There are some places in our cities that we’ll never get to see and the secret garden is one of the most endangered species in a modern metropolis. Lost in time, replaced to make room for new development or kept hidden from public view, these rare green sanctuaries can almost hold a mythical status in our urban lives.

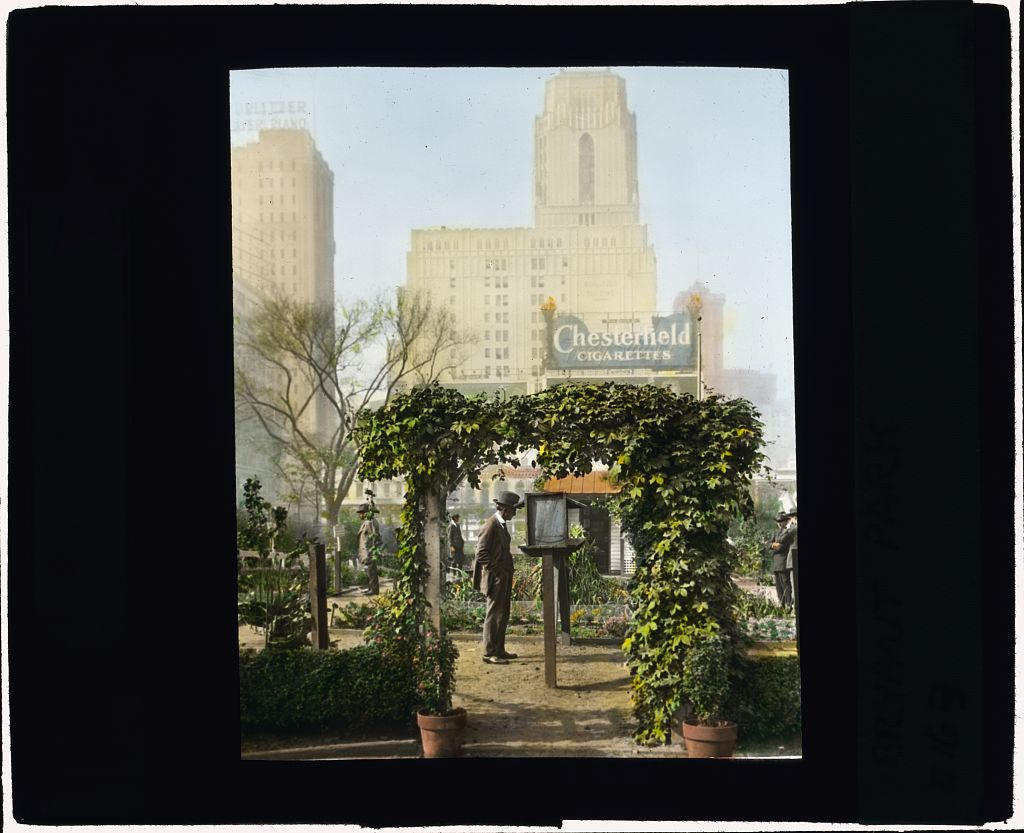

Demonstration garden, Bryant Park, 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue, New York, part of a WWI campaign, encouraging citizens to get more involved in food production, and utilize public spaces, fire escapes, and rooftops to grow their own produce. Located on the north side of the park, about where the ping pong tables and Reading Room are now.

