If you were living in Paris during the years that followed World War II and liked to party, you’d better have known Boris Vian. In 1950, he wrote the original guidebook to bohemian Paris and pioneered a movement which brought back the city’s “joie de vivre” that had been lost during the German occupation. Along with Jean Paul-Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Boris symbolised intellectual café society in post-war Saint Germain and became the leading promoter of American jazz music in France. His connections to the intellectual movements and nightlife of the Parisian Latin Quarter earned him the titles “Prince of Saint Germain” and “Prince of caves”.

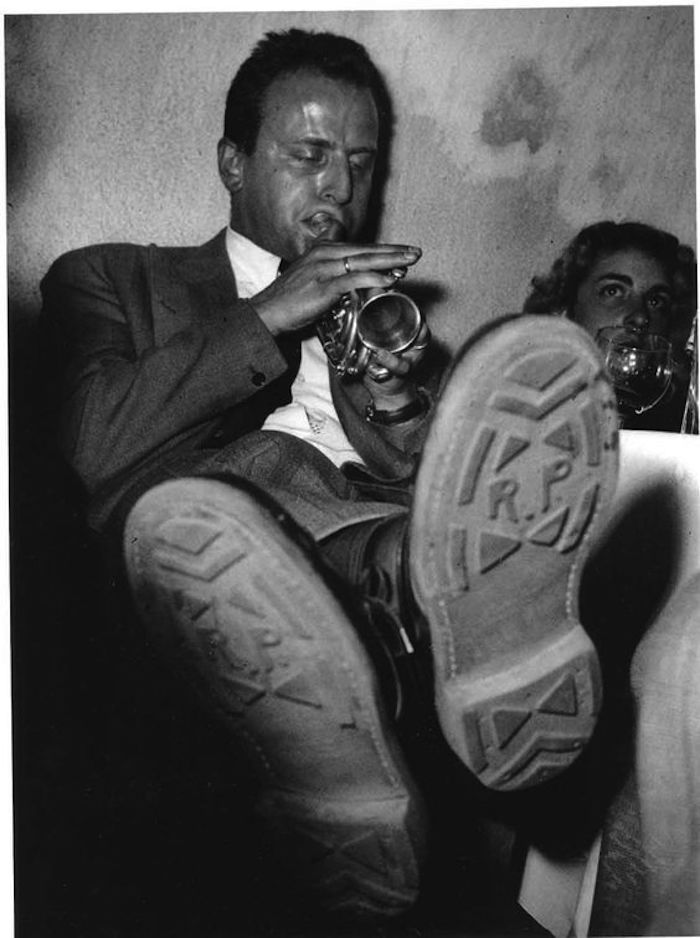

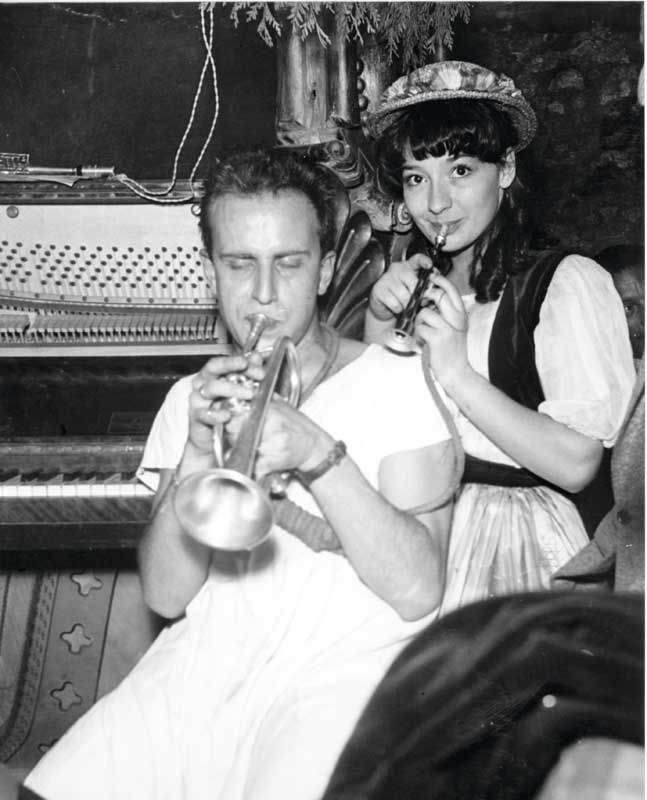

Known for his jazz music, racy literature, and love for American culture, Boris played his trumpet throughout Paris as a member and founder of various underground jazz clubs. Inspired by surrealism, he was famous for his word play and metaphors, making his works incredibly difficult to translate to English– which might explain why his name never came to be well-known across the Atlantic.

