Sex and botany– two words rarely found in the same sentence, but there was a time when the study of botany was considered so obscene that books on the subject were censored for women; branded dangerous and unsuitable for her delicate sensibilities. Gardens and greenhouses became an enlightened woman’s secret haven of discovery, expression and temptation. While today’s scientific world might have lost sight of the romance, once upon a time, botany was the most provocative and desirable virtuosity of the enlightenment era. And we’re about to discover how the fashion world is bringing it all back…

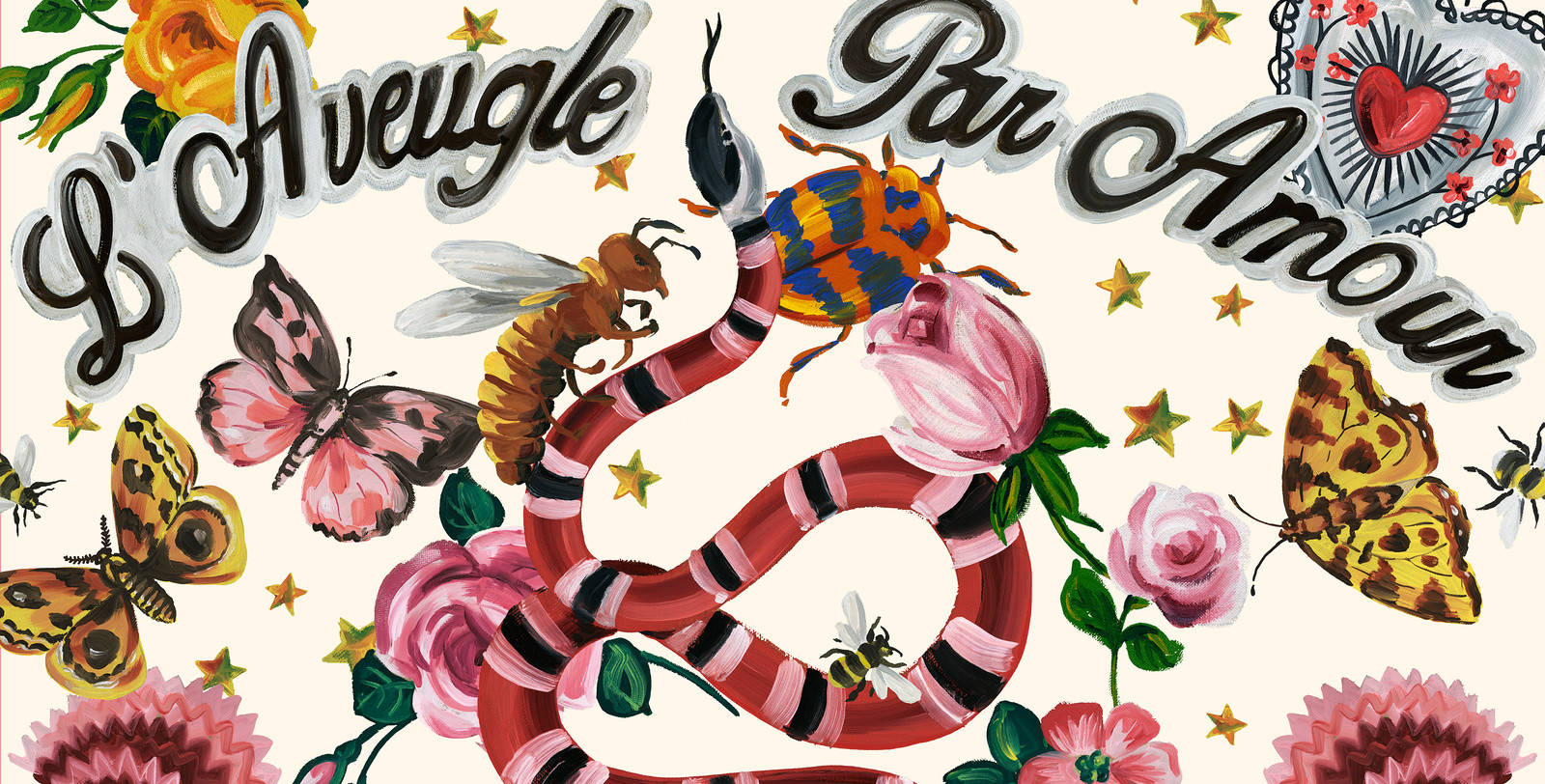

So what could possibly be so sexy about botany? I was asking the very same question a few days ago when legendary Italian fashion house, Gucci, approached me to explore the story.

