You might be ready to light up that Cuban cigar thanks to Obama or fill up your Instagram account with voguish snapshots from a Havana vacation, but even with the historic opening of diplomatic relations with the US, how will life in Cuba really change for Cubans? To get a real idea of the transition that lies ahead for Cubans emerging from their socialist time warp, there’s one thing in particular that might really hit home. It’s not the mid-century cars they drive around in or the crumbling colonial buildings they live in– for me it’s their local supermarkets or bodegas (if you can even call them that). Did you know that Cubans still live off a 50 year-old food rations system controlled by the government? Known as La Libreta, the system was set up shortly after the revolution when Fidel Castro took power in 1959, requiring Cuban families to bring their state-provided ration books with them every time they make a trip to the grocery store. It’s a socialist experiment out of time and to the Starbucks-consuming foreigner, it will seem absolutely bonkers.

Food ration books make me think of wartime in the 20th century. Correct me if I’m wrong but I don’t think we’ve seen them since World War II Europe. For the average Cuban however, it’s a constant part of daily life in 2016. The libreta ration booklet was introduced in 1962 by Che Guevara and entitles citizens to a basic ration of groceries such as rice, eggs and beans, which they can buy at their local bodega at 12% of the market value, amounting to less than $2 a month for their monthly rations. Doesn’t sound so bad right? Well sure, if you’re okay with an allowance of say– 5 eggs a month.

Here’s how it works. Each household ration book has a number, a list of family members and their dates of birth. What you’re allowed to buy depends on your age and your gender. For example, milk, can only be bought for children below the age of seven or for pregnant women and the elderly. (So your morning bowl of cornflakes is definitely out). The bodega clerk also keeps a book containing the information on each local household and the list of products he is allowed to sell them. A bodega clerk will know if there is or isn’t a child under seven or an elderly member of the household who needs milk. There are penalties for families not reporting any changes in the composition of the household, but you do get extra rations if it’s your birthday or your weddind day. Cakes, rum and beer.

Here’s how it works. Each household ration book has a number, a list of family members and their dates of birth. What you’re allowed to buy depends on your age and your gender. For example, milk, can only be bought for children below the age of seven or for pregnant women and the elderly. (So your morning bowl of cornflakes is definitely out). The bodega clerk also keeps a book containing the information on each local household and the list of products he is allowed to sell them. A bodega clerk will know if there is or isn’t a child under seven or an elderly member of the household who needs milk. There are penalties for families not reporting any changes in the composition of the household, but you do get extra rations if it’s your birthday or your weddind day. Cakes, rum and beer.