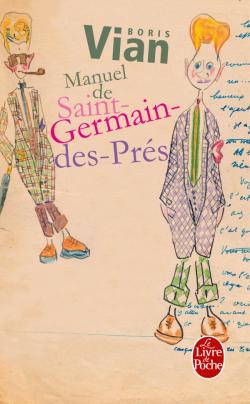

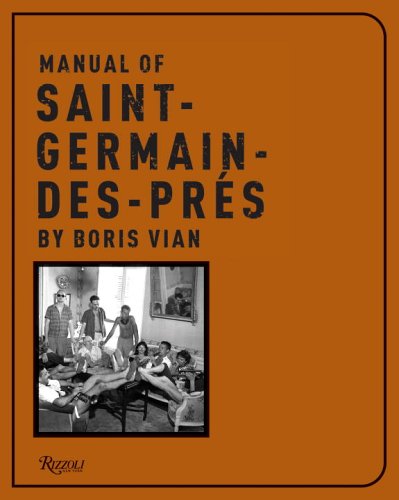

Like his music (and his parties), Vian’s literature is a strong reflection of his playful personality. Manuel de Saint-Germain-des-Prés is his satirical guide to the Left Bank arrondissement that was home to many of the partying intellectuals and counter culture movements of that time. He describes in detail the population of Saint-Germain, giving the name troglodyte, which scientifically translates to cave dweller, to those who frequented the clubs like Le Tabou.

