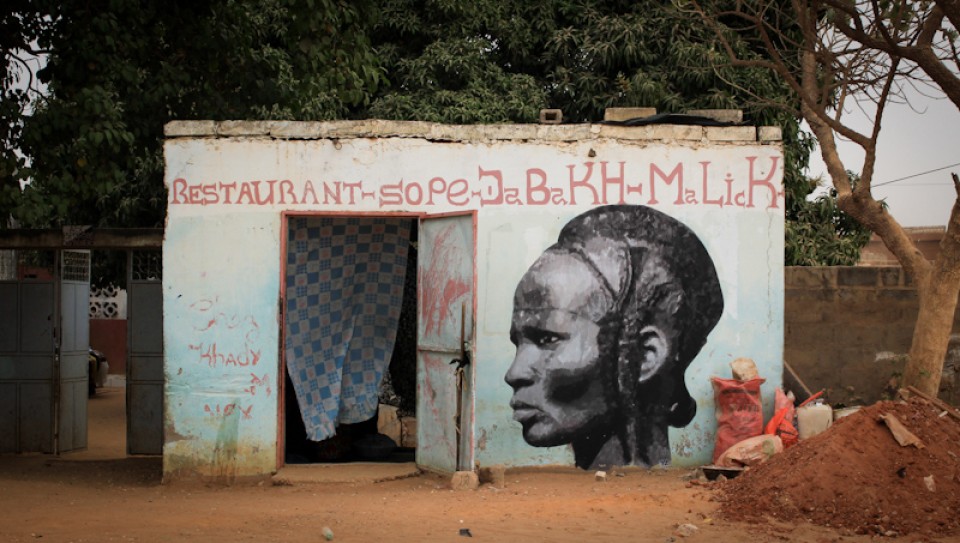

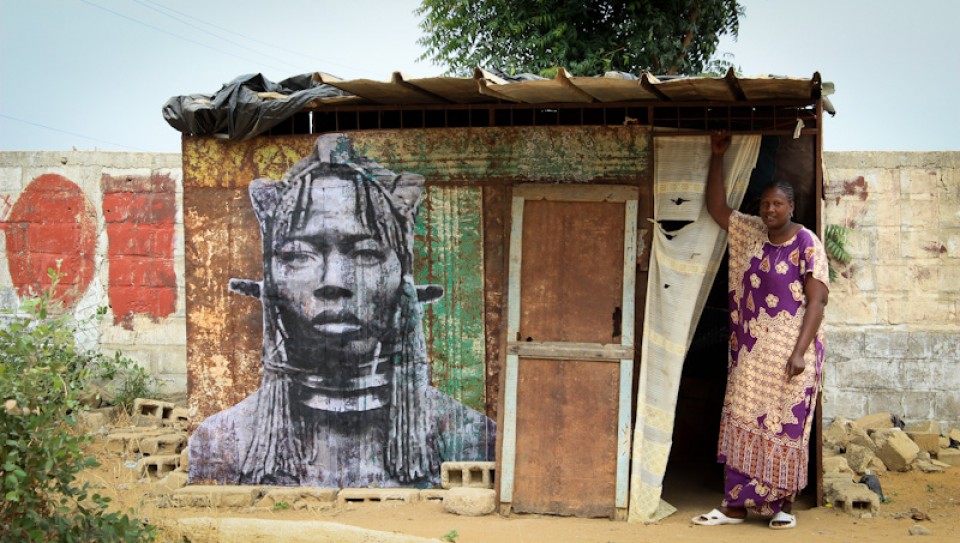

In 2015, a French street artist, YZ, begun her own campaign to pay tribute to the fierce female fighters of the 19th century. Working in Senegal, south of Dakar, she pastes large-format photograph prints she found in local archives of the warrior women. You can see more of her installations here.

While they were also said to be the most feared women to walk the earth, they would also change how women were seen and respected in Africa and beyond.