The Nagakin Capsule Tower is one of the most important buildings in postwar architectural history in Japan, once praised as the ‘future of housing’, a rare remaining example of the Japanese Metabolism movement and the world’s first examples of capsule architecture built for permanent and practical use. It’s also a miracle it’s still standing after 40 years.

Lead image: Isamelsheimer.com

Sitting in the centre of Tokyo, the building has fallen into critical disrepair over the decades, and many would like to see it demolished, even capsule owners. As recorded in 2012, only 30 of the 140 capsules were being used as residences, while the rest were filled with storage or simply abandoned and left to deteriorate.

French photographer living in Japan, Jordy Meow found that some capsules have been so badly neglected they’ve begun to grown mini rainforests inside them. It’s ironically in line with the ideas of the Japanese Metabolism movement, which fused architectural megastructures with organic biological growth.

Personally, I’m digging the aesthetics of the Nagakin Tower, at least the inside of the building, which reminds me of a Hans Solo bachelor pad in a very retro Star Wars sort of way. It was built in 1972 by architect Kisho Kurokawa, composed of two interconnected concrete towers to which each capsule is connected by high-tension bolts.

The capsules were designed to be removable or replaceable, and were fitted with utilities before being shipped to the building site. Not a single unit has ever been replaced since the original construction.

Contrary to the ideas of the Marxist-influenced Metabolist movement, being able to take the capsules apart was not as easy as it was made out to be, and because of that, maintaining them and their materials over 40 years has proved rather difficult.

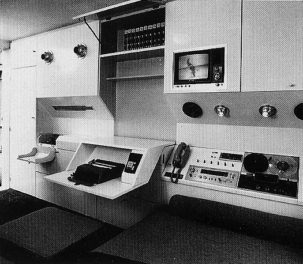

They measure in at 2.3 m by 2.1 m, originally marketed as living quarters for what is known in Japan as salarymen, which more or less refers to a white collar worker or businessman, typically a bachelor with a salary based income. At the height of the financial bubble, Japanese salarymen were known to work from 6am to 4am, and many of them lived far from work, needing a place in Tokyo during the week to briefly rest and freshen up. The compact capsules complete with kitchen amenities, a television set, a bathroom unit and a large circular window over the bed, seemed like the perfect solution.

But Nakagin Tower came too late. Even though it was the first design of its kind, it was one of the last for the Metabolist movement, which came to an end in the early 70s to make way for a new understanding of contemporary Japan. Nagakin was out of date before it was even built, an obsolete design surrounded by modern skyscrapers.

The oil crisis hit Japan in 1973 and by the time the financial bubble burst in the 2000s, even more capsules were abandoned, and materials that were not designed to stand the test of time were in very bad shape. Residents complained of squalid conditions, concerns over asbestos and huge temperature variations in the capsules due to a flawed ventilation system.

The same year that Nagakin’s “star architect”, Kurokawa, died in 2007, 80% of the capsule owners approved the building’s demolition to replace it with a much larger, more modern tower, but due to the recession, a developer was never found. In 2010, hot water to the building was shut off. There is almost zero maintenance on the rotting building and the few remaining residents (less than 40 people today) have to navigate leaky hallways to reach the communal shower on the entrance floor. Most recently, the building has been covered in a protective net because of reports of falling debris.

Still, there are many that believe the tower should be preserved as a cultural model of that era. Architecture critic for The New York Times, Nicolai Ouroussoff, described Nakagin as “gorgeous architecture; like all great buildings, it is the crystallization of a far-reaching cultural ideal. Its existence also stands as a powerful reminder of paths not taken, of the possibility of worlds shaped by different sets of values.”

The tower is certainly of interest with curious and snap-happy foreigners, and amazingly– the cost of the capsules seems to have risen, even doubles in the last 2-3 years according to this interview with one of the capsule owners.

Jordy Meow, the French photographer who became fascinated with the decaying building that he passed every day on his way to work, befriended Maeda-san, who has been buying up decaying Nakagin capsules and renovating them (he now owns 13 of the 140 capsules). He told Jordy that where a few years ago you could buy one for around 34,000 euros, the prices are now between 50-80,000 euros.

You can see some of the before & after renovations undertaken byMaeda-san here.

This year, photographer Noritaka Minami published 1972, a photo book of the decaying tower.

At 44 years-old, Nakagin is only six years away from being considered for protection. In the Japanese system for the protection of cultural properties, there is an unwritten rule that says only buildings older than 50 years old can be considered. The thought behind this unwritten rule is that if a building can exist more than 50 years by itself and is still appreciated, then its historic value can be acknowledged. But can it make it another six years? Would you want it to?