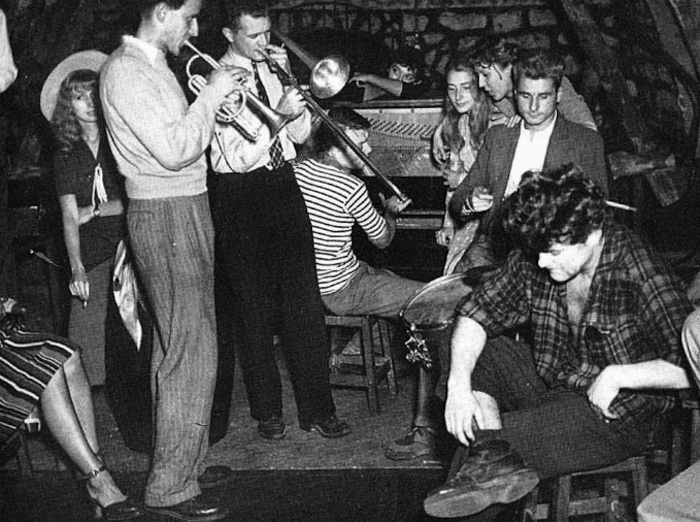

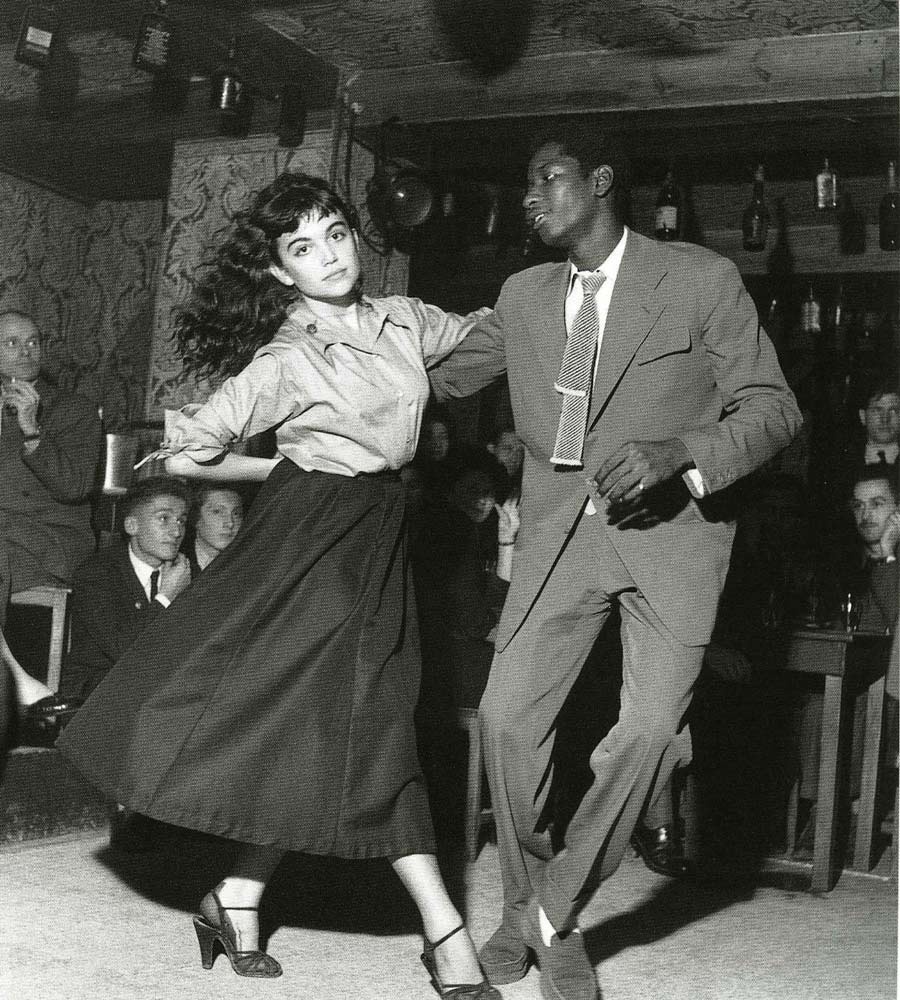

He paints a picture of Parisian youth with long hair, donned in garish clothing dancing the night away in the basement of a bar, going days without ingesting anything other than the cigarette smoke that constantly tainted the air. Boris had the unique ability to poke fun at the intellectuals, as well as the press who spoke poorly of them. The original manuscript of his guide which contained his own illustrations, was somehow lost and never found, but a versio that was eventually published provides an interesting perspective, particularly because of his willingness to critique the movements he himself was considered a part of.

Although Vian ran in the same social and intellectual circles as Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and is often grouped with the existentialist movement of the time, he was not a true existentialist. Rather than concerning himself with the meaning or lack of meaning of life, he was much more concerned with the act of living. His “joie de vivre” and philosophy of living likely stems from his health struggles which began at an early age.

As a child he was often confined to his family’s home, and at the age of 12 he developed a heart condition which led to his untimely death at the age of 39. His outlook not only led him to write some trippy literature, but made him the main feature of some of the craziest Parisian parties of the mid twentieth century.

Vian grew up in Ville-d’Avray, a suburb outside Paris, and it was here that he and his two brothers, Alain and Ninon, partied with hundreds of friends until sunrise in their backyard.

Upwards of 400 people regularly visited the villa’s jardin to dance the night away. Although only a teenager, his membership in the “Hot Club de France” and these elaborate legendary parties had already earned him a reputation in Paris.