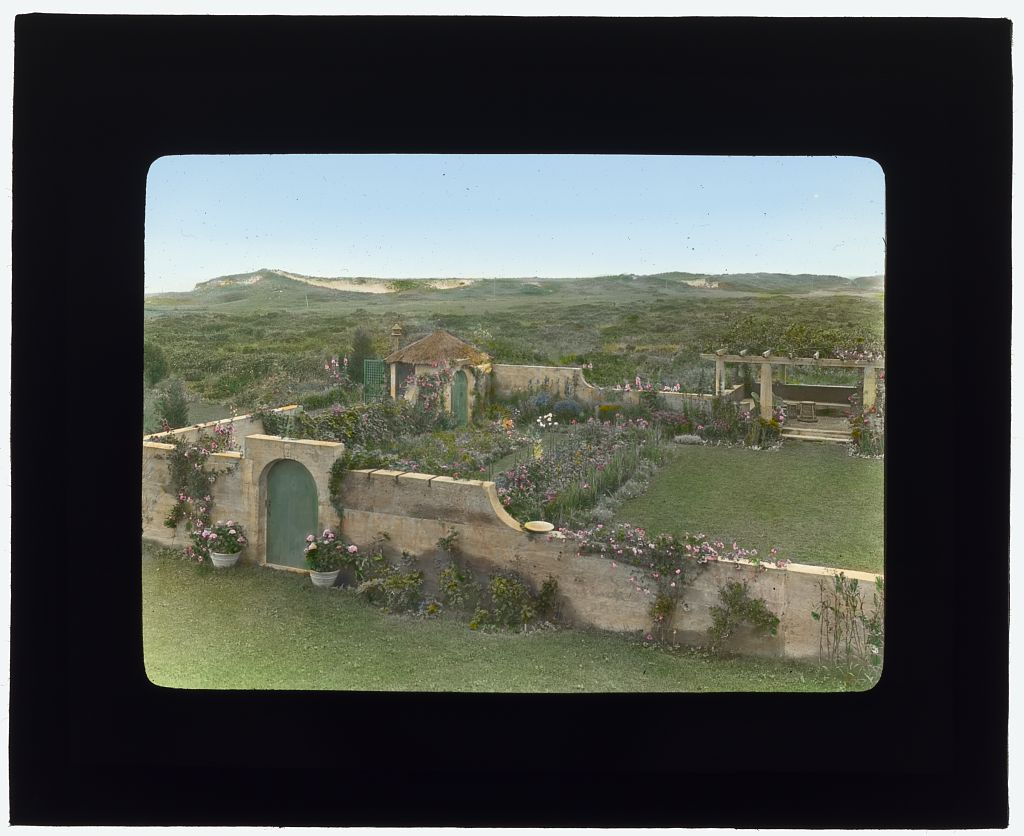

Today, I felt like I opened a box of lost treasures in the digital archives of the Library of Congress when I stumbled upon nearly 700 hand-colored glass lantern slides of truly exquisite gardens, taken around the 1920s across America and also in Italy, France and England. The collection is a dream to discover in its entirety, but the slides that interested me the most, were the ones that unlocked the secret and old world gardens of a bygone New York City…

“Flagstones,” Charles Clinton Marshall house, 117 East 55th Street, New York, New York. Tea house/sleeping porch

These slides were taken by Frances “Fannie” Benjamin Johnston, one of the earliest pioneering American female photographers and photojournalists, but there’s a good chance you’ve never heard of her. Art institutions didn’t take much notice of garden photography during Frances’ lifetime and it was a struggled just to get her name published in garden magazines of the day. Born into a wealthy family, she was well connected in elite society, and had more luck being commissioned to do celebrity studio portraiture, photographing the likes of Mark Twain and Alice Roosevelt. But Johnston had an increasing interest in photographing architectural sites and gardens, even though ironically, she never planted a garden of her own until she was in her 80s.

