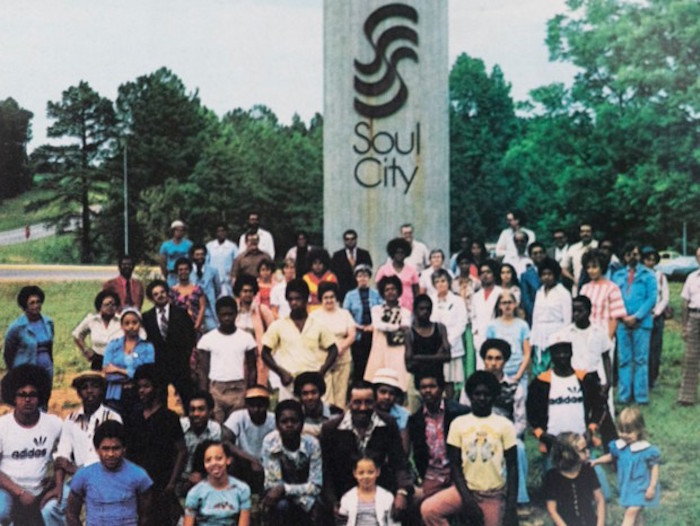

In the heart of what was North Carolina’s old tobacco and cotton-field industry, lies the remains of Soul City, an unrealised utopia born in the midst of America’s 1970s urban crisis, intended to encourage black empowerment in a new all-African American planned community. Bankrolled by Nixon’s Republican government, “built by black people and for black people”, Soul City was projected to have 44,000 inhabitants by the year 2004. As you’re about to see from photographs of the half-empty town, things didn’t exactly go as planned…

The dream died when Soul City filed for bankruptcy in 1979. Housing units, a health clinic, fire station, small commercial businesses, sporting facilities, a church, the region’s first real water system and sewage infrastructure had all already been built. A newly mobilized political base had been established but there were less than 150 people actually living in the city.

The community had failed in reaching its planned growth targets and in the years following its foreclosure, the Soul City became a ghost town.

Many of the small businesses were and still are deserted, a few residents occasionally use the abandoned fire house for cookouts and there are miles of roads going nowhere.

The model community is a distant memory, now officially an incorporated part of Warren County. While the dwindling population has improved over the years, Soul City is certainly lacking a thriving and empowered black community it set out to attract.

To add insult to injury, the one industrial building, known as “Soul Tech 1”, designed to be an incubator for new business steered by African American interests, was purchased by the Warren County Correctional Institution in 1993. Prison labourers now make janitorial products there for $3 a day.