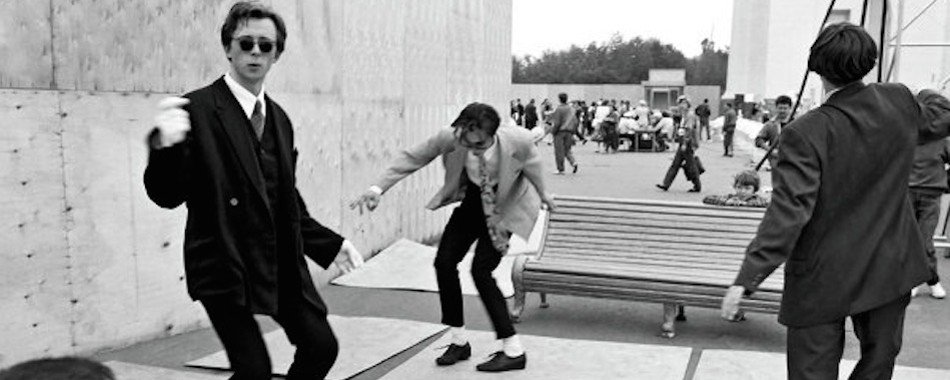

His fascination with American music and culture, which had been so actively oppressed by the Nazi occupation and the co-operating Vichy government, led to his association with the zazou movement. The zazou’s were a rising counter culture movement concentrated in Paris after the armistice with Germany during WWII, comprised mainly of young men and women who held a variety of political views, but were united through their opposition to the chief of the French Vichy regime (and their love of partying). Vian was not necessarily associated with the movement’s political views, but took part in its “l’esprit de la fête” (spirit of festivities) and shared the zazous’ bohemian taste in literature and music.

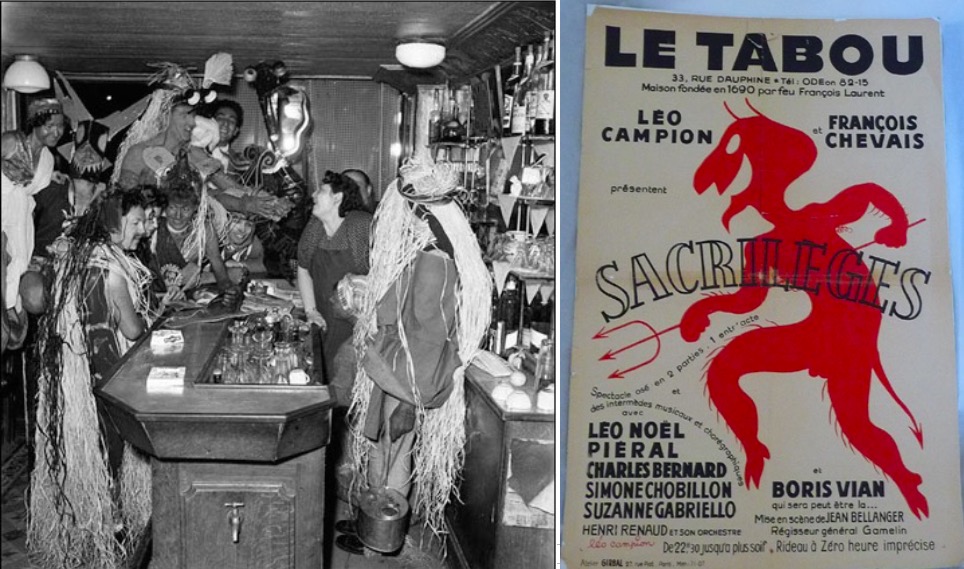

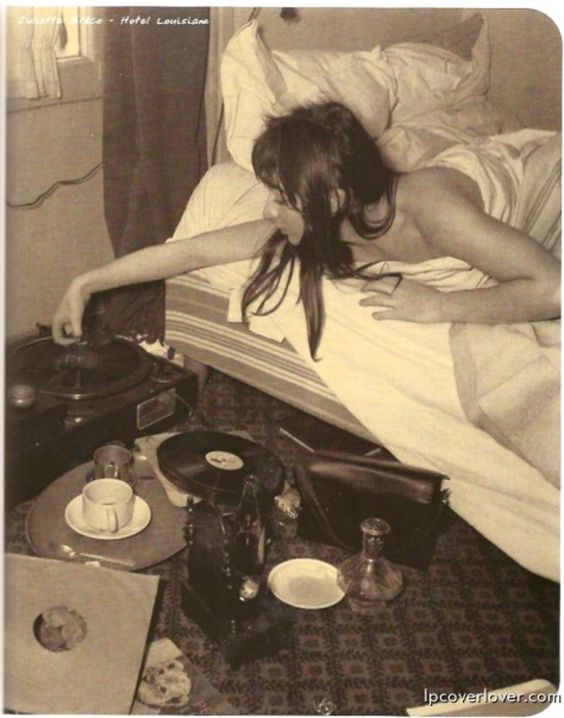

In 1947 Vian formed his own choir, “La Petite Chorale de Saint-Germain-des-Pieds,” and became closely involved with Le Tabou, a small jazz club in Saint-Germain-des-Prés which quickly came to be one of the hottest clubs in Paris. Legend says Vian wrote the club’s anthem “Ah, si j’avais un franc cinquante.” He wrote several other songs and met and partied with French singer and existentialist, Juliette Gréco, whom became a close friend.