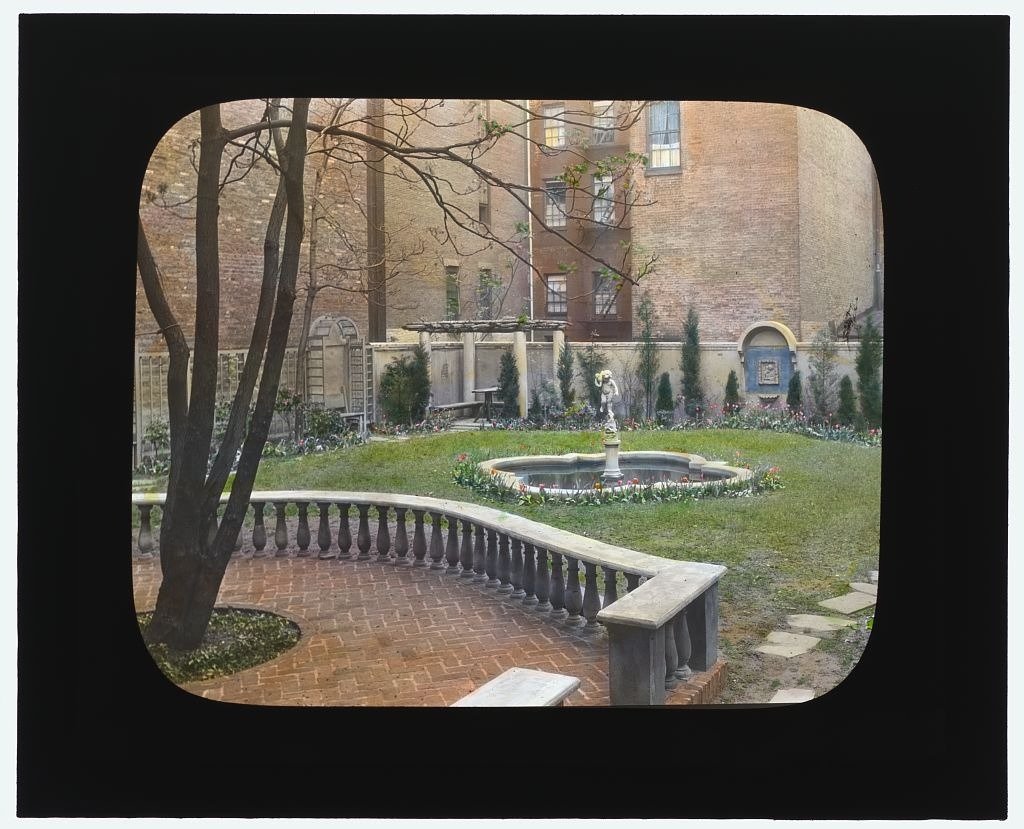

Charlotte Hunnewell Sorchan house, Turtle Bay Gardens, 228 East 48 Street, New York, New York

When she died, Frances left most of her uncelebrated collection with the Library of Congress; over 20,000 prints documenting the most beautiful backyards across American and Europe, overlooked in the archives for decades.

Turtle Bay Gardens, 227-247 East 48 Street and 228-46 East 49 Street, New York, New York View east to common garden.

Frances had travelled the world, advertising her photographic services and finding her way inside some of the most lavish secret gardens of the era, a unique experience she wanted to share with as much realism as possible. Having her slides hand-painted to recreate the lush colours was a start, but Frances wanted to try new mediums and experiment with moving pictures. Despite her best efforts, she was never able to take it to the next level and film her garden visits.

Turtle Bay Gardens, 227-47 East 48th Street and 242-46 East 49th Street, New York, New York. Pergola in common garden

Even if we can’t move with Frances through these gardens behind her camera, the near-spiritual experience she must have felt in discovering them, is still very much present in her slides. Perhaps the most ethereal of her New York slides are the ones taken in Turtle Bay Gardens, a space that actually still exists today, but very few New Yorkers have ever had the privilege of seeing with their own eyes.

Charlotte Hunnewell Sorchan house, Turtle Bay Gardens, 228 East 49th Street, New York, New York.

Turtle Bay Gardens was the brainchild of an American heiress, Charlotte Martin, who bought 20 dilapidated townhouses in 1919 and re-modeled them, creating a shared a great common garden between them, featuring a copy of the fountain in the Villa Medici.

Many famous residents, including Hollywood icon Katharine Hepburn and Bob Dylan have owned homes which comes with private access to the historic gardens and these properties are now among the most expensive and exclusive in New York City. While the Turtle Bay Gardens have been protected by covenants and agreements set in place by Mrs. Martin, they have seen changes over the decades; rules have been bended, property restrictions have lapsed, plots altered slightly. But since we’d have to pay a pretty penny to ever see inside, or have some seriously good contacts, we’ll probably never know how much the gardens have been changed or unchanged.

Turtle Bay Gardens, 227-47 East 48 Street and 242-46 East 49 Street, New York, New York.