Creative director Alessandro Michele has just revealed a magical collection inspired by the nostalgia of secret gardens, forgotten in time. His patterns resembling antique botanical illustrations were like clues that led me down the rabbit hole of this lost world…

(c) Extinct Flightless Bird

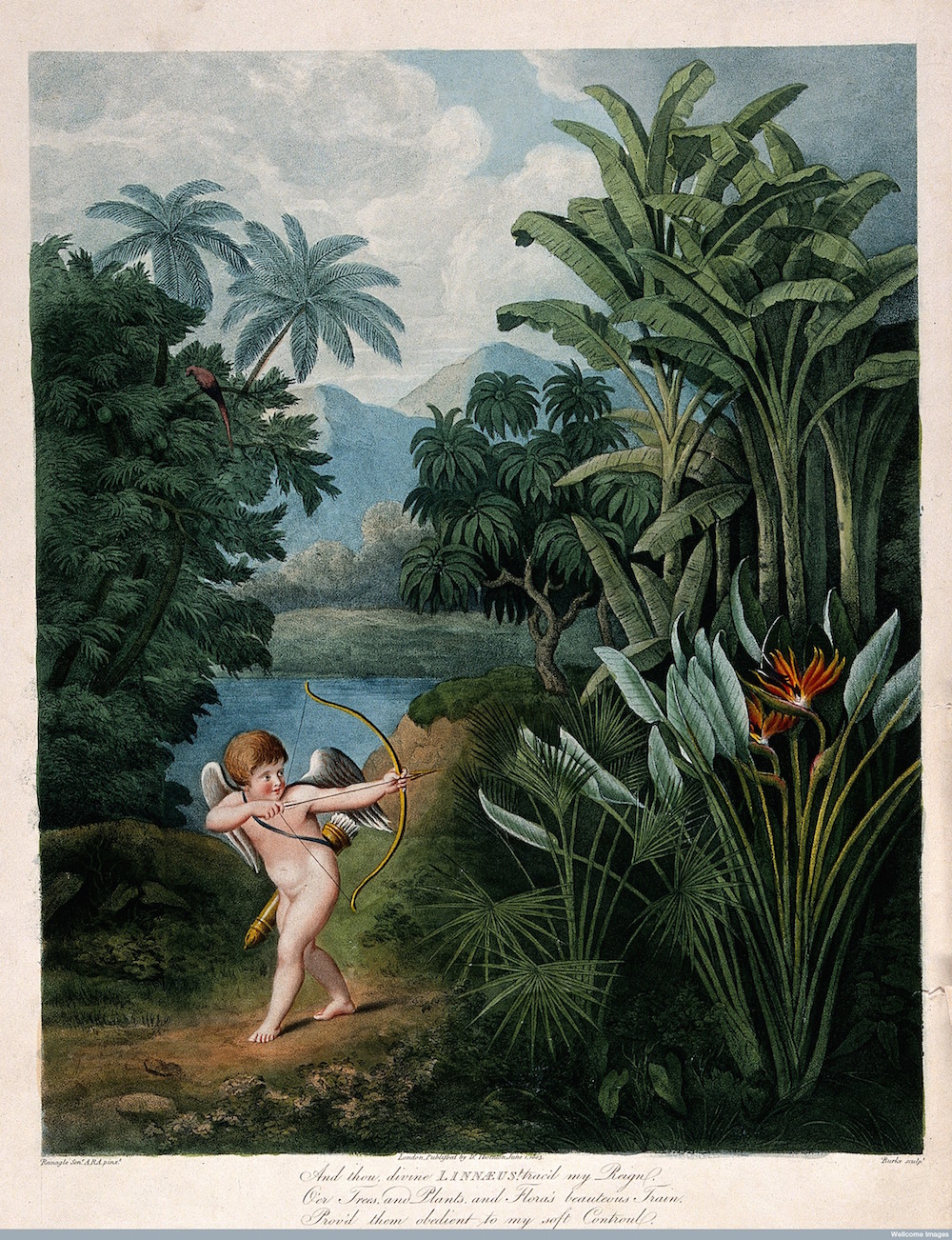

In the 18th century, a new wave of Enlightenment botanists were sexing up the study of plants, going as far as to juxtapose our own reproductive systems with plant anatomy, comparing the stamen to a man’s phallus, the style to a woman’s intimates, even the plant petals to a bed and the leaves to the bedroom curtains.

Flora at play with Cupid – The Loves of Plants, Erasmus Darwin’sThe Botanic Garden (1789), Wellcome Library

Carl Linnaeus, the great Swedish botanist, identified pollen as the impregnating male sperm that could be carried “promiscuously” in the wind. He described female plants as either virginal or promiscuous flowers that exude a seductive scent when they’re ready to mate, triggering the birds, bees and butterflies to join in on celebrating her nuptial rites.

(c) The British Library

Such libertine and sexualized ideas shocked conservative society who labelled it “loathsome harlotry” and something that “the Creator of the vegetable kingdom” would never have allowed. The rest of society however, was fascinated.

(c) Smithsonian

Inspired by Linnaean’s controversial teachings, Charles Darwin’s grandfather, Erasmus, wrote The Loves of the Plants, a poem which brought botany to the masses, making it interesting and relatable. This poem served as many a young lady’s guide to discovering her own sexuality (and man’s). Darwin revisited comparisons of plant reproduction and wedding nuptials, capturing the imagination of curious and impressionable young women awaiting marriage. While simultaneously raising anxiety surrounding female modesty, botany emerged as one of the most intriguing topics of the Enlightenment.