Le Tabou was situated in the cellar of a small bar off of Rue Dauphine. After one climbed down a steep set of stairs they reached the underground room with no air conditioning or extract fans to dissipate the cigarette smoke; a cave just as Vian describes in Manuel de Saint-Germain-des-Prés. A stage sat at one end of the room, a bar and dancefloor on the other. Today the building that once housed Le Tabou is luxury Hôtel d’Aubusson, and the basement where Vian partied the night away is now a seminar room.

During the late 40s Vian started to associate himself with another jazz club, Le Club Saint-Germain-des-Prés. There he organised numerous concerts with big name jazz musicians like Duke Ellington, Charlie Parker, and Miles Davis, and personally guided the visiting musicians to the best after-parties in town.

Eventually he went on to create his own jazz hits like “C’est le be-bop” and “Le Déseteur,” and started writing cabaret shows.

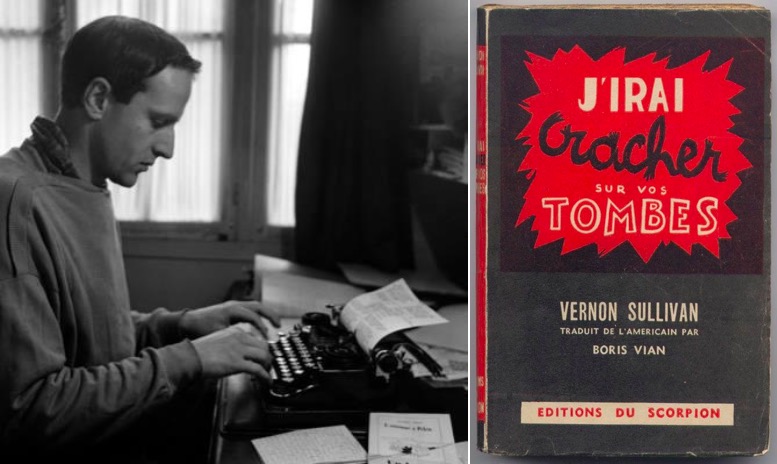

Although he never traveled to the U.S., his fascination with American culture continued throughout his life and was apparent in more than just his love of jazz music. In 1946, he had written J’irai Cracher sur vos Tombes (I will spit on your graves) under the pen name Vernon Sullivan, whom he claimed was a black American man, perhaps a darker type of practical joke.

Vian said he was merely the translator of the text and Sullivan’s work was not published in the U.S. because it was too honest about race relations of the time. His many friendships with black American musicians likely influenced the way he imagined the country. Eventually, after a law suit scandal on the grounds of the book being indecent, it was revealed that Vian was the true author.

While watching a film adaptation of J’irai Cracher sur vos Tombes, which he is said to have barely recognized as his novel, his heart gave out and he died. His close friend Juliette Gréco said:

Boris avait grand coeur. Un coeur trop gros. Cliniquement et humainement. C’était un tendre, très conscient de sa fragilité. De la fragilité de sa vie et du peu de temps qui lui serait accordé sur cette terre. Il savait parfaitement qu’il allait mourir.

“Boris had a big heart. A heart too big, literally and figuratively. He knew perfectly well he was going to die.”

When he was still young he predicted his own death at the age of 40, perhaps explaining his will power to accomplish so much in such a short amount of time. While the party ended early for Vian, his music, film, and literature have allowed it to go on for so many others.

Boris Vian’s Time Capsule Apartment in Montmartre

While most Parisians assume Boris Vian lived in Saint Germain, Vian actually didn’t have the means to live in the Left Bank and instead, resided at the foot of Montmartre in an apartment that used to be part of the backstage area of the Moulin Rouge.

The apartment has been remarkably preserved by the adopted daughter of his widow, who allows visits by appointment once a month. The Paris town hall visited the apartment and shared the experience online…

If you’re interested in visiting the apartment located on the charming cobblestone passage of Cité Véron, you can send an appointment request to contact@borisvian.org.

To listen to Boris play some jazz it’s here and to own his Manuel de Saint-Germain-des-Prés in English it’s here.