But Johnston didn’t only just point her camera at the backyards of New York’s wealthiest and her work’s diversity often revealed the stark class divisions of the roaring twenties…

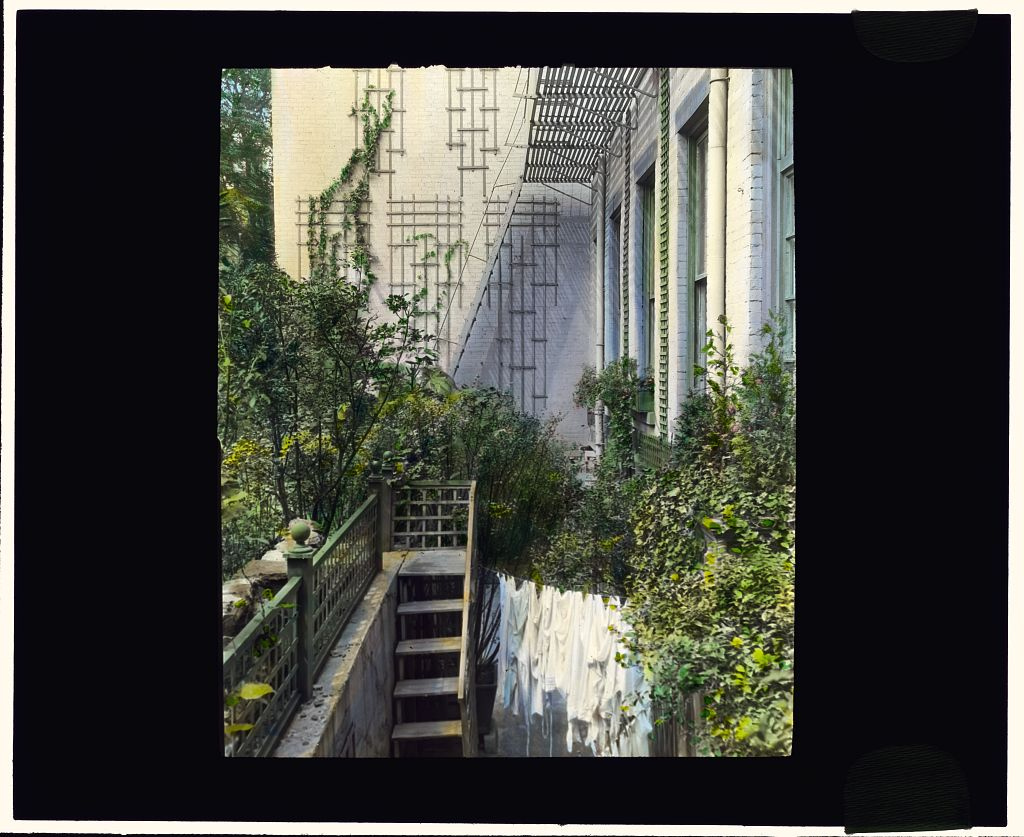

“Flagstones,” Charles Clinton Marshall house, 117 West 55th Street, New York, New York. Laundry on clothesline.

Take this next slide of an East 30th street brownstone, labelled by a researcher at the Library of Congress as “Janitor apartment”…

Janitor’s apartment, 137 East 30th Street, New York, New York. Stairwell garden.

According to the Smithsonian, who spoke to the researcher Kristina Borrman, this photograph was included in a WWI-era exhibition for city gardens. Borrman learned the janitor was actually awarded a prize as part of the New York City Garden Club’s effort to encourage all citizens to garden with what little space and resources they had. “He was awarded this prize at the very same exhibit [where] someone who bought tenement buildings at Turtle Bay and recreated a backyard space and created this beautiful garden, was also given a prize. So someone that had kicked out these poor people of their homes was awarded a prize in the same space as this janitor.”

Studio Italiano store, 638 Lexington Avenue, New York, New York. Entrance garden

Vivian Spencer townhouse, West 12th Street, New York, New York. Birdbath on lawn.

Dr. Henry Alexander Murray, Jr., house, view to terrace, 129 East 69th Street, New York, New York.

Unidentified city garden, probably New York, New York.

