Did you hear the one about the Soviet school children who presented a US Ambassador with a wooden plaque of the Seal of the United States as a gesture of friendship in 1945? It hung in his Moscow office for 7 years before discovering it contained a listening device. True story.

Man, that’s cold! Get it? Anyway, after discovering the bug, they called it “The Thing”, because it was the kind of technology which was borderline sci-fi for its time. One of the first covert listening devices to use remote technology to transmit an audio signal, the device didn’t have a battery and was both activated and powered from a remote source outside the embassy. Allegedly holes were drilled under the beak of the eagle to allow sound waves to reach the membrane.

It was discovered accidentally by a radio operator at the British embassy who began overhearing American conversations on an open radio channel as the Russians were beaming radio waves at the embassy of their World War II ally.

State Department employees were sent to Moscow in 1951 to investigate and conducted sweeps of the American, as well as the British and Canadian embassies, also suspected of being bugged. During this sweep, they found the Great Seal Bug, a.k.a The Thing.

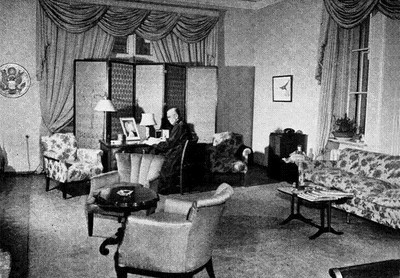

The Great Seal bug before its detection, visible to the left on the office wall beyond the Ambassador’s desk.

The CIA then hired a British scientist to run an investigation on the bug, which had an extremely thin membrane, and had actually been damaged during handling by the Americans, who were bewildered by the device. The British scientist’s examination of “The Thing” would later lead to the development of a similar British listening system used throughout the 1950s by the British, Americans, Canadians and Australians.

A replica of the Great Seal which contained the Soviet bugging device, on display at the NSA’s National Cryptologic Museum.

In 1960, at the United Nations Security Council, the Soviet Union confronted the United States about a spy plane which had entered Russian territory and been shot down (you might remember it being heavily referenced in the recent Tom Hanks film Bridge of Spies). In response to the accusation, the U.S. ambassador essentially proceeded to give a show & tell of the bugging device they had found in the Great Seal gifted to them by the Young Pioneer organization of the Soviet Union. The ambassador successfully pointed out, that it takes two to tango.

You can see the ambassador giving a live demonstration of the listening device in the seal in this archive news reel below…

The summit was subsequently aborted.

It’s quite the story, right? And yet it’s only half of an even more intriguing tale– that of the inventor behind the bug which managed to go undetected for seven years in the US embassy. But hang on a minute. Shouldn’t the US Ambassador’s office have been regularly swept for bugs even back in 1945?

The Thing was very difficult to detect. Like I mentioned, the technology was borderline sci-fi for its time; extremely small with no power supply, unlimited operational life and no radiated signals. It was made by a somewhat tragic Russian genius, Léon Theremin, who as a high schooler had built a million-volt Tesla coil and by the 1920s was working on wireless television, demonstrating moving images by 1927.

He was most famous for a pretty cool invention, the self-titled theremin, one of the first electronic musical instruments. The first to be mass-produced, it’s a very strange but beautiful instrument which involves using a magnetic field to control the pitch in one hand and the volume with the other.

You can see him in action with his theremin below, which even today, seems like something in between sci-fi and hocus pocus.

Léon toured the world’s concert halls, performing in Europe and then the United States at Carnegie Hall and the New York Philharmonic. He set up a laboratory in New York in the 1930s and his mentors included composer Joseph Schillingerand physicist (and amateur violinist) Albert Einstein. He married a young African-American prima ballerina of the first American Negro Ballet Company, Lavinia Williams, which shocked his social circles.

So here Léon was, enjoying life with his sci-fi musical instruments, giving the town something to talk about, when suddenly, he disappears.

Lavinia said he’d been kidnapped from his studios by some Russians. In 1938, he shows up in the Soviet Union, citing tax and financial difficulties in the United States as his reasons for returning so abruptly. Shortly after his return, Léon was arrested and sent to work in the far east Russian gold mines. For a while, he went missing again, rumoured to be dead, but the inventor had been sent to the Gulag camp system to work in a secret laboratory.

There, he was put in charge of a team of workers to create eavesdropping systems for the USSR. He created one call the Buran system which the head of secret police used to spy on the British, French and US embassies in Moscow and allegedly, even on Stalin. It’s said Theremin actually kept some of the tapes in his room. In 1947, Theremin was awarded the Stalin prize for inventing this advance in Soviet espionage technology and shortly after, Léon invented The Thing.

Léon Theremin

The same year, he was released from the gulag and “volunteered” to remain with the KGB for another 20 years. When he finally got back to his music working at the Moscow Conservatory of Music, the chief music critic for The New York Times wrote a glowing article on Theremin’s work. Shortly after the piece was published in the US publication, the Conservatory’s Managing Director declared that “electricity is not good for music; electricity is to be used for electrocution” and had all Léon’s instruments removed and banned from the Conservatory. They fired him too.

There’s so much more to Theremin’s fascinating life, which you can get a taste of on his Wikipedia page, but boy does someone need to make a movie about this guy.