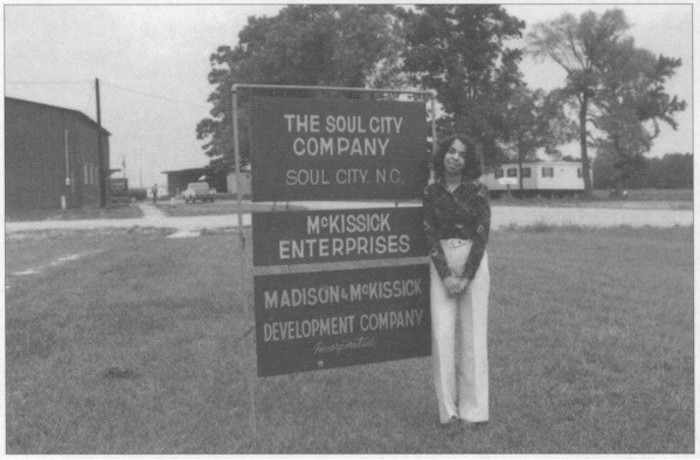

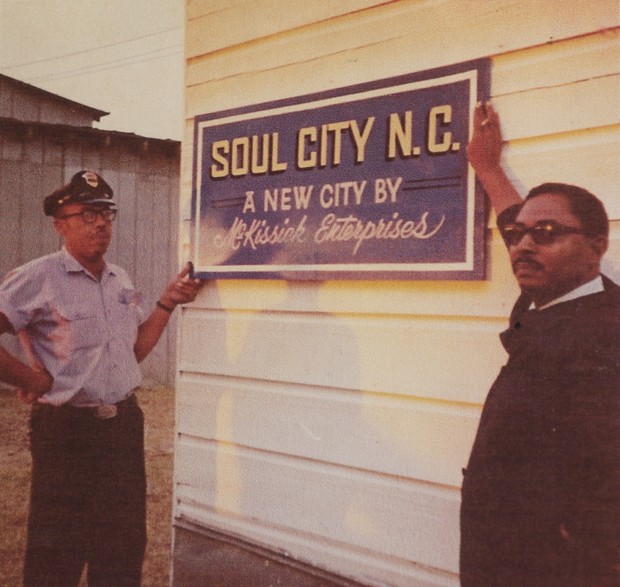

Soul City’s founder, an early leader in the civil rights movement, Floyd McKissick, is probably rolling over in his grave. He first pitched the idea for his all-black town in 1969 when the Black Power movement was reaching its peak in the United States. He believed African Americans should own and run their own capitalist organisations, free of racism, and the only plausible way to do this was in a situation where the black community outnumbered the white population.

President Nixon liked capitalism of course, and he liked the idea of black capitalism too. In 1972, the city received a grant of $14 million based on plans of attracting industry and developing residential housing (as well as the alleged promise of McKissick’s endorsement in Nixon’s 1972 presidential election).

The press however, challenged McKissick on the ideas behind Soul City, accusing him of encouraging a trend towards separatism and taking steps backwards from integration. McKissick’s response was to suggest Soul City was no different from what the Chinese communities had in Chinatowns within cities across the world.

Soul City, however, was to be America’s first free-standing community built for African Americans (though not exclusively) out in a rural setting and separate from any other municipalities. In the late 1960s, the Black Power Movement had begun to diverge and the general feeling was that the time for idealism was over.

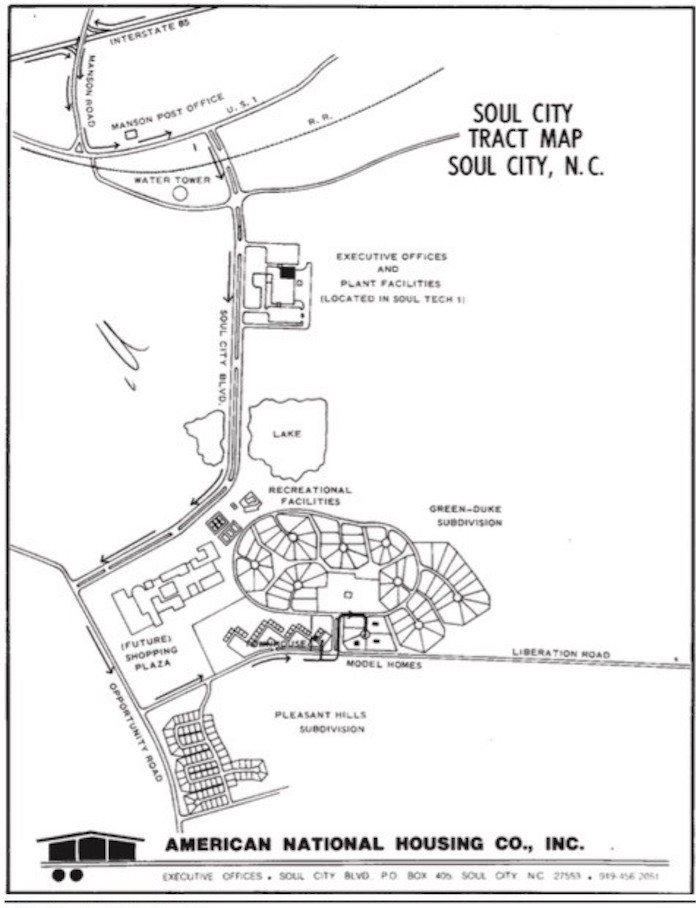

Soul City was built from the ground up on 3,600 acres of land where 59 slaves had once worked on an old tobacco plantation. Warren County was known as one of the most destitute counties in the state, a hot bed for Ku Klux Klan activity, and while African Americans made up more than 60 percent of the population in the area, all their elected officials were white. That McKissick was even able to get as far as he did with Soul City was an achievement in itself.