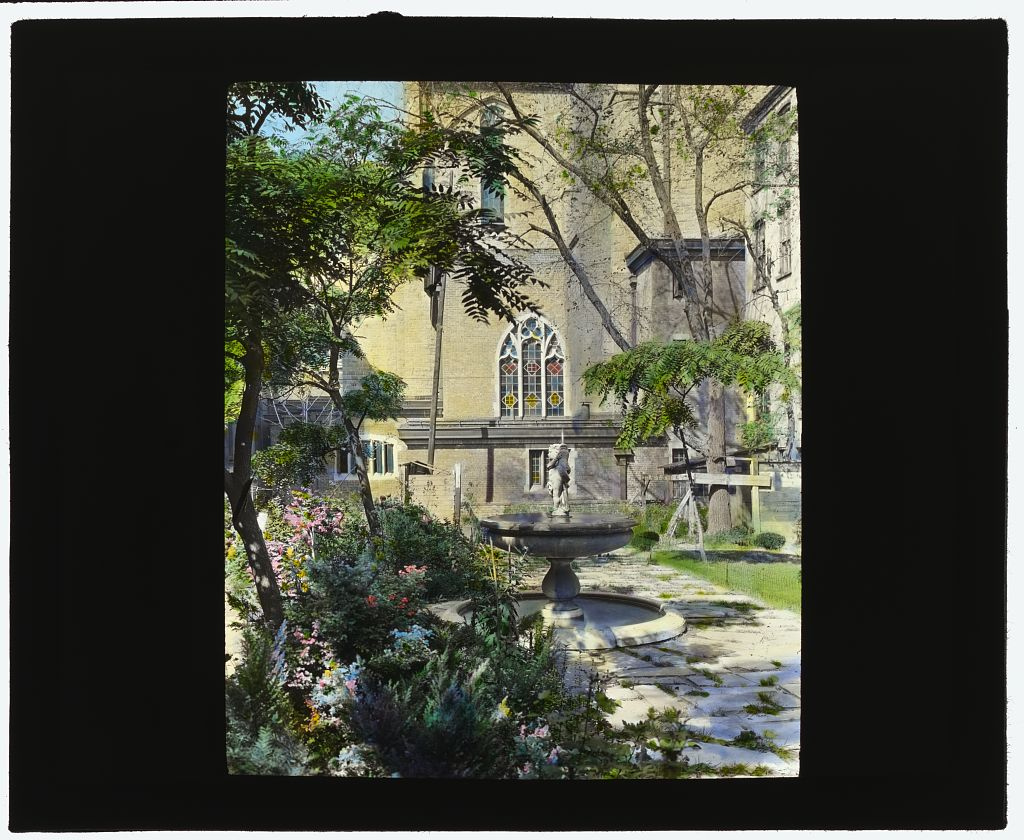

“Jones Wood” townhouses, East 65th and East 66th Streets between Lexington and Third Avenues, New York, New York. View from garden to St. Vincent Ferrer church.

“Jones Wood” townhouses, North terrace fountain.

“Jones Wood” townhouses, reflecting pool on south terrace.

Jones Wood Garden is another of New York’s exclusive secret gardens where the only way to have access is to own one of the surrounding townhouses which as of last year are going for upwards of $11 million. It was established in 1920 by a group led by architect Edward Shepard Hewitt, right around the time Johnston photographed it.

Twelve homes were purchased by Hewitt and had a 100-by-108-foot sunken garden planted to resemble a country estate. It became the Jones Wood Association in the 1950s and each of the townhouses now have private areas for entertaining and dining.

The New York Times covered for of the house sales here and took a few photographs of the gardens today.

George Hoadly Ingalls house, 154 East 78th Street, New York, New York.

Unidentified backyard garden, probably in New York, New York.

Laura Stafford Stewart house, 205 West 13th Street, New York, New York. Terrace

Unidentified townhouse garden, probably in New York, New York.

George Hoadly Ingalls house, 154 East 78 Street, New York, New York.

The Touchstone Garden, 118-120 East 30th Street, New York, New York.

Stairway to an unidentified city garden, New York, New York.

If you think you know any of the unidentified gardens, please do have a go at solving the mystery in the comments.

In the meantime, I highly recommend discovering some of the jaw-dropping lost gardens the rest of America and Europe had to offer Frances Benjamin Johnston’s camera lens.