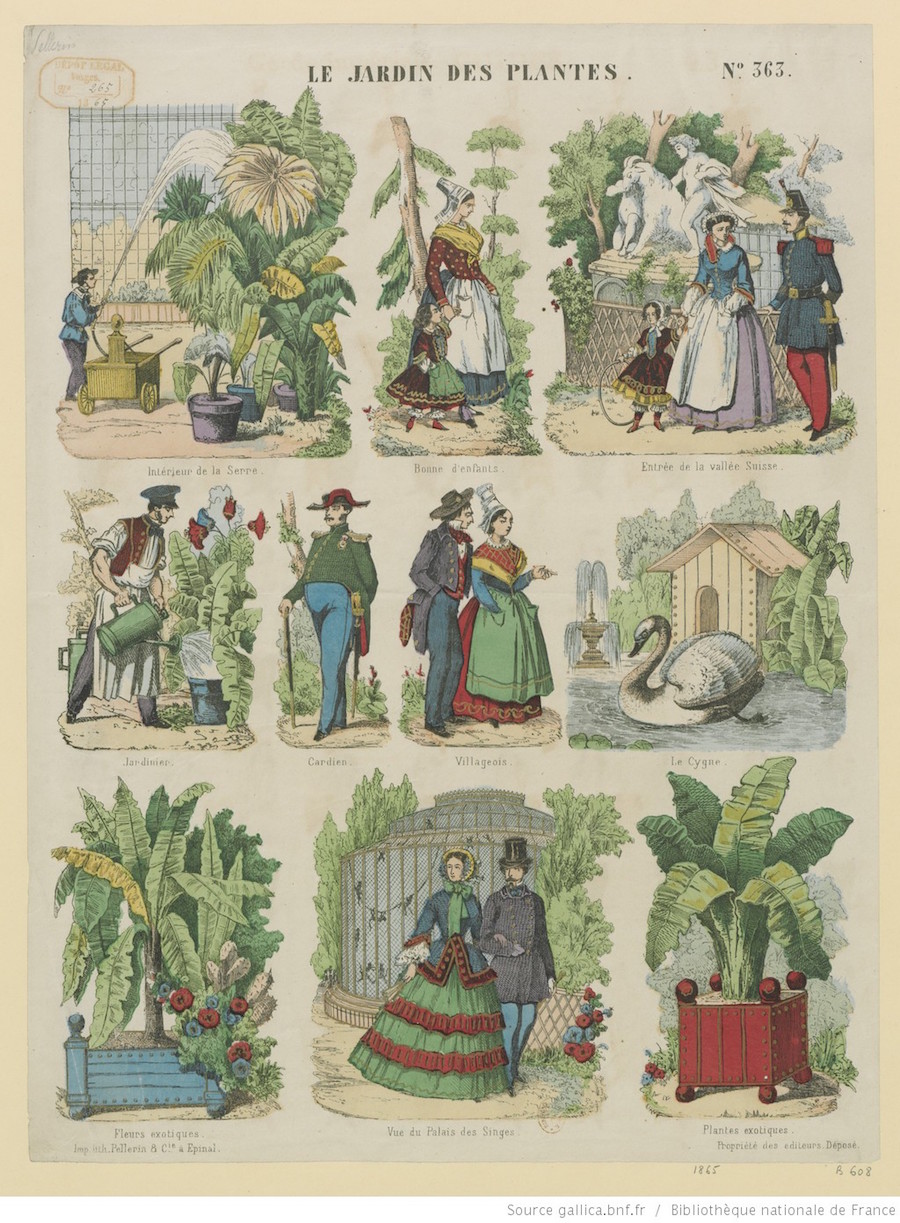

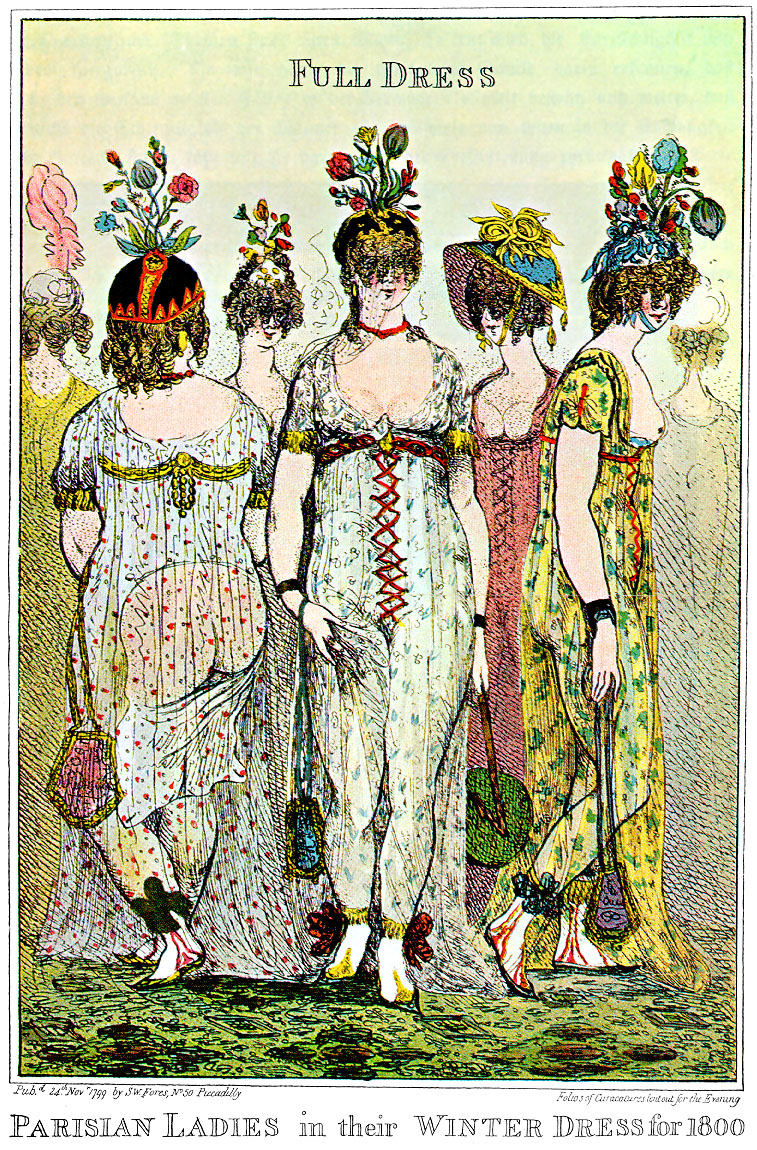

Queens and Princesses were instructed in botanical illustration and plant collecting became a highly desirable pastime, encouraged by fashionable ladies magazines and periodicals. Women’s clothing began reflecting the romantic science and floral designs dominated fabrics and silks of the 18th century. The greenhouse even became her beauty boudoir where she could pick out accessories for a growing fad in hair styles that incorporated anything from fruits, shells and artificial birds into her coiffure.

(c) The Met Museum, engraving by Matthew Darley circa 1777

An English philanthropist of the day, Hannah More wrote, “I hardly do them justice when I pronounce that they had, amongst them, on their heads, an acre and a half of shrubbery … grass plots, tulip beds, clumps of peonies, kitchen gardens, and greenhouses.”

A new stereotype of the sexually liberated bad girl botanist was born in the turbulent revolutionary climate of the 1790s. An innocent pastime for genteel ladies was suddenly brewing an indulgent and dangerous feminist movement that was making a male-driven society very uncomfortable. Religious leaders warned that botanising girls who showed interest in exploring the sexual parts of the flower, were “indulging in acts of wanton titillation”– (just the sort of thing to fuel any female libertine’s fire).