It was time for African Americans to claim their piece of the American dream. The community placed emphasis on providing jobs and opportunities for minorities and the poor, with mixed income housing. You can find the original pamphlet which explains a lot of the hopes for Soul City here.

McKissick envisioned Soul City as a community where all races could live in harmony, organized by African-American businesses. The roads today still have names like “Liberation,” “Freedom,” and “Soul City.” One street is even called White Street and another Brown.

There was a 30 year plan to reach over 18,000 residents by 1989 and over 40,000 residents by 2004 but in reality, only 150 people were living in Soul City when bankruptcy was filed in ’79.

A lot of things went wrong for Soul City. There were plenty of racist elected officials still around scaring off corporations from locating there, as well as a looming economic slump. The press held nothing back in going after McKissick’s planned community, publishing numerous articles accusing Soul City of political payoffs, nepotism and financial misappropriation which resulted in lawsuits and investigations into the use of funds by the the city’s developers.

There were even swipes about Soul City’s name being “too black”. Without the industry, potential residents stayed away and without the residents, industry stayed away. Soul City failed to hit its targets and despite eventually being cleared by a Government Accountability Office audit, there was one more nail in the coffin to come…

The very same month the city foreclosed, Warren Country was notoriously selected by North Carolina as the site for dumping thousands of gallons of toxic waste into a landfill just feet away from the area’s local groundwater source. The untreated soil, tainted by the cancer-causing chemical compound, PBC, had previously been illegally dumped elsewhere in the state, and the state’s decision would finally cripple the community.

Any last-ditch efforts to attract new companies to save Soul City were foiled as a huge poison pit near the water supply was planned for the area. To the residents, it felt like racial discrimination; picking a site in a predominantly African-American and mostly poor county to dump hazardous waste. A report released in 1987, which analyzed location data on hundreds of hazardous waste sites around the nation, “revealed that these facilities were far more often situated near communities with large minority populations than communities with majority-white populations, even after controlling for income”.

When the trucks filled with toxic waste came down the road headed for Soul City in 1982, residents lay down in the street in an act of civil disobedience that marked the birth of the civil-rights-based environmental justice movement. Even Floydd McKissick himself was arrested during the protest, but the trucks could not be stopped from entering.

The federal government didn’t get around to cleaning up the PCBs in the soil until 2003, but it was far too late for Soul City by that point.

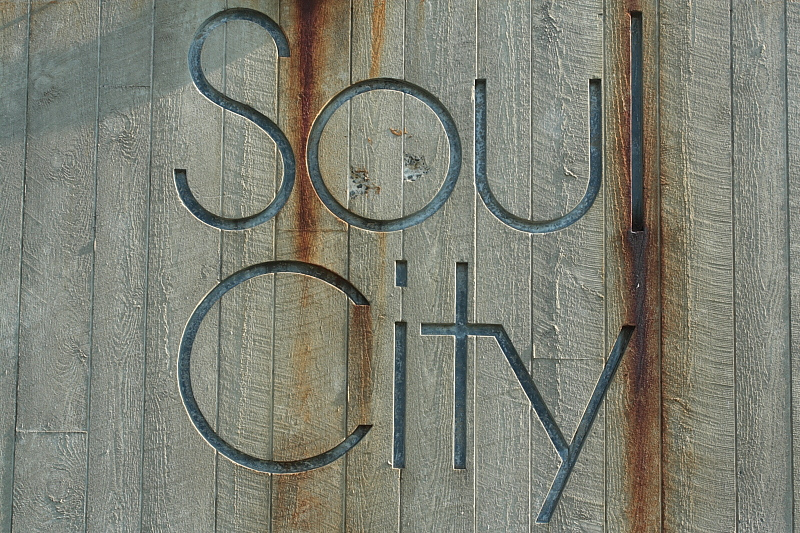

The rusting Soul City sign, with its unmistakable 1970s design, is still standing, albeit in a different spot in town, near an old historic building. A number of new homes have reportedly since been built by newcomers to the area and while the streets may be eerily empty, there’s clearly something salvageable in the community formerly known as Soul City.

With the present day ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement, could Soul City ever be an idea brought to the table again? Could this utopian ghost town ever see a revival?

Sources: City Lab, 99% Invisible, The Faculty Lounge.