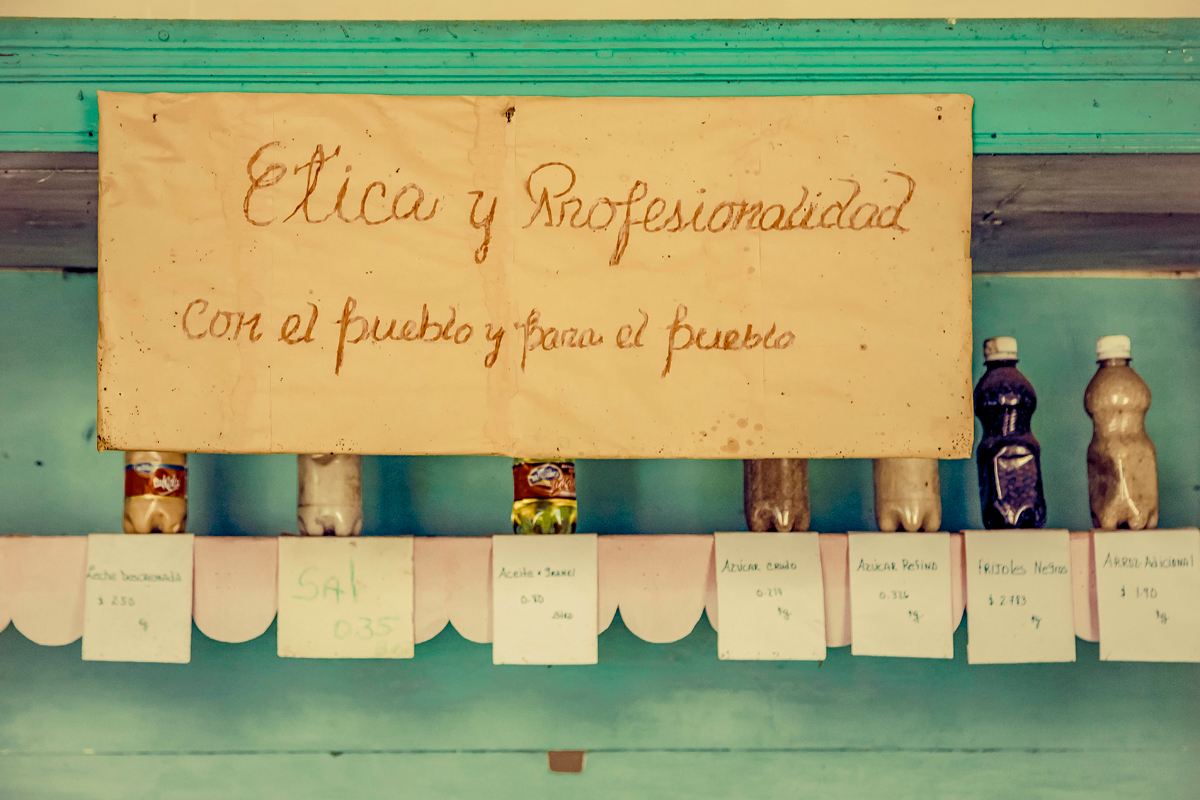

Any Westerner walking into a state-controlled bodega would find the shelves strangely empty compared to what we’re used to. Distribution and product delivery is often unreliable in a country that still needs to import about 80% of its food. Some months there can be a shortage of an entire food group and when products finally arrive at random, the bodega queues can be long and disorderly. When (and if) a weekly chicken ration arrives at the market, you can smell chicken cooking in every kitchen in the neighbourhood.

The Cuban bodegas you’re looking at here were captured by French photographer Francoise Guajour and while the colours and faces are beautiful, as images of food stores go, they leave me feeling like I skipped lunch.

The island’s ration allowance has been shrinking over the decades ever since it was introduced when American sanctions placed a sudden burden on the population. It was at its worst when the Soviet Union fell in 1991, known as “the skinny period”, el tiempo de los flacos, when Cuba’s food importation dropped by 75%. Rations were cut in half and the average citizen lost 20 lbs.

Things have improved since then, but still, this socialist experiment that costs the government over $1 billion annually, is barely enough to keep its people from starving and it certainly wouldn’t satisfy the average appetite.

But for the tourists of course, it’s very different. While finding beef in a state-run bodega is a laughable idea, for the foreigner paying in dollars at government-owned hotels, you can order as many hamburgers as you want. Beef is a pretty taboo subject for many Cubans, who haven’t tasted it since they were children.

Only state-owned luxury butchers can sell beef and serve it in their hotels and private restaurants. Did you hear the one about the cows in Cuba? Under Cuban law, a person can get more jail time for killing a cow than killing a human. Needless to say, there isn’t exactly an entrepreneurial spirit for farmers on this island.

If a local ever did feel like having a feast for dinner one night, there are options– if they have the money to burn. Products not freely available at the bodegas can be purchased at the mercado libre (free market), mercado paralelo (parallel market), or any supermarket that sells goods in convertible pesos (formerly known as dollar stores). And of course there’s always the black market. But at these establishments, market prices are so high, a kilo of milk powder for example, costs about $21. The average wage for Cubans is about $16 a month. Most food items that aren’t part of government rationing are simply off-limits to those who can only afford to pay in pesos.

Cubans who find jobs in the tourist sector have it easier with access to hard currency and those living abroad often bring back suitcases filled with milk powder to give to their families. But for now, la libreta and the bare-shelved bodega is still a lifesaver for the poor. When the reform-minded President Raul Castro proposed to eliminate the ration, he was met with overwhelming opposition, particularly from low-wage state workers struggling to get by on $15 a month.

Most Cubans have known the ration book all their life and see it as one of the main achievements of the revolution. As more tourists with a big appetite descend on the island however, it remains to be seen how this austere and archaic system will co-exist with the outside influence of an “all-you-can-eat” consumerism heading its way.

See more Cuban and urban photography by Francoise Gaujour on Behance.