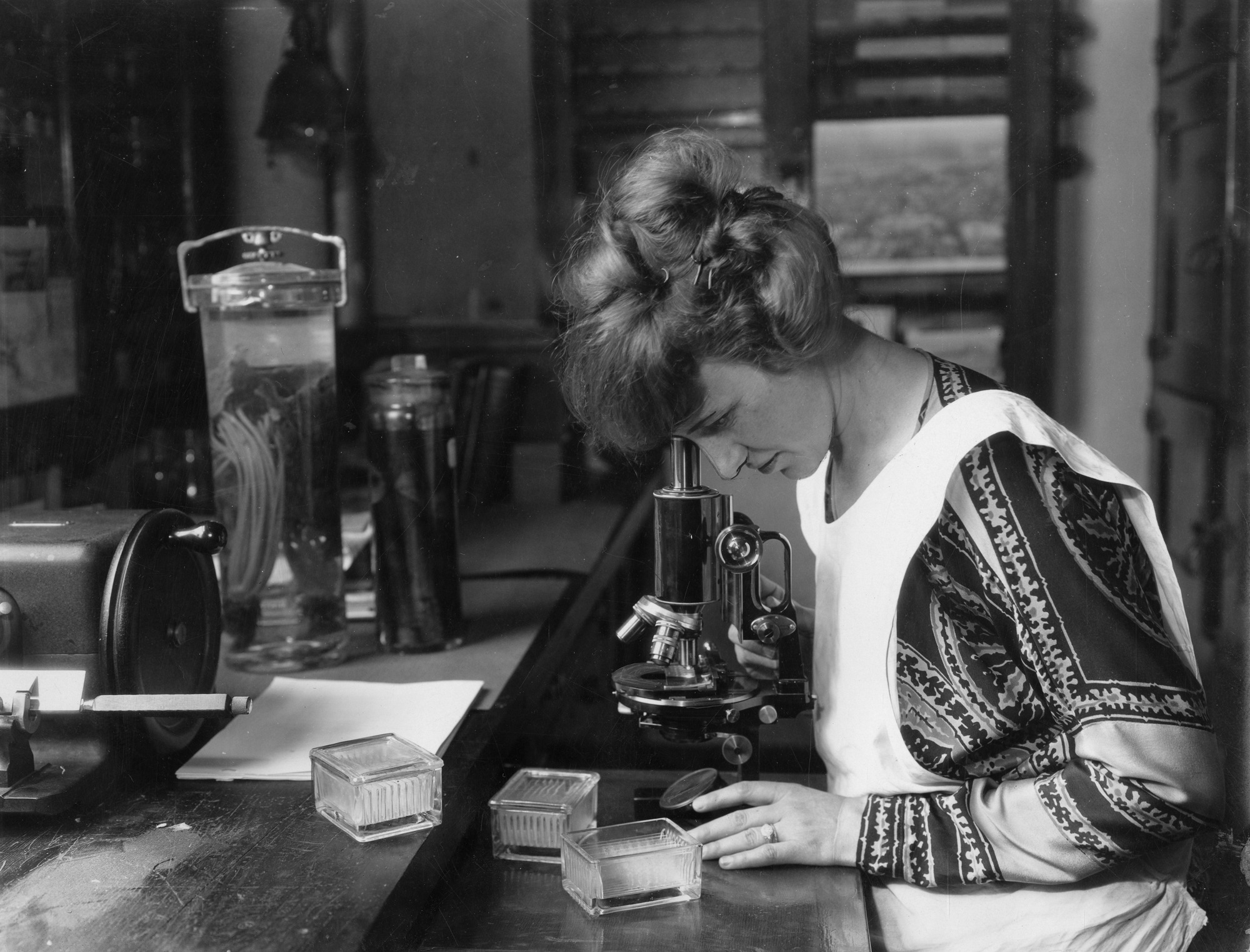

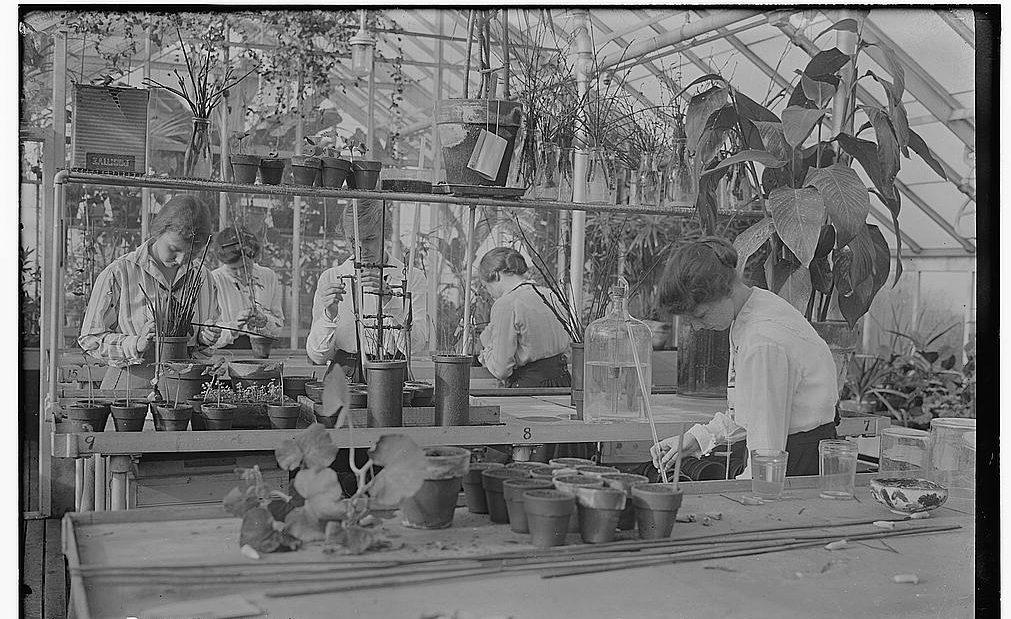

(c) Library of Congress

Conservative organisations didn’t like the direction that botany was heading and by the early 19th century, there was a strong counter movement underway to censor botanical textbooks for women. It was deemed improper for the female pen, effectively silencing their voice on the subject. Botany, as it was known in the enlightenment, became a lost and repressed passion for women … almost.

(c) Extinct Flightless Bird

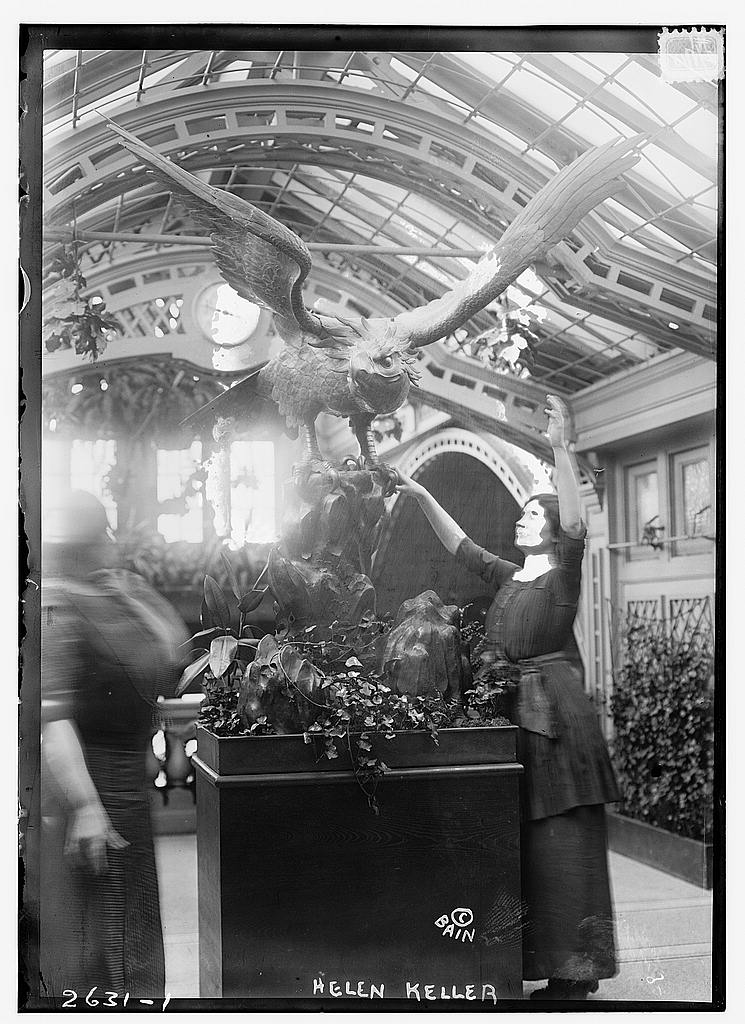

While the days of debating the Linnaean sexual system were over for women, I couldn’t help but notice that all this censorship was coinciding with the flourishing spiritualism movement in early Victorian society. The curiosity for the spirit world was particularly popular amongst educated liberal females who also supported other repressed causes such as women’s suffrage and the abolition of slavery.

Botanical gardens were closely linked with superstitious beliefs surrounding ‘exotic’ medicinal plants being introduced to the West by colonial explorers. The romantic era for botanical exploration brought stories of tribal medicine men and women and their healing powers.

(c) Johnny Joo

You might also recall a reading a little novel called “The Secret Garden“, written by a female writer in 1910 exploring the spiritual power of nature’s forgotten garden.

(c) Swedish National Heritage Board

In his Gucci capsule collection, Alessandro Michele has dreamt of the forgotten botanical garden, locked away inside a glass forest where something mysterious slithers through the ferns, wings are fluttering inside rose petals and there’s magic in the heavy, wet air…

“I have a deep interest toward nature,” says Alessandro. “I have a sort of an animist soul,” which is reflected more than ever in his collection. Reminiscent of the bygone art of botanical engravings, featuring flora and fauna symbols of nature’s life cycle, Gucci has transported me to an enchanting era in time when stars aligned to produce a wave of botanical romance